Andrew McGregor

November 13, 2009.

For nearly a year now, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of Somalia has been waging a life or death struggle for survival against the repeated assaults of a radical Islamist opposition; an opposition that remains unsatisfied with the appointment of a fellow Islamist as president and the implementation of Shari’a as the law of the land. Led by the former leader of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad, the TFG has little effective control over the country outside of a few Mogadishu neighborhoods, despite backing from the United States, the United Nations and the African Union (AU). Members of the TFG work under the constant threat of assassination, keeping many parliamentarians outside of the country. The Islamist militants demonstrated their reach in a bombing that killed the Minister of Security, Colonel Umar Hashi Adan, in Hiraan province last June (al-Jazeera [Doha], June 19; al-Arabiya [Dubai], June 18). Possible directions for the future of the Islamist insurgency in Somalia are offered below.

Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab

Leadership of Harakat al-Shabaab Mujahideen

The leadership of Somalia’s Harakat al-Shabaab Mujahideen (Youth Mujahideen Movement) appears to be in a state of flux at the moment. The movement’s reclusive leader, Shaykh Ahmad Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr” (a.k.a. Ahmad Abdi Aw Muhammad, a.k.a Shaykh Mukhtar “Abu Zubayr”), was seriously wounded in May when a suicide bomb went off prematurely in a safe house where an al-Shabaab meeting was being held (Garowe Online, May 18, May 20; Waagacusub.com, May 18). Little has been heard of him since. Only days after the blast, the public face of the movement, Shaykh Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur,” was replaced by Shaykh Ali Mahmud Raage (a.k.a. Shaykh Ali Dheere) (Radio Simba, May 21; Shabelle Media Network, May 22). No explanation was offered for the sudden change and Mukhtar Robow briefly faded from public view before reappearing with a statement threatening the administrations of semi-autonomous Puntland and Somaliland, a self-declared independent state (AllPuntland.com, October 31). He was then reported to have appeared at an anti-Israel demonstration in Baydhabo, where he announced that there would be a hunt for anyone who holds Israeli citizenship or who might be Jewish (Puntland Post, October 31). Though there are no public signs of enmity, there is always the possibility that Godane’s death or prolonged incapacitation could set off a power struggle within the Shabaab leadership.

Factionalism in the Islamist Opposition

The Hizb al-Islam movement, led by Shaykh Dahir Aweys, is the successor to Shaykh Aweys’ earlier organization, the Eritrean-based Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia – Asmara (ARS-Asmara). While Hizb al-Islam is larger than al-Shabaab, the latter is better organized and possibly better equipped. At the moment, Hizb al-Islam operates as an ally of al-Shabaab in the fighting in Mogadishu, though there are differences between the two groups that could erupt into open warfare at any moment. There have already been skirmishes between the groups.

Al-Shabaab’s Salafist orientation has brought it into conflict with Somalia’s Sufis, who have responded to the desecration and destruction of their shrines and places of pilgrimage by forming their own formidable militia, the Ahlu Sunnah wa’l-Jama’a. With Sufis rather than Salafists representing mainstream Islam in Somalia, al-Shabaab has created a determined enemy that is unlikely to cease fighting until the radical Islamists have been defeated.

Internationalization of the Somalia Conflict

Reflecting its narrow vision of what constitutes righteous rule, al-Shabaab has, in the last year, threatened all of its neighbors as well as Burundi, Uganda, Ghana, Israel and the United States. The conflict already has an international element, with Ugandan and Burundian troops of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) deeply involved in the active defense of the TFG, Ethiopian troops conducting cross-border incursions after a lengthy and costly occupation of Somalia, and U.S. airstrikes being launched on terrorist targets. The TFG has also issued appeals for neighboring countries, including Kenya, Djibouti and Yemen, to send troops to Somalia to bolster the government (al-Jazeera, June 22). It is clear that the TFG has little local support it can rely on and would quickly collapse without international backing.

Al-Shabaab is active in fundraising and recruitment of Somali diaspora groups in Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands, Canada and the United States (NRC Handelsblad, November 13). While these activities have not yet escalated to politically-motivated violence, the possibility exists, particularly as al-Shabaab becomes more vocal in its threats to Western states. The recent arrest of three Somali men accused of targeting a military installation in Australia with a suicide attack has alarmed other nations hosting large Somali communities (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, August 7).

Al-Shabaab has pledged retaliation against the United States in response to the mid-September airstrike that killed al-Qaeda suspect Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 8). Though direct retaliation is probably beyond the means of al-Shabaab, it is entirely possible that its agents in the American diaspora could arrange some kind of internal attack by young people sympathetic to the Islamist cause in Somalia. Al-Shabaab leader Shaykh Abdi Ahmad Godane has made clear the international ambitions of the movement: “We will fight and the wars will not end until Islamic Shari’a is implemented in all continents in the world and until Muslims liberate Jerusalem…” (AFP, May 13). For the moment these goals may exceed the grasp of a movement that has yet to take Mogadishu.

What Will Happen in Somalia in the Event of a Shabaab Victory?

• Popular support for the movement (which is difficult to gauge but certainly does not include a majority of Somalis) would inevitably diminish due to the movement’s ordinances against popular pastimes such as watching soccer or chewing qat, as well as the movement’s affection for hudud punishments for violations of Shari’a, such as stonings, amputations, beheadings and whippings. Though Shari’a law has already been implemented in Somalia, al-Shabaab is only interested in its own interpretation, one not shared by a majority of Somalis.

• Shabaab’s foreign connections will work against them. Shabaab’s international ties are all with non-state actors, none of which will be of any assistance in running a state. On the contrary, these ties will invite embargoes and other sanctions. International isolation and the suspension of humanitarian aid are likely outcomes for an organization which has referred to UN aid agencies as “enemies of Islam.”

• The movement’s revanchist program to establish a “Greater Somalia” places it immediately at odds with every one of Somalia’s neighbors. Any attempt to expand Somalia’s borders as part of the development of an Islamic Caliphate in the Horn of Africa would require full national support, in the absence of which disaster would surely befall the movement and the nation. Al-Shabaab’s revanchism would quickly mobilize regional opposition.

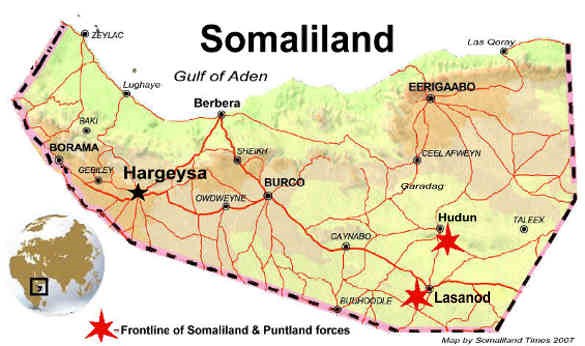

• Civil war with Puntland and Somaliland would quickly follow an al-Shabaab victory in Mogadishu. Al-Shabaab terrorist attacks on autonomous Puntland and self-declared independent Somaliland have already introduced political violence into these pockets of Somali stability. Shabaab’s declared intention is to bring both regions under the control of an Islamist caliphate, a program with almost no popular support in these two regions. With Puntland and Somaliland already embroiled in a bitter and occasionally violent border territorial dispute, the possibility of a three-sided civil war exists.

• Continued fighting with Ahlu wa’l Jama’a would be a near certainty with al-Shabaab hardliners appearing to have won the internal debate over the wisdom of deliberately antagonizing Somalia’s vast Sufi community through the continued destruction and desecration of Sufi shrines, graves and places of pilgrimage.

• Though al-Shabaab has cooperated with Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys’ Hizb al-Islam militia on the Mogadishu battleground, the Shabaab leadership has serious differences with the ambitious Shaykh Aweys and would likely prefer to exclude him from any Islamist administration. If Shaykh Aweys could keep his fighters from going over to al-Shabaab, further intra-Islamist fighting could be expected.

• Having very little influence with Somalia’s tribal elders, the movement has little expectation of resolving existing clan disputes or preventing the eruption of new ones, leaving little hope that the movement could impose stability without a massive increase in violence.

• Without a core of technical experts or experienced administrators, the inability of al-Shabaab to carry out the basic administrative functions of a national government would inevitably lead to the collapse of the regime, leaving Somalia in perhaps an irreparable state.

• The return of Ethiopia’s military would be a real possibility. The rise of Islamist forces in Somalia is likely to increase ethnic-Somali resistance to Ethiopian rule in the Ogaden region. If Addis Ababa has a choice between fighting the war in Somalia or their own in eastern Ogaden province, it will choose Somalia, especially if further U.S. arms and training are made available. The United States would like to act through a proxy in Somalia rather than open a new front in the War on Terrorism through direct military intervention.

• The possible effect of an al-Shabaab victory on the piracy situation is difficult to gauge. In the past al-Shabaab has expressed its opposition to piracy, even attacking a party of pirates at one point, though this was just as likely to be inspired by clan rivalries or a dispute over distribution of ransom money. Since most pirate activity emanates from Puntland, an al-Shabaab victory in Mogadishu might have little impact unless the movement acts to invade Puntland and end its semi-autonomous status. This would bring al-Shabaab into direct contact with the armed forces of neighboring Somaliland and an almost inevitable confrontation that would stretch al-Shabaab’s supply lines and capabilities in a region where they have little influence.

• An al-Shabaab victory would represent a major blow to African Union (AU) peacekeeping efforts. The AU mission to Darfur could be described as having a mixed record at best – in Somalia it has only been through the commitment of Uganda that AMISOM has survived. Though the mission has been bolstered by the addition of Burundian troops, it is still severely undermanned and subject to greater stress than ever since the AMISOM mandate was changed to provide for military action against the insurgents in Mogadishu. In the event of a TFG collapse, AMISOM troops and equipment (including artillery and armor) would have to be quickly evacuated, a capability the AU does not possess. With little peace to keep, the AU peacekeepers face daily combat losses and are subject to suicide bombings even in their own camps, such as the one that killed 17 Ugandan and Burundian soldiers on September 17, including the mission’s second in command, Major General Juvenal Niyoyunguruza of Burundi. The attack was retaliation for the U.S. airstrike that killed al-Qaeda operative Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan (New Vision [Kampala], September 17; Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 18). ).

• An al-Shabaab victory would present jihadis in other theaters with a temporary morale boost, but a large scale movement of jihadis to Somalia is still unlikely. Somali clannishness and factionalism are anathema to hardcore jihadis, who are in the habit of placing organizational needs and group identity over personal or tribal needs and identities. Lack of infrastructure and modern communications will inhibit rather than enhance international operations based in Somalia. The prevailing xenophobia of many Somalis does not offer the same sort of welcome and refuge al-Qaeda found in the Pashtun areas of Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan. Southern Somalia also offers a possible trap for global jihadis, as seen from the experience of the ICU in December 2006, when Ethiopian troops on land and U.S. ships at sea squeezed the ICU fighters towards a reinforced Kenyan border. Getting out of Somalia could be much harder than getting in if an international effort is mobilized against al-Shabaab.

• A mass exodus of Somali civilians would surely follow an al-Shabaab victory, leading to a further humanitarian crisis that might require international intervention. Already parts of Mogadishu have been largely depopulated and Somali refugees make desperate attempts to reach Yemen daily on craft that are barely seaworthy. With most land borders closed to refugees, smuggling people out of Somalia has become one of the few growth industries in Puntland, the closest point to Yemen.

• In the event of an al-Shabaab victory, the movement may ironically rely on Somali factionalism for its survival. Much the same way as the TFG only survives due to the inability of the Islamist opposition to unite effectively, al-Shabaab could survive for an extended time because of the inability of the anti-Islamist opposition to unite.

Conclusion

Despite international support, the TFG of President Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad appears to have little chance of survival. Almost continuous pressure from the armed Islamist opposition threatens to undermine the current administration, sending it to the same fate as the failed administrations of former President Abdullahi Yusuf and the earlier Transitional National Government (TNG) of Abdiqasam Salad Hassan. With little hope of relief from the apparently incessant warfare in south and central Somalia, there are signs that further attempts will be made to carve out independent, locally-ruled mini-states along the lines of Puntland and Somaliland. Combined with the entrenchment of clan rivalries and interference from neighboring states, regional interests and international powers, prospects for the establishment of a united Somalia at peace with its neighbors are disappointingly slim.

This article first appeared in the November 13, 2009 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

Former LRA field commander Charles Arop

Former LRA field commander Charles Arop Lord’s Resistance Army Fighters

Lord’s Resistance Army Fighters