Andrew McGregor

January 25, 2017

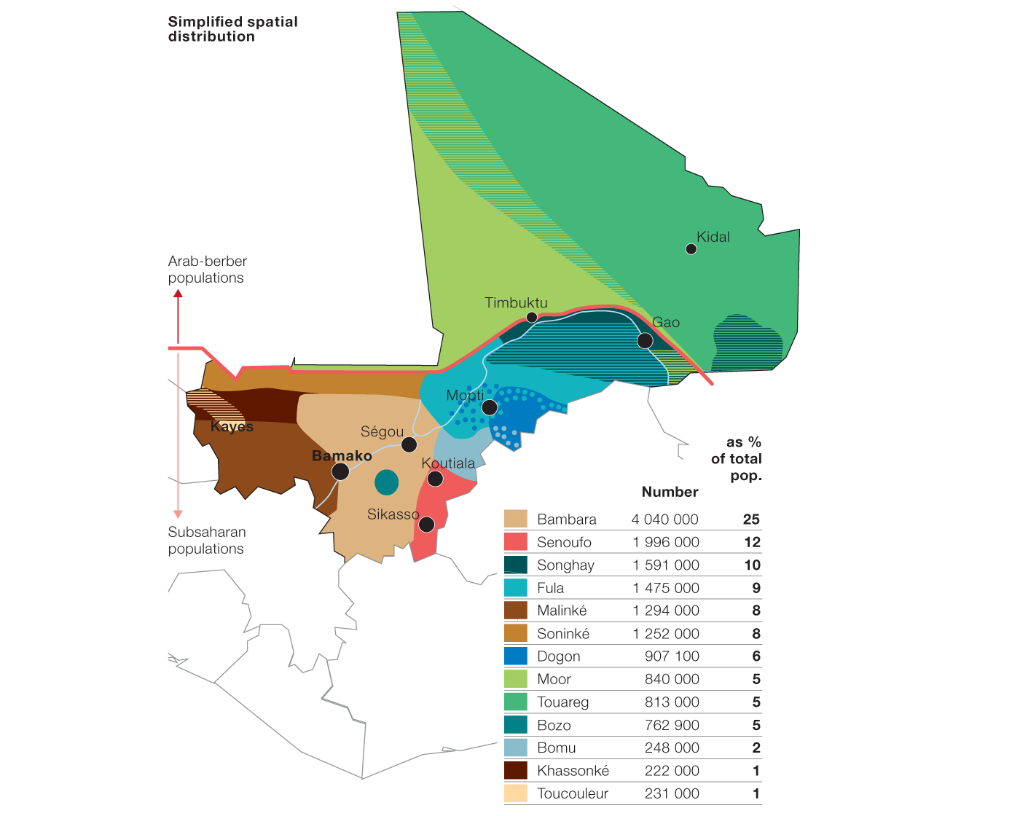

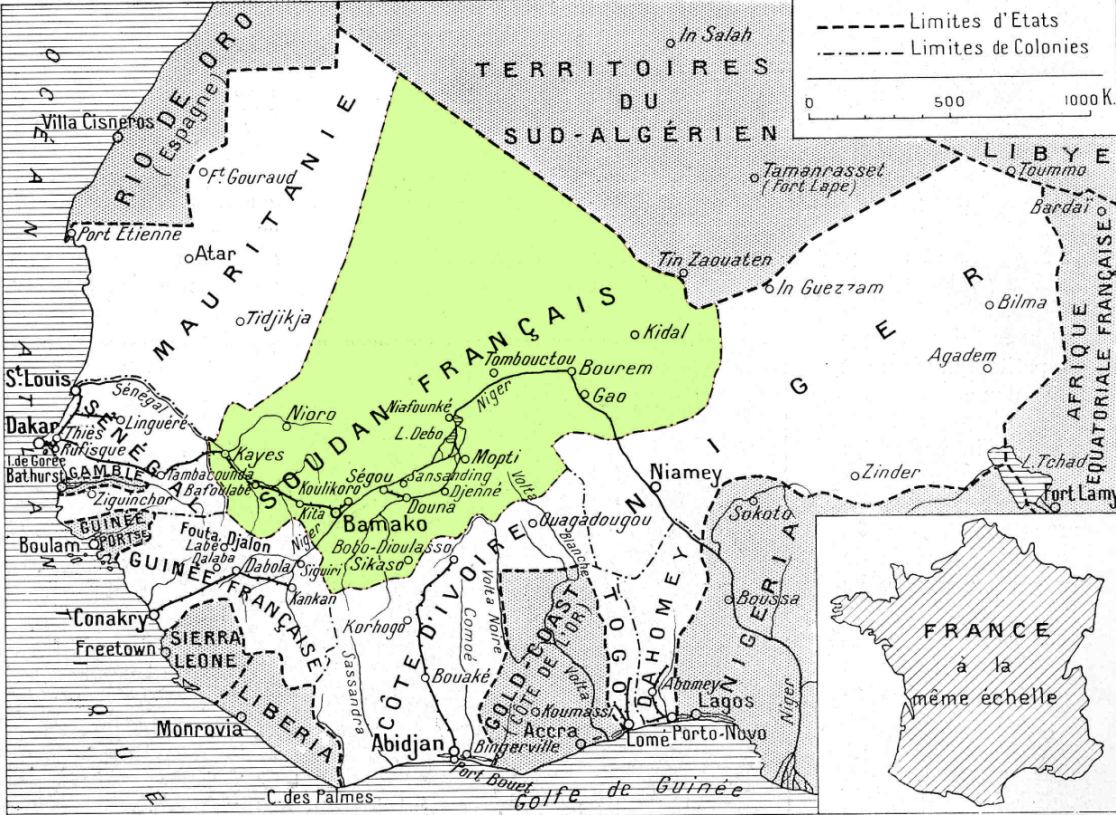

Achieving peace in northern Mali (known locally as Azawad) is complicated by the proliferation of armed groups in the region, each varying in purpose, ideology and ethnic composition. Personal and clan rivalries make cooperation exceedingly difficult even when political agendas match. MINUSMA peacekeepers and UN diplomats deplore this state of affairs, which prevents the establishment of a successful platform for negotiations, never mind implementing the 2015 Algiers Accords meant to bring peace to the region. [1] As in Darfur, many of the factional “splits” are intended to place the leaders of self-proclaimed armed movements in the queue for post-reconciliation appointments to government posts.

As a way of facilitating talks with a variety of rebel movements and loosely pro-government militias possible, most of the armed groups in northern Mali agreed in 2014 to join one of two coalitions – either the rebel/separatist Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA), or the pro-government Platforme coalition. Other armed groups devoted to jihad, such as-Qaeda, al-Murabitun and Ansar al-Din were deliberately excluded from the peace process and are not part of either coalition.

The June 20, 2015 Algiers Accord between the Malian government and the armed groups in the north was pushed through by an international community tired of the endless wrangling between northern Mali’s armed political movements. As a consequence, it is widely regarded in the north as an imposed agreement that does not address the often subtle and deep-rooted grievances that fuel the ongoing conflict. MINUSMA’s deployment, expensive in terms of both money and lives, is seen by the rebels as providing quiet support for Bamako’s efforts to retake the north through proxies such as GATIA, while ignoring the concerns of rebel groups.

Nonetheless, most of the armed groups in northern Mali can be brought together under one of five types: Pro-government militias (the Platforme); pro-independence or pro-federalism groups (the CMA); dissident CMA groups that have left the coalition; Salafi-Jihadist groups; and ethnically-oriented groups. Many of these groups break down further into brigades, or katiba-s.

Below is Jamestown’s guide to the non-state armed groups operating in northern Mail:

- The Platforme Coalition

Generally pro-government and/or favoring national unity, the coalition was formed in June 2014.

Coordination des mouvements et fronts patriotiques de résistance – Platforme (CMFPR I)

The Coordination of Patriotic Resistance Fronts and Movements was established on July 21, 2012 as a collection of self-defence movements from the Songhaï and Fulani/Peul communities in the Gao and Mopti regions. [2] The CMFPR split into pro and anti-government factions after leader Harouna Toureh rallied to the government and was dumped in January 2014 as spokesman by the main faction, which remained in the opposition CMA coalition as CMFPR II (22 Septembre [Bamako] January 30, 2014).

A Bamako-based lawyer, Toureh is currently defending former 2012 coup leader “General” Amadou Sanogo (Journal du Mali, December 2, 2016).

Groupe d’autodéfense des touareg Imghads et alliés (GATIA)

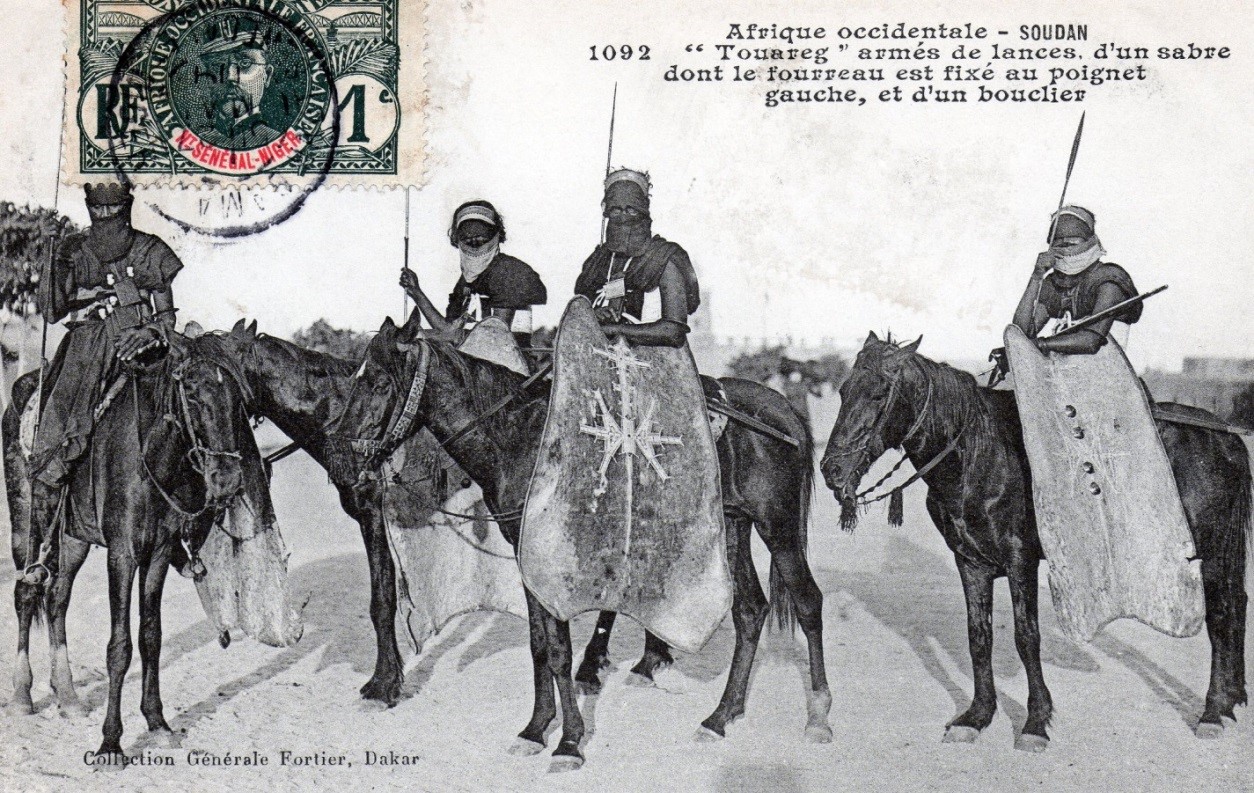

The Imghad and Allied Touareg Self Defence Movement was established on August 14, 2014. The movement is composed mostly of vassal Imghad Tuareg locked in a struggle with the “noble” Kel Ifoghas Tuareg of Kidal. Many of its members are veterans of the Malian and Libyan armies.

Although not a signatory to the Algiers Accord, GATIA is nonetheless the most powerful group in the Platforme coalition despite internal and international criticism that it is nothing more than an ethnic militia.

GATIA has been involved in constant clashes with CMA forces since its creation and continues to put military pressure on the rebel coalition. Though Fahad Ag Almahoud is secretary general, the movement’s real leader appears to be Brigadier General al-Hajj Ag Gamou, an example of the close ties this group has with the Malian Army.

Mouvement arabe de l’Azawad – Bamako (MAA-B)

The Arab Movement of Azawad – Bamako is a pro-Bamako faction of the MAA, led by Professor Ahmed Sidi Ould Mohamed and largely based in the Gao region with a military base at Inafarak, close to the Algerian border.

The MAA is dominated by members of the Lamhar clan, an Arab group whose recent prosperity and large new homes in Gao are attributed to their prominent role in moving drug shipments through the country’s north. Some are former members of the jihadist MUJAO group. The split in the MAA is interpreted by some as being directly related to a struggle for control of drug-trafficking routes through northern Mali.

The Mouvement pour la défense de la patrie (MDP)

The Movement for National Defense is a Fulani militia led by Hama Founé Diallo, a veteran of Charles Taylor’s forces in the Liberian Civil War and briefly a member of the rebel Mouvement National de Libération de L’Azawad (MNLA) in 2012.

The MDP joined the peace process in June 2016 by allying itself with the Platforme coalition (Le Républicain [Bamako], June 27, 2016; Aujourd’hui-Mali [Bamako], July 2, 2016). Diallo says he wants to teach the Fulani to use arms to defend themselves while steering them away from the attraction of jihad (Jeune Afrique, July 18, 2016). Other military leaders include Abdoulaye Houssei, Allaye Diallo, Oumar Diallo and Mamadou Traoré.

Mouvement pour le salut de l’Azawad (MSA)

Mohamed Ousmane Ag Mohamedoune (MaliWeb)

Mohamed Ousmane Ag Mohamedoune (MaliWeb)

The Movement for the Salvation of Azawad was founded by Moussa Ag Acharatoumane, former MNLA spokesman and the chief of the Daoussak Tuareg around Ménaka, along with Colonel Assalat Ag Habi, a Chamanamas Tuareg, also based near Ménaka. The two established the group after a September 2016 split in the MNLA and joined the Platforme on September 17, 2016, after being informed that the new movement could not remain inside the CMA (Journal du Mali, September 22, 2016; RFI, September 11, 2016; Le Canard déchaîné [Bamako], September 21, 2016).

Colonel Assalat Ag Habi (al-Jazeera)

Colonel Assalat Ag Habi (al-Jazeera)

Most members belong to the Daoussak or Chamanamas Tuareg (Le Repère [Bamako], January 3).

Centered on the Ménaka district of Gao region, MSA joined in a pact with the CJA, the CPA and the CMFPR II in October 2016, effectively creating an alternative CMA (L’indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], October 24, 2016).

2) Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA)

The Coordination of Azawad Movementscoalition was launched on June 9, 2014, but has lost several member groups since.

Haut conseil pour l’unité de l’Azawad (HCUA)

The High Council for the Unity of Azawad was formed in May 2013 from a merger of the Haut Conseil de l’Azawad (HCA) and the Mouvement islamique de l’Azawad (MIA). The HCUA is led by Algabass Ag Intallah, who also acts as the head of the CMA.

Another prominent member is Mohamed Ag Intallah, brother of Algabass and chieftain of the Ifoghas Tuareg of Kidal; deputy commander Shaykh Ag Aoussa was killed by a bomb in Kidal shortly after a meeting at a MINUSMA compound on October 9, 2016 (Journal du Mali, October 14, 2016).

The movement absorbed many former members of Ansar al-Din. The HCUA are suspected of remaining close to Ansar al-Din, despite rivalry between Iyad Ag Ghali and the Ag Intallah brothers over the leadership of the Ifoghas Tuareg. Last year, Mohamed, who may be trying to play both sides on issues like national unity or separatism, suggested engaging in “discussions with the Malian jihadists”, saying that, “in return they will help Mali get rid of jihadists from elsewhere” (MaliActu.net, March 13, 2016).

Mouvement arabe de l’Azawad – Dissident (MAA–D)

Sidi Ibrahim Ould Sidati (Journal du Mali)

Sidi Ibrahim Ould Sidati (Journal du Mali)

The Arab Movement of Azawad – Dissident is a breakaway group led by Sidi Ibrahim Ould Sidati. This faction of the MAA consists mainly of Bérabiche Arabs from the Timbuktu region, many of them former soldiers in the Malian army who deserted in 2012. The group rallied to the CMA in June 2014.

Other MAA-D leaders include suspected narco-traffickers Dina Ould Aya (or Daya) and Mohamed Ould Aweynat. The military chief of the dissenting MAA is Colonel Hussein Ould al-Moctar “Goulam,” a defector from the Malian army.

Mouvement national de libération de l’Azawad (MNLA)

The Azawad National Liberation Movement was established in October 2010 as a secular, separatist movement. It played a major role in the 2012 rebellion until it was sidelined by the more powerful Islamist faction led by Ansar al-Din.

Bilal Ag Chérif acts as the group’s secretary-general, while the military commander is Colonel Mohamed Ag Najim, an Idnan Tuareg and former officer in the Qaddafi-era Libyan army. Sub-sections of the Kel Adagh Tuareg (especially the Idnan and Taghat Mellit) are well represented in the movement.

Muhammad Ag Najim (Bamada.net)

Muhammad Ag Najim (Bamada.net)

The MNLA has suffered the most in an ongoing “assassination war” between CMA groups and armed Islamist groups. Despite the strong presence of Libyan and Malian Army veterans in its ranks, the MNLA has performed poorly on the battlefield.

3) CMA Dissident Groups

In the last year, a number of CMA groups have left the coalition, mostly because the alliance is perceived as promoting further violence rather than reconciliation. Some have referred to this alignment of dissident groups as “CMA-2.”

Coalition pour le peuple de l’Azawad (CPA)

The Coalition for the People of Azawad is led by Ibrahim Ag Mohamed Assaleh, the former head of external relations for the MNLA.

Ibrahim Ag Mohamed Assaleh (L’Afrique Adulte)

Ibrahim Ag Mohamed Assaleh (L’Afrique Adulte)

Established in March 2014 by 11 founding groups after a split in the MNLA, the group was initially weakened due to organizational rivalry between Ag Mohamed Assaleh and secretary general Shaykh Mohamed Ousmane Ag Mohamedoun (now MSA leader).

The CPA seeks federalism rather than independence. The movement is largely Tuareg, but claims membership from the Arab, Songhaï and Peul/Fulani communities.

Coordination des mouvements et fronts patriotiques de résistance II (CMFPR-II)

Ibrahim Abba Kantao (Journal du Mali)

The Coordination of Patriotic Resistance Fronts and Movements II is a rebel-aligned faction of the CMFPR led by Ibrahim Abba Kantao, who heads the Ganda Iso movement.

The group rallied to the CMA in June 2014 so as not to be left out of negotiations, with Kantao coming out against the partition of Mali (Malijet.com, July 15, 2014). In December 2014, Kantao took the unusual step of allying his movement to the Tuareg-dominated MNLA, vowing to “ally ourselves with the devil if it is necessary for the peace and salvation of our communities” (22 Septembre, December 29, 2014). The move shocked many CMFPR II members who view the Tuareg clans as rivals for resources and political authority.

A split occurred in the movement when clan disputes led to the formation of CMFPR III by Mahamane Alassane Maïga, but the circle was completed when Maïga led his movement back into CMFPR I in May 2015 (L’Indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], May 20, 2015).

4) Salafi-Jihadist Groups

Alliance nationale pour la sauvegarde de l’identité peule et la restauration de la justice (ANSIPRJ)

The National Alliance to Safeguard Peul Identity and Restore Justice was formed in June 2016. ANSPIRJ is led by Oumar al-Janah, who describes the group as a self-defense militia that aggressively defends the rights of Fulani/Peul herding communities in Mali, but is neither jihadist nor separatist in its ideology.

ANSPIRJ deputy leader Sidi Bakaye Cissé claims that Mali’s military treats all Fulani as jihadists: “We are far from being extremists, let alone puppets in the hands of armed movements” (Anadolu Agency, April 7, 2016). In reality, al-Janah’s movement is closely aligned with Ansar al-Din and claimed participation in a coordinated attack with that group on a Malian military base at Nampala on July 19, 2016 that killed 17 soldiers and left the base in flames (Mali Actu/AFP, July 19, 2016; Jeune Afrique/AFP, July 19, 2016).

ANSPIRJ’s Fulani military Amir, Mahmoud Barry (aka Abu Yehiya), was arrested near Nampala on July 27 (AFP, July 27, 2016).

Ansar al-Din

Led by long-time rebel and jihadist Iyad ag Ghali, a leading member of the Ifoghas Tuareg of Kidal and veteran of Muammar Qaddafi’s Islamic Legion. Ag Ghali is a noted military leader and sworn enemy of GATIA leader Brigadier al-Hajj Ag Gamou.

Ansar al-Din, with a mix of Tuareg, Arab and Fulani members, carries out regular attacks on French military installations or bases of the MINUSMA peacekeepers in northern Mali. The French believe Ag Ghali is “an enemy of peace” and remains Operation Barkhane’s number two target after Mokhar Belmokhtar (RFI, February 20, 2016; MaliActu.net, March 13, 2016).

Ansar al-Din’s weapons specialist, Haroun Sa’id (aka Abu Jamal), an ex-officer of the Malian Army, was killed in a French air raid in April 2014.

Ansar al-Din Sud (aka Katiba Khalid Ibn Walid)

Ansar al-Din Sud is sub-group formerly led by Souleymane Keïta, who was arrested in March 2016 by the Malian Secret Service. The group emerged in June 2015 with operations near the border with Côte d’Ivoire (Sikasso region) followed by further terrorist operations in central Mali.

Front de libération du Macina (FLM)

The Macina Liberation Front (aka Katiba Macina or Ansar al-Din Macina) is a largely Fulani jihadist movement led by Salafi preacher Hamadoun Koufa. Based in the Mopti region (central Mali), the group takes its name from a 19th century Fulani Islamic state. The Islamists have succeeded in recruiting young Fulanis by playing up the traditional Fulani leadership’s inability to defend its people from Tuareg attacks or cattle-rustling.

The movement allied itself with Ansar al-Din in May 2016, but split again earlier this year in the midst of diverging agendas and racial tensions (MaliActu.net, January 7, 2017, January 20, 2017). The FLM claimed responsibility for the July 19, 2016 attack on the Malian military barracks in Nampala that claimed the lives of 17 soldiers and wounded over 30 more (@Rimaah_01, on Twitter, July 19, 2016).

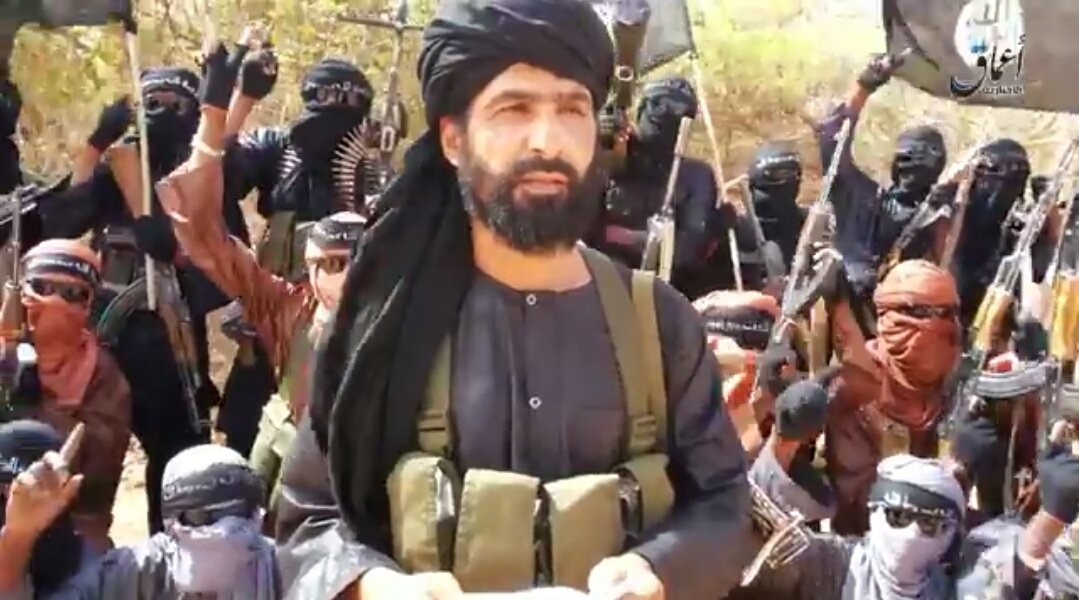

Islamic State – Sahara/Sahel:

The Islamic State (IS) has made steady inroads in northern Mali over the last two years and may benefit from the arrival of IS fighters and commanders fleeing defeat in Libya.

Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, a former al-Murabitun commander, publicly pledged allegiance to IS, together with his commanders, in May 2015, although IS only recognized the transfer of allegiance in October 2016. His defection to IS was publicly denounced by Mokhtar Belmokhtar (who said al-Sahrawi did not have any authority) and deplored by AQIM’s Saharan emir Yahya Abu al-Houmam (aka Djamel Okacha), who suggested ties with al-Sahrawi had not been irrevocably broken but nonetheless rejected the legitimacy of IS’ “so-called Caliphate” (al-Akhbar [Nouakchott], January 10, 2016).

Al-Sahrawi’s fighters now form the IS’ Saharan battalion. Recent reports suggest that Hamadoun Koufa of the FLM has been discussing collaboration in the creation of a new Fulani caliphate in the Sahel in what is seen as a betrayal of his sponsor, Ansar al-Din’s Iyad Ag Ghali (MaliActu.net, January 6, 2017; January 7, 2017).

The leader of the Fulani contingent of IS-Sahara is Nampala Ilassou Djibo. Mauritanian Hamada Ould Muhammad al-Kheirou (aka Abu Qum Qum), the former leader of MUJAO, also pledged allegiance to IS in 2015 (El-Khabar [Algiers] via BBC Monitoring, November 13, 2015).

Mouvement pour l’unité et jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest (MUJAO)

The Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa includes certain elements that appear to still be operating in Niger after the group’s hold on northern Mali was shattered in 2013 by France’s Operation Serval. Most of the movement joined al-Murabitun in that year, while other members drifted into various ethnic-based militias.

MUJAO’s military commander, Bérabiche Arab Omar Ould Hamaha, was killed by French Special Forces in March 2014. Commander Ahmed al-Tilemsi (aka Abd al-Rahman Ould Amar), a Lamhar Arab and known drug trafficker, was killed by French Special Forces in the Gao region of northern Mali on December 11, 2014.

Al-Murabitun

Al-Murabitun is an AQIM breakaway group that was formed in 2013 through a merger of MUJAO and the Katiba al-Mulathameen (“Veiled Brigade”) of Mokhtar Belmokhtar. [3]

The group claimed responsibility for the January 17 car-bomb attack in Gao that killed 77 members of the Malian Army and CMA groups, which it said was carried out by a Fulani recruit, Abd al-Hadi al-Fulani (al-Akhbar [Nouakchott), January 18). Fulani and Songhaï may now be found alongside the dominant Arab and Tuareg elements in the group.

Al-Murabitun’s foreign recruits are mostly from Algeria, Niger and Tunisia (RFI, May 14, 2014).

The group rejoined AQIM in December 2015.

Al-Qa’ida fi bilad al-Maghrib al-Islami (AQIM)

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb appears to have been reenergized by the re-absorption of the Mokhtar Belmokhtar-led al-Murabitun splinter group in December 2015. It has since carried out several attacks intended to re-affirm its presence in the Sahel region at a time when the movement’s role as the region’s preeminent Islamist militant group is being challenged by IS.

The emir of the Saharan branch of AQIM is Algerian Yahya Abu al-Houmam (aka Djamel Okacha), a jihadist since 1998. The group operates primarily in the Timbuktu region.

The unification with al-Murabitun was confirmed by AQIM leader Abu Musab Abd al-Wadud (aka Abd al-Malik Droukdel) on December 3, 2015, who announced the Murabitun members would now fight under the banner of the Katiba Murabitun of AQIM (AP, December 7, 2015; al-Khabar [Algiers], December 8 via BBC Monitoring). AQIM has four sub-commands of varying strength:

- Katiba al-Ansar: Formerly led by Hamada Ag Hama (aka Abd al-Krim al-Targui), an Ifoghas Tuareg and relative of Ansar al-Din leader Iyad ag Ghali, the brigade operated in Tessalit, in northeast Mali. Ag Hama was killed in a French operation in 2015. [4]

- Katiba al-Furqan: Based in the Timbuktu region, the brigade has been led by Mauritanian/Libyan Abd al-Rahman Talha al-Libi since September 2013. Al-Libi replaced Mauritanian Mohamed Lemine Ould al-Hassan (aka Abdallah al-Chinguitti), who was killed by French forces in early 2013 (Jeune Afrique, September 27, 2013). Al-Libi accuses France of “seeking to create a tribal conflict after the failure of its intervention in northern Mali” (aBamako.com via BBC Monitoring, December 2, 2015).

- Katiba Tarik Ibn Zaïd: The unit’s Algerian leader, Abd al-Hamid Abu Zaïd (aka Mohamed Ghdiri) was killed by French (or Chadian) forces in February 2013. In September that year, the command was transferred to Algerian Saïd Abu Moughati. [5]

- Katiba Yusuf ibn Tachfin: Formed in November 2012, this mostly Tuareg group is named for the Berber leader of the North African-Andalusian Almoravid Empire (c.1061-1106) and is led by Abd al-Krim al-Kidali (aka Sidan Ag Hitta), formerly of Katiba al-Ansar. Ag Hitta, a former sergeant-chef and deserter from the Malian National Guard, reportedly defected from AQIM and sought refuge from the MNLA during the battles of February 2013 (Le Figaro, March 3, 2013). He has since resumed jihadist activities but is regarded by many as little more than a bandit chief. The unit operates mostly in the mountainous Adrar Tigharghar region of Kidal.

5) Ethnically Oriented Groups

Congrès pour la Justice dans l’Azawad (CJA)

The Congress for Justice in Azawad is made up primarily of Tuareg, but has been weakened by leadership rivalries. It released its acting secretary general, Hama Ag Mahmoud, in December 2016. The group’s chairman is Azarack Ag Inaborchad. [6]

Abd al-Majid Ag Mohamed Ahmad (MaliWeb)

Abd al-Majid Ag Mohamed Ahmad (MaliWeb)

CJA allied with the MSA, the CPA and the CMFPR II in October 2016 (L’indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], October 24, 2016). The group has the support of Kel Antessar Tuareg leader Abd al-Majid Ag Mohamed Ahmad (aka Nasser), who is alleged to have supported the ouster of Ag Mahmoud (L’indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], January 18).

Now based in Mauritania, Ag Mahmoud retains the support of many CJA members who are unhappy with the change in leadership. The CJA operates mainly in the Kel Antessar regions of Timbuktu and Taoudeni.

Forces de libération du Nord du Mali (FLN)

The Liberation Forces of Northern Mali was created in 2012 from elements of the Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso (Fulani/Peul and Songhaï militias). CMFPR II leader Ibrahim Abba Kantao is an official with the group, which opposes the return of the Malian Army to northern Mali (L’Indicateur du renouveau [Bamako], April 21, 2015).

Mouvement populaire pour le salut de l’Azawad (MPSA)

The Popular Movement for the Salvation of Azawad is an Arab movement that is the result of a split in the MAA, with the dissidents who formed the MPSA claiming they wanted to remove themselves from the influence of AQIM (Anadolu Agency, August 31, 2014).

The group seeks self-determination for the north rather than independence but does not appear to be particularly influential.

Mouvement pour la Justice et la Liberté (MJL)

The Movement for Justice and Freedom was formed in September 2016. It is made up of Arab former members of the MAA in the Timbuktu region who announced they would no longer endorse the “unjustified war adventures” of the CMA coalition, in which the MAA was a main component.

The movement’s chairman is Sidi Mohamed Ould Mohamed, who has moved the MJL closer to the Platforme by seeking implementation of the Algiers Accords.

The MJL is centered on the Ber district of Timbuktu region (Le Repère [Bamako], January 3, 2017).

Notes

[1] Mission Multidimensionnelle Intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation au Maul (MINUSMA), the UN’s mission in Mali, is regarded by the CMA as being in league with the Platforme forces, though other sources accuse it of intervening against GATIA, the strongest unit in the Platforme coalition (Le Malien, August 1, 2016).

[2] The militias that banded together in 2012 under the CMFPR umbrella include: Ganda Iso (Sons of the Land), Ganda Koy (Lords of the Land), Alliance des communautés de la région de Tombouctou (ACRT), Front de libération des régions Nord du Mali (FLN), Cercle de réflexion et d’action (CRA) and the Force armée contre l’occupation (FACO). See also: Ibrahim Maïga, “Armed Groups in Mali: Beyond the Labels,” West Africa Report 17, Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, (June 2016). Available here.

[3] The Brigade also operated under the name Katiba al-Muaqiun Biddam – “Those Who Signed in Blood Brigade.”

[4] Ministère de la Défense, “Sahel: deux importants chefs terroristes mis hors de combat” (May 20, 2015). Available here.

[5] Alain Rodier, “Note d’actualité N°365: Al-Qaida au Maghreb Islamique à la Croisée des Chemins?” Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement, Paris, (August 17, 2014). Available here.

[6] Communiqué du Congres pour la Justice dans l’Azawad, Communiqué 005/CJA-BE/14-2017, (January 16). Available here.

This article first appeared in the January 25, 2017 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.