Andrew McGregor

July 21, 2011

In the wake of months of violent rioting by Burkina Faso’s military, police and civilians, the leaders of the West African nation’s military have announced the dismissal of 556 soldiers, 217 of whom will face charges ( L’Observateur Paalga [Ouagadougou], July 14; LeFaso.net, July 15). The move was announced at a press conference held by the Chief of General Staff of the Forces armées nationales (FAN), Brigadier General Naber Traoré and Brigadier General Diendéré Gilbert (FasoZine [Oougadougou], July 14).

General Nabéré Honoré Traoré (left) and General Gilbert Diendéré (right)

The Burkinabé armed forces have received extensive military assistance and training from the United States in recent years. Many officers have gone to the United States for additional training and the army is an important element in the U.S.-backed Trans-Sahara Counter Terrorism Partnership (TSCTP) (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, June 4, 2010).

President Blaise Compaoré has angered many in the country by announcing his intention to run for yet another term in 2015 in defiance of Article 37 of the Burkinabé constitution, which forbids a president from seeking more than two terms (L’Observateur Paalga [Ouagadougou], July 7). Compaoré came to power in a 1987 coup that saw the murder of his predecessor, the charismatic Captain Thomas Sankara, who had himself taken power in a 1983 Libyan supported coup organized by Compaoré. Compaoré initially ruled alongside two long term allies and fellow Marxists, Captain Henri Zongo and Major Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani, but in 1989 he abandoned Marxism and had both men arrested, quickly tried and executed on charges of trying to overthrow the government. Since then he has been re-elected four times in disputed elections that saw him win vast majorities. Observers have cited the “Burkinabé Paradox,” referring to the nation’s steady economic growth over the past five years and the complete lack of impact this has had on the country’s stifling poverty (Jeune Afrique, June 26). Wealth distribution remains largely limited to the small national elite tied to President Campaoré.

The military protests occurring across Burkina Faso typically consist of troops taking to the streets, firing randomly or into the air, pillaging shops and destroying property. Incidents of rape have also been reported. Their grievances usually consist of demands for better pay, an end to cronyism and political bias in promotions and an end to corruption in the officer corps, which the troops say fails to represent their interests (L’Observateur Paalga [Ouagadougou], July 7).

Civilian unrest began in the town of Koudougou (100 km west of Ouagadougou) on February 22, with demonstrators protesting the high cost of living and the culture of impunity and use of torture in the police that allegedly led to the death of a student in detention. The protests were received by tear gas and bullets and after two days of violence, six people were dead and the protests began to spread to other cities where police stations were burned and businesses looted (AFP, April 22). Strikes have spread to various economic sectors, including gold mines and the all-important cotton industry.

The military unrest began in late March when soldiers forcibly freed some colleagues from a prison in Fada N’Gourma who had been arrested for rape and other sex crimes (AFP, April 7).

On April 14 and 15, members of the Régiment de sécurité présidentielle (RSP – Presidential Guard) rioted until they received overdue wages and housing and food allowances they had been promised. During their rampage they looted the capital, stole cars and motorcycles and committed numerous acts of rape (AFP, April 20). The president fled the capital to his home town of Ziniaré. Army chief General Dominique Djindjéré, whose home was burned down by rioting RSP members, was replaced by Brigadier Honoré Naber Traoré on April 15 as part of sweeping changes in the military and police leadership (AFP, April 15). From Ouagadougou the unrest spread to the cities of Po, Tengkodogo and Kaya, where troops torched the home of a regimental commander and looted the home of the regional military chief (AFP, April 18).

On April 17, soldiers from the Po garrison near the Ghana border took over the town, looting, stealing vehicles and firing into the air in a three day rampage that also included a number of cases of rape (AFP, April 17).

Newly-appointed Prime Minister Luc Adolphe Tiao committed to subsidizing some essential goods and compensating victims of military and police mutinies in late April. Tiao, a journalist and former ambassador with no experience in governance, appointed a new cabinet in mid-April, but the 15 new ministers were all closely tied to the President (AFP, April 22). Campaoré himself became the new Defense Minister. All regional governors in Burkina Faso were later replaced on June 8, though three governors were simply transferred to different regions. Another three are active soldiers in the Burkinabé military (AFP, June 9).

On April 27 and 28, police officers in Ouagadougou defied a curfew and took to the streets, firing their weapons into the air to demand better pay and working conditions. Gunfire was also reported in Bobo Dioulasso (Burkina Faso’s second largest city), Dedougou, Gaoua and Banfora (Xinhua, April 28). Police agreed to end country-wide protests following two days of negotiations with the government. Large numbers of students gathered on April 20 to protest the police mutiny by setting fire to a police station, but were met with live fire from the police (AFP, April 29). Soon after the police mutinies, national police chief Rasmane Ouangraoua was sacked and replaced by the former police commissioner in Ouagadougou (AFP, May 5).

National Gendarmerie officers from Camp Paspanga in Ouagadougou spent the night of May 23 firing their weapons into the air to demand bonuses similar to those granted to the Presidential Guard. Just as they returned to barracks in the morning, students took to the streets as part of a nation-wide protest in support of striking professors. At the same time, protesters in Koudougou burned down the mayor’s house to protest the closure of 40 businesses that had failed to pay taxes (AFP, April 28).

The looting and random gunfire of riotous troops that persisted throughout the night of June 2 in Bobo Dioulasso was followed the next day by tradesmen and businessmen attacking the city hall, customs office and several other government buildings. The city’s mayor, Salia Sanou, did not find their reaction surprising: “They have had enough. I understand them. We promised to compensate them yesterday [for an earlier episode of military looting]. They kept their calm and now they get looted again” (AFP, June 2).

On June 3, the once-more loyal Presidential Guard teamed up with a unit of para-commandos and local police to put down the Bobo Dioulasso mutiny. Six mutineers were killed (as well as a teenage girl caught in the crossfire) and 57 arrested. The use of force was authorized after state intelligence informed the president the looting mutineers were being joined by former soldiers, men from other camps and even some who had nothing to do with the military (Jeune Afrique, June 26).

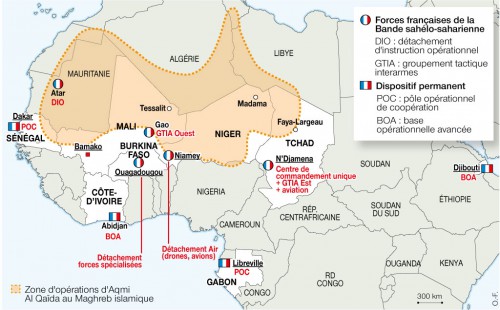

The breakdown in security and military discipline in Burkina Faso is especially worrisome in a region where elements of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb have been highly active in recent months.

This article was originally published in the July 21, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

French Mirage 2000 Jets during Operation Bayard (© Emmanuel Huberdeau)

French Mirage 2000 Jets during Operation Bayard (© Emmanuel Huberdeau) French Tigre HAD Attack Helicopter

French Tigre HAD Attack Helicopter