Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies

Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies

Strategic Datalink no. 138

August, 2006

Andrew McGregor

Introduction

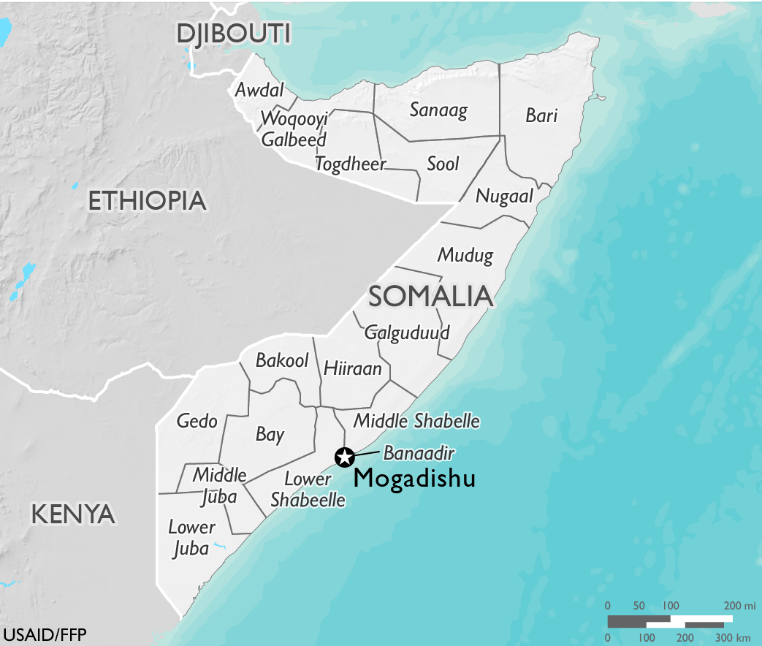

What began as a series of skirmishes between Islamist militias and Somali warlords who styled themselves as the “Anti-Terrorist Alliance” (ATA) [1] for control of Mogadishu’s neighbourhoods earlier this year has escalated into a conflict that now threatens to engulf the strategically-located Horn of Africa. The defeat of the warlords has allowed the Islamists to spill out of Mogadishu into central and southern Somalia, where they are consolidating their control. The latest political upheaval in the “failed state” of Somalia is based on a volatile combination of Islam and ethnic-based irredentism that is pulling in its mutually hostile neighbours of Eritrea and Ethiopia. The United States is concerned that the moderate Muslim leadership has been replaced by veterans of al-Ittihad al-Islami (AIAI), a militant group found on the US and UN lists of designated terrorist organizations.

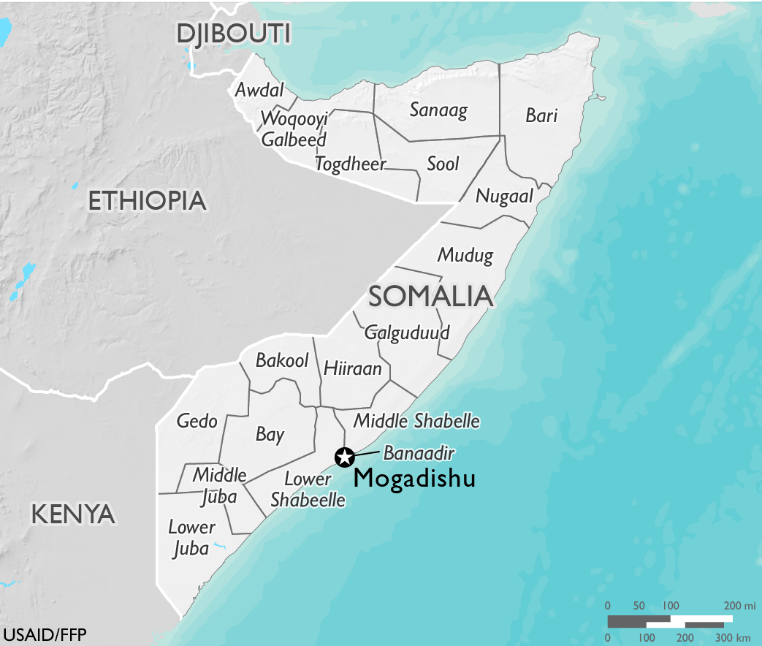

Somalia’s Islamist revolution bears some resemblance to the situation in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s, when the Islamist Taliban movement arose to challenge the dominance of warlords who had carved the nation into a variety of mutually hostile fiefdoms. The Taliban’s popularity was the result of its ability to restore law and order in a post-civil war wasteland through the application of Islamic law. Somalia’s “Islamic Courts” arose in 1992, providing a semblance of order in lawless Mogadishu. A reputation for honesty and a willingness to restore law and order through the application of Shari’a (Islamic) law in areas under their control gave the movement a following. Unification of the courts and their attendant militias through the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) gave the Islamists the strength to defeat the warlords who have laid waste to Somalia for the last 15 years and move out of Mogadishu to spread their movement into central and southern Somalia.

Somalia’s Islamist revolution bears some resemblance to the situation in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s, when the Islamist Taliban movement arose to challenge the dominance of warlords who had carved the nation into a variety of mutually hostile fiefdoms. The Taliban’s popularity was the result of its ability to restore law and order in a post-civil war wasteland through the application of Islamic law. Somalia’s “Islamic Courts” arose in 1992, providing a semblance of order in lawless Mogadishu. A reputation for honesty and a willingness to restore law and order through the application of Shari’a (Islamic) law in areas under their control gave the movement a following. Unification of the courts and their attendant militias through the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) gave the Islamists the strength to defeat the warlords who have laid waste to Somalia for the last 15 years and move out of Mogadishu to spread their movement into central and southern Somalia.

The Islamists’ unification project seeks to succeed with home-made solutions where no less than 14 separate international efforts to restore order in the nation have failed since 1991. The ICU offers the first real alternative to the clan-based politics that have foiled every attempt to restore governance in Somalia. Neighbours of the turbulent country fear, with good reason, that at least some of the Islamists seek to realize the concept of “Greater Somalia,” an expanded Somali homeland that would include the whole or parts of four nations and one pseudo-state (Somalia, Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia and Somaliland).

Battlefield Mogadishu

Many of the ATA warlords were minister in Somalia’s new government, which formed in Kenya in 2004 and moved into the southern Somali city of Baidoa last year. The warlords effectively abandoned their cabinet posts in the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) to take on the Islamist in Mogadishu. The creation of the ATA in February 2006 was a rather transparent attempt by the Somali warlords to adopt the rhetoric of the “War on Terrorism” and harness the support of the United States against their Islamist challengers. It quickly became the practice for Somali warlords and politicians to label all their opponents as members of al-Qaeda. Nonetheless, the strategy was successful in the short-term, with the US abandoning the long and difficult process of building the TFG in favour of supporting rapacious militia leaders with a long record of violent criminal activity. In the process, the US has lost much of its influence in the area.

The city of Baidoa, where the transitional government established itself until it could occupy Mogadishu, has been subjected to growing insecurity since the TFG arrived. The government hired 1,000 militiamen to provide security, but their failure to provide shelter or provisions for the militia members left them to forage on their own, even robbing MPs of the new government. [2] As ICU fighters approached Baidoa, 130 TFG militiamen defected to the Islamists, complaining of neglect from the government. [3] In mid-July, as many as 5,000 Ethiopian troops moved into Baidoa and surrounding towns to protect the Ethiopian-backed TFG. The ICU leader described the TFG as a tool of Addis Ababa, and called for a “holy war” by Somalis against the Ethiopian troops in Baidoa. [4] As tensions rose, Ethiopia responded with a vow to “crush” the Somali Islamists if they crossed into Ethiopian territory. [5]

Islam itself is not necessarily the driving force behind the revolution. As Somali journalist Bashir Goth puts it:

The Somali people have found the idea of finding safety in their own neighbourhoods, setting up their own bakeries and groceries, sending their children to school, albeit Islamic madrasas, and building their lives and peace in small steps to be more practical and attainable goals than building hopes on the return of a central government and restoration of peace and stability to a country that has been fragmentized beyond reparation. [6]

Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys

Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys

The Islamists

Since the Islamist victory in Mogadishu, ICU leadership has passed to a controversial figure, Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys, 61, who is wanted on terrorism charges by US and Ethiopian authorities. Shaykh Aweys, a former colonel in the prison service and later vice-chairman of Al-Ittihad al-Islami, asserts that American claims of an al-Qaeda presence in Somalia are nothing more than “a figment of their imagination,” citing Somalia’s complicated social structure, which is not easily penetrated by outsiders. [7] At Shaykh Aweys’ right hand is Adan Hashi Ayro, a violent extremist believed responsible for ordering the murder of four expatriate aid workers, a BBC reporter and a number of Somali politicians. A veteran of the jihadist campaign against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, Ayro’s most notorious action was to order the disinterment of 700 bodies from an Italian colonial cemetery in Mogadishu, tossing the remains into a nearby garbage tip.

Adan Hashi Farah Ayro

Adan Hashi Farah Ayro

AIAI is an Islamic organization that (like Hizbullah) has militant and charitable wings. The group carried out attacks in Ethiopia in the mid-1990s until a cross-border military response devastated the group. Ethiopia’s concern over the revival of the AIAI is natural; Prime Minister Meles warns that “Any movement which is led by this organization is a threat to our country.” In language familiar from another conflict, he adds: “We have all the rights to take the necessary action in a bid to prevent any threat to our country.” [8]

Bin Laden has encouraged the ICU to complete their control over Somalia, but the arch-terrorist is unlikely to have influence over any but a small number of Somalia’s Islamists. As in Darfur, Bin Laden’s interest in Somalia is largely unappreciated by the locals. TFG Prime Minister ‘Ali Muhammad Gedi angrily reminded the al-Qaeda leader that Somalis were practicing Islam long before Bin Laden’s birth and that he was mistaken to pose as a leader of international Islam. [9] Shaykh Aweys was more reticent in commenting on Bin Laden’s praise of the ICU with an American newsmagazine: “Everybody in the world has a right to say whatever they want or to comment how they want. That is not our responsibility.” [10]

Shaykh Aweys denies any personal ties to al-Qaeda and suggests that President George Bush should be indicted for war crimes related to his alleged support for Somalia’s warlords. “Bush filled suitcases with cash for the warlords so that they could kill people. He must be brought to justice.” [11] President Bush has also been sharply criticized by representatives of the TFG for supporting the ATA, a move seen as undermining the transitional government. Shaykh Aweys favours the establishment of an Islamic state in Somalia and says that Al-Ittihad al-Islamiya is no longer active in the country.

The US accuses Somalia’s Islamists of harboring three suspects wanted for the 1998 bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. The three suspects, none of whom are Somali, are Abu Taha al-Sudani (Sudanese), Salah ‘Ali Salah (Kenyan) and Qasim ‘Abdullah Muhammad (Cormoran). Having failed to obtain them through support for the “anti-terrorist” warlords, the US State Department was placed in the embarrassing position of then having to ask the ICU to turn them over. Not surprisingly, the ICU has disclaimed all knowledge of the three men. Shaykh Aweys has his own view on al-Qaeda’s terrorism; “When there is fighting, it is a fight whether you fire a gun or whether you send a plane into the World Trade Center. Since Obama was fighting against his enemy, he could use any tactic he had available to him.” [12]

Somali Islamists by no means share a common agenda. Some have political ambitions while others have spiritual focus. At the “moderate” end of the movement, the Sufi lodges (represented by umbrella group Ahl Sunna wa’l-Jama’a) are dedicated to refuting the views of radical groups like the AIAI. Even the Salafists (conservative reformers) are divided between those who espouse violence and those who oppose it. One major Islamist group, Harakat al-Islah, favours democracy and condemns political violence, putting them at odds with the AIAI. Beyond a general belief among the factions that Islam should assume a core role in any new government, there is little agreement on the details. [13]

Nevertheless, religious extremists have great influence in the Islamist movement. ICU leader Shaykh ‘Abdallah ‘Ali, for example, has threatened to execute any Somali who fails to pray every day. While the majority of the ICU may be termed moderate in its interpretation of Islamic law, the extremists have taken control of the direction of the Islamist revolution. The excesses of their followers, including breaking up wedding parties, smashing musical instruments, shooting theatre owners, flogging young people in public and banning the viewing of World Cup soccer matches, have quickly discredited the ICU and threaten their acceptance by Somalis who are otherwise eager to support anyone who can bring an end to the constant fratricidal warfare. Shaykhl Aweys, a populist at heart, appears to understand the danger and has promised to bring to trial the ICU gunmen who killed two Somalis watching a World Cup match in Dhuusa Marreeb. [14]

The ICU, like the warlord coalition, receives funding from Somalia’s business community, but there are questions about other sources of financial support. Aweys refutes US charges that his movement is being armed and funded by Saudi Arabia and Yemen (both alleged US allies in the “War on Terrorism”). [15] Eritrea has responded to similar US charges of arming the ICU by challenging the State Department to make its evidence public. The Eritrean government contends that such “subtle disinformation campaigns” are “aimed at denting its impeccable record in combating international terrorism.” [16]

The Horn on the Brink of War

In the morning of 26 July, a massive Ilyushin-76 cargo plane carrying Kazakh markings made a landing at the rarely used Mogadishu Airport. It was reported that the aircraft was leased by Eritrea to supply the ICU with a vast quantity of arms. [17] The TFG claims that Eritrean troops are present in Mogadishu and the Lower Shabelle region, but has provided no evidence. [18] By the end of July, TFG premier Muhammad ‘Ali Gedi was also accusing the unlikely trio of Iran, Egypt and Libya of arming the ICU.

From 1998 to 2000, Ethiopia and Eritrea engaged in a bloody and incomprehensible (at least to outsiders) border war, fought with First World War tactics in a lifeless and useless strip of contested territory. The war’s inconclusive end left both sides spoiling for another go. Ethiopia characterizes Eritrean support backing for Shaykh Aweys as support for international terrorism. Ethiopia also appears to have violated the arms embargo with convoys of arms and ammunition destined for the ATA. [19] At a recent African Union summit Ethiopia accused Eritrea of subverting neighbouring countries and practicing terrorism. [20] Prime Minister Meles Zenawi blames recent unsolved bombings in Addis Ababa on an “unholy alliance” between Eritrea and Somalia’s Islamists. [21] Ethiopia claims that the ICU has been penetrated by elements of al-Qaeda, but still states its willingness to negotiate with “moderate” groups within the Islamist coalition.

Eritrea questions the aims of US policy in the region, which it describes as “military adventurism.” A statement from the Eritrean Ministry of Information suggests that; “the goal of these interventions is not to uproot terrorism as it is said, but rather… to assure domination and plunder and thereby guarantee the advent of [a] new colonialism.” The agent of this policy is the Ethiopian TPLF regime, [22] described as a “decrepit and decayed regime administered entirely by none other than the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States.” [23] Eritrea is believed to be supplying armed Somali separatist movements in both southeastern Ethiopia (the Ogaden National Liberation Front – ONLF) and northern Kenya (the Oromo Liberation Front – OLF) as part of an aggressive regional foreign policy that has also brought condemnation from Khartoum for Eritrea’s support of the rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in Darfur.

Hassan ‘Abdullah Hersi al-Turki

Hassan ‘Abdullah Hersi al-Turki

Ethiopia fears that a revived Islamist Somalia might provide support for the ONLF, a Somali guerrilla force engaged in a low-intensity conflict with Addis Ababa. There are four million ethnic Somalis in Ethiopia’s Ogaden Desert region, occupying about a quarter of the nation’s territory. One of the ICU’s most active commanders is Hassan Abdullah Hersi al-Turki, a long-time Ogaden separatist, member of al-Ittihad al-Islamiya and a US-designated al-Qaeda suspect. Al-Turki is certain to see the ICU as a vehicle for intensifying the Ogaden conflict, particularly with the support of Shaykh Aweys, who refers to the region as “part of Somalia.”

Only months after the 1991 fall of longtime President Mohamed Siad Barre, the northern province of Somalia seceded and formed the state of Somaliland, still unrecognized anywhere in the international community despite a solid record of stability and development compared to the shattered remains of central and southern Somalia. The state was a former British colony, part of the tripartite imperial division of Somali territory that included Italian and French colonies. Somaliland continues to stand aloof from the revolution, but the Islamists may have an appeal that the warlords never had in the region. In the meantime it appears that Aweys already has designs on Somaliland’s independence. Fifteen men, including Aweys, have been charged with participating in a failed terrorist attack in the Somaliland city of Hargeysa in September 2005. The attack was apparently designed to disrupt elections in the same month. Eight men are currently on trial under charges that carry the death penalty, while seven others, including Aweys, are being tried in absentia. Hargeysa prosecutors claim to have videotapes in which Aweys and his lieutenant Adan Hashi Ayro advise the men to carry out terrorist strikes to eliminate the influence of “infidels.” [24]

Somaliland has useful experience in conflict resolution in a local context that should be called upon to help settle the conflict. In the past, Somali leaders have shunned such input, preferring instead to plot the re-absorption of Somaliland into a non-existent Somali state. A number of leading members of the TFG have origins in Somaliland and would like to reassert their authority there.

To the northwest of Somaliland, Djibouti (former French Somaliland) hosts the US Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa, a combined military unit of over 1,000 men stationed in a major French military base. The unit is designed to react rapidly to terrorist threats in the region. Djibouti’s foreign minister announced in mid-July that US forces would not be allowed to use the territory as a base for counter-terrorist attacks on Somalia. [25]

Security Implications and International Intervention

Piracy continues to plague the Somali coastline with no navy or coast-guard to enforce maritime law. The TFG has engaged two private firms, Northbridge Services Group (NSG) and the African Institute for Maritime Research (AIMR) to provide security along the coast, eliminate the dumping of toxic waste (another chronic problem) and organize a Somali coastal defence force. In return, NSG and AIMR have been given the right to “negotiate and authorize” the licensing of oil concessions and exploration.

The UN arms embargo on Somalia has been a failure, with the UN Security Council citing “continuous violations.” The TFG president has urged that the embargo be lifted (presumably to rearm his own forces), but has had difficulty finding anyone on the Security Council who (at least officially) thinks that Somalia’s greatest need is for more arms. Nevertheless, President ‘Abdullahi has found supporters for rearmament in the African Union seven nation Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an East African regional assembly. The ICU has urged that the embargo should continue. [26]

The United States is opposed to IGAD and African Union plans to deploy African peacekeepers (possibly Ugandan and Sudanese) in Somalia. Shaykh Aweys is also opposed, and has warned that any peacekeeping mission will be met with resistance, saying: “The neighbouring countries have geo-political interests in Somalia and to consider them peacemakers is a recipe for violence and renewed clashes, which would affect the whole region.” [27]

Conclusion

Factionalism is likely to resurface within the ICU under Aweys’ radical leadership. The temptations of traditional clan politics are a constant challenge to the religious unity of the ICU and the movement risks losing popular support by dragging Somalia into an unpromising and costly campaign to establish “Greater Somalia.” Even an attempt to bring the autonomous Somali region of Puntland or quasi-independent Somaliland under ICU control will spark another round of civil conflict in a war-weary population. Puntland native ‘Abdullah Yusuf Ahmad is TFG President and played a large part in destroying al-Ittihad al-Islami in 1997.

Arab League-sponsored talks in Khartoum between the ICU and the TFG have largely broken down amidst mutual accusations of ceasefire violations. The ATA has collapsed and the transitional government is falling apart through assassinations and resignations while losing most of its legitimacy as Ethiopian troops protect it from the citizens it purports to rule.

Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad

Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad

Still in the wings is Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad, former chairman of the ICU. The US and the TFG have indicated they are willing to hold talks with the Sufi master and his group, but not with ICU chairman Shaykh Aweys, which TFG prime minister ‘Ali Muhammad Gedi likens to having face-to-face talks with Osama Bin Laden. [28]

Interest in foreign adventures or the international jihad is low in the rank-and-file of the Somali Islamist movement, but military intervention by Ethiopia will give the factions common cause and bring an inevitable and unified response. Eritrea, northern Kenya and Ethiopia’s Ogaden region could quickly be drawn into any Somali-Ethiopian conflict. The bellicosity, posturing and inflexibility of all parties in the region has the potential to unleash yet another vast crisis throughout the long-suffering Horn of Africa.

Endnotes

- The full name of the organization is “The Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism.”

- IRIN, April 3, 2006.

- SomaliNet, July 20, 2006.

- Radio Shabelle, July 21, 2006.

- Shabelle Media Network, July 22, 2006.

- Somaliland Times, June 24, 2006.

- Al-Sharq al-Awsat, April 12, 2006.

- Radio Ethiopia, June 27, 2006.

- Shabelle Media Network, July 2, 2006.

- Rod Nordland, “Heroes, Terrorists and Osama,” Newsweek, July 22, 2006.

- Somali Broadcasting Corporation (Puntland), July 10, 2006.

- Nordland, op cit.

- Anouar Boukhars, “Understanding Somali Islamism,” Terrorism Monitor 4(10), May 18, 2006.

- HornAfrik Radio, July 5, 2006.

- Al-Sharq al-Awsat, July 2, 2006.

- Eritrean Ministry of Information Shabait website, July 1, 2006.

- Shabelle Media Network, July 26, 2006.

- Ibid

- Shabelle Media Network, May 24, 2006.

- Walta Information Centre, July 4, 2006.

- Ethiopian TV, July 4, 2006.

- TPLF = Tigray People’s Liberation Front, the leading party in the Ethiopian ruling coalition.

- Eritrean Ministry of Information Shabait website, July 1, 2006; June 28, 2006.

- Somaliland Times, July 1, 2006.

- Al-Sharq al-Awsat, July 12, 2006.

- HornAfrik Radio, July 10, 2006.

- Shabelle Media Network, July 17, 2006.

- HornAfrik Radio, July 10, 2006.

Hezbollah Fighters with Katyusha Rocket Emplacement (AP)

Hezbollah Fighters with Katyusha Rocket Emplacement (AP) An Iranian official recently confirmed that Zelzal-2 rockets, with a stated range of 200 kilometers (although this figure may be significantly exaggerated), had been provided to Hezbollah by Iran for use “in defense of Lebanon” (Haaretz, August 5). The 610mm Zelzal-2 is a 3,500 kilogram rocket with a 600 kilogram high-explosive warhead, first delivered to Revolutionary Guard units in Lebanon in 2002. Israeli intelligence believes the missile is capable of reaching the northern suburbs of Tel Aviv. Although the rocket is unguided and difficult to use, the threat from the Zelzal-2 is taken seriously, with U.S.-made Patriot anti-missile systems deploying near Netanya to guard Tel Aviv. The Patriot system is useful only against larger, longer-range rockets, with no effectiveness against the smaller Katyusha types.

An Iranian official recently confirmed that Zelzal-2 rockets, with a stated range of 200 kilometers (although this figure may be significantly exaggerated), had been provided to Hezbollah by Iran for use “in defense of Lebanon” (Haaretz, August 5). The 610mm Zelzal-2 is a 3,500 kilogram rocket with a 600 kilogram high-explosive warhead, first delivered to Revolutionary Guard units in Lebanon in 2002. Israeli intelligence believes the missile is capable of reaching the northern suburbs of Tel Aviv. Although the rocket is unguided and difficult to use, the threat from the Zelzal-2 is taken seriously, with U.S.-made Patriot anti-missile systems deploying near Netanya to guard Tel Aviv. The Patriot system is useful only against larger, longer-range rockets, with no effectiveness against the smaller Katyusha types.