Jamestown Foundation Special Commentary on Libya

Andrew McGregor

February 23, 2011

In recent days there have been reports that the Libyan regime of Mu’ammar al-Qaddafi has resorted to the use of foreign mercenaries to slaughter unarmed civilians protesting over four decades of rule by Qaddafi and his family. The Libyan government has been clear from the start that protestors could expect a “violent” response from the regime (al-Zahf al-Akhdar [Tripoli], February 19). Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s son, Sa’if al-Islam al-Qaddafi, warned viewers of Libyan state TV: “We will fight to the last man and woman and bullet” (al-Sayda TV, February 20).

Khaled al-Ga’aeem, the under-secretary of the Libyan Foreign Ministry, told al-Jazeera interviewers there was no truth to the reports of mercenaries: “I am ready – not only to resign from my post – but also set myself on fire in the Green Square – if it is confirmed that there were mercenaries from African states coming by planes” (al-Jazeera, February 22). However, citing his own reports from inside the country, the Libyan ambassador to India, Ali al-Essawi, has confirmed the use of African mercenaries and the defection of units of Libya’s military in response to their deployment (Reuters, February 22). In New York, defecting Libyan Deputy Ambassador Ibrahim Dabbashi called on “African nations” to stop sending mercenaries to defend the Qaddafi regime (New York Times, February 21).

Italian Aircraft Drops Grenades on Ottoman and Libyan Troops, 1911

Italian Aircraft Drops Grenades on Ottoman and Libyan Troops, 1911

The Libyan Origins of the Modern Jihad

Libya has turned to African fighters in the past. When a massive Italian army arrived on the Libyan coast in 1911 with the intention of seizing the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica for a new Roman Empire, they were met by a small but determined force drawn from all quarters of the Ottoman Empire. [1]

Though Ottoman soldiers were busy with wars in the Balkans and rebellion in Yemen, the defense of Libya became a popular cause in the army, with volunteers from across the empire crossing through the Italian blockade with the help of local people in neighboring Tunisia and Egypt. These volunteers, who included Enver Bey (a leading member of the “Young Turks”) and Mustafa Kemal (the founder of modern secular Turkey after the First World War), were largely motivated by patriotism or religion. To the surprise of the Turkish officers and the astonishment of the Italian generals, Libyan tribesmen suddenly began riding into the Turkish camps to offer their services. As the call for jihad spread south, fighters began to arrive from the Tubu tribes of Tibesti and the Tuareg tribes of the Fezzan. The dark-skinned Tubus would later be forced out of Libya into Chad by al-Qaddafi for being inconsistent with Qaddafi’s vision of a purely Arab nation after a member of Libya’s former royal family attempted to recruit Tubu mercenaries for use against Qaddafi in the early 1970s. [2] The Tuareg of Libya were ethnically “reclassified” from Berbers to Arabs.

Many fighters from the African interior had few connections with the Ottomans, but arrived to repel the infidel invaders from a sense of religious obligation, thus setting an example for later jihadis who would travel to the battlegrounds of Chechnya, Afghanistan and Iraq under a similar sense of obligation.

The Islamic Legion

Qaddafi also turned to a quasi-mercenary force to further his ambitions in Africa in the early days of his rule. The Islamic Legion (al-Failaka al-Islamiya) was a force of largely unwilling mercenaries recruited and deployed by Qaddafi to further his territorial ambitions in the African interior and advance the cause of Arab supremacy. Formed in 1972, the Islamic Legion was drawn mostly from young men from Sahelian countries who had migrated to Libya in search of work. Many were effectively “press-ganged” into service with the Legion. Though the organization worked closely with the Tajammu al-Arabi (Arab Gathering) to advance Arab supremacy in the Sahel and Sudan, the Legion was usually dominated by Tuareg and Zaghawa recruits despite neither group having any Arab heritage.

The Legion was deployed in the frontlines of a series of wars with Chad (supported by French Foreign Legion forces) in the 1980s. The Legion was disbanded in 1987 after Libya’s final defeat in these clashes, but the ongoing depredations of Darfur’s Arab Janjaweed have their origins in the Qaddafi-backed Tajammu al-Arabi. Many of the Tuareg who launched rebellions in Mali and Niger in the 1990s received their military training in the Islamic Legion.

Mercenaries to the Rescue

The current employment of mercenaries to do the “dirty work” usually assigned to Libya’s paramilitary security police speaks volumes about the regime’s rapidly dwindling faith in the willingness of state security forces to “fight to the last man” in defense of the regime. While the evidence of such recruitment is growing through video footage finding its way out of Libya, it is still impossible to tell in what numbers these mercenaries have arrived. Unconfirmed reports suggest the mercenaries arrived on a number of separate flights to both the Tripoli and Benghazi military airports, perhaps indicating a number of different recruitment sites (al-Arabiya, February 19; Jeel-Libya.net, February 19). The recruitment appears to have been undertaken quickly, either without the knowledge of the intelligence agencies and security services of their countries of origin, or with the full knowledge and approval of their originating states. Through a combination of largesse, aggressive diplomacy and military support (in the form of training, presidential protection units and stockpiles of old Soviet armaments), Qaddafi remains an influential figure in many parts of West Africa.

A number of mercenaries appear to have paid a high cost for their intervention in the Libyan uprising. Video has emerged of a number of slain “mercenaries” lying on the street or stretched out across a truck’s hood for display. [3]

Possible national origins for the mercenaries include:

Chad: Chadian mercenaries have been active in the Central African Republic for many years. There are also a large number of anti-government Chadian guerrillas who have recently found themselves unemployed after a peace treaty between N’djamena and Khartoum resulted in their expulsion from bases in Darfur. Many of these gunmen refused offers of repatriation to Chad, leaving them without work. Tensions between Chad and Libya eased after the International Court of Justice awarded the disputed Aouzou Strip to Chad in 1994. Since then, Chad’s President Idriss Déby has cooperated with the Libyan leader on a number of initiatives and agreements. Déby has been away from Chad throughout most of the Libyan crisis, following a state visit to China with meetings in Nouakchott and Abidjan (AFP, February 21).

French-Speaking Sub-Saharan Africa: Tunisians, Nigeriens and Guineans are among those mercenaries who have been captured, some still bearing identification documents.

English-Speaking Sub-Saharan Africa: Some of the mercenaries are reported to speak English (Radio France Internationale, February 20). Reports from Ghana indicate Ghanaians are being offered as much as $2500 per day to defend the Qaddafi regime. Advertisements for mercenaries have also begun to appear in Nigerian newspapers (Ghana Web, February 22).

The Libyan Army

In his televised address to the Libyan people, Mu’ammar’s son, Sa’if al-Islam al-Qaddafi, told Libyans: “The army will play a big role [in defending the regime], it is not the army of Tunisia or Egypt. It will support Qaddafi to the last minute” (al-Sayda (Libyan State TV), February 20; Quryna.com, February 21).

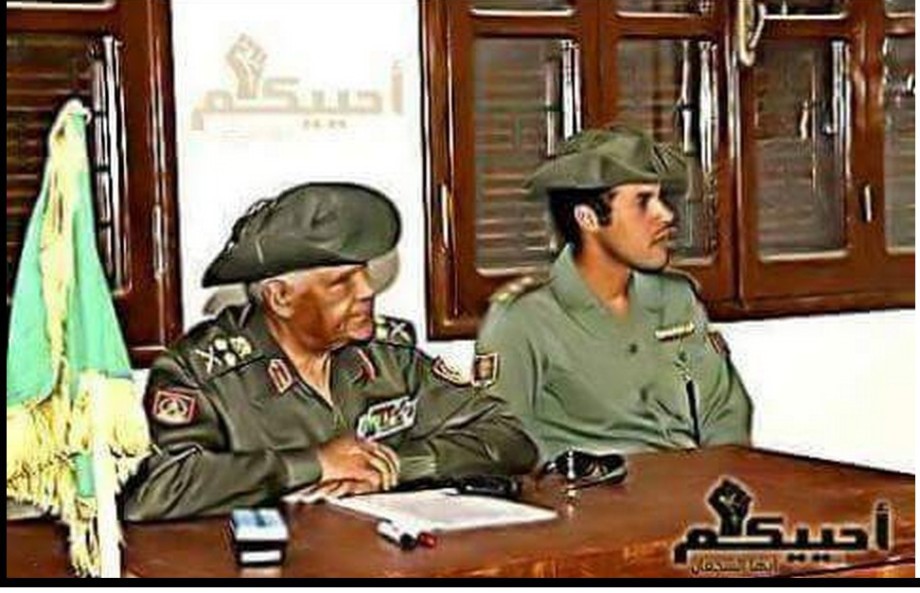

General Abu Bakr Yunis Jabr and General Khamis al-Qaddafi

General Abu Bakr Yunis Jabr and General Khamis al-Qaddafi

Bereft of real threats to its territory, whose security is guaranteed both by the strategic importance of Libya’s ample oil reserves and Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s considerable (if somewhat baffling) status in the African Union, Libya’s “Guide” has been able to indulge in periodic purges of his officer corps while keeping most elements of his armed forces under-armed and short of ammunition. The exception to this is the 32nd Brigade, popularly known as the “Khamis Brigade” after its leader, Khamis Abu Minyar al-Qaddafi, one of Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s seven sons. Khamis is a graduate of the Libyan Military Academy in Tripoli and received further training in Moscow at the Frunze Military Academy and the General Staff Academy of the Russian Armed Forces. The Brigade under his command typically receives better arms, equipment and salaries than the rest of the army and serves as a kind of Praetorian Guard to defend the regime. Brigade members have been active in trying to repress the demonstrations.

The Khamis Brigade was supplied with the British-made Bowman tactical communications and data system in a $165 million deal with General Dynamics UK, though the equipment has been modified through the removal of U.S. technology in the system (Defense News, May 8, 2008). [5] The Khamis Brigade has also taken part in joint exercises with the Algerian military (JANA [Tripoli], December 1, 2007).

Since Libya reconciled with the UK in 2008, the latter has become a major supplier of military gear, and even military training, though London has now revoked arms export licenses to Libya (Guardian, February 19). Units of the Special Air Service (SAS) have been involved in training Libyan Special Forces, unpopular duty for SAS veterans who were involved in a deadly decades-long struggle with the Libyan-armed Irish Republican Army (Telegraph, September 11, 2009). A December 2010 U.S. embassy cable released by Wikileaks also shows interest from Khamis al-Qaddafi and Sa’if al-Islam al-Qaddafi in obtaining U.S. made military equipment, including helicopters and parts for armored vehicles. [6]

Aside from the Khamis Brigade, most of the rest of the military has access only to obsolete Soviet-era equipment after enduring years of sanctions. This situation is not necessarily regarded as unfavorable by the regime, as it diminishes the chance rebel officers could mount their own coup similar to Colonel Qaddafi’s 1969 military takeover. Officers are subject to frequent transfers to prevent them from developing personal ties of loyalty with any one command. Though the senior ranks of the military are dominated by the “Guide’s” own Qadhadfa tribe, rivalries within the officer corps tend to be encouraged rather than discouraged to prevent an atmosphere of cooperation that could possibly lead to the creation of a junta.

Another son and prominent military figure is Colonel Mutassim al-Qaddafi. Mutassim received his training at the Cairo Military Academy before being given command of an elite unit in the Libyan army, where he gained a reputation for indiscipline and erratic behavior. At one point he was forced to take refuge in Egypt after reportedly marching on his father’s residence at the Bab al-Azizya barracks in Tripoli with detachments of his artillery. In 2002 he returned to Libya, where he was forgiven and promoted to Colonel (Jeune Afrique, May 19, 2010). In January 2007, Mutassim was made head of the National Security Council (Jeune Afrique, February 7, 2009).

Yet another son, Colonel Sa’adi Mu’ammar al-Qaddafi, took to local radio on February 19 to announce he had arrived in Benghazi to direct operations there (apparently after the resignation of Benghazi-based Colonel Abd al-Fatah Yunis), but little has been heard of him since (AP, February 19). First Lieutenant Hannibal Mu’ammar al-Qaddafi is a member of the military, but seems to play a minor role in comparison to his brothers.

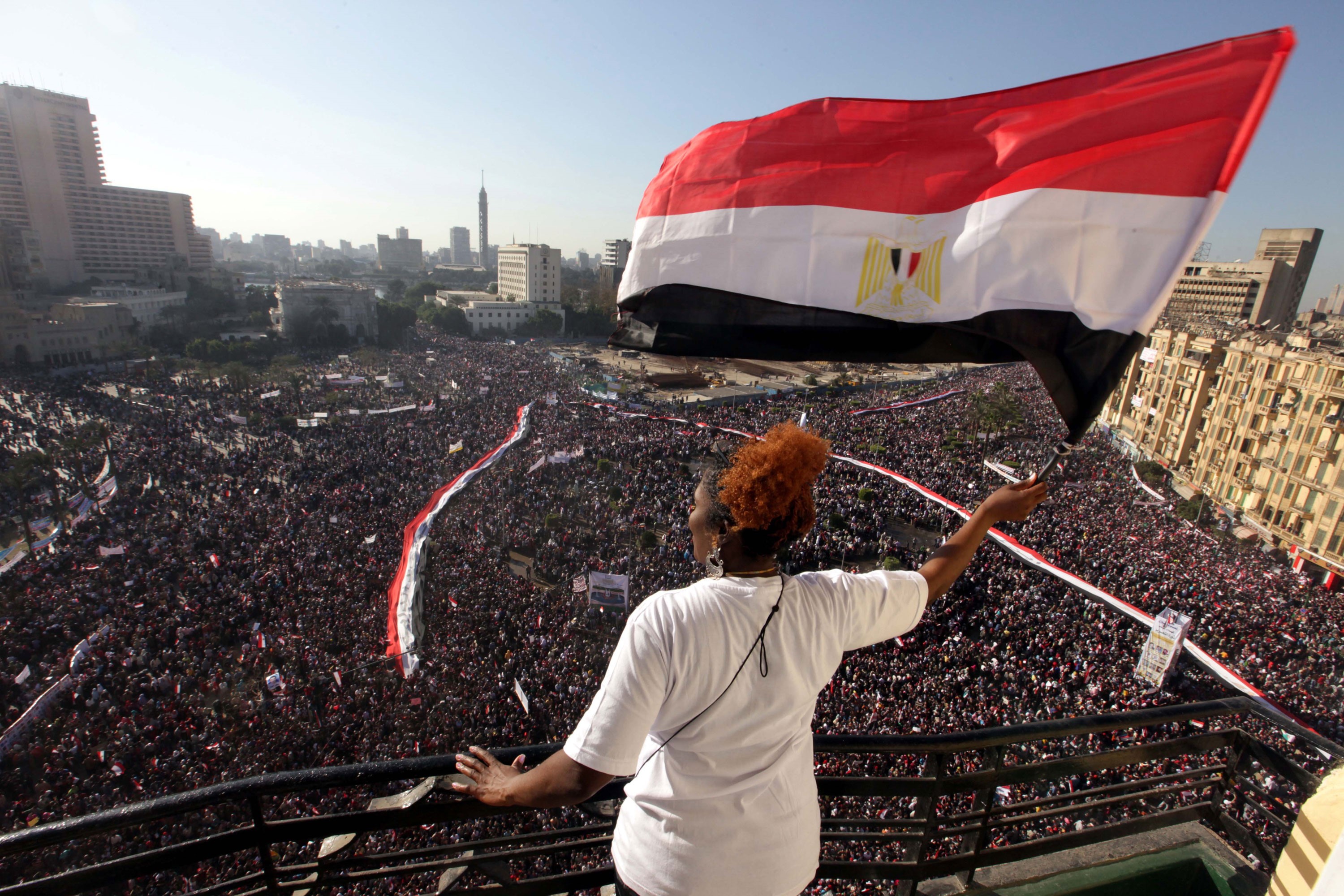

As the military’s chief-of-staff and minister of defense, Major-General Abu Bakr Yunis Jaber was, until recently, one of the most powerful men in Libya. However, he appears to have been detained by Qaddafi after refusing to carry out orders for brutal repression of protesters in Libya’s cities (al-Hurra, February 21). Major Abdel-Moneim al-Huni, Libya’s most recent representative to the Arab League, issued a statement on February 22 on behalf of the “Leadership Council of the Libyan Revolution,” demanding that General Abu Bakr Yunis be released to lead an interim government. Apparently intending to emulate the Egyptian model, al-Huni also appealed to serving officers and troops to abandon the regime: “You who know the honor of military service, I urge you to uproot this regime and take over power in order to end the bloodshed and maintain Libya’s strategic interests and the unity of its land and people.” He further described the use of mercenaries as the regime “signing its own death certificate” (Ahram Online, February 22).

Qaddafi relies heavily on two generals from his own tribe, Sayed Qaddaf al-Dam and Ahmad Qaddaf al-Dam. Sayed is the military head of Cyrenaica, which has come largely under the control of protesters, while Ahmad is the “Guide’s” point-man on Egyptian issues. Aside from Qaddafi and General Abu Bakr, Generals Mustapha Kharoubi and Khouildi Hamidi are the last active members of the 12-man 1969 Revolutionary Council, though both have been reduced to performing ceremonial roles.

A Question of Loyalty

Experiments in Green Book-inspired Jamahiriyah (“popular state”) governance and unification with other Arab/African regimes may have worked against the development of a national identity. Loyalty to the Qaddafis also appears to be shallow; in eastern Libya the police are reported to have helped apprehend a number of mercenaries, while senior military officers are reported to have resigned in Benghazi and Sirte (France24.com, February 21).

There have been many reports of low-paid conscripts and even their officers joining the ranks of the protesters in Benghazi, Darna and elsewhere (Telegraph, February 20). While the al-Fadhil Brigade in Benghazi appears to have gone over to the protestors after their headquarters was set on fire, there are reports that the al-Sibyl Brigade continues to be loyal (al-Jazeera, February 20). Benghazi police are reported to have defected to the protestors after witnessing the methods of the mercenaries (AP, February 21).

Officials in Malta were surprised by two Libyan Air Force colonels who flew their Mirage F1 warplanes from Libya’s Okba Ben Nafi airbase to Malta. The pilots said they flew low to evade radar detection and decided to come to Malta rather than carry out orders to bomb civilians. The Maltese military was also reported to be monitoring a Libyan warship said to be carrying defecting Libyan officers (Times of Malta, February 21, February 22).

Conclusion

Though some Libyans might have been persuaded to desist by the regime’s warnings of disaster and promises of imminent decentralization, organizational restructuring and the dismissal of many state officials, the introduction of mercenaries with orders to kill in the streets of Libya’s cities seems likely to be the last straw before the collapse of the Qaddafi regime. Mercenaries from all quarters have frequently found work defending unpopular African regimes, but at best they have usually only prolonged the inevitable, their very presence an indication that a regime rules only through force rather than popular consensus, regardless of protests to the contrary.

Ironically, it was Qaddafi himself who warned a gathering of Libyan security officials in Tripoli in 2004 to beware of infiltration efforts by “mercenaries, lunatics, infidels and people who pose a threat to security” (Great Jamahiriyah TV, April 14, 2004).

Notes:

1. See GF Abbott, The Holy War in Tripoli, 1912, pp.79-80.

2. See J. Millard Burr and Robert O. Collins, Darfur: The Long Road to Disaster, Princeton N.J., 2008, p. 84.

3. www.youtube.com/watch; www.youtube.com/watch.

4. www.youtube.com/watch.

5. www.generaldynamics.uk.com/news/gduk-secures-new-export-opportunity.