Andrew McGregor

May 30, 2015

While the success of Somali government and African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) offensives against al-Shabaab insurgent formations in central and southern Somalia is welcome, it has unfortunately resulted in the migration of beleaguered al-Shabaab fighters to the northern Somalia region of Puntland, an area offering superb refuges in rough terrain with only a lightly-armed paramilitary to defend the region, which has only been lightly touched until the last year by the fighting with al-Shabaab in the rest of Somalia.

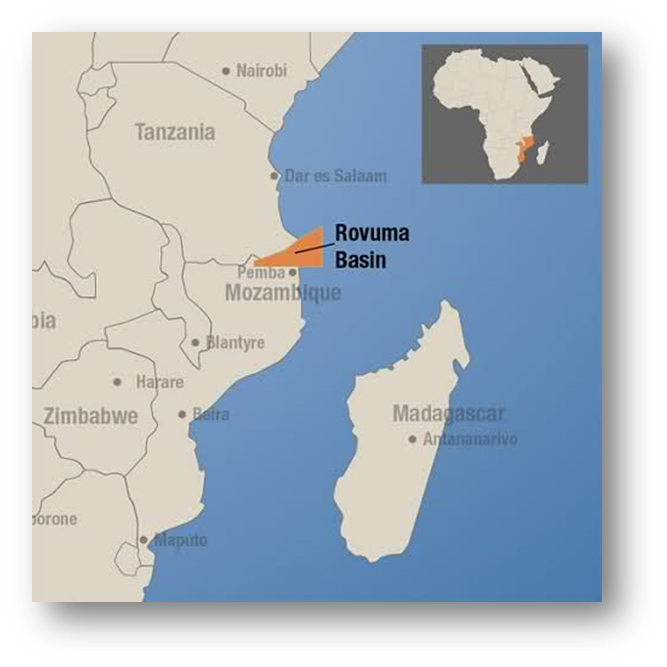

Puntland emerged as an autonomous region in 1998 in an effort to separate the largely peaceful north from the political chaos consuming central and southern Somalia at the time. Though it acts largely independently of the central government in Mogadishu, Puntland is normally a strong supporter of a federal Somali state with many powers devolved to regional administrations. The region has a population of roughly 4 million, at least half of whom continue to pursue nomadic lifestyles.

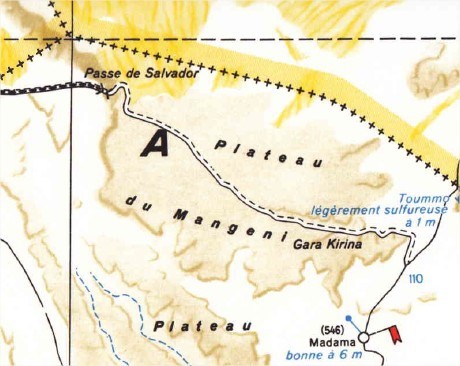

Al-Shabaab fighters have been reported pouring into the Galgala Hills, a remote region of Puntland 50 kilometers east of Bossaso (Puntland’s major port and commercial center) that has been the subject of a struggle for control between the Majerteen and Warsangali clans. The region was cleared of Shabaab-sympathetic insurgents with great effort last year but remains attractive to al-Shabaab as it sits outside the mandated range of African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) operations in Somalia, though a UN spokesman has promised the organization is considering an expansion of its operational area (Reuters, May 7).

In the meantime, al-Shabaab maintains a persistent presence in the rocky hill country After a week of heavy fighting in January, Puntland’s security authorities announced the capture of the last al-Shabaab camp in the Galgala region, the death of 20 militants and the capture of two al-Shabaab commanders (Horseed Media, January 7, 2015). Yet a little more than a month later, authorities were announcing a successful battle in the same region that killed 16 al-Shabaab militants (Horseed Media, February 14, 2015; Garowe Online, February 14, 2015). Al-Shabaab gunmen and terrorists are using the hills as a base for attacks on Bossaso and, more recently, the Puntland capital of Garowe:

- On February 7, al-Shabaab gunmen in four cars attacked a military post in Bossaso, sparking a three-hour gunfight that left a number of terrorists and security personnel dead (Horseed Media, February 8, 2015).

- On April 5, gunmen attacked a security checkpoint near the Hotell Yasmin in the heart of Bossaso. Two militants and a soldier were killed (Somaliland Sun, April 6).

- On April 18, three al-Shabaab fighters attacked the Balade police station in Bossaso with RPGs. It was the second such assault on the Balade station in two months (Garowe Online, April 18, 2015).

- On April 20, a suicide bombing on a UNICEF vehicle killed four foreign UNICEF workers and two Somali security guards while sending a further six (including an American) to a Garowe hospital. It was the first such attack in Garowe, which is otherwise enjoying a wave of development. Following the attack, al-Shabaab spokesman Ali Mohamud Rageh vowed that his movement would continue its strikes against US agencies, accusing the UN of facilitating the “invasion” of Somalia and promising UN staff would “taste our bullets” (Horseed Media, April 23, 2015).

- On May 5, al-Shabaab claimed responsibility for a grenade-tossing attack on a police post in the port of Bossaso and a larger attack using RPGs and heavy machineguns against another police post at Yalho on the outskirts of Bossaso (Horseed Media, May 5, 2015). The latter post was briefly taken and three policemen killed before security forces retook it in a counterattack (Reuters, May 5, 2015).

Members of Puntland’s parliament have also been targeted in a broader campaign of assassinations similar to those carried out previously by al-Shabaab in southern Somalia. MP Adan Haji Hussein was killed in April while the latest such death was that of MP Saeed Nur Dirir, a close ally of Puntland’s president, Abdiweli Mohamed Ali ”Gaas” (Garowe Online, May 8, 2015).

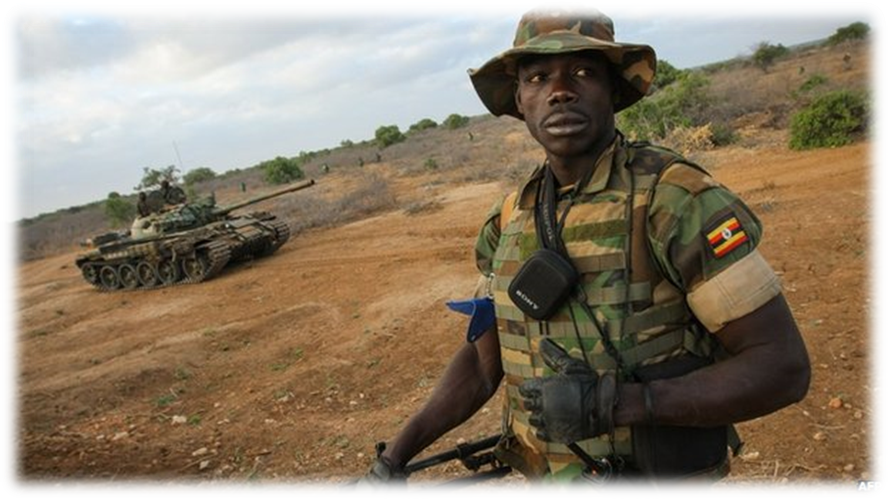

Armed Federalism: Troops of the Puntland Defense Force on Patrol in Mogadishu

Armed Federalism: Troops of the Puntland Defense Force on Patrol in Mogadishu

The political chaos in Yemen, a short distance from Puntland, is also complicating Puntland’s security situation, with refugees, arms, escaped prisoners and possibly even fighters making the short trip by boat across the Gulf of Aden to Puntland. Some 2,000 refugees have arrived in northern Somalia so far, though UN experts expect as many as 100,000 more in the next few months, a number that simply cannot be accommodated by northern Somalia’s meagre resources. Beside fears that militants might use the exodus to infiltrate Somalia, the fighting in Yemen has collapsed markets for Puntland goods there, including markets for the all-important fish industry (Raxanreeb, April 19, 2015).

Puntland authorities have lately the appearance of using a firm hand in dealing with al-Shabaab terrorists – in mid-March, three men suspected of planning and carrying out terrorist attacks in Puntland were executed by firing squad only days after a quick trial (Horseed Media, March 16, 2015). According to sources in Puntland, the three were among dozens of al-Shabaab suspects who have been handed death penalties, life imprisonment or lesser terms (Garowe Online, March 16, 2015). However, a report by the UN’s Monitoring Group on Eritrea and Somalia issued last October raised serious questions regarding the determination of the Puntland regime to address the al-Shabaab threat. The report notes the impediments thrown up by the administration (particularly the office of the president) to UN efforts to investigate the growth in al-Shabaab activity in Puntland, suggesting that this “is indicative of its unwillingness to robustly address the threat of al-Shabaab.”[1] The report further suggested the government of President Abdiweli Mohamed Ali had adopted a “catch and release” policy respecting al-Shabaab suspects, allowed the infiltration of its security services and had even intervened in the prosecution and detention of al-Shabaab members.[2]

On February 22, deputy commander-in-chief of police Mohiyadin Ahmed Aw-Musse was sacked by the Puntland president after expressing his fury with the quick release of al-Shabaab members collected in a security sweep, some of whom were allegedly freed by presidential decree. Having been the target of al-Shabaab assassins only two weeks before in an attack that killed two of his bodyguards, Aw-Musse’s displeasure with such policies was understandable. Puntland Intelligence Agency (PIA) director Abdi Hassan Hussein was also fired on February 22 (Garowe Online, February 22, 2015).

Most of the counter-terrorism work in Puntland is handled by the American-trained Puntland Intelligence Agency (PIA), formerly the Puntland Intelligence Service (PIS). Puntland also relies on a frontier paramilitary of roughly 7,000 men known as the Puntland Dervish Force, some of whom have received training in Uganda. Regular payment of security forces remains a problem, leading to frequent strikes by police and troops (Garowe Online, January 26, 2015). Despite these problems, Puntland has agreed to commit 3,000 of its troops to the growing Somali National Army (Reuters, May 7, 2015).

Puntland Security Forces in the Galgala Hills

Puntland Security Forces in the Galgala Hills

Some of the arms used by al-Shabaab appear to be imported through the Berbera port in neighboring Somaliland (a self-declared but unrecognized independent state), a traffic that Somaliland officials claim to be trying to stop, though Puntland officials routinely accuse Somaliland (with whom they are engaged in a bitter and long-standing territorial dispute in the Sanoog-Sool-Cayn region) of supporting al-Shabaab (Raxanreeb, January 30, 2015). Though several top al-Shabaab leaders have hailed from Somaliland in recent years, no evidence has been produced that these leaders have or had any connection to Somaliland authorities. According to the chairman of Kulmiye, the ruling party in Somaliland, Puntland accuses Somaliland of supporting terrorism “only to conceal its [own] security failures” (Somaliland Sun, February 21, 2015).

PROJECTIONS

The obsession of Puntland’s authorities with Somaliland hinders the development of accurate intelligence regarding al-Shabaab’s true aims and activities, while accusing Somaliland of backing al-Shabaab prevents the resolution of the territorial dispute between the neighboring administrations. Puntland intelligence assessments tend to be heavily clouded by dislike of the Somaliland leadership.

Bossaso, due to its importance as a port with connections to Yemen and its proximity to militant bases in the Galgala Hills, will continue to experience a high degree of insecurity until superior military forces can undertake clearing operations in the region while securing entry points, a considerable but not unsurmountable task with some foreign logistical, surveillance and intelligence assistance. If al-Shabaab’s shift north is to be halted, close cooperation will be required between the security forces of Mogadishu and Garowe, cooperation that is threatened by yet another territorial dispute in Puntland’s southern Mudug region, where authorities are working to form a new federal state in combination with the neighboring Galgudud region (a stronghold of the Sufi militia Ahlu Sunnah wa’l-Jama’a), a process strongly opposed by the Puntland government and even by many residents of the Mudug region.

Notes

[1] United Nations Security Council, Letter dated 10 October 2014 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992)and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea addressed to the President of the Security Council. October 13, 2014, http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2014_726.pdf

[2] Ibid, pp. 69-74.