Andrew McGregor

September 9, 2010

While mercenaries have played an important role in the war on terrorism from the beginning, the use of private forces has until recently been associated with counter-terrorism efforts. However, since al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) began establishing a Saharan front, they have been compelled to hire local guides and suppliers, much like every other non-native interloper in the region. Many of the AQIM leaders in the Sahara are Arabs or Arabized Berbers from the coastal mountains of Algeria, nearly 2,000 miles from their current zone of operations in the desert near the Mali border.

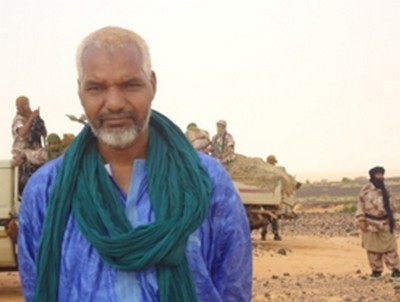

Omar al-Sahrawi (the nickname of Omar Sid Ahmed Ould Hamma) is one such employee of al-Qaeda participating in AQIM’s lucrative kidnapping operations without necessarily sharing the same ideology. In late August he was freed from captivity in Mauritania as part of a hostage exchange and ransom deal demanded by AQIM in return for the release of two Spanish captives.

Reports from Spain claim the hostages were released in exchange for between $4.8 million and $12.7 million as well as the release of al-Sahrawi (El Mundo [Madrid], August 23; ABC [Madrid], August 23). The two captives, Roque Pascual and Albert Vilalta, were kidnapped in Mauritania on the road from Nouakchott to the coastal town of Nouadhibou (formerly Port Étienne) in November 2009 (Afrique en Ligne, August 29). The men are employees of the Barcelona-based NGO Accio Solidaria. A third Spanish hostage taken at the same time, Alicia Gamez, was released by AQIM in March. It is believed a ransom was paid in this case as well.

In a telephone interview with a French reporter, al-Sahrawi declared, “I have nothing to do with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Me, I do business, and if you sell something to someone who is from AQIM, it does not mean that you are from AQIM. I am a businessman (AFP, August 24). In his homeland of Mali, security sources identified al-Sahrawi as a cigarette smuggler and transporter of illegal immigrants.

Al-Sahrawi had been sentenced by a Mauritanian court to 12 years of hard labor for his role in the abductions. Following his release and extradition to Mali, where the hostages were being held, al-Sahrawi was reported to have been present at the release of the hostages so AQIM could see if he was alive and in good health. Mauritanian TV footage showed al-Sahrawi joking with the hostages (AFP, August 25). On his return, Al-Sahrawi reportedly celebrated his release by declaring, “I have come back free to Mali” (Nouakchott-Info, August 26).

Referring to the failed Mauritanian-French effort to free a French hostage in July that resulted in the death of seven AQIM operatives and later the execution of the hostage, AQIM said the release of the Spanish hostages was a “lesson for the French secret services to take into consideration in the future” (al-Jazeera, August 24). Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero said the release marked a “day of celebration.” He made no mention of the ransom (Ennahar [Algiers], August 23).

Algiers is reported to be displeased with the ransom, some of which will likely be used to buy arms for further attacks within Algeria (Ennahar, August 25). Mauritania has also failed to garner AQIM’s good-will through the release; only two days later a would-be suicide bomber was killed by security forces as he tried to ram an explosives-laden truck into the Nema military barracks, 750 miles east of Nouackchott (al-Jazeera, August 25; AFP, August 25).

This article first appeared in the September 9, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor