Andrew McGregor

March 21, 2013

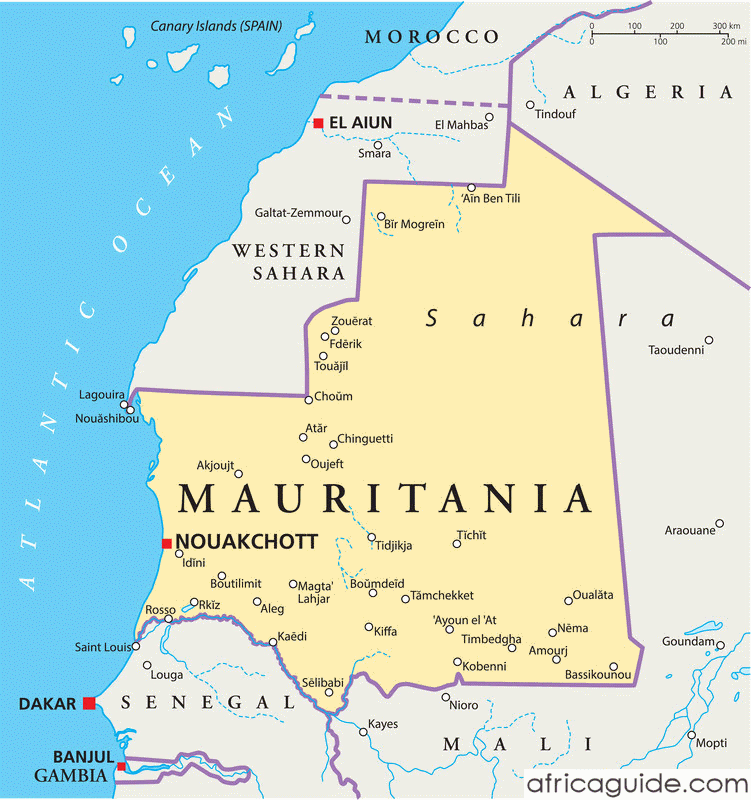

The largely desert nation of Mauritania has been engaged in an often deadly struggle against al-Qaeda terrorists and local Salafist militants for several years now. Many local Salafists now populate the prison in the capital of Nouakchott, though even this does not seem to have deterred some of them from carrying out various activities.

Abu Ayyub al-Mahdi (a.k.a. Ahmad Salim bin al-Hassan), an imprisoned Mauritanian Salafist, announced the creation of a new militant group, Ansar al-Shari’a in the Shanqiti [Mauritanian] Country, on February 12, the latest in a series of autonomous but ideologically sympathetic Ansar al-Shari’a groups to spring up across North Africa and the Middle East.

Abu Ayyub al-Mahdi (a.k.a. Ahmad Salim bin al-Hassan), an imprisoned Mauritanian Salafist, announced the creation of a new militant group, Ansar al-Shari’a in the Shanqiti [Mauritanian] Country, on February 12, the latest in a series of autonomous but ideologically sympathetic Ansar al-Shari’a groups to spring up across North Africa and the Middle East.

One of the greatest promoters of the Ansar al-Shari’a phenomenon is a Mauritanian ideologue, Abu Mundhir al-Shanqiti, the author of an influential 2012 article entitled “We are Ansar al-Shari’a.” [1] Al-Shanqiti proposed gathering the disparate Salafist-Jihadist movement behind a unified objective – the rejection of democracy and the establishment of Shari’a as the leading principle in the Muslim world. As part of this process, al-Shanqiti maintains the movement must be brought out into the open from its present underground existence (al-Hayat, January 3). This may be a difficult task however; many of the Salafists detained in the Nouakchott prison have denied any association with the new branch of Ansar al-Shari’a (Al-Monitor, February 19).

Though President Muhammad Ould Abd al-Aziz kept Mauritanian forces out of the current ECOWAS-based African intervention force operating in Mali on the grounds that Mauritania was not an ECOWAS country and that the French-led intervention was launched without prior notice, he has indicated that Mauritania would be ready to provide troops to a UN-backed mission in Mali. The president added that Mauritania is aware of two problems driving the insecurity in Mali, these being Bamako’s tolerance of terrorist groups in northern Mali over the last 12 years and the “sometimes legitimate” demands of the people of northern Mali for “basic infrastructure, health and education” (Sahara Media [Nouakchott], March 4).

Mauritanian military intervention in Mali is opposed not only by the Salafist community, but also by mainstream, secular politicians such as Ahmad Ould Daddah, the main opposition leader and secretary general of the Regroupement des Forces Démocratiques (RFD – Rally of Democratic Forces):

I am afraid we will participate in a war that we have no interest in — a war that poses danger to us and the region in general. What our region and the Sahel region need are building and development efforts to improve conditions; not the destruction of an already worn-out infrastructure… We do not want or accept that our region becomes the Afghanistan of the African Sahel. To remove any confusion, we affirm that we are against terrorists and terrorism. However, each war has two fronts; a fighting front and an internal front, which is more important than the fighting front in my opinion. When the national public opinion is not convinced of the reasons and pretexts of a war, it means that it does not serve the country. This affects the performance of the soldiers and makes them question the sanctity of their mission (al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 11).

Ould Dadah initially supported Ould Abd al-Aziz, but now observes the president backing away from democracy to adopt a more military-style of rule and notes the adverse effects on military performance created by involving the military in politics, effects that could hamper the military’s ability to mount a campaign in Mali or even effectively guard its 2,237 kilometer border with that country:

We have become certain that he adheres to the mentality of a military rule, which is not proper in for a country that claims to be democratic. The practices of the regime encourage the army to become involved in politics, abandon its noble military mission, and to indulge in luxuries that destroy its combat ability. In my opinion, the army is the first to be harmed by the military regime. It is also dangerous when the army becomes involved in politics, because in this case politics are practiced through guns and weapons, not through reason, thinking, and logic. This is the logic of the military rule that is running the country (al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 11).

In Mauritania, 3.5 million people live in a land of well over 1 million square kilometers. Mauritania’s security services lack the men and resources to properly patrol and monitor the nation’s borders, most of which cross lifeless deserts. This has left Mauritania open to attack by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) several times in the past, despite efforts to set up joint counter-terrorist patrols with the similarly under-equipped Malian army (see Terrorism Monitor July 7, 2011; November 11, 2010). On March 17, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced the capture of five “Islamist terrorists” from northern Mali who were caught trying to infiltrate the border (Agence Nouakchott d’Information, March 18).

In early February, Mauritania launched a new initiative with its southern neighbor, Senegal, to coordinate military activity along the border with groups of villagers along the Senegal River who will act as the eyes and ears of the security services in identifying suspicious individuals or groups active in the border region (Al-Monitor, February 6). Senegalese troops recently arrested a Mauritanian al-Qaeda member who had slipped into the country across the border (PANA Online {Dakar], February 15). Mauritania is now hosting more than 150,000 refugees from northern Mali and claims to have intercepted several al-Qaeda militants posing as part of that number.

There are extensive historical and communal ties between the two countries – many of the Arab tribes of northern Mali have relatives across the border in Mauritania, while a significant number of Mauritanians have settled in northern Mali over the years. There have been repeated demonstrations in the Mauritanian capital of Nouakchott by Malian Arab refugees protesting human rights abuses by Malian troops following the French intervention force into northern Mali (RFI, March 12; AFP, March 11).

Mauritania hosted this year’s Operation Flintlock, an annual training exercise for North African and West African militaries sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Africa Command (AFRICOM). The exercises, which ended on March 9, saw troops from the United States and various NATO allies provide training in counter-terrorist operations and field-craft. Last year’s exercises, which were to be held in Mali, were cancelled due to the Islamist occupation of Mali’s northern districts. Some of the African troops trained in this year’s event could wind up taking part in a possible UN peacekeeping operation in northern Mali.

This article first appeared in the March 21, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.