Andrew McGregor

December 8, 2006

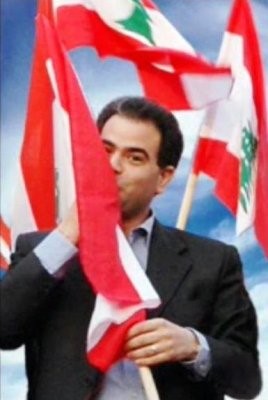

In the aftermath of the war with Israel, Hezbollah and its allies (the Shiite Amal Party and Christian leader General Michel Aoun) are struggling to depose the Lebanese government of Sunni Prime Minister Fouad Siniora and his March 14 coalition of anti-Syrian Sunni, Druze and Maronite politicians. On November 21, a team of assassins murdered Lebanese Minister of Industry Pierre Amine Gemayel in the streets of a northern Beirut suburb. The latest in a series of assassinations in Lebanon, the murder of the Maronite Christian leader seemed designed to inflame tensions as Lebanon’s political crisis threatens to plunge the country into civil war. It was the attempted assassination of Gemayel’s grandfather and namesake, Sheikh Pierre Gemayel, which sparked Lebanon’s long civil war in 1975.

Gemayel’s death by gunfire was highly unusual in Lebanon, where the preferred method of assassination is the car bomb. A Range Rover or similar vehicle rammed the car Gemayel was driving before a number of gunmen jumped out and began firing handguns equipped with silencers through the driver’s side window, killing Gemayel and a bodyguard. A second bodyguard was seriously wounded. Suspicion for the attack fell on Syria, whose alleged intention was to disrupt the Lebanese government to prevent an investigation by a UN international tribunal into the assassination of Lebanese politician Rafiq al-Hariri in 2005. Rafiq’s son, Sa’ad al-Hariri (leader of the al-Mustaqbal Party), quickly identified Syria as the culprit in the Gemayel killing (al-Mustaqbal, November 22). Later al-Hariri denounced Syria and Israel for wanting civil war in Lebanon and predicted that he and Druze leader Walid Jumblatt were the next targets for assassination (al-Ahram, November 28). Hezbollah’s military wing also claimed the killing was designed to instigate civil war in Lebanon (Moqawama.org, November 19).

Radical factions in Lebanon’s minority Sunni population saw the murder as part of an attempt by the Shiite Hezbollah organization to destroy Sunni political influence in Lebanon. A Sunni group known as the “Mujahideen in Lebanon” claimed that the murder was the work of five Hezbollah members. In a novel view of Lebanon’s political situation, the group accused the Shiites of engineering the insertion of UNIFIL to act as “a buffer” between Lebanese Sunnis and their Palestinian brethren, as well as acting in alliance with “the Crusaders” and Iranian-organized death squads to eliminate the Sunnis in Lebanon (al-Muhajirun, November 16). The group also threatened attacks on the predominantly Shiite southern suburb of Beirut, which it describes as a “pit of unbelief.” A leading Sunni sheikh, Sa’id Harmush, accused Hezbollah of abusing the Sunnis with “acts of robbery, slaughter, humiliation, and expulsion, much more than the Jews have done anywhere” (al-Mustaqbal, November 20). Other radical Sunni websites have urged the “liquidation” of Shiite leaders.

Hezbollah refutes claims that their opposition to the government is religiously inspired. According to Hezbollah Deputy Secretary General Na’im Qasim, “we do not demand the prime minister to resign because he is Sunni, but because he represents a political line which we believe makes the country adopt the U.S. position, something which the Sunnis themselves reject” (Asharq al-Awsat, November 22). Amal’s representative in Tehran also asserts that the dispute with the Sunnis over the government is “political and not religious” (Fars News Agency, November 22).

There are signs that al-Qaeda may attempt to exploit the political turmoil to create a violent rift between Lebanon’s Sunni and Shiite populations. A statement originating in the Nahr al-Barid Palestinian refugee camp declared that a group calling itself “Al-Qaeda in Lebanon” was prepared to “destroy this corrupt [Lebanese] government that takes its orders from the U.S. administration” (al-Nahar, November 13). The Mujahideen in Lebanon later claimed that the “al-Qaeda” statement was a fake. The leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, denounced Hezbollah leader Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah as a “charlatan agent of the anti-Christ” in a statement released by the Ministry of Information of the Islamic State of Iraq. Abu Hamza accuses Syrian President Bashar al-Assad of conspiring with Iran and Hezbollah to recreate “the old Persian Empire.”

Druze leader Walid Jumblatt accuses Syria of sending hundreds of al-Qaeda members to Lebanon’s Palestinian refugee camps, raising the possibility of Iraq-style sectarian violence and a continuing campaign of political assassinations (Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation, November 22). Reports from anti-Syrian factions claim that Syrian President al-Assad sent 200 terrorists to Lebanon from Fatah-Intifada, a Syrian-backed Palestinian group led by Abu Musa, a long-time dissident Palestinian leader. Working out of the camps, the Palestinians are alleged to be preparing the assassination of 36 Lebanese leaders (al-Mustaqbal, November 29; Naharnet/AFP, November 29).

The “Fighters for the Unity and Freedom of al-Sham” claimed responsibility for the assassination in a statement that described Gemayel as an agent working for foreign interests. The statement added that other “agents” would soon “be paid their due” (al-Nahar, November 22). The group (which many Lebanese see as a front for Syrian intelligence) claimed responsibility for the assassinations of anti-Syrian journalists Samir Kassir and Jibran al-Tueni in 2005 (al-Nahar, November 22). Both men were killed by car bombs rather than by gunmen.

Hezbollah and Amal leaders have hinted at a U.S. role in the Gemayel murder, making reference to a parcel addressed to the U.S. embassy in Lebanon that was intercepted by Lebanese Customs at Beirut Airport on February 3. The parcel contained silencers and other high-tech military equipment suitable for a sniper (al-Akhbar, February 3). Prior to Gemayel’s murder, Hezbollah leader Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah asked in a Lebanese TV interview, “Why does the U.S. Embassy need silencers? Is this meant to protect the U.S. Embassy or the Americans who are traveling or residing in Lebanon? Or is this meant to carry out assassinations, which the Americans are speaking about and expecting and which the Israelis are speaking about and expecting?” (al-Manar TV, October 31). U.S. officials denied any knowledge of the shipment, which was sent through the normal post rather than sealed diplomatic bags. The incident suggests premeditation on the part of some group that desired to implicate the United States in coming assassinations.

Unfortunately, Lebanon has become a showcase for covert activities, false-flag operations, provocations and disinformation campaigns. Attempting to pin responsibility for a specific operation is to wade deeply into the dark waters of international intrigue and manipulation. It is perhaps instructive to note that both sides in the struggle for dominance in Lebanon claim that the assassination of Pierre Gemayel benefited the opposing party.

It is difficult to see the advantage for Syria of killing a Lebanese cabinet minister from a U.S.-friendly faction just as Washington and London are moving toward opening a dialogue with Syria over Iraq and other regional issues. At the moment, the U.S. State Department and Pentagon are engaged in an internal struggle over Middle East policy. Syria’s ambassador to the United States pointed to “enemies” of Syria as the responsible parties for the assassination, suggesting their intention was to derail the Syrian-American rapprochement (CNN, November 22). Killing Gemayel would be to risk an opportunity to sweep the al-Hariri tribunal under the carpet and leverage Syria’s support on Iraq into concessions from Israel in the Golan Heights. It is also hard to see how al-Qaeda can successfully insert itself into the complicated Lebanese political structure. The notion of creating an Islamic regime exclusively from Lebanon’s minority Sunni community would be immediately dismissed by most Lebanese Sunnis.

Despite incredible internal and external pressures, Lebanon has not yet burst into sectarian violence. This indicates a maturing of the political process in Lebanon and a general reluctance to rejoin the horrors of civil war, although the crisis could tip over into violence at any moment.

This article first appeared in the December 8, 2006 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Focus