Andrew McGregor

May 30, 2013

A potentially explosive situation in Egypt’s volatile Sinai Peninsula appears to have been averted with the May 22 release of seven members of Egypt’s military and security forces after a six-day abduction by what is believed to be an armed Islamist faction. The circumstances of the release remain unclear and have fostered a variety of claims and accusations.

The kidnappers were identified as members of Tawhid wa’l-Jihad by Shaykh Nabil Na’im, a leading member of the Egyptian Jihad organization and former associate of Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri. Shaykh Nabil was freed during the Egyptian Revolution after two decades in prison (al-Sharq al-Awsat, May 23). According to Shaykh Nabil, Tawhid wa’l-Jihad’s denial of involvement was “a deception” designed to avoid a military campaign against the movement. Noting that Tawhid wa’l-Jihad has aligned itself with al-Qaeda, Shaykh Nabil suggests that al-Qaeda serves Israeli objectives “in an ignorant and foolish way” that promotes an alleged Israeli plan to resettle Gazans in the Sinai: “At present, the West and Israel look at Sinai as a land that has no owner in which al-Qaeda is running wild, and this is something dangerous.” The shaykh described Tawhid wa’l-Jihad as a takfiri organization (one that declares Muslims who oppose its agenda to be apostates): “They are ignorant about the Islamic Shari’a – we have lived with them and know them well.”

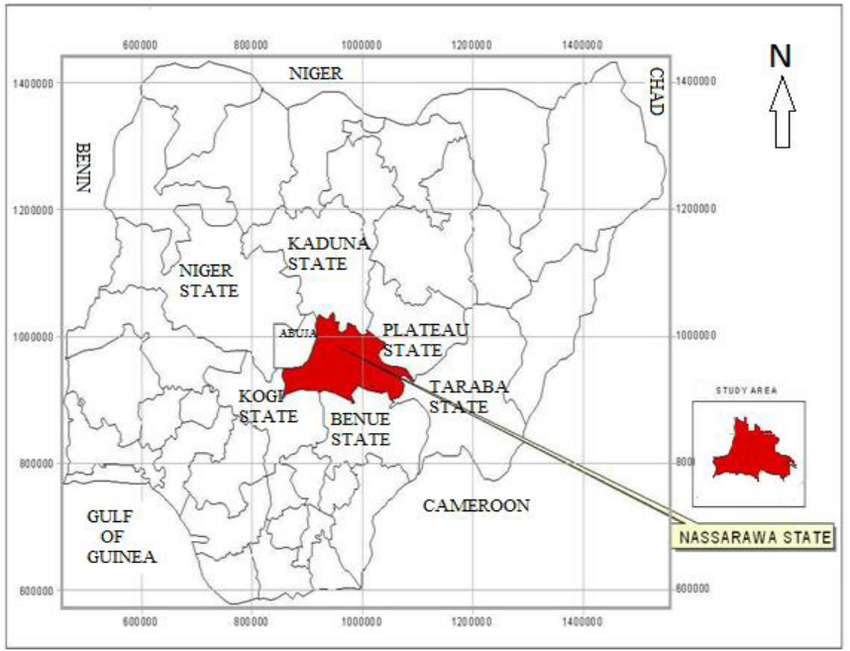

Egyptian Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim confirmed that the kidnapping was part of an effort to obtain the freedom of Shaykh Hamadah Abu Shita, a leader of Tawhid wa’l-Jihad who was reported to have been tortured in Turah Prison after attacking a prison guard (MENA, May 21; Ahram Online, May 23). The kidnappers were also alleged to have demanded the release of a number of prisoners being held at the police station in the North Sinai town of al-Arish (MENA, May 22). The search for the hostages prompted a major military incursion into the politically sensitive Sinai – aside from ground and aerial security sweeps over the North Sinai, Egyptian troops were deployed in large numbers in the capital of al-Arish, the town of Shaykh Zuwayid and the border town of Rafah (MENA, May 21).

The kidnapping proved unpopular with most parties active in the Sinai, including North Sinai’s tribal chieftains, who called for the immediate discovery and arrest of those responsible (MENA, May 25). Not all the Sinai Salafists were content with the kidnapping; the Ahl al-Sunna wa’l-Jama’a group condemned the action (MENA, May 22). Cairo’s al-Azhar University, the world’s leading center of Islamic studies, issued a statement describing the abductions as a contradiction of the teachings of Islam and a violation of internationally understood norms of personal freedom (MENA, May 20). According to Shaykh Muhammad Adli, “Everybody was searching for the soldiers, even Salafist Jihadists. Everybody condemned this act… If the soldiers had not been released, a war would have flared up in the area” (Dream 2 Satellite Television [Cairo], May 25).

Various theories were advanced to explain the incident and its resolution; one such, attributed to secular sources, suggested that Gaza’s HAMAS had engineered the entire abduction and then deliberately yielded to President Muhammad Mursi’s delegation without a shot fired in order to make the Egyptian president look good (Xinhua, May 22; Egyptwindow, May 25). Reports from the Sinai that Mursi had played no role in liberating the hostages contrasted with claims the president had agreed to release a certain number of prisoners in exchange for the release of the hostages (Amal al-Ummah [Alexandria], May 23). Some of the detainees were said to have been in custody for four years without charge. A military source told a Cairo daily that it was the tribal leaders who convinced the kidnappers to release their captives, partly because they sympathized with the kidnappers’ cause, if not their actions: “Tribal leaders coordinated with military intelligence. They refused to cover for the kidnappers and informed them that they will not support them” (Ahram Online, May 22).

The main mediator in the negotiations has been identified as Shaykh Muhammad Adli, a renowned Egyptian qari (one who recites the Quran from memory) with experience in mediating problems in the Sinai. Adli reported his help was requested by the kidnappers, who were willing to release the hostages but feared being attacked during the handover. The shaykh praised the efforts of the commander of the Second Field Army, Major General Ahmad Wasfi, and contrasted the more patient approach of the security forces with their reaction to the 2004 bombing of a Sinai resort, when “everybody was arrested and tortured, including me” (Dream 2 Satellite Television [Cairo], May 25).

HAMAS denied any role in the abductions and said the movement has become a subject of suspicion in Egypt due to an Israeli proposal to resettle Gazans in the Sinai, a proposal that has failed to find support in the Palestinian population. Dr. Musa Abu-Marzuq, a senior HAMAS member, noted that the movement has no interest in antagonizing Egypt: “The Gaza Strip and HAMAS are not a superpower that puts itself on an equal footing with Egypt” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, May 22).

In some quarters, suspicion of responsibility for the abductions fell on Palestinian Fatah strongman Muhammad Dahlan (a.k.a. Abu Fadi), a bitter enemy of HAMAS who has been accused by many Palestinians of corruption and collaboration with Israeli intelligence services. HAMAS claims to have obtained confessions from a number of Dahlan’s supporters implicating the Fatah leader in organizing the kidnappings to advance a three-fold agenda involving the creation of instability in Sinai to benefit Israeli interests in the region, the provocation of confrontations between the Egyptian army and Sinai-based jihadi groups and an attack on the reputation of HAMAS that would complicate its relations with Cairo (al-Akhbar [Cairo], May 27).

Dr. Essam Muhammad Hussein al-Erian, the vice-chairman of the Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing, the Hizb al-Hurriya wa’l-Adala (Freedom and Justice Party), accused Dahlan of playing a role in the abductions through Dahlan’s deployment of over 500 gunmen in the Sinai with financing from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which has accused the Muslim Brotherhood of attempting to create a cell in the UAE dedicated to the overthrow of the UAE government (al-Hayat, May 25). Dahlan responded by accusing the Muslim Brothers of acting as the agents of the United States and Israel: “This is not the first time the rumor-mongering bats of the Muslim Brotherhood circulate lies and illusions to cover up their failure and crimes of their militant gangs against Egypt and Palestine… You have been the genuine allies and loyal associates of the U.S. and Israel. Your lies no longer fool anyone” (Ahram Online [Cairo], May 27).

According to a Salafist source within the Sinai who was involved in the negotiations, the presidential delegation failed in its efforts before military intelligence negotiated an end to the hostage-taking without making any specific deals (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], May 26). Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim insists that no negotiations were conducted with the kidnappers, though he acknowledged the efforts of tribal chieftains in helping avoid a military operation against the abductors (MENA, May 21). Despite this, tribal leaders were still angered that they were left out of the final resolution and were unable to obtain the identities of the kidnappers from the security forces. According to Naim Gabr, head of the Coalition of Sinai Tribes, “If security authorities don’t inform us of what happened, we will convene a meeting of all tribes to mull a joint response… If the intelligence apparatus and military lose the tribes’ trust, the consequences for Sinai – and Egypt’s national security in general – will be dire” (Ahram Online, May 26).

For some Egyptians, the quiet resolution to the abductions leaves too many unanswered questions. After a government statement said the identities of the abductors was known to the Interior Ministry, it is difficult for many Egyptians to understand why no arrests have been made, especially when the government continues to maintain that no deal was made for the release of the hostages. To combat the growing Islamist militancy in the Sinai, President Mursi has ordered the Ministry of Religious Endowments (awqaf) to send moderate preachers and well-known imams to Sinai to challenge the religious extremism of the jihadis (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], May 26).

President Mursi has publicly urged his security chiefs to finish their counter-terrorist operations in the Sinai before returning to base and General Wasfi has pledged that the Army will remain in the Sinai until it restores law and order to the region (MENA, May 23). There are, however, suspicions that the army will draw down sooner rather than later to permit the President to avoid alienating Salafist politicians who are sympathetic to the aims of Islamist factions operating in Sinai.

This article first appeared in the May 30, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor