Andrew McGregor

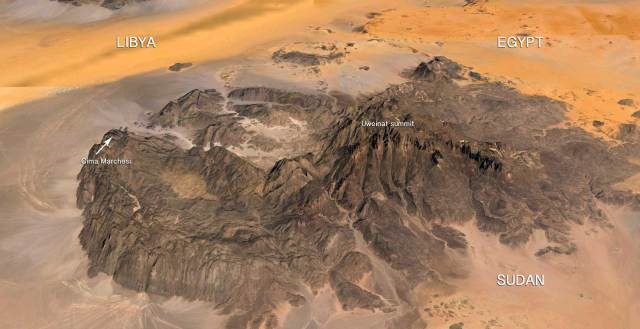

AIS Special Report, June 13, 2017 Before the advent of motorized desert exploration in the 1930s there were few areas as little known as the Libyan Desert, a vast and largely lifeless wasteland of sand and stone as large as India. In the midst of this forbidden wilderness stands a lonely sentinel, a massive mountain that covers some 600 square miles and rises to a height of 6345 feet, once possibly forming an island in the prehistoric sea that preceded the Saharan sands. Though its springs and rain-pools were known to the Ancient Egyptians, Jabal ‘Uwaynat was eventually forgotten for thousands of years by all but a handful of hardened desert dwellers who sought its fresh water and seasonal grazing. Since its “rediscovery” less than a hundred years ago, possession of this lonely massif has almost led to a war between Italy and Great Britain and is now at the heart of a security crisis involving Libya, Egypt and Sudan, whose borders meet at Jabal ‘Uwaynat.

Before the advent of motorized desert exploration in the 1930s there were few areas as little known as the Libyan Desert, a vast and largely lifeless wasteland of sand and stone as large as India. In the midst of this forbidden wilderness stands a lonely sentinel, a massive mountain that covers some 600 square miles and rises to a height of 6345 feet, once possibly forming an island in the prehistoric sea that preceded the Saharan sands. Though its springs and rain-pools were known to the Ancient Egyptians, Jabal ‘Uwaynat was eventually forgotten for thousands of years by all but a handful of hardened desert dwellers who sought its fresh water and seasonal grazing. Since its “rediscovery” less than a hundred years ago, possession of this lonely massif has almost led to a war between Italy and Great Britain and is now at the heart of a security crisis involving Libya, Egypt and Sudan, whose borders meet at Jabal ‘Uwaynat. The Highway to Yam

The Highway to Yam

The ancient importance of Jabal ‘Uwaynat is revealed in the rock art at the site depicting cattle, giraffes, lions and human beings, but no camels, which were only introduced into Egypt in roughly 500 BCE. The drawings suggest an occupation in the Neolithic period far earlier than the era of the Ancient Egyptians at a time when water was far more plentiful in the region. [1]

The Inscription of Mentuhotep II at Jabal ‘Uwaynat

The Inscription of Mentuhotep II at Jabal ‘Uwaynat

Though ‘Uwaynat was long believed to lie beyond the regions explored by the Ancient Egyptians, the remarkable 2007 discovery of a depiction of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom king Mentuhotep II (11th Dynasty, 21st century BCE) promises to rewrite these perceptions. The portrayal of the seated king was accompanied by his name in a cartouche and an inscription mentioning the land of Yam, known as a destination for Egyptian trade caravans supplying exotic goods from the African interior from as early as the Old Kingdom reign of Merenre I (6th Dynasty, 23rd century BCE). [2] The exact location of Yam has never been determined, but the new evidence suggests it was somewhere south of ‘Uwaynat and further west into the African interior than previously thought by many scholars, possibly in Ennedi (modern Chad) or even Darfur (modern Sudan). The precise site of the inscription has been kept secret to avoid the ravages of “adventure tourism” that has led to the damage or destruction of many important Saharan monuments and rock art sites in recent years. [3]

Entering the Modern Era

The great mountain disappeared from the historical record until the early 19th century, when, according to English desert explorer Ralph Bagnold, an Arab from the Libyan oasis of Jalu and a resident at the court of Sultan Muhammad ‘Abd al-Karim Sabun of Wadai (1804-1815, modern eastern Chad), undertook to find a new trade route northwards through the Libyan Desert to Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast. The experienced Arab caravan leader, Shehaymah, headed northeast first to the remote springs at Jabal ‘Uwaynat, then worked northwest to Kufra and on through Jalu to Benghazi. [4] The fact that Shehaymah headed into this unknown wasteland suggested that he had some prior knowledge of ‘Uwaynat. Though this route was used by the Shehaymah and the Wadaians only once, this was the first known reference to the isolated mountain. From that time, caravan routes from Wadai bypassed ‘Uwaynat to the west on a more direct route north to the coast, while the famous Darb al-Arba’in caravan route from Darfur to Asyut in Egypt bypassed ‘Uwaynat far to the east, letting knowledge of ‘Uwaynat’s existence fade from all save the Tubu tribesmen of the eastern Sahara whose mastery of the desert and its mysteries was unparalleled.

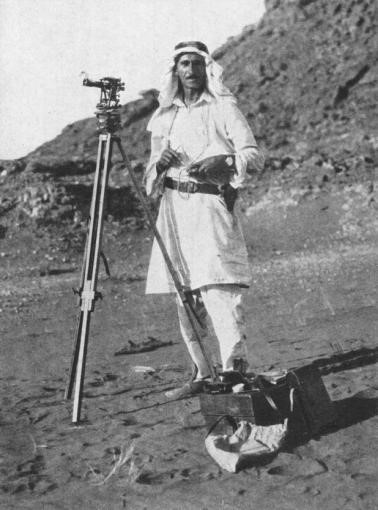

Nearly 3,000 years after its last known visit by the Egyptians, Jabal ‘Uwaynat was finally mapped by another Egyptian, the aristocrat Ahmad Muhammad Hassanein Bey, who “discovered” this “lost oasis” during an extraordinary 2200 mile trek by camel from the Mediterranean port of Sollum (near the Egyptian/Libyan border) to al-Fashir, the capital of Darfur. At the time of Hassanein Bey’s arrival, the mountain was the site of a settlement of some 150 Gura’an Tubu from Ennedi, relatively recent arrivals who did not wish to live under the rule of the French who had recently colonized the Chad region up to the Darfur border. Seven years later, only six remained; three years after that, the Gura’an settlement had disappeared forever. [5]

Two years after Hassanein Bey’s visit, Prince Kamal al-Din Hussein (son of Egypt’s Sultan Husayn Kamel, 1914-1917) visited ‘Uwaynat in a remarkable expedition using French Citröen Kegresse halftracks, supported by immense camel-borne supply convoys. This well-financed motorized journey by halftracks, as temperamental as camels in their own way, marked the beginning of the end of ‘Uwaynat’s ancient isolation.

The legendary English desert explorer Ralph Bagnold reached ‘Uwaynat by motorcar in 1930, inventing the techniques of desert-driving in the process. His atmospheric description of the place is still worth citing:

The legendary English desert explorer Ralph Bagnold reached ‘Uwaynat by motorcar in 1930, inventing the techniques of desert-driving in the process. His atmospheric description of the place is still worth citing:

[‘Uwaynat] was by no means the flat-topped plateau it had looked from the plain; for the rock was hollowed out by a freak of erosion into spires and pinnacles over a hundred feet in height, separated by winding passages… Wandering through this labyrinth, we came out at unexpected places to the threshold, as it were, of a broken doorway high up in the battlements of some ruined castle, with nothing but a sheer thousand-foot drop beneath. From these openings the enormous yellow plain could be seen, featureless and glaring with reflected sunlight, reaching away and away in all directions (except to the south, where the peak of Kissu many miles distant rose like a lone cathedral) to a vague hazy horizon… With that little vision came a sudden overwhelming sense of the remoteness of the mountain – as if it included the whole world and was floating by itself, with Kissu peak as its satellite, in a timeless solitude. [6]

In 1931 an Italian expeditionary force under General Rodolfo Graziani crossed the desert to take the oasis of Kufra (northwest of ‘Uwaynat), where they defeated a desperate resistance put up by the Zuwaya Arabs. Unsatisfied with his conquest, Graziani (“the Butcher of Libya”) urged his men to pursue the survivors into the desert, attacking refugee families with armored vehicles and aircraft. Many of the refugees headed towards ‘Uwaynat, dropping dead daily in large numbers due to lack of food and water. Not knowing the region, some tried to follow the tracks of Prince Kamal’s halftracks, but when these became obliterated by sand and wind there was little hope left. Many of the refugees were rescued by British desert explorer Pat Clayton, who abandoned his survey work in the region to cover some 5,000 total miles of desert in his vehicles ferrying exhausted and dying refugees to safety. His efforts earned him a British medal and a ban from Italian-held Libya.

In 1931 an Italian expeditionary force under General Rodolfo Graziani crossed the desert to take the oasis of Kufra (northwest of ‘Uwaynat), where they defeated a desperate resistance put up by the Zuwaya Arabs. Unsatisfied with his conquest, Graziani (“the Butcher of Libya”) urged his men to pursue the survivors into the desert, attacking refugee families with armored vehicles and aircraft. Many of the refugees headed towards ‘Uwaynat, dropping dead daily in large numbers due to lack of food and water. Not knowing the region, some tried to follow the tracks of Prince Kamal’s halftracks, but when these became obliterated by sand and wind there was little hope left. Many of the refugees were rescued by British desert explorer Pat Clayton, who abandoned his survey work in the region to cover some 5,000 total miles of desert in his vehicles ferrying exhausted and dying refugees to safety. His efforts earned him a British medal and a ban from Italian-held Libya.

The British-Italian Struggle over ‘Uwaynat

The pursuit of the refugees brought Jabal ‘Uwaynat to the attention of the Italians, who sent expeditions to the mountain in 1931 and 1932 with an eye to claiming it for Italy, though it was already claimed by the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Condominium government. Suddenly this desert massif known to the Europeans for only less than a decade became a site of strategic importance – a base there would bring Italian forces within striking distance of the Aswan Dam (550 miles away) using aircraft or motor vehicles. The Italians busied themselves with naming all the mountain’s prominent features for prominent Italian fascists, but were deeply disappointed to discover Bagnold’s cairn at the highest point of Jabal ‘Uwaynat.

In the meantime, both the Italians and the British in the region remained wary of encountering the deadly but phantom-like Gura’an raiders led by the notorious Aramaï Gongoï. These Tubu raiders could cross hundreds of miles of trackless and apparently waterless deserts on their camels without benefit of any kind of navigational equipment before descending on unsuspecting oases or desert convoys. Mystified by these skills, their oasis-dwelling victims even claimed the Gura’an camels left no tracks in the sand.

The British and Italians began sending aircraft and patrols to ‘Uwaynat and by 1933 it seemed, incredibly, that Britain and Italy could go to war over possession of a remote place only a select few had ever seen or heard of until that point. Saner heads prevailed in 1934 as diplomats defined the border, giving Italy (and later independent Libya as a result) sovereignty over much of the mountain (including ‘Ain Dua, the most reliable spring) as well as the “Sarra Triangle” to the southwest of the formation in return for Italy abandoning its claims to a large portion of northwest Sudan. These claims had been based on Italy’s view of itself as the sovereign successor to the Ottoman Empire in the region, the Ottomans having once made optimistic but largely unenforceable claims to large tracts of the Saharan interior in the late 19th century.

What the British Foreign Office had overlooked was that Italy had taken control of the remote but valuable Ma’tan al-Sarra well inside the so-called “Sarra Triangle.” The site for the well was chosen in 1898 by the leader of Cyrenaïca’s Sanussi religious order, Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanussi. Al-Sannusi wished to open a new trade route to equatorial Africa from his headquarters in Kufra, but was hindered by the nearly waterless 400 mile stretch between Kufra and the next major well at Tekro (northern Chad). Al-Sanussi said a prayer at the site, roughly mid-way between Kufra and Tekro, and ordered his followers to dig. Months passed with camel convoys ferrying supplies to the workers until they finally found, at a depth of 192 feet, an apparently unlimited supply of water. [7]

Lying two hundred miles west of ‘Uwaynat, the strategic value of Ma’tan al-Sarra would be realized by Mu’ammar Qaddafi, who used it as a staging point for a group of Sudanese dissidents and followers of Sadiq al-Mahdi (great-grandson of Muhammad al-Mahdi and two-time prime minister of Sudan) to launch a 1976 attack on his enemy President Ja’afar Nimieri in Khartoum. The force passed south of ‘Uwaynat but the coup attempt failed after several days of bloody fighting in the Sudanese capital, followed by a wave of executions of captured dissidents and their supporters.

Qaddafi later used the Ma’tan al-Sarra as a forward airbase in his unsuccessful attempt to seize the Aouzou Strip during the Libya-Chad war of 1978-1987. Chad’s largely Tubu army under Hassan Djamous seized the airbase in a devastating lightning raid on September 5, 1987, bringing an effective end to the war with a humiliating Libyan defeat.

‘Uwaynat in the Second World War

As World War II broke out, possession of ‘Uwaynat was contested between the modified Fords and Chevrolets of the Commonwealth Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), invented and commanded by Major Ralph Bagnold, and their motorized Italian counterparts in the Compagnie Sahariane, a largely Libyan force with Italian officers and NCOs. As the war began, Italian forces established posts at the ‘Uwaynat springs of Ain Zwaya and one at ‘Ain Dua, both equipped with airstrips and garrisoned largely by Libyan colonial troops under Italian command.

After the Italians had been driven from the region by British and Free French offensives, the British-led Sudan Defence Force (SDF) used the route past ‘Uwaynat for regular convoys of arms and supplies to the Free French garrison in Kufra. This oasis had been taken by General Phillippe Leclerc’s Free French forces with the assistance of the British Commonwealth’s Long-Range Desert Group (LRDG) on March 1, 1941. [8]

A Libyan SIAI-Marchetti SF-260

A Libyan SIAI-Marchetti SF-260

When a Libyan National Army-operated SIAI-Marchetti SF.260 light aircraft disappeared in the region in May 2017, it was a reminder that extreme heat and sudden sandstorms can make aerial surveillance of the border region around ‘Uwaynat a perilous undertaking. The aircraft left Kufra airbase to investigate reports of armed Sudanese crossing the border in vehicles. Its pilot and co-pilot were discovered dead the next day (Libya Observer, May 24, 2017).

It was not the first. In 1940, a Bristol Blenheim light bomber being used for reconnaissance by Free French forces was forced down near Jabal ‘Uwaynat. Its crew wandered in the desert for 12 days before being picked up by an Italian patrol and packed off to Italy as prisoners. A second Free French Blenheim went missing on February 5, 1942 after a bombing mission on the Italian-held al-Taj fort at Kufra. The plane and the remains of its crew were discovered by a French patrol in the Ennedi region of Chad in 1959. [9]

A French Patrol Discovers the Lost Blenheim in Ennedi, 1959

A French Patrol Discovers the Lost Blenheim in Ennedi, 1959

Less fortunate were the crews of three South African Air Force Blenheims that became lost in May 1942 and were forced to land in the desert between Kufra and ‘Uwaynat when their fuel ran out. Only one man survived to be rescued; the others perishing in agony from heat, thirst and misguided attempts to preserve themselves through drinking the alcohol in their compasses and spraying themselves with blister-inducing foam from their fire-extinguishers. [10]

There are some surprising peculiarities to aerial surveillance in the open desert. Stationary vehicles can be extremely difficult to spot from the air, as patrols from the LRDG discovered while operating in the Libyan Desert in World War II. It became common practice to simply stop when the approach of enemy aircraft was heard, a tactic that saved many patrols no matter how counter-intuitive it might have seemed.

Modern Gateway for Rebels, Traffickers and Mercenaries

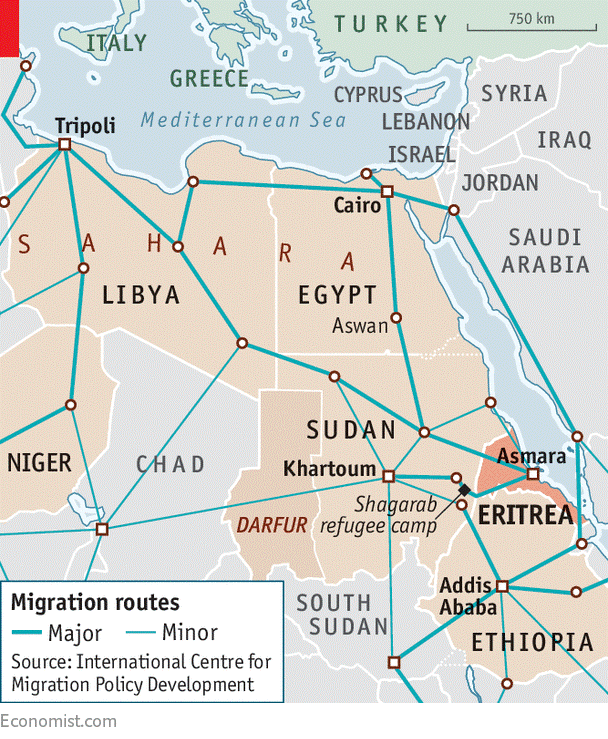

In the Qadddafi-era, a trans-Saharan desert road connecting Kufra through ‘Uwaynat to Sudanese Darfur was promoted as a means of establishing trade between the two regions. The collapse of security in southern Libya after the 2011 anti-Qaddafi revolution brought the route to the attention of smugglers, human traffickers and members of Darfur’s multiple rebel movements who were being slowly squeezed out of Darfur under pressure from Sudan’s security forces.

A June 1, 2017 report of the UN Libyan Experts Panel described how Darfuri rebel movements received offers for their military services from both rival governments in the Libyan conflict, broadly the Bayda/Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR) and its military arm, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), versus the Tripoli-based Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (GNA) and their allied Islamist militias. Due to a presence in Libya dating back to the Qaddafi-era (when the Libyan leader acted as a sponsor in their war against Khartoum), commanders such as Abdallah Banda, Abdallah Jana and Yahya Omda from Darfur’s largest rebel movement, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), were able to access Libyan networks to their benefit.

Rebel fighters from the rival Sudan Liberation Army – Minni Minnawi (SLA-MM) began operations in Fezzan in 2015 before joining LNA operations in the northern “oil crescent” in 2016. Fighters from another major rebel faction, the Sudan Liberation Army – Abdul Wahid (SLM-AW), were cited as being aligned with the LNA (Libya Herald, June 11, 2017). Through 2014-2015, there were numerous accusations from Haftar and his supporters that Khartoum was using the desert passage past ‘Uwaynat to send arms and fighters to reinforce Islamist militias in Benghazi, Kufra and elsewhere, resulting in a short diplomatic crisis. [11] Haftar recently claimed Qatar was funding the entry of Chadian and Sudanese “mercenaries” into Libya through the southern border (al-Arabiya, May 29, 2017).

Some 30 members of JEM, allegedly supported by Tubu fighters, were reported killed in two days of fighting north of Kufra in February 2016 (Reuters, February 5, 2016; Libya Observer, February 4, 2016; Libya Prospect, February 7, 2016). Some of the fighting took place at Buzaymah Oasis, 130 km northwest of Kufra, where the Darfuri rebels had attempted to set up a base. The Darfuris were attacked by Kufra’s Subul al-Salam Brigade, a Salafist militia formed in October 2015 and composed largely of Zuwaya Arabs, the dominant group in the Kufra region. Led by Abd al-Rahman Hashim al-Kilani, the militia was allied with Khalifa Haftar, who is reported to have supplied the unit with 40 armored Toyota 4x4s in September 2016 (Libya Herald, October 20, 2016). After a number of kidnappings and highway robberies committed by the alleged JEM fighters, the Subul al-Salam group again engaged the Darfuris in October 2016, killing 13 fighters. An October 23, 2016 Sudanese government statement claimed the Darfuris were supporters of Khalifa Haftar. [12] Subul al-Salam also clashed with Chadian gunmen 400 km south of Kufra on February 2, 2017, killing four of the Chadians, possibly Tubu from the Ennedi mountain range south of the border (Libya Observer, February 2, 2017).

A May 2017 Sudanese intelligence report repeated nearly year-old claims that elements of the Darfuri Sudan Liberation Movement – Minni Minawi (SLM-MM) under local commander Jabir Ishag were active in the Libyan south around Rabaniyah and around the oil fields north of Kufra. The report also claimed the presence of SLM-Unity and SLM-Abd al-Wahid (SLM-AW) units northeast of Kufra and JEM forces under commander al-Tahir Arja in the north, near Tobruk, where they were alleged to be supporting Khalifa Haftar (Sudan Media Center, May 22, 2017; Libya Observer, October 10, 2016; GMS-Sudan, July 27, 2016).

Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces Deploy at ‘Uwaynat

Sudanese troops were reported to have moved up to the Jabal ‘Uwaynat region on June 2, 2017 (Libyan Express, June 3, 2017). Most of these were likely to belong to Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF – Quwat al-Da’m al-Seri), a 30,000 strong paramilitary that was integrated into the Sudanese Army in January 2017. Prior to that, the paramilitary had operated under the command of the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS –Jiha’az al-Amn al-Watani wa’l-Mukhabarat ) and became notorious for the indiscipline and human rights abuses common to the infamous Janjaweed, from which much of the strength of the RSF was drawn at the time of its creation in 2013. The disorderly RSF has even been known to clash with units of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF).

Besides recruitment from a variety of Arab and non-Arab tribes in Darfur, the RSF also employs many Arabs from Chad, former rebels against the Zaghawa-dominated regime of President Idriss Déby Itno. Designed for high mobility, the RSF claims it can reach the Libyan border within 24 hours of an order for deployment (Sudan Tribune, January 17, 2017). [13] The RSF leader is Lieutenant General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo (a.k.a. Hemeti), a member of the Mahariya branch of the Darfur Rizayqat. The RSF enjoys the patronage of Sudanese vice-president Hassabo Abd al-Rahman, who is, like Daglo, a member of the Mahariya branch of the Rizayqat. Hemeti is nonetheless despised by many SAF officers as an illiterate with nothing more than a Quran school education (Radio Dabanga, June 4, 2014).

A June-July 2016 deployment of the RSF in the ‘Uwaynat region led to the arrest of roughly 600 Eritrean and Ethiopian illegal migrants, most of whom were attempting to reach Europe or the United States. The RSF activity was in step with a European Union grant of €100 million to deal with illegal migration that followed a Sudanese pledge to help stop human trafficking to Europe (Sudan Tribune, July 31, 2016). The funds were intended to construct two detention camps for migrants and to provide Sudanese security services with electronic means of registering illegal migrants. The traffickers, however, do not always go quietly; in April 2017 the RSF engaged in “fierce clashes” with human traffickers, leading to the arrest of five of their leaders and the capture of six 4×4 vehicles. According to one smuggler of migrants, the presence of the RSF has changed the situation on the border: “The road to Libya is still working, but it’s very dangerous” (The Economist, May 25, 2017).

A June-July 2016 deployment of the RSF in the ‘Uwaynat region led to the arrest of roughly 600 Eritrean and Ethiopian illegal migrants, most of whom were attempting to reach Europe or the United States. The RSF activity was in step with a European Union grant of €100 million to deal with illegal migration that followed a Sudanese pledge to help stop human trafficking to Europe (Sudan Tribune, July 31, 2016). The funds were intended to construct two detention camps for migrants and to provide Sudanese security services with electronic means of registering illegal migrants. The traffickers, however, do not always go quietly; in April 2017 the RSF engaged in “fierce clashes” with human traffickers, leading to the arrest of five of their leaders and the capture of six 4×4 vehicles. According to one smuggler of migrants, the presence of the RSF has changed the situation on the border: “The road to Libya is still working, but it’s very dangerous” (The Economist, May 25, 2017).

The RSF commander has suggested Europe does not appreciate the RSF’s efforts in fighting illegal migration on their behalf, stating that despite a loss of 25 killed, 315 injured and 150 vehicles in the fight against illegal migration, “nobody even thanked us” (Sudan Tribune, August 31, 2016). Daglo went on to warn his troops could easily abandon their positions and allow the migrants and traffickers free passage. Whether Daglo was speaking for the government or on his own behalf is uncertain.

RSF commander Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemeti”

RSF commander Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemeti”

Only days after Daglo’s complaints, Yasir Arman, secretary-general of the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement–North (SPLA/M-N), claimed to have received details of a European operation to directly supply the controversial RSF with funds and logistical support. Arman maintained that this “Satanic plan” was intended to cover up the RSF’s participation in atrocities and genocide. The EU issued a prompt denial (Sudan Tribune, September 7, 2016). [14]

Rising Tensions between Egypt and Sudan

Egypt’s army has been engaged in a constant effort to prevent Libyan arms crossing its 1000 km border with Libya, the preferred route being to cross the border through the Libyan Desert and then on to the Bahariya Oasis in Western Egypt, connected by road with the Nile Valley. In late May 2017, Egypt’s president Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi announced that Egypt’s military had destroyed some 300 vehicles carrying arms across the Libyan border in the last two months alone (Ahram Online, May 25, 2017).

Last October, LNA chief-of-staff and HoR-appointed military governor of the eastern region, Abd al-Raziq al-Nathory, announced that Egyptian forces guarding the border with Libya had in some cases established positions as far as 40 km inside Libya (Libyan Express, October 15, 2016).

The issue of Darfur rebel groups entering Sudan from Libya, the possible establishment of a buffer zone on the border triangle between Egypt, Libya and Sudan, and a Sudanese proposal to create a joint border patrol force were addressed in a meeting between the Sudanese and Egyptian foreign ministers in Cairo on June 3, 2017 (Sudan Tribune, June 3, 2017). Tensions between Egypt and Sudan have flared up in recent weeks with new friction over the disputed status of the Halayib Triangle west of the Red Sea coast, Khartoum’s support for Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam construction (which Egypt claims will violate long-standing Nile Basin water-sharing agreements) and accusations from Khartoum of Egyptian material support for Darfuri rebels re-entering Sudan. Less than two weeks before the meeting, Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir announced that the RSF had seized Egyptian armored vehicles used by Darfuri rebels crossing the border near ‘Uwaynat from Libya, while Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and NISS Facebook pages posted photos of captured or destroyed Egyptian vehicles allegedly used by the rebels (Sudan Tribune, May 24, 2017).

Conclusion: From Isolation to Insecurity

Jabal ‘Uwaynat’s magnificent isolation is quickly becoming a romantic memory. Today it has become a focal point for modern scourges such as human-trafficking, narcotics smuggling and militancy-for-hire. Its apparent future is one of more frequent clashes, greater surveillance and the introduction of more imposing barriers to movement. To some degree, this undesirable future can be averted if Libya’s political house can be put in order in the near future, thereby reducing the demand for foreign guns-for-hire, enabling the imposition of proper border controls to deter human-trafficking and allowing the introduction of more effective cooperative security efforts between Libyan, Sudanese and Egyptian security services.

Notes

- For the Rock Inscriptions at Jebel ‘Uwaynat, see: Francis L. Van Note, Rock Art of the Jebel Uweinat (Libyan Sahara), Akadem. Druck- u. Verlagsanst, Graz, Austria, 1978; András Zboray, Rock Art of the Libyan Desert, Fliegel Jezerniczky Expeditions, Newbury, 2005 (DVD); Maria Emilia Peroschi and Flavio Cambieri, “Jebel Uweinat (Sahra Orientale) et l’Arte Rupestre: Nuuove Prospettive di Studio Dalle Recente Scoperte,” XXIV Valcomonica Symposium, Art and Communication in Pre‐literate societies, Capo di Ponte, Italy, 2011, pp. 339-345, http://www.academia.edu/30404525/The_rock_art_of_Jebel_Uweinat_Eastern_Sahara._New_perspectives_from_the_latest_discoveries.pdf

- For the Jabal ‘Uwaynat inscription of Mentuhotep II and its implications, see: Joseph Clayton, Aloisia De Trafford and Mark Borda, “A Hieroglyphic Inscription found at Jebel Uweinat mentioning Yam and Tekhebet,” Sahara 19, July 2008, pp.129-134; Andrés Diego Espinel, “The Tribute from Tekhebeten (a brief note on the graffiti of Mentuhetep II at Jebel Uweinat),” Göttinger Miszellen 237, 2013, pp.15-19, http://www.academia.edu/8699848/2013_-_The_tribute_of_Tekhebeten ; Julien Cooper, “Reconsidering the Location of Yam,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 48, 2012, pp.1-21,http://www.academia.edu/5646190/Reconsidering_the_Location_of_Yam_Journal_of_the_American_Research_Center_in_Egypt_48_2012_1-22 ; Thomas Schneider, “The West Beyond the West: The Mysterious “Wernes” of the Egyptian Underworld and the Chad Palaeolake,” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 2(4), 2010, pp. 1-14, https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/jaei/article/view/82/86 ; Thomas Schneider, “Egypt and the Chad: Some Additional Remarks,” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 3(4), 2011, pp.12-15, https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/jaei/article/view/12651/11932

- For example, the roughly 7,000 year-old Nabta Playa stone circle (northwest of Abu Simbel in Egypt’s Western Desert) has been subject to pointless damage, theft and even re-arrangement by unauthorized “New Age” tourists to better correspond to their own theories regarding its purpose. Rubbish dumps around the site attest to the thoughtlessness of these visitors and their unlicensed guides.

- Ralph A. Bagnold: Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1941 edition (orig. 1935), pp.188-189.

- A.M. Hassanein Bey: The Lost Oases, Century Co., New York, 1925, pp. 219-234.

- Bagnold, op cit, p.173.

- Michael Crichton-Stuart, G Patrol, Wm Kinder and Co., London, 1958, pp.54-55.

- For the SDF convoys on this route in WWII, see “The Kufra Convoys,” http://www.fjexpeditions.com/frameset/convoys.htm

- See http://aviateurs.e-monsite.com/pages/de-1939-a-1945/morts-de-soif-dans-le-desert.html

- See http://www.fjexpeditions.com/frameset/convoys.htm

- “Are Sudanese Arms Reaching Libyan Islamists through Kufra Oasis?” Tips and Trends: The AIS African Security Report, April 30, 2015, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=1482

- http://www.sudanembassy.org/index.php/news-events/1258-report-new-information-on-the-involvement-of-darfuri-rebels-in-the-conflict-in-libya

- For the RSF, see Andrew McGregor, “Khartoum Struggles to Control its Controversial ‘Rapid Support Forces’,” Terrorism Monitor, May 30, 2014, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?tag=rapid-support-forces; Jérôme Tubiana, “Remote-Control Breakdown: Sudanese Paramilitary Forces and Pro-Government Militias,” Small Arms Survey, May 4, 2017, http://www.css.ethz.ch/en/services/digital-library/articles/article.html/571cdc5a-4b5b-417e-bd22-edb0e3050428

- For Yasir Arman, see Andrew McGregor, “The Pursuit of a ‘New Sudan’ in Blue Nile State: A Profile of the SPLA-N’s Yasir Arman,” Militant Leadership Monitor, June 30, 2016, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3652