Andrew McGregor

December 20, 2007

In the midst of all the horrors generated in Central Africa by the Rwandan genocide of 1994 and the collapse of Zaire in 1997, a little known group of Islamist radicals has done its own part to contribute to the suffering. Based since 1996 in Bundibugyo, an impoverished and underdeveloped district in western Uganda, the Alliance of Democratic Forces (ADF) has killed thousands in its pursuit of an Islamic state in Uganda. Strangely enough, few of its rank and file are Muslims (or even Ugandans), and its leader is a convert from Catholicism. The movement was believed destroyed by the Ugandan Popular Defense Forces 1999 campaign, but seems to have enjoyed a revival after the discovery of oil in Bundibugyo. Now, however, there is word that the ADF is seeking peace talks with Uganda after a series of setbacks to enable the return of some 200 ADF fighters from the forests of the Congo to Uganda (Monitor [Kampala], December 4).

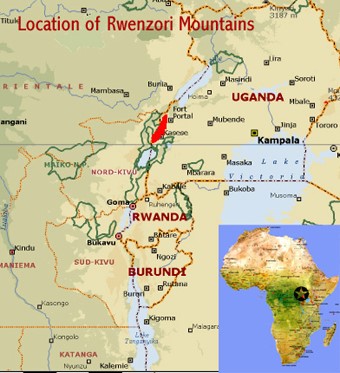

Bundibugyo is a small district at the foot of the Rwenzori Mountain range along the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It has a natural connection to the vast Ituri Forest, which has become a home for various regional insurgent groups. This mountainous area is the last region of Uganda to go without electricity and is notorious for the poor quality of its roads. Bundibugyo is currently enduring a bout of Ebola Fever that has killed 35 people (New Vision [Kampala], December 11). The ADF did not begin here, however, but started rather in the urban Muslim areas of Kampala and the towns of central Uganda.

The ADF has its origins in the evangelistic Tabliqi Jamaat movement of Uganda, a local offshoot of the larger Indian-Pakistani Tabliq movement founded in the 1920s. Tabliq means “to deliver (the message of Islam).” Muslims are a minority in mostly Christian Uganda, representing about 15 percent of the population. While the Indian-Pakistani Tabliq movement is usually non-political, the Ugandan Tabliqis claimed political persecution after they opposed the appointment of a new national mufti. Following a period of street-clashes and arrests in 1991, many in the Tabliq movement left for the wilds of the Rwenzori mountains where they were joined by radicalized prisoners released in 1993. The absence of Muslims in the higher ranks of President Yoweri Museveni’s administration also contributed to the growing militancy of the Tabliq movement. According to the Ugandan government, the Tabliqis received funds and encouragement from the Sudanese embassy in Kampala, leading to the severing of diplomatic ties in 1995. [1]

The first major strike by the ADF took place in 1996, when the movement’s fighters attacked Ugandan troops in Kasese District along the border with the Congo. At first most of the fighters had little more than machetes, but arms began to flow to the movement from external sources, most likely the Sudan or the DRC government of Laurent-Desire Kabila. During the 1990s, ADF militants carried out 43 bombings in Kampala and Jinja. Never well liked within Uganda, the ADF leaders found it simpler to recruit new fighters from the DRC by offering promises of money and education. Many children were seized on both sides of the border and incorporated into the ranks.

Once in western Uganda, the ADF formed an alliance with the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (NALU), a rebel group that had become fairly inactive. NALU was formed in 1988 and split from the Rwenzori Movement in 1991 [2]. NALU tactics typically involved raids on small villages and attacks on civilians, including a 1998 suicide bombing on a Kampala bus that killed 30. Eventually the ADF was also joined by remnants of the Rwenzori separatist movement and a number of Idi Amin loyalists who were living in the south Sudan.

Kampala’s campaign against the ADF was slow to develop but finally bore fruit in 1999. Borders were secured, roads brought under control, UPDF outposts placed on the high ground of the mountains, and self-defense units organized in the villages (IRIN, December 8, 1999). Despite this, the already impoverished Bundibugyo District was still forced to cope with over 100,000 displaced people.

ADF leader Jamil Mukulu was an associate of Osama bin Laden during the latter’s stay in Sudan in the 1990s, before launching his first attack in Uganda in 1996. Mukulu is believed to have received training from al-Qaeda both in Sudan and Afghanistan (Monitor, December 1). The ADF leader remains a shadowy figure, usually heard only on the cassette tapes the ADF distributes. Mukulu urges violence against non-Muslims and Muslims who fail to carry out jihad, including a heavy dose of invective against various international leaders: “Let curses be to Bush, Blair, the president of France—and more curses go to Museveni and all those fighting Islam.” According to Lieutenant-Colonel James Mugira, Uganda’s acting chief of military intelligence, “We think [Mukulu] will become the next bin Laden of Africa” (IWPR, June 6, 2005).

The ADF Attempts to Join the Global Jihad

On December 5, 2001, the ADF was added to the U.S. list of designated terrorist organizations. In the chaos that followed the entry of U.S. troops into Baghdad in 2003, reporters were able to obtain a cache of papers from the bombed-out ruins of Iraq’s intelligence headquarters. Among the documents were a series of letters from the ADF’s “chief of diplomacy,” Bekkah Abdul Nasser, to Fallah Hassan al-Rubdie, the Iraqi chargé d’affaires in Nairobi. These 10-15 page English-language letters (translated into Arabic by the Mukhabarat) seek Iraqi financing to set up an African mujahideen front: “We in the ADF forces are ready to run the African mujahideen headquarters. We have already started and we are on the ground, operational.” Another letter suggested the creation of an “international mujahideen team whose special mission will be to smuggle arms on a global scale to holy warriors fighting against U.S., British, and Israeli influences in Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East” (Christian Science Monitor, April 18, 2003; Daily Telegraph, April 17, 2003). There was no indication from the files that Iraqi funds were ever sent, or that the correspondence was even encouraged.

During a visit to Washington in 2004, Ugandan Defense Minister Amama Mbabazi emphasized that “Uganda’s domestic terrorist groups have been subsidized and trained by al-Qaeda” (Afrol News, September 30, 2004). Uganda has been a beneficiary of the $100 million U.S.-financed East Africa Counterterrorism Initiative (U.S. Department of State, April 1, 2004).

By 2005, Ugandan officials were warning the ADF had regrouped and were receiving funding and training from other extremist groups. According to Captain Joseph Kamusiime, operations chief for the Ugandan anti-terrorism unit, the ADF had supporters in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, but its chief backer was Sudanese Islamist Hassan al-Turabi, leader of the National Islamic Front. In the early days after its creation in 1996, the ADF was reported to have received training at a camp run by Sudanese intelligence in Juba (Islamism and its Enemies in the Horn of Africa, 2004). By 2005 Ugandan intelligence estimated 650-1,000 ADF fighters to be in the Congolese bush, but other sources claimed many of these were only camp-followers. Kamusiime described the ADF as part of a larger Islamist project: “The ADF… is motivated by Islamic fundamentalists—more in line with al-Qaeda ideology like other African terrorist organizations with global reach, such as the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, and Somalia’s Al-Ittihad al-Islamiya” (IWPR, June 6, 2005).

A Struggle Going Nowhere?

The 2005 signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Khartoum government and the rebel Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) in southern Sudan ended the usefulness of the ADF and Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) to Khartoum as counter-measures against Ugandan support for the SPLM/A. The last major attack by the ADF occurred in March, when 60 rebels crossed from the Congo into Bundibugyo to strike the new oil facilities. At least 45 guerrillas, including senior commander Bosco Isiko, were killed in a battle with the UPDF along the Sempaya River in the Semliki game reserve on March 27 (Radio Uganda, April 3; Monitor, November 20). In the three months between April and June of this year, nine ADF commanders were killed by the UPDF, effectively destroying the group’s command structure (New Vision, June 19).

ADF Leader Jamil Mukulu during Extradition Hearing in Tanzania, 2015

ADF Leader Jamil Mukulu during Extradition Hearing in Tanzania, 2015

Seven captured ADF rebels were granted amnesty in November after undergoing “psycho-social counseling” by the Ugandan Red Cross and officers of the UPDF (Monitor, November 21). Four Ugandans who aided the organization from the Ugandan side of the border with the Congo were not so lucky—they have been charged with treason (New Vision, October 12).

Ugandan security services claim to have interrupted a plot to bomb last month’s Commonwealth summit in Kampala. The plan, allegedly devised by ADF leader Jamil Mukulu, involved the use of state television vans to deliver bombs through security lines (The Monitor, December 1). Intended targets included the queen and about 45 other international leaders in attendance. Extensive searches of the vans by the Presidential Guards Brigade turned up nothing, but the security services claimed a success.

Conclusion

MONUC (Mission de l’ONU en RD Congo) has confirmed that the ADF has approached the UN mission to facilitate peace talks with Kampala. The initiative seems to have been spurred by a rift between Jamil Mukulu and his deputy Abdallah Kabanda (Monitor, December 4). MONUC is already demobilizing and resettling ADF rebels in the eastern Congo before a final operation to flush out remaining rebels in the region (New Vision, December 2). In a new complication for the Ugandans, Congolese dissidents are now crossing into Uganda to take refuge there from DRC/MONUC sweeps.

There is no question that some of the Ugandan estimates of ADF strength were exaggerated and the description of Jamil Mukulu by Ugandan intelligence as “the next bin Laden” seems calculated to draw U.S. military and financial assistance. Nevertheless, the ADF has been an integral part of a wave of violence that has denied security and development to millions of Africans in the Congolese-Ugandan-Rwandan border region. The collapse of this would-be international jihadi movement would be a welcome development in returning peace and security to this beleaguered part of Africa.

Notes

- Alex de Waal, ed.: Islamism and its Enemies in the Horn of Africa, Indiana University Press, 2004.

- The Bakonjo-Baamba people of Rwenzori made an abortive attempt at independence for the Rwenzori region in 1962. While the attempt failed, a small separatist movement lived on in the bush.

This article first appeared in the December 20, 2007 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.