Andrew McGregor

Journal of Conflict Studies 23(2), Fall 2003, pp. 92-113

INTRODUCTION

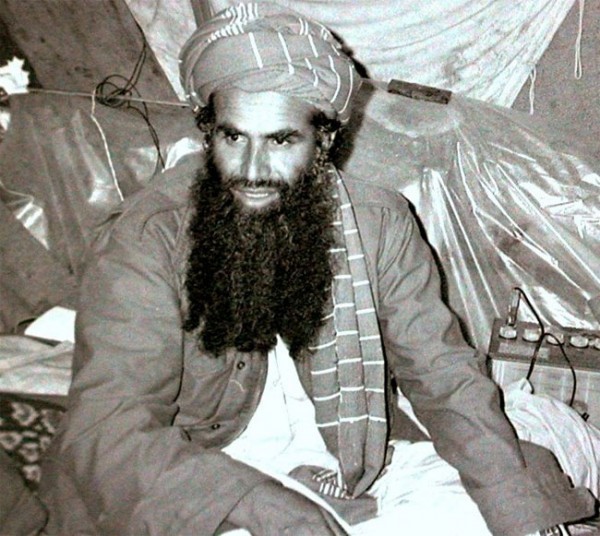

Palestinian-born Islamist Dr. ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam (1941-89) played a leading role in promoting and developing the modern Islamist concept of jihad. Little known in the West despite lengthy stays in the United States, ‘Azzam was responsible for internationalizing the Islamist struggle against secularism, socialism, and materialism. Though a scholar, ‘Azzam took his campaign to the front lines of Afghanistan during the Afghan-Soviet war, organizing the agency that would evolve into Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda. In many ways the life and work of ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam have already made him one of the most influential figures in modern times. As forms of jihad erupt from Algeria to the Philippines, it is important to understand the man whom so many mujahidin cite as their inspiration.

By tracing ‘Azzam’s thought through his most important influences, mediaeval scholar Ibn Taymiyah, Muslim Brother Sayyid Qutb, and Egyptian radical Muhammad Faraj, it is possible to see how the Shaykh’s ideology transformed radical Islam from a group of disparate movements defined by national borders into a potent (if scattered) force in the international arena.

“Jihad and the rifle alone; no negotiations, no conferences, and no dialogues”

This was the uncompromising answer of Shaykh ‘Abdullah Yusuf ‘Azzam to the encroachments of the Western and communist worlds into Islamic lands in the 1980s. Shaykh ‘Abdullah’s militant interpretation of the Islamic doctrine of jihad1 contributed to the success of the Afghan mujahidin, and has been an inspiration since his assassination in 1989 to a new generation of radical Islamists, including Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda organization and ‘Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Islamic jihad group in Egypt. While Islamists are frequently portrayed in the West as archconservatives who “want to return to the 7th century,” ‘Azzam saw himself and his confederates as revolutionaries, advancing a modern interpretation of Islam that could stand toe-to-toe with Western secularism or Eastern socialism. Part of ‘Azzam’s legacy is the internationalization of the Islamist movement and the authority he lent to the movement as a religious authority, something rare in militant Islamist groups.2 ‘Azzam’s recorded sermons and two influential books, Join the Caravan and The Defence of Muslim Lands, continue to receive wide circulation in Islamist circles.

Born in the West Bank village of Seelet al-Hartiyeh in Palestine in 1941, ‘Azzam’s philosophy was deeply influenced by the sight of Israeli tanks entering his village unopposed in 1967. After taking a BA in Islamic law in Damascus, ‘Azzam moved to Jordan to join the Palestinian resistance to the Israeli occupation. It did not take ‘Azzam long to discover he had little in common with the largely secular and socialist Palestine Liberation Organization. After Jordanian security forces brought a sudden and violent end to the unruly Palestinian movement within Jordan in 1970, ‘Azzam continued his studies on a scholarship at the al-Azhar University in Cairo (the preeminent school of Islamic studies), completing a PhD in the Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence in 1973.3 While in Egypt, ‘Azzam became close to the family and ideas of the late leader of the Muslim Brotherhood (al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin), Sayyid Qutb (1906-66).

Sayyid Qutb: Man Without Compromise

Qutb was an important ideologue in the modern Islamist movement, and his ideas so at odds with the Arab nationalism of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser that he was executed in 1966, accused (with several other Ikhwan) of plotting to overthrow the Egyptian government.4 Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood (assassinated 1949), had sought the Islamization of the Egyptian people before the creation of an Islamic state. Qutb went further, suggesting that “a revolutionary vanguard should first establish an Islamic state and then, from above, impose Islamization on Egyptian society and export Islamic revolutions throughout the Islamic world.”5 Qutb made the unique proposal that the existing Egyptian state could be overthrown on the grounds that it was “un-Islamic” and a promoter of modern jahiliya (ignorance of the truths of religion).

Qutb is regarded in many quarters as the father of uncompromising militant Islam. Yet, much of his work is inspired by Ibn Taymiyah (1263-1328), and was part of an increasingly militant approach to Islam that can be traced through the thought of Qutb’s Egyptian predecessor, Muhammad ‘Abduh (1849-1905) and ‘Abduh’s Libyan disciple Rashid Rida (1865-1935). ‘Abduh foresaw an inevitable triumph of Islam over other world religions, citing God’s promise in the Koran:

God has promised those of you who believe and do good works

To make them masters in the land,

as He has made their ancestors before them,

to strengthen the faith He chose for them,

and to change their fears to safety.

Let them worship Me and serve no other gods beside Me. (Koran 2, 55)

‘Abduh provided the following interpretation of this passage; “The Most High God has not yet succeeded in fulfilling his promise for us, but he has realized only part of it. It is destined that he will fulfill it by giving Islam mastery (siyada) over the whole world, including Europe, which is hostile to it.”6

Without fully realizing it, the Egyptian reformers were moving closer to the beliefs and practices of the Saudi Arabian Wahhabis. The Saudi Wahhabis originated in the seventeenth century as an Islamic reform movement dedicated to eradicating religious innovation, mysticism, pre-Islamic practices, saint-worship, and Shi’ism. Through an alliance formed between the al-Saud family and the Wahhabis, the latter are the dominant religious movement in the kingdom today. The royal family derives its legitimacy through Wahhabi approval. In Wahhabist theology, the Muslim community is continually revitalized and purified through the effort to “replace the customs of the jahiliyya by the Shari’a [Islamic law] and the ‘asabiyya [solidarity of the clan or tribe] of the tribes by the sense of Islamic solidarity, and thus to canalize the warlike energies of the beduin in a perpetual holy war.”7

Sayyid Qutb reinterpreted the concept of jahiliya, applying it to the expansionist non-Muslim world. This was a subtle reworking of the traditional Islamic division of the world into two spheres, dar al-Islam (the abode of Islam), and dar al-harb (the abode of conflict, i.e., an imperfect, non-Islamic social order). While a Muslim might ignore conditions in the dar al-harb, it was his duty to combat the threat posed by the jahiliya. To Qutb, jahiliya also meant the modern forces of “ignorance,” the secularism of both the Western capitalists and the Eastern communists. Soviet influence was strong in Egypt during the 1960s, but secular socialism had no more appeal to the Muslim Brothers than did secular materialism.

The jahiliya denoted, for Qutb, a polity legitimized by man-made criteria, such as the sovereignty of the people (rather than by divine grace), as well as a man-centred system of values and social mores (e.g., materialism, hedonism). Philosophical explanatory models — built on science alone with no place in their universe for God — are the apex, or perhaps nadir, of that jahiliya.8

Qutb’s own experience in the United States, as well as America’s perceived failure to support post-colonial independence movements led to Qutb’s harsh pronouncement on America’s moral legacy: “I fear that when the wheel of life has turned and the file on history is closed, America will not have contributed to anything.”9 Qutb was one of the first Muslim theorists to recognize early postwar American efforts to manipulate Islam in the interests of containing the spread of communism, a strategy that was to culminate in covert American support for the international mujahidin of ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam’s organization.

Hassan al-Banna had sought to convince Muslims that everything they needed to order society could be found in Islam: “We believe the rules and teachings of Islam to be comprehensive, to include the people’s affairs in the world and the hereafter . . . Islam is an ideology and a faith, a home and a nationality, a religion and a state, a spirit and work, a book and a sword.”10 By reminding Muslims of their duty to reform jahiliya, Qutb was able to externalize what many Islamic scholars had interpreted as the essentially defensive nature of the concept of jihad (a fight against religious oppression). Qutb objected to the idea that jihad was restricted to the defence of a territorially defined “homeland of Islam.” To Qutb, the “homeland of Islam” represented “Islamic beliefs, the Islamic way of life, and the Islamic community”:

The soil of the homeland has, in itself, no value or weight. From the Islamic point of view, the only value which the soil can achieve is because on that soil Allah’s authority is established and Allah’s guidance is followed; and thus it becomes a fortress for the belief, a place for its way of life to be entitled the ‘homeland of Islam,’ a center for the total freedom of man.11

S.M.A. Sayeed noted that, “Qutb took jihad into the widest possible connotation as the sole instrumentality to combat Jahiliyyah. It could issue in actual war on the physical plane and be extended to the efforts of creating a dynamic social organization which by virtue of its ideological strength could erode Jahiliyyah completely.”12 Nevertheless, some in the Brotherhood felt that Qutb had gone too far, and his influential work, Milestones on the Way (Ma’alim fi altariq), was denounced by Hassan al-Hodeibi, the spiritual leader of the Ikhwan. Al-Azhar condemned the book as heretical, the work of a “Kharajite.”13 This last work by Qutb was written from the prison hospital where the Islamist spent most of his sentence after enduring an initial year of torture and brutality in jail. Qutb’s opinions hardened as he witnessed the beatings and murders of his fellow incarcerated Islamists. He revised many of his earlier works and completely disowned others written in his secularist phase.14

Qutb also emphasized the importance of a return to ijtihad (the process of reasoning in regard to the interpretation of Islamic law), an activity that was declared “closed” to Sunni Muslims by Islamic scholars of the eleventh century. Again, Qutb was following Ibn Taymiyah’s lead in declaring that the process of ijtihad must never cease. This stance is now almost universal to modern Islamists, who call for the “reopening of the gates of ijtihad” while rejecting compromises with non-Islamic thought and ways.15

Qutb foresaw the emergence of a spiritual leader who would take the battle to the frontlines by citing the example of Ibn Taymiyah, a controversial Muslim theologian who lived in the Mamluk sultanate of Egypt and Syria. Qutb noted the pan-Islamic nature of Islam in Egypt in the Mamluk era, and its importance in defending Arab culture:

It is worthy to note that the Mamluks who repulsed the Tartars and drove them from the Islamic countries were not Arabs, but rather belonged to the same race as the Tartars. However, they stood fast against their kinsmen in defense of Islam because they themselves were Muslims, inspired by the Islamic ideal and fighting under the Islamic spiritual leadership of the great Muslim scholar (Imam) Ibn Taymiyah who lead the campaign of spiritual mobilization and who was in the forefront of the battle.16

During Ibn Taymiyah’s lifetime the Mamluk sultanate was constantly threatened by vast Mongol armies, which had inconveniently converted to Sunni Islam. This made it technically impossible for the Mamluk regime to call their war against the Mongols a jihad, with all the implicit ability to draw on the sultanate’s resources to a maximum. Ibn Taymiyah played an important part in legitimizing the religious aspect of the Mamluk war against the Mongols by challenging the Mongol’s understanding of Islam, pronouncing them un-Islamic in their knowledge and their practices. Declaring the Mongol leaders un-Islamic relieved the Mamluks of the injunction against fighting other Muslims, but but set a dangerous precedent that is at the heart of modern Islamist attacks on the legitimacy of national leaders in the Muslim world. Taymiyah’s inflexibility on religious matters would inspire both Qutb and ‘Azzam in their own challenges to the governing structures of the Islamic world.

Returning to the Law of God and His Apostle

Ibn Taymiyah has since been cited extensively by bin Laden as the inspiration for the jihad against corrupt regimes, such as the Saudi monarchy.17 In this case bin Laden follows the examples of two radical Egyptian Islamists, Shukri Mustafa and Muhammad ‘Abd al-Salam Faraj, both of whom drew heavily on Ibn Taymiyah and his modern popularizer, Sayyid Qutb.18 At his trial for the 1977 murder of a former minister of Religious Affairs, Shukri Mustafa gave lengthy explanations of Ibn Taymiyah’s thought (which did not prevent his conviction and execution by Egyptian authorities).

Muhammad ‘Abd al-Salam Faraj, the ideologue of the radical Egyptian Tanzim al-jihad group, was executed for his role in the 1981 assassination of President Sadat. Faraj wrote a defence of the actions of Tanzim al-jihad entitled Al-farida al-gha’iba (The Neglected Duty).19 Intended only for internal distribution among Islamists, Faraj’s work became highly influential in the Islamist network despite its many shortcomings as a work of Islamic scholarship. An examination of ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam’s works suggests that the jihad scholar was well acquainted with The Neglected Duty.

The title of Faraj’s document refers to the failure of “lax” Muslims to add jihad to the other five compulsory pillars of Islam: the profession of faith (shahada), prayer (salat), social taxation (zakat), fasting (saum), and pilgrimage (hajj). The concept behind the work appears to owe something to the writings of Mawlana Abul A’la Maududi (1903-79), an Indian-born journalist who became a leading Islamist theorist in post-independence Pakistan.20 Maududi asserted that, “the real objective of Islam is to remove the lordship of man over man and to establish the kingdom of God on Earth. To stake one’s life and everything else to achieve this purpose is called jihad, while Salat, Saum, Hajj and Zakat are all meant as a preparation for this task.”21

Using Ibn Taymiyah’s work and a very limited selection of Koranic verses, hadiths (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), and other sources as a justification for a jihad against an un-Islamic government, Faraj identified the leaders of the Egyptian state as apostates to Islam. For Faraj they were guilty of a greater crime than the Mongol rulers of Ibn Taymiyah’s day, who could at least be excused for their ignorance of Islam. Singling out the Egyptian government, Faraj quoted Ibn Taymiyah’s disciple, Ibn Kathir:

God disapproves of whosoever rebels against God’s laws, (laws) that are clear and precise and that contain everything which is good and that forbid everything that is bad . . .. Whosoever (rejects these laws in favour of other systems, i.e., the Mongols) is an infidel and he must be fought (yajib qitaluhu) until he returns to the Rule of God and His Apostle, and until he rules by no other law than God’s law.22

Faraj’s Islamic reformation was, however, directed solely at Egypt, relegating his revolution to a type of Islamic nationalism that many modern Islamists now reject in favour of wider aims. Faraj maintained that Muslims should strike first at “the enemy who is near”; in Faraj’s case, the allegedly apostate president of Egypt is implied.23 One of the most important elements of Faraj’s work is the definition of jihad as fard ayn (individually obligatory), a notion that echoes Maududi’s thought and would be returned to as a core point of ‘Azzam’s works. Faraj remarked:

With regard to the lands of Islam, the enemy lives right in the middle of them. The enemy even has got hold of the reins of power, for this enemy is (none other than) these rulers who have (illegally) seized the Leadership of the Muslims. Therefore, waging jihad against them is an individual duty, in addition to the fact that Islamic jihad today requires a drop of sweat from every Muslim.24

Al-farida al-gha’iba drew a major refutation in the form of a 1982 fatwa from Shaykh Jadd al-Haqq (mufti, or leading Islamic scholar, of Cairo’s al-Azhar University).25 The Shaykh’s unambiguous and decisive repudiation of Faraj’s work exposed the weakness in Faraj’s Islamic scholarship, typical of the fragile attempts of the non-scholars who dominate Islamist ranks to use Islamic discourse in justifying their actions. Al-Haqq deconstructed Faraj’s argument point by point, asserting the existence of “the greater jihad” (the spiritual struggle, repudiated by Faraj), and denying that “armed struggle” was the only possible interpretation of jihad, as suggested by Faraj. The mufti was especially opposed to the idea that Muslims had the right to declare other Muslims apostate (takfir) for the long list of reasons given by Faraj.26 In al-Haqq’s view, only the failure to acknowledge tawhid (the unity of God) could render a Muslim apostate. The evolution of Islamic society in Egypt had placed the responsibility for jihad upon the army of the state: “The character of jihad, so we must understand, has now changed radically, because the defence of country and religion is nowadays the duty of the regular army, and this army carries out the collective duty of jihad on behalf of all citizens.”27 In his analysis of Al-farida al-gha’iba, Mohammed Arkoun remarked upon how Ibn Taymiyah and the founders of the Islamic schools of jurisprudence were used by Faraj and other Islamists as authoritative and authentic sources on a level with the Koran itself: for the Islamists, “their information is incontestable and their interpretations infallible.”28

It is a common misperception in the West that Islamists are arch-conservatives in matters of law and religion; to the contrary, their belief in constant and even creative use of ijtihad (within certain restrictions) places them outside the Sunni mainstream and in opposition to not only the modernizing forces in Islam that emphasize the flexibility of the Shari’a, but also to the traditionalists who adhere to the importance of rigid observance of early interpretations of Islam.

“Never shall I leave the land of jihad“

Dr. ‘Azzam’s contribution to Islamic radicalism was to popularize the idea of a universal and international Islamic jihad, rather than the existing condition of each national Muslim group concentrating on a narrow area of concern related to their own circumstances (as in the jihad pursued by Muhammad ‘Abd al- Salam Faraj). It is easy to see how this conception grew from Qutb’s description of the jahiliya as a threat to Islamic life. In ‘Azzam’s words:

Jihad must not be abandoned until Allah alone is worshiped. Jihad continues until Allah’s Word is raised high. jihad until all the oppressed peoples are freed. Jihad to protect our dignity and restore our occupied lands. Jihad is the way of everlasting glory.29

Unlike many earlier jihad theorists who never fired a shot in anger, ‘Azzam provided an example to young Muslims by actively taking up jihad in Afghanistan, providing not only his considerable leadership and organizational skills, but by also serving on the front-line of combat. To ‘Azzam, Afghanis provided a model in resistance to the jahiliya: “the difference between the Afghan people and others is that the Afghans have refused disgrace in their religion, and have purchased their dignity with seas of blood and mountains of corpses and lost limbs. Other nations have submitted to colonization and disbelief from the first day.”30

‘Azzam’s long-term goal was the re-establishment of the Islamic Caliphate, a far more ambitious plan than was ever conceived by Qutb or the Muslim Brothers. Qutb’s concerns were first and foremost with the Islamic development of the Egyptian people.31 In 1924, the Ottoman Sultan (to whom the honour had devolved) was relieved of his role as Caliph of the Islamic world by Turkish arch-secularist Mustapha Kemal, bringing an end to any sort of central authority in Islam. Muslims, in ‘Azzam’s opinion, must not wait for the reestablishment of the Caliphate to pursue jihad; on the contrary, jihad is the “safest path” for the establishment of the universal leadership of the Caliphate.32 Faraj had already noted the downward spiral into which Muslims had fallen in the absence of the Caliphate:

After the disappearance of the Caliphate definitively in the year 1924, and the removal of the laws of Islam in their entirety, and their substitution by laws that were imposed by infidels, the situation (of the Muslims) became identical to the situation of the Mongols.33

‘Azzam did not refrain from admonishing those Muslims who failed to join the jihad in Afghanistan:

Through the course of this long period of time, the Afghans had expectations of their Muslim brethren in case their numbers became decreased, and also so that the Muslim brotherhood could be aroused in their depths. Yet, until now, the Muslims have not heeded their call. In the ears of the Muslims is a silence, rather than the cries of anguish, the screams of virgins, the wails of orphans and the sighs of old men. Many well-off people have deemed it sufficient to send some of the scraps from their tables and crumbs from their food.34

Like many modern Islamic reformers, ‘Azzam focused his interpretation of Islam on the concept of tawhid, the oneness of God. While the concept is universal in Islam, the reformers take it upon themselves to eliminate any threats to tawhid, especially the idea that there can be any intercession between man and God. Attempts to establish a mode of intercession are condemned as shirk (literally “association,” associating others with God in such a way as would threaten His absolute uniqueness). Such intercession may take the form of veneration of saints, shaykhs, imams, and even the Prophet Muhammad. Also condemned are pilgrimages to shrines or the tombs of saints, the wearing of amulets (usually inscribed with quotations from the Koran), and most aspects of Shi’ite religious observance. In doing so, the reformers find themselves opposed to the modes of worship followed by most Muslims in one form or another. The austerity and discipline of the Islamists therefore has little appeal to most stable and prosperous Muslim communities, but takes on a vital importance to communities in strife or perpetual economic disadvantage. In Chechnya, for example, radical Islamists have found fertile ground for their reform message, succeeding in having Shari’a declared state law following the defeat of Russian forces in 1996. Islamist discipline has proved a major factor in the success of some Chechen field commands in almost constant combat with Russian units.

In 1987 ‘Azzam presented a list of reasons why young Muslims should join the Afghan jihad:

- In order that the disbelievers do not dominate;

- The scarcity of men;

- Fear of Hell-fire;

- Fulfilling the duty of jihad, and responding to the call of the Lord;

- Following the footsteps of the Pious Predecessors;

- Establishing a solid foundation as a base for Islam;

- Protecting those who are oppressed in the land; and

- Hoping for martyrdom.35

‘Azzam traveled throughout Afghanistan on foot or by donkey, but was sorely disappointed by the lack of unity he found among mujahidin commanders. Despite this, ‘Azzam confirmed his commitment to the Afghan jihad; “Never shall I leave the Land of jihad, except in three circumstances. Either I shall be killed in Afghanistan, killed in Peshawar, or handcuffed and expelled from Pakistan.”36

Creation of the Mukhtab al-Khidmat

After completing his studies in Egypt, ‘Azzam returned to Palestine to fight the occupation, but was disgusted by the lax morals and inattention to religious observance of the largely secular and socialist Palestine Liberation Organization. The Saudis offered a teaching position at King ‘Abdul-‘Aziz University in Jeddah, and ‘Azzam remained there until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. It was at Jeddah that ‘Azzam first met a young and impressionable Osama bin Laden. While Cairo’s Al-Azhar University was essentially a conservative institution that preached cooperation between the state and the ulama, ‘Abdul-‘Aziz University was a hotbed of uncompromising approaches to the establishment and conduct of an Islamic state, bred in an atmosphere of puritanical Wahhabism.

In 1979, ‘Azzam determined it was time to put his principles into action and moved with his family to Islamabad in Pakistan. In Islamabad ‘Azzam would get to know the leaders of the anti-communist Afghan jihad while supporting himself as a lecturer at the International Islamic University. Before long ‘Azzam was involved in the jihad full-time, being one of the first Arabs to join the Afghan mujahidin.

‘Azzam moved to Peshawar with a plan to internationalize the jihad. In order to facilitate the movement of Islamist volunteers to the mujahidin struggle, ‘Azzam created the Mukhtab al-Khidmat (Services Centre) in 1984. This office also served as a means of channeling donations from Islamic charities and wealthy individuals in the Gulf States to support the mujahidin — sources of funding included the Saudi Red Crescent, Saudi intelligence services, the World Muslim League, and many individuals in the Saudi royal family.37 The establishment of this office was in large part the work of the Jordanian branch of the Muslim Brothers, many of whom were originally from Palestine. ‘Azzam began publishing an Arabic-language full color monthly journal from Peshawar called al-Jihad to publicize the Afghan jihad in the Arab world. At times it seems that ‘Azzam was occasionally overwhelmed by would-be mujahidin, arriving in Pakistan without any resources:

When we call people for jihad and explain to them its ordinance, it does not mean that we are in a position to take care of them, advise them, and look after their families. The concern of the scholars is to clarify the Islamic legal ruling. It is neither to bring people to jihad nor to borrow money from people to take care of the families of Mujahideen. When Ibn Taymiyyah or Al-‘Izz Ibn ‘Abd As-Salam explained the ruling concerning fighting against the Tartars [Mongols] they did not become obliged to equip the army.38

The Tragedy of al-Andalus

After founding the Mukhtab al-Khidmat, ‘Azzam became close to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leader of the Afghan Hizb-i Islami party, and a severe Islamic conservative who sought to eliminate traditional Islam within Afghanistan. Like most leading Islamists, Hekmatyar was a professional rather than an imam, and is referred to (in Central Asian fashion) as “Engineer Hekmatyar.” While receiving funding from Libya and Iran, Hekmatyar remained the leading recipient of American military aid via the increasingly Islamist Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Hekmatyar preferred to conserve his precious American arms and munitions in Pakistan while his political rivals, such as Tajik Islamist Burhanuddin Rabbani, exhausted themselves fighting the Soviets. The Saudi intelligence service under Prince Turki ibn Faisal avoided funding the Tajik Islamists, as it was feared that the Persian-speaking Tajiks might align themselves with Saudi Arabia’s Shi’ite rival, Iran.39 Both Hekmatyar’s and Rabbani’s political movements were called Hizb-i Islami.

Hekmatyar asserted the right to ijtihad, and promoted the strict Arabian Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence over the less rigid Hanafite school common in Afghanistan. Hekmatyar was brought into a coalition government as prime minister in 1992, but was highly suspicious of his partners, President Rabbani and Defence Minister Ahmad Shah Massoud (assassinated by al-Qaeda operatives in 2001). Eventually, Hekmatyar settled on demolishing Kabul with rockets from the heights he controlled nearby, killing thousands of Afghan civilians with weapons he had failed to use on the Soviets. During the anti-communist jihad of the 1980s, bin Laden, like ‘Azzam, was closely associated with Hekmatyar’s Hizb-i Islami party.40

‘Azzam also associated with Abdul Rabb Rasul Sayyaf, a Pashtun Afghan religious scholar resident in Peshawar who received Saudi funding to spread Saudi-style Wahhabism.41 Sayyaf formed a political party, Ittihad-i Islami- Barayi Azad-i Afghanistan (Islamic Union for the Liberation of Afghanistan), and adopted the Wahhabis’ rejection of Shi’ism, striving relentlessly to eliminate Afghanistan’s small Shi’ite community through violent means. Sayyaf, trained in Mecca rather than Cairo’s al-Azhar University — the preferred destination of Afghanistan’s religious scholars — was known to be hospitable to the Arab volunteers that passed through Peshawar on their way to Afghanistan.42 During this time ‘Azzam must also have come to know the Egyptians Muhammad ‘Atef and Dr. ‘Ayman al-Zawahiri, both of whom would eventually form part of the highest level of al-Qaeda’s leadership. The Shaykh was especially close to future al-Qaeda leader Khalid al-Shaykh Muhammad (recently captured in Pakistan) and his two brothers. ‘Azzam attributed a decisive role to the Arab volunteers in the fight for Afghanistan:

Indeed this small band of Arabs, whose number did not exceed a few hundred individuals, changed the tide of battle, from an Islamic battle of one country, to an Islamic World jihad movement, in which all races participated and all colours, languages and cultures met.43

‘Azzam saw unlimited potential for a united and militant approach to Islam: “If only the Muslims applied the command of their Lord, and executed the verdict of their Shari’a in going out to Palestine [for jihad] for a single week, Palestine would be permanently purified of the Jews.”44 Carefully going through works produced by the four schools of Islamic jurisprudence,45 ‘Azzam sought to establish that the pursuit of armed jihad was obligatory on all Muslims in such a way that could potentially draw the entire ummah (Islamic community) into conflict on behalf of Islam:

Ibn ‘Abidin, the Hanafi scholar says, “(jihad is) fard ‘ayn [individually obligatory] when the enemy has attacked any of the Islamic heartland, at which point it becomes fard ‘ayn on those close to the enemy . . .. As for those beyond them, at some distance from the enemy, it is fard kifayah [obligatory on a community scale] for them unless they are needed. The need arises when those close to the enemy fail to counter the enemy, or if they do not fail but are negligent and fail to perform jihad. In that case it becomes obligatory on those around them — fard ‘ayn, just like prayer and fasting, and they may not abandon it. (The circle of people on whom jihad is fard ‘ayn expands) until in this way, it becomes compulsory on the entire people of Islam, of the West and the East.46

‘Azzam often pointed to the precedent of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), where the Muslims were divided and failed in their jihad against their Christian enemies. In some cases Muslims made alliances with the Spanish Christians against their fellow Muslims. The result was the loss of the European jewel in the Muslim Empire. ‘Azzam’s analogy was clearly directed at the leaders of Muslim states like Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.47 Bin Laden specifically cited the “tragedy” of al-Andalus in his video statement of 7 October 2001: “Let the whole world know that we shall never accept that the tragedy of Andalusia would be repeated in Palestine. We cannot accept that Palestine will become Jewish.”48

The reference to al-Andalus proved so obscure in the West that some “expert” analysts thought it was a secret code disguised as gibberish. It was, of course, a reference to ‘Azzam’s works, little known in the West, but essential to someone like bin Laden, whose own scholarship in Islamic questions was deficient. The motif of al-Andalus has long found resonance in Arabic poetry as a spiritual and political metaphor, appropriate to the aims of ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam:

The poetic self that finds its meaning in the Andalusian movement . . . replicates Orientalist procedures in order to overthrow a Eurocentric, colonialist vision of history, and replace it with a vision of its own former colony, the utopian ideal of al-Andalu. It is not simply the case, however, that al-Andalus stands for a superior version of modern European civilization. It is, rather, an altogether higher reality, beyond the rule of fate and mortality for which Western imperialism stands. The turn toward this higher reality, the inward discovery of the image of al-Andalus, is therefore the foremost act in resisting the colonial order, and the foundation of political subjectivity.49

“Jihad means the obligation to fight”

In his seminal work on the necessity of armed jihad, Join the Caravan (Ilhaq bil-Qafilah), ‘Azzam described both the legal obligations and practical considerations surrounding the concept of jihad. The conditions upon which jihad becomes fard ‘ayn (individually obligatory) are outlined in an unambiguous fashion. jihad becomes fard ‘ayn when disbelievers enter the land of the Muslims. This condition thus makes jihad currently obligatory for every Muslim until the disbelievers are driven from Muslim lands. “It remains fard ‘ayn continuously until every piece of land that was once Islamic is regained.” It was acknowledged that this was a different situation than that which prevailed in the time of the Prophet’s immediate successors, when jihad was fard kifayah (a community obligation, not binding on individuals), since the Muslims were still embarking on new conquests.

‘Azzam stated that when jihad becomes individually obligatory there is no difference between it and the obligations of fasting and prayer. jihad means only combat with weapons and is a lifetime obligation that cannot be relieved through the mere donation of money.

The Shaykh also outlined the process that leads to jihad. First comes the hijrah, the emigration from non-Muslim lands, after the example of the Prophet’s hijrah from Mecca to Medina. Aperiod of preparation is followed by ribat (occupation of the front-lines of Islam), then combat. The Islamic community “remains sinful until the last piece of Islamic land is freed from the hands of the Disbelievers, nor are any absolved from sin other than the mujahidin.”50

The idea that jihad was fard ‘ayn quickly spread throughout the recruitment literature found in the Afghan refugee camps, which also extolled the virtues of the shahidin (martyrs). ‘Azzam was particularly hard on the widely held idea that there were two types of jihad. In most Sunni thought, jihad may consist of the greater jihad (al-jihad al-akbar — the struggle against evil within oneself), and the lesser jihad (al-jihad al-asgar — the physical fight against injustice). This belief in two types of jihad is based on a hadith that is not included in any authoritative collection of hadith, but which has nevertheless assumed enormous importance to many Sufi orders, who have devoted themselves to the pursuit of “the greater jihad.”51 Ibn Taymiya had challenged the Sufi orders for their deviations from Shari’a law, accusations that were taken up centuries later by the Wahhabis of Saudi Arabia and again by Egyptian Ikhwan founder Hassan al- Banna in the twentieth century.52 According to ‘Azzam:

The saying, ‘We have returned from the lesser jihad (battle) to the greater jihad (jihad of the soul),’ which people quote on the basis that it is a hadith, is in fact a false, fabricated hadith that has no basis. It is only a saying of Ibrahim Ibn Abi ‘Abalah, one of the Successors, and it contradicts textual evidence and reality.53

‘Azzam was well aware that one of Ibn Taymiyah’s disciples, Ibn al- Qayyim al-Jawziya (1292-1350), described the hadith as a complete fabrication in his work Kitab al-Manar. Faraj added that, “The only reason for inventing this tradition is to reduce the value of fighting with the sword, so as to distract the Muslims from fighting the infidels and the hypocrites.”54 ‘Azzam made his interpretation clear in a videotaped address to the al-Farook mosque in Brooklyn in 1988: “Whenever jihad is mentioned in the holy book, it means the obligation to fight. It does not mean to fight with the pen or to write books or articles in the press or to fight by holding lectures.”55

The disunity that continued to plague Afghanistan and other areas of conflict in the Islamic world was recognized by ‘Azzam as a major impediment for the Islamist program: “Muslims cannot be defeated by others. We Muslims are not defeated by our enemies, but instead, we are defeated by our own selves.”56 From 1985 to 1989, ‘Azzam spent much of his time traveling throughout the United States with his chief aide, Palestinian-born Shaykh Tamim al-Adnani, raising money, spreading the word of the new jihad through some 28 states. Support centers were established in New York, Detroit, Dearborn, Los Angeles, Tucson, and San Francisco. At one point half the readership of ‘Azzam’s magazine Al-jihad was in the United States.57

The Ink of Scholars and the Blood of Martyrs

‘Azzam turned against the Pakistanis in 1989, when it became apparent that manipulations by the ISI were causing heavy casualties among the mujahidin, particularly in the ISI-engineered siege of Jalalabad. The ISI was encouraging frontal assaults (of the type discredited in 1914) against reinforced communist positions supported by the Afghan air force. These tactics were a fatal break from the proven hit-and-run guerrilla attacks favored by the mujahidin.58 Some, like ‘Azzam, believed that with the imminent departure of the Russians from Afghanistan, the ISI was seeking to eliminate those factions of the resistance that were not under their control. During the summer of 1989, ‘Azzam attempted to mediate in the dispute between Ahmad Shah Massoud’s group and Hekmatyar, always returning to the need for unity among the mujahidin. Later that year a large quantity of explosives was placed beneath the minbar (pulpit) of the mosque in which ‘Azzam gave the Friday sermon. The explosives failed to detonate during the service (which would have killed hundreds), but ‘Azzam’s enemies were not deterred.

On 24 November 1989, a powerful bomb was planted along the narrow road that ‘Azzam habitually took to the mosque on Fridays. The blast ripped through ‘Azzam’s car, killing him, his two sons, and a young passenger. There were allegations that ‘Azzam’s assassination was undertaken by Burhanuddin Rabbani’s Hizb-i Islami, but to date no one has ever claimed responsibility for the attack. The list of suspects was long, and included the CIA, the ISI, the KGB, Israel’s Mossad, and Afghanistan’s own brutal security service, KHAD. An Israeli source cited rumours, “that have consistently linked Osama Bin Laden to ‘Azzam’s assassination.”59 Bin Laden is alleged to have become angered at ‘Azzam’s plan to ship arms to Hekmatyar’s enemy, Ahmad Massoud. Bin Laden took control of ‘Azzam’s organization, recreating it as al-Qaeda (“The Base”), a much more secretive group with narrower aims than al-Makhtab. With its almost exclusive focus on the removal of American troops from Saudi Arabia, al-Qaeda became more of an ideological throwback to earlier state-centred Islamist movements rather than the international movement envisioned by ‘Azzam.

CONCLUSION

Dr. ‘Azzam left a powerful legacy which his martyrdom only served to underline. The story of this leader and organizer of the international mujahidin in Afghanistan was circulated widely. Slight alterations reinforced ‘Azzam’s piety, such as the account that ‘Azzam’s companions in the fatal bombing were blown to pieces, while ‘Azzam’s body was discovered intact and unmarked, save for a small trickle of blood from his mouth. As ‘Azzam’s “Afghans” (as the international Arab volunteers came to be known) spread out to new fronts in the war against jahiliya, many cited him as their inspiration. Typical were the comments of Commander Abu ‘Abd al-‘Azziz, an Indian-born leader of the international mujahidin fighters in Bosnia in the mid-90s:

I was one of those who heard about jihad in Afghanistan when it started. I used to hear about it, but was hesitant about (the purity and intention) of this jihad. One of those who came to our land [Kashmir?] was sheikh Dr. Abdallah Azzam. I heard him rallying the youth to come forth and (join him) to go to Afghanistan. This was in 1984 — I think. I decided to go and check the matter for myself. This was the beginning (of my journey with) jihad.60

Cassette tapes of ‘Azzam’s speeches have circulated throughout the Middle East and Central Asia since his death. Until recently ‘Azzam’s thought has been propagated worldwide by a popular web-site, http://www.azzam.com (the site has suffered numerous disruptions since the events of 11 September 2001). In the West some radical preachers have taken up ‘Azzam’s call for hijrah as a first step in an international jihad. In Central Asia the Hizb ut-Tahrir movement has taken up the call for a revived Caliphate, to the considerable alarm of the ex-communist rulers of the region.

Even in death ‘Azzam’s ideas remain a perceived threat to the existing world order. ‘Azzam had (perhaps with some intuition) dealt with the role of the scholar as martyr in the service of the jihad:

The life of the Muslim Ummah (community) is solely dependent on the ink of its scholars and the blood of its martyrs. What is more beautiful than the writing of the Ummah‘s history with both the ink of a scholar and his blood, such that the map of Islamic history becomes coloured with two lines: one of them black, (that is what the scholar wrote with the ink of his pen); and the other red (and that is what the martyr wrote with his blood). And something more beautiful than this is when the blood is one and the pen is one, so that the hand of the scholar that expends the ink and moves the pen is the same as the hand that expends its blood and moves the Ummah. The extent to which the number of martyred scholars increases is the extent to which nations are delivered from their slumber, rescued from their decline and awoken from their sleep.61

One of the major projects of ‘Azzam’s Mukhtab al-Khidmat was the commissioning of the Mawsu’at al-jihad al-Aghani (The Encyclopedia of the Afghan jihad), a multi-volume Arabic-language work that describes everything from guerrilla tactics to bomb-making in simple terms with clear diagrams. The work appears to have been published in Peshawar sometime between 1994 and 1996. The first of four dedications was to ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, who did not live to see it completed:

A word of truth with a tear of allegiance,

To our beloved brother and reverend Sheikh ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam,

Who revived the spirit of jihad in the souls of the youth with the

word of God,

Who suffered harm from most people except from the faithful,

This work is dedicated first to Allah, then to you.

The encyclopedia mixed practical knowledge gained the hard way by Afghan mujahidin in their struggle with the Soviet Union with existing literature on terrorist methods. Much of the latter was American in origin: “CIA blackbooks — paramilitary training guides that the agency produced in the late 1950s and early 1960s — and other explosives literature available from Paladin Press, the militiaman’s favorite guide to weaponry and guerrilla tactics.”62 In 1995, Belgian police seized a copy of what appeared to be the entire encyclopedia on diskette, consisting of 8,000 pages of text. American troops and journalists found various parts of the work during the campaign in Afghanistan. The Encyclopedia of the Afghan jihad has become the On War by von Clausewitz of the Islamist fighters, explaining methods of maintaining what the West has come to call “asymmetrical warfare.”

While the encyclopedia is anonymous, it is known that Abu Bakr Aqidah, a one-legged Egyptian veteran of international jihad movements, wrote the volume on explosives. The mujahid spent two years as an instructor in one of ‘Azzam’s military training camps. Abu Bakr also completed a widely distributed manual on “Operational Tactics and Effectiveness,” based on the operations of the Chechen guerrillas. Abu Bakr was eventually killed in a daring raid on a Russian tank base in Daghestan in January 1997. The raid was led from Chechnya by the late Ibn al-Khattab (real name Samir bin-Salih bin-‘Abdallah al-Suwaylim), a Saudi-born veteran of Islamist guerrilla groups in Afghanistan and Tajikistan.63 Both men were typical of the ‘Azzam-inspired Arab volunteers who were willing to travel to the far-flung frontiers of Islam to give their lives for the cause of jihad.

It’s not surprising that Egypt and Saudi Arabia were the main sources for the 9/11 terrorists. These countries are, respectively, the homes of Egyptian jihad movements and Wahhabist theology, two trends that have grown closer on their extreme wings in recent decades. A convergence of the most extreme proponents of these lines of thought occurred when Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri brought his Islamic Jihad organization from Egypt to Afghanistan to join bin Laden’s al-Qaeda group in 1998. The result has been a self-justified ruthlessness in a war against the forces of the jahiliya. Al- Zawahiri, a physician rather than a religious scholar, appears to have combined the roles of ideologue and operations planner. The doctor also acts as a new mentor to the capable but impressionable bin Laden, who does not possess the religious training to provide justification for his own actions. According to bin Laden’s chosen biographer, “If Bin Laden had to give a speech at one of these rallies where people shout Osama’s name and call for jihad, the crowd would be sorely disappointed.”64

‘Azzam’s charismatic presence and powerful oratory are completely absent from the al-Qaeda of bin Laden and al-Zawahiri. Both men, however, see themselves as leaders of a mandatory jihad against the forces of the modern jahiliya. They have rigidly applied ‘Azzam’s belief that obedience to a leader is a necessity in jihad, “and thus a person must condition himself to invariably obey the leader.”65 al-Qaeda‘s leaders are believers in ‘Azzam’s chilling and inflexible approach to historical change:

History does not write its lines except with blood. Glory does not build its lofty edifice except with skulls; honour and respect cannot be established except on a foundation of cripples and corpses. Empires, distinguished peoples, states and societies cannot be established except with examples. Indeed those who think that they can change reality, or change societies, without blood, sacrifices and invalids, without pure, innocent souls, then they do not understand the essence of this Din (religion).66

Endnotes

- There is an extensive literature on the concept of jihad. Useful works in English include R. Peters, Islam and Colonialism: The Doctrine of jihad in Modern History (The Hague: Mouton De Gruyter, 1979); S.A. Schleifer, “Understanding jihad: Definition and Methodology,” Islamic Quarterly 27, no. 3 (1983), pp. 117-32; and “jihad and the traditional Islamic consciousness,” Islamic Quarterly 27, no.4 (1983), pp. 173-203.

- Radical Islamist movements are rarely led by religious scholars, consisting for the most part of professionals, such as engineers and doctors. “An important implication of the Islamist power model is that it excludes the ‘ulama (religious scholars) as an intermediary authority (between God and the head-of-state). The argument here is that the basic principles of Islam have been rendered unalterable and that no authority, whether secular or religious, is in a position to subvert or circumvent them — in other words, the prerogatives of the religious authorities in Islam are very limited.” Asta Olesen, Islam and Politics in Afghanistan (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1995), p. 242.

- While al-Azhar’s senior faculty is closely watched by the Egyptian government, the student body of Egyptian and international students has frequently become involved in extreme Islamist politics. Steven Barraclough, “Al-Azhar: Between the government and the Islamists,” Middle East Journal 52, no.2 (Spring 1998), p. 239.

- Qutb and other members of the Ikhwan provided vital assistance to the “Free Officers Movement” in their revolution, expecting to play a major (if not definitive) role in the new government. Nasser betrayed the brothers, offering Qutb only a minor position as deputy minister of Education. See Helmi el-Namnam, Sayyid Qutb wa Thawrat Yulyou (Sayyid Qutb and the July Revolution) (Cairo: Meret for Publication and Information, 1999). After his execution Qutb was buried in a hidden and unmarked grave by the Egyptian government.

- Mir Zohair Husain, Global Islamic Politics (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), p. 15. The idea of an Islamic revolutionary vanguard was also developed by Mawlana Abul A’la Maududi in his work, Process of Islamic Revolution (Lahore: 1955), pp. 37-55.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, Tafsir al-Qur’an al-hakim (Cairo: 1346-54AH (1927-35)), I, p. 170. Muhammad ‘Abduh’s lectures and writings were collected and added to by Rashid Rida, and published as a great multi-volume commentary (never finished) on the Koran, popularly called Tasfir al-Manar, after the name of Rida’s journal.

- Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798-1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p. 38. Jahiliya may also refer to “the age of ignorance,” i.e., pre- Islamic times.

- Emmanuel Sivan, “Ibn Taymiyya: Father of the Islamic Revolution: Medieval Theology and Modern Politics,” Encounter 60, no. 5 (May 1983), p. 45. Qutb had been sent on a study mission to the United States in 1948-50 that was expected to moderate his opposition to the West. Instead, it confirmed Qutb’s vision of the United States as the embodiment of the modern jahiliya, a nation lacking a moral conscience (damir). See John Calvert, “‘The World is an undutiful boy!’: Sayyid Qutb’s American Experience,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 11, no. 1 (2000), pp. 87-103.

- Sayyid Qutb, “Amrika allati ra’ayt fi mizan al-insaniyya,” Al-Risala, no. 957 (1951), pp. 1245-6, cited in Calvert, “The World is an undutiful boy,” p. 100.

- Quoted in Abd al-Moneir Said Aly and Manfred W. Wenner, “Modern Islamic reform movements: The Muslim Brotherhood in contemporary Egypt,” Middle East Journal 36, no. 3 (Summer 1982), p. 340. The slogan of the Muslim Brothers was ‘Al-islam din wa’dawlah’ (Islam is a religion and a state).

- Sayyid Qutb, “Paving the Way,” 24 November 2001, Internet source: http://www.islam.org.au/articles/23/qutb.htm, taken from Nida’ul Islam, no. 23 (April-May, 1998).

- S.M.A. Sayeed, The Myth of Authenticity (A Study in Islamic Fundamentalism) (Karachi: Royal Book Co., 1995), pp. 151-2.

- Gilles Kepel, Muslim Extremism in Egypt: The Prophet and the Pharaoh (London: Saqi Books, 1985), p. 101. The Kharajites (Ar.: khawarij, ‘outsiders’) were a seventh century sectarian movement that favoured the establishment of a theocracy in preference to violent struggles for leadership in the Islamic community. Under the slogan “No government but God’s,” they were defeated on the battlefield but adopted a campaign of political assassinations, on the grounds that the ruling Ummayad dynasty were not true Muslims.

- Useful works on Qutb include Yvonne Haddad, “Sayyid Qutb: Ideologue of Islamic Revival,” in John Esposito, ed., Voices of Resurgent Islam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983); Gilles Kepel, Muslim Extremism in Egypt: The Prophet and the Pharaoh (London: Saqi Books, 1985); Olivier Carré, Mystique et politique: lecture révolutionnaire du Coran par Sayyid Qutb, frère musulman radical (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1984); Ahmad Mousalli, Radical Islamic Fundamentalism: The Ideological and Political Discourse of Sayyid Qutb (Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1992). Qutb’s work became known in Afghanistan after Mawlawi Younos Khales translated and published Islam wa edalat-i ijtemai (Islam and Social Justice) in 1960. Ex-Afghan president and leader of the Jami’at al-islami party Burhanuddin Rabbani translated several of Qutb’s works while studying at al-Azhar University in Cairo (1966-68). The Jami’ati Islami party journal Misaq-i Khun would later publish many translations of works by the Egyptian Muslim Brothers.

- Qutb’s advocacy of violent jihad may be contrasted to the “intellectual jihad” pursued by his Indian-born contemporary, Fazlur Rahman (1919-88), who also sought to reopen “the gates of ijtihad.” “The intellectual endeavour, or jihad, including the intellectual elements of both the moments — past and present — is technically called ijtihad, which means ‘the effort to understand the meaning of a relevant text or precedent in the past, containing a rule, and to alter that rule by extending or restricting or otherwise modifying it in such a manner that a new situation can be subsumed under it by a new solution.'” Fazlur Rahman, Islam and Modernity: Transformation of an Intellectual Tradition (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1982), pp. 6-7. Rahman was a lecturer at McGill University’s Institute of Islamic Studies in the 1950s.

- Sayyid Qutb, Islam: The Religion of the Future (Al-mustaqbal li-hadha al-din), (Delhi: Markazi Maktaba Islami, Delhi, 1974) (Written in 1960).

- Osama bin Laden, I’lan al-jihad ‘ala al-Amrikiyyin al-Muhtalin li Bilad al-Haramayn (Declaration of War against the Americans Who Occupy the Land of the Two Mosques) (Afghanistan, 23 August 1996).

- The 1970s saw a proliferation of radical Islamist groups in Egypt, inspired by the works of Sayyid Qutb, Ibn Taymiyah, and Indian/Pakistani ideologue Mawlana Abul A’la Maududi (1903-79). The radicals were dismayed by the defeat of the Arab allies in the 1967 war with Israel (which also marked the death of secular Arab nationalism as an inspirational political movement). The new Islamist groups included Munazzamat al-Tahrir al-Islami (Islamic Liberation Organization), Jama’at al-Muslimin (Association of Muslims, often better known as Takfir wa’l Hijrah [Denouncement and Holy Flight]), and Munazzamat al-jihad (Holy Struggle Organization). These groups were eventually joined by the powerful al-Gama’a Islamiyya (Islamic Group), responsible for the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center.

- A complete translation of this work can be found in J.G. Jansen, The Creed of Sadat’s Assassins and Islamic Resurgence in the Middle East (New York: MacMillan, 1986), pp. 159-230.

- Maududi was greatly admired by Qutb, who appears to have been influenced by Maududi’s conception of Islam as a revolutionary force. As Maududi expressed it in 1926, “Islam is a revolutionary ideology and program which seeks to alter the social order of the whole world and rebuild it in conformity with its tenets and ideals,” A.A. Maududi, jihad in Islam (Beirut: Holy Koran Publishing House, 1980), p. 5.

- A.A. Maududi, Fundamentals of Islam (Delhi: 1978), p. 243

- Ibn Kathir, Tafsir (Cairo: n.d.), vol. 2, p. 67.

- Muhammad ‘Abd al-Salam Faraj, Al-farida al-gha’iba, in Jansen, The Creed of Sadat’s Assassins, pp. 192-93, §68.

- Ibid., p. 200, §87.

- Jadd al-Haqq ‘Ali Jadd al-Haqq, et. al., Al-fatawa al-islamiyah 10/31 (Cairo: 1983), p. 3733. Al-Haqq was Shaykh of al-Azhar from 1982 until his death in 1996. Al-Haqq’s condemnation of Egyptian Islamist groups did not include the Muslim Brothers, who ceased to advocate violence in the transition to a fully Islamic society following their failed assassination attempt on Nasser.

- “The debate about takfir, that is, declaring a Muslim to be an unbeliever, is the watershed between moderate and radical Islamism. If takfir is religiously lawful, then violence and revolution are religious duties. For radical Islamists, one should kill a ruler who claims to be a Muslim but does not rule according to Islam.” Olivier Roy, Afghanistan: From Holy War to Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1995), p. 37.

- Jadd al-Haqq, et. al., Al-Fatawa al-islamiyah, p. 3733.

- Mohammed Arkoun, “The Topicality of the Problem of the Person in Islamic Thought,” International Social Science Journal no. 117 (August 1988), p. 417. Many radical Islamists reject the authority of the four traditional schools of Islamic jurisprudence altogether.

- ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, Internet source: >http://www.exboard.com, http://pub63.ezboard.com/fyoungmuslimsfrm4.showMessage?topicID=30.topic, p. 4, (11/7/01), — originally on http://www.azzam.com, now suspended from the web.

- Abdullah ‘Azzam, Ilhaq bil-Qafilah (Join the Caravan), Conclusion, at http://www.religioscope.com/info/doc/jihad/azzam/caravan_6_conclusion.htm.

- Radical Islamists believe that no legitimate Islamic state has existed since the time of the Prophet and the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs (634-661 AD), Muhammad’s four immediate successors (Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and ‘Ali).

- Shaykh ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam on Jihad, Internet source: http://calvin.usc.edu/~jnawaz/ISLAM/JIHAAD/Azzam.Jihad.html, (11-15-01).

- Muhammad ‘Abd al-Salam Faraj, “Al-Farida al-Gha’iba,” in Jansen, The Creed of Sadat’s Assassins, p. 167.

- ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, Ilhaq bil-Qafilah (Join the Caravan), Part Three, Internet source: http://www.soa.uc.edu/org/msa/mssn/joinaa.html.

- Ibid. Part One.

- ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, Internet source: http://pub63.ezboard.com/fyoungmuslimsfrm4.showMessage?topicID=30.topic, p. 4, (7 November 2001).

- See Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), p. 131.

- ‘Azzam, Ilhaq bil-Qafilah (Join the Caravan), Part Three.

- Roy, Afghanistan, p. 87.

- Michael Griffin, Reaping the Whirlwind: The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan (London: Pluto Press, 2001), pp. 24-26, 136-37.

- On the Wahhabi movement in Afghanistan, see Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, Shah ‘Abd Al- Aziz: Puritanism, Sectarianism, Polemics and Jihad (Australia: Ma’rifat Publishing House, 1992).

- Sayyaf was a nominal member of the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan, but his field commanders did little fighting against the Taliban in 2001-02. Sayyaf is suspected by some of having a hand in the assassination of Tajik commander Ahmad Shah Massoud in September 2001. Sayyaf vouched for the assassins (posing as Algerian journalists) before they arrived in Massoud’s camp.

- Sheikh ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, “Martyrs: The building blocks of nations,” Extracts from the lectures of Sheikh ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam titled “Will of the Shaheed” and “A Message from the Shaheed Sheikh to the Scholars,” Internet source: http://www.azzam.com (29 January 2003).

- “Shaykh ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam on jihad,” Internet source: http://calvin.usc.edu/~jnawaz/ISLAM/JIHAAD/Azzam.Jihad.html (15 November 2001).

- The four schools of Islamic jurisprudence are all named for their founders: first, Hanafite (Abu Hanifa, d.767), found in Afghanistan, India, China, Turkey, and other ex-Ottoman territories; second, Malikite (Imam Malik, d. 795), found in Arabia, Upper Egypt, Sudan, West Africa, and parts of North Africa; third, Shafi’ite (Imam al-Shaf’I), found in Syria, South Arabia, Lower Egypt, Malaysia, East Africa, and Indonesia; fourth, Hanbalite (Imam Ibn Hanbal, d. 855), found almost exclusively in Arabia, where it has become closely linked to the Wahhabist movement. (Ibn Taymiyah was a member of the Hanbalite school, whose founder urged obedience to the government). ‘Azzam warned incoming mujahidin that the Afghans knew only the Hanafi school, and were likely to regard anything else as un-Islamic.

- ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, Ilhaq bil-Qafilah (Join the Caravan), Part Two, Internet source: http://www.soa.uc.edu/org/msa/mssn/joinaa.html. ‘Azzam believed that women could assist in the jihad through nursing, education, and assisting refugees, but must be accompanied by a nonmarriageable male guardian.

- For example, see, “Shaykh ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam on Jihad,” Internet source: http://calvin.usc.edu/~jnawaz/ISLAM/JIHAAD/Azzam.Jihad.html, (15 November 2001).

- http://www.mideast.web.org/osamabinladen3.htm.

- Yaseen Noorani, “The Lost Garden of al-Andalus,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 31, no. 2 (May 1999), p. 239.

- ‘Azzam, Ilhaq bil-Qalifah (Join the Caravan), Conclusion.

- The hadith in question quotes the Prophet as returning from battle and saying, “We have returned from the small jihad to the great jihad.” He was asked, “What is the great jihad, O Apostle of God?”, and Muhammad replied, ‘The jihad against the soul.'”

- Olesen notes that al-Banna himself retained a respect for early Sufist thought, but “among his followers there was a widespread revulsion and contempt for Sufism, which was considered a phenomenon of Greek-Hindu origin with no relation to Islam. The rejection of Sufism was not only doctrinal, but also rooted in the activist strategy of the Ikhwan, as Sufism was seen as drugging the masses, inspiring them to a spiritual withdrawal from life, being useless members of society and thus forming an obstacle to progress.” Olesen, Islam and Politics in Afghanistan, p. 248.

- ‘Azzam, Illhaqbil-Qalifah (Join the Caravan), Conclusion.

- Muhammad ‘Abd al-Salam Faraj, Al-Farida al-Ghaiba, in Jansen, The Creed of Sadat’s Assassins, p. 201, §88.

- Steven Emerson, American Jihad: The Terrorists Living Among Us (New York: Free Press, 2002), p. 130. The ethnic-Arab Atlantic Avenue area of Brooklyn was host to several Islamist mosques and organizations, including the Al-Kifah Afghan Refugee Center, an important conduit for recruiting and fundraising.

- ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, Internet source: http://www.ezboard.com, http://pub63.ezboard.com/fyoungmuslimsfrm4.showMessage?topiciD=30.topic, p. 4 (7 November 2001).

- Emerson, American Jihad, p. 131.

- General Hamed Gul, Director General of Pakistan’s Directorate of Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) was removed from his post after the failure of the siege of Jalalabad. Gul had actually spoken out against an attack made without air cover, anti-aircraft guns, or artillery. See Edgar O’Ballance, Afghan Wars 1839-1992: What Britain Gave Up and the Soviet Union Lost (London: Brassey’s, 1993), p. 202.

- Yoni Fighel, International Policy Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT), 27 September 2001, Internet source: http://www.ict.org.il/articles/articledet.ctm?articleid=388, (7 November 2001).

- Interview with Abu ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, Al-Sirat Al-Mustaqeem (The Straight Path), no. 33, (Aug. 1994), Pakistan. At the time of the interview, al-‘Aziz’s command was integrated with the 7th Battalion of the Bosnian Army. The mujahid was eventually imprisoned by the Saudis.

- ‘Azzam, “Martyrs: The building blocks of nations.”

- Reuel Marc Gerecht, “The Terrorists’ Encyclopedia,” Middle East Quarterly (Summer 2001), p. 81. Gerecht was a CIA agent from 1985 to 1994.

- See “Communique from Emir Khattab, Mujahideen attack Russian base in Dagestan,” (Parts 1- 2), Azzam Publications, MSA News, 29 December 1997, Internet source: http://msanews.mynet.net/MSANEWS/199712/19971228.1.html, (19 August 1999).

- Hamid Mir, quoted in: Scott Balduf, “The ‘Cave-Man’ and al-Qaeda,” Christian Science Monitor (31 October 2001).

- ‘Azzam, Ilhaq bil-Qalifah (Join the Caravan), Conclusion.

- ‘Azzam, “Martyrs: The building blocks of nations.”