Andrew McGregor

March, 2001

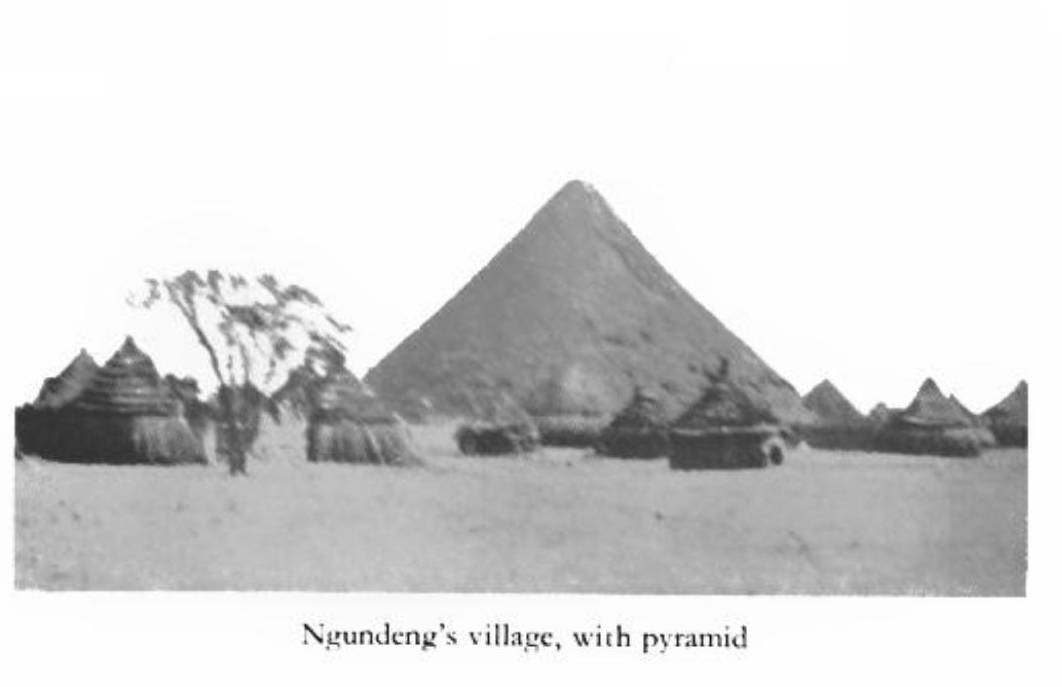

Over the last century, a great deal has been discovered about the pyramids of the Egyptian Old Kingdom. We know something of the technique used to build them, we are fairly confident of their purpose and we have certain bureaucratic records shedding light on some aspects of the organization of the work-force involved. What often seems to elude us is the motivation of the workers who endured back-breaking labour and, no doubt, many untimely deaths. What also seems strange is the rapidity with which the Egyptians moved from building rather modest monuments to the immense works of the Third and Fourth Dynasties. These developments seem to be inextricably tied to the processes of social unification and state formation. In the Nuer pyramid of Ngundeng we have an interesting parallel from recent times of a decentralized society with no prior experience of cooperative labour or monument building suddenly uniting to build an impressive and well-made structure. This little known work from the southern reaches of the Nile can shed some light on the processes involved in the transformation of Egyptian society some 4,500 years earlier.

The Nuer are one of the largest groups of Nilotic peoples in the South Sudan. As with other Nilotes, their origins and history are as yet poorly understood. A traditional political system is difficult to identify within Nuer society, which anthropologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard once described as “organized anarchy.” The leopard-skin chief is a figure of priestly rather than political authority, and Nuer tended to organize under central leadership only when faced with an unusual outside threat. Even then, the unification of different Nuer groups under a single individual was extremely rare. Evans-Pritchard, whose work on the Nuer was long a staple of college anthropology courses, tended to overemphasize the egalitarianism of Nuer society, ignoring the emergence of a so-called “aristocratic” class of Nuers.

The Nuer are one of the largest groups of Nilotic peoples in the South Sudan. As with other Nilotes, their origins and history are as yet poorly understood. A traditional political system is difficult to identify within Nuer society, which anthropologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard once described as “organized anarchy.” The leopard-skin chief is a figure of priestly rather than political authority, and Nuer tended to organize under central leadership only when faced with an unusual outside threat. Even then, the unification of different Nuer groups under a single individual was extremely rare. Evans-Pritchard, whose work on the Nuer was long a staple of college anthropology courses, tended to overemphasize the egalitarianism of Nuer society, ignoring the emergence of a so-called “aristocratic” class of Nuers.

The Nuer prophet Ngundeng was born sometime between 1850 and 1860, and was a member of a leopard-skin clan of the Lou Nuer. Members of such a clan were often referred to as kuaar muon, or earth-priests, as they were felt to have a mystical relationship with the soil. Since the prosperity of all Nuer was closely tied to the earth, such figures occupied an unusual position as potential mediators between various factions of the Nuer, who were habitually involved with blood-feuds and other mutual antagonisms. Ngundeng is usually thought to have been of Dinka descent, the Dinka being the largest of the Nilotic tribes of the South Sudan. Ngundeng spoke Dinka fluently, and was familiar with Dinka manners and customs. As other young Nuer men learned to hunt and fish, Ngundeng spent his days fasting, mumbling incantations and speaking in tongues, earning as well a reputation for being able to self-levitate and to transform himself into a goat. It is said that, as a youth, he deprived anyone who displeased him of the power of speech (save his mother, who was immune), and as a result many of his village neighbors moved to more remote parts. In his early days as a prophet, Ngundeng was said to live for weeks in the bush by himself, surviving on animal and human excrement. He later developed a taste for re-cooked ashes. Evans-Pritchard considered him a genuine psychotic, but nevertheless, Ngundeng’s growing reputation brought him an unusual amount of wealth and wives. It should be noted that the eating of unclean food was also characteristic of the Judaic prophets, and is related to an inversion of normal modes of behavior that helps set the prophet apart from the ordinary individual.

When his first son was born, Ngundeng announced that the particular spirit that the particular spirit that possessed him was called Dengkur, “Deng” being a Dinka word for God, and “kur” being a Nuer term for angry.

At a time just prior to the construction of the pyramid the Gaajok Nuer women were enduring a period of general infertility. In return for curing these women of their barrenness, usually by spitting on them (a traditional means of bestowing blessings in many parts of the Sudan), Ngundeng accepted payment in the form of ivory tusks, beads and cattle. At the same time, smallpox was striking the Nuer, and their cattle were afflicted with rinderpest. Ngundeng came up with the idea of burying the plagues beneath a huge mound that would contain them. Such an idea was revolutionary for the Nuer, who were entirely unaccustomed to extensive or sustained cooperative labour.

The work, which began about 1870, was carried out in three stages: first was the construction of huts for the workers, and while these were being built Ngundeng required payment for his services in grass, timber or labour. This phase lasted one winter season. The second phase lasted two years, and consisted of the accumulation of grain and corn, usually brought to the village by any visitor of passer-by who did not wish to incur the wrath of Ngundeng. When the granaries were full, Ngundeng went into seclusion, fasting for seven days, followed by passing into a trance for three days. At this time word went out for the Nuer to congregate at Ngundeng’s village. The Nuer, forgetting all their customary blood feuds, gathered from points all over the South Sudan until, so it is said, the plain was black with people. After exhorting the crowd for an entire night under a full moon, Ngundeng carried the first load of earth to the site of the mound. For four years, thousands of Nuer worked under his supervision constructing the Bie Dengkur, the mound of Dengkur.

The construction of large mounds built of ash, cattle dung, cotton soil and clay was not without precedent in the South Sudan, though it had not been known among the Nuer previous to Ngundeng’s time. These works are variously said to have been made as monuments to the prophets who ordered their construction, or as burial mounds for the prophets, who were buried, sometimes alive, either beside or beneath them. The model for their shape appears to be the only non-domestic structure traditionally built in the South Sudan, the cattle hut. Two very prominent Dinka mounds can be mentioned in this regard; being those of Ayong Dit and Pwom Ayeuil. The first is built north of Malakal, and remains, like the other, an important shrine. This mound, known as Yiek Ayong, is said to have been built over the body of Ayong Dit, who was bricked up by his own orders in his cattle hut with his wife and eight favorite bulls. A ceremony was held every eight years, during which the mound was repaired and eight bulls sacrificed.

The second mound, known as Pwom Ayeuil (the mound of Ayeuil), is situated on the island formed by the Bahr al-Zeraf and the Bahr al-Jabal. The mound is the work of the Luac Dinka, who are known to have been driven from this area in 1820, and must therefore predate this event, making it at least 180 years old. Beside this monument, which is now much weathered and reduced in height by years of heavy rain, is the grave of Ayeuil Longar, the reputed ancestor of no less than five sections of the Dinka. Traditional tales tell of the many deaths of workers on the mound and the incorporation of their corpses into the structure. Other tales tell of human bodies being used as props in the scaffolding, the individuals being buried alive in the construction of the mound. The Dinka word for these mounds, yik, is also used in describing the mound of Dengkur, suggesting a direct relationship between the Ngundeng project and the earlier Dinka mounds.

The mound of Dengkur was some 300 feet in circumference and 50 to 60 feet high, surrounded by a row of elephant tusks. In form it was a perfect cone; the term “pyramid” is the one applied to it by British colonial administrators. Other tusks were buried within the centre of the mound, along with the horns of a white bull, the entrails of a goat, and various bones. The use of elephant tusks was more than decorative; in Nuer cosmology, elephants possess a spiritual power linked to the destiny of men and were in some ways regarded as cousins to the Nuer. At the peak of the mound was a spear decorated with an ostrich egg and ostrich feathers.

In the years following the completion of the Bie Dengkur, Arab slavers twice attacked the area and carried off all the people and ivory they could, but the mound was kept in good repair and served as a rallying point for Nuer warriors. At some point during this difficult period, Ngundeng had an elaborate brass pipe made for him by an Anuak craftsman. The manufacture of this object was kept secret until one morning the astonished Nuer observed the pipe sitting by itself at the peak of the mound with smoke issuing from its bowl. The pipe quickly assumed its own magic, being said to render its possessor invulnerable, as well as serving as a death-dealing weapon, reputedly felling both men and cattle at a mere wave. Ngundeng let it be known that the pipe would play a major role in ridding Nuer country of the hated “Turks,” as Ottoman, Egyptian and British forces were all known. Ngundeng died in 1906, before the final struggle between the “Turks” and the Nuer.

Ngundeng had become the father of twin sons, Gwek and Lil, in 1883, but it was initially felt that the spirit of Dengkur had passed to his eldest son, Reth. It was Gwek, however, who appeared to have been possessed by Dengkur, speaking in tongues, standing on his head atop the mound, and allegedly transforming himself into a goat. Goats were normally associated with women and cattle with men; the transformation into a goat is again a type of behavioral inversion associated with sexual ambiguity. The matter of Gwek’s status was sealed when Gwek was spotted smoking the brass pipe on top of the mound, for the pipe had not been seen since Ngundeng’s death, presumably having accompanied him to the spirit world. The name “Gwek” means “frog,” and was said to have been given to him as a result of Ngundeng feeding Gwek’s mother frogs as a method of increasing her fertility. Those who knew the adult Gwek felt the name was especially suited to this short, squat, large-headed individual who was known for drooling at the mouth. Quite likely Gwek was an epileptic, experiencing seizures almost daily, during which he would shake, foam at the mouth and scream at the top of his lungs, quite often while standing atop the mound. The Nuer did not haphazardly appoint madmen or epileptics (gwan noka) to positions of authority. Symptoms of epilepsy could only be regarded as signs of prophethood when they were accompanied by a perceived success in curing barrenness, healing, rain-making, divining the future, stopping epidemics and leading raids. The sociologist Max Weber classed such people as “charismatic berserks.”

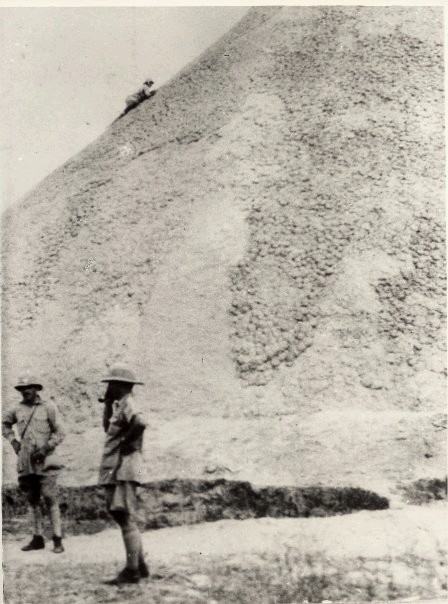

No one ever saw Gwek climbing or descending the mound; one British officer making a visit to the village thought that Gwek would go up in the night and descend the next night, but he was unable to observe him doing either, despite his best efforts. Climbing the mound was no easy feat, as another British officer later found out. The sides were exceptionally smooth with no handholds. After reaching the top with the assistance of a native trooper, the officer described his descent as “an involuntary and painful slide.”

Although the Anglo-Egyptian army had taken control of the Sudan in 1898, it was not until 1916 that patrols were sent into Nuer country in the Upper Nile province. The Nuer prophets were noted by the administration as having been responsible for leading raids against neighboring tribes, a practice that continued into the 1940s. By 1918, Gwek was leading large raids against the Dinka and even massacred a company of the 9th Sudanese Regiment. Gwek normally went into battle carrying his pipe and a magical fishing spear (normally a ritual object associated with the Dinka) and leading a white bull – an animal that was especially associated with rain-making ceremonies and accompanied Nuer prophets on raids against the Dinka. A government patrol in 1918 met Gwek’s advance on them with a burst of machine-gun fire. The bull was killed with its head pointing towards the Nuer, a signal for immediate retreat.

HC Jackson, then Deputy Governor of Upper Nile province, visited the mound in 1921 with a small escort of native police. Gwek refused to see him, and the small group was soon surrounded by a large number of angry warriors. With little chance of being able to fight their way out, Jackson defused the situation by breaking out his canvas field bath and having an impromptu bath, much to the amusement of the warriors.

Relations between Gwek and the government deteriorated, however, as courts and a native police force were established, greatly reducing both Gwek’s authority and his income. The situation grew worse as the government proposed building a road through Nuer country, connecting it with the territory of their traditional rivals, the Dinka. Over 20 years earlier, Ngundeng had made a prophecy that the Turks would defeat the Nuer in battle many times before making “a great white path” to the Nuer border. At that point a plant would sprout atop the mound of Dengkur. When it reached the height of a man, the Nuer would rise up and drive the Turks out forever. Soon hundreds of bulls were being sacrificed at the base of the mound and warriors began to arrive from all over Nuer land, including forces under the leadership of two other prophets, Char Koryom and Pok Karajok. In 1927, District Commissioner Captain V.H. Fergusson was allegedly murdered along with a Greek merchant and a number or Dinka bearers by a group of Nuer, an action that resulted in an order to arrest Gwek. The perceived threat from the Nuer prophets was even raised in the British House of Commons, and Gwek and Pok Karajok were immortalized in a few lines from the satirical Punch magazine:

I fear that Messsrs. Pok and Gwek

Will shortly get it in the neck

And that an overwhelming shock

Is due to Messrs. Gwek and Pok

Then let us mourn the bitter wreck

In store for Messrs. Pok and Gwek

When we administer the knock

To Mr. Gwek and Mr. Pok.

The eventual advance of a large force of government troops succeeded in dispersing the Nuer. When the patrol reached the mound, which by this time was recognized by the government as a symbol of Nuer resistance, a group of engineers spent a week digging a tunnel into the base of the mound, in which they place a charge of high explosives. The Nuer warriors were assembled for a display of government power and told to watch the mound closely, for it would vanish on a signal from the British leader of the patrol. The attempt to destroy the mound was a failure, however. As Percy Coriat, the Nuer-speaking officer involved described it, “a puff of white smoke and a few lumps of earth tumbling down the side was all they saw.” The mound was attacked by the Royal Air Force in 1927, but bombs failed to destroy it. Gwek remained at large and raids and other disturbances continued. In January 1929, another government column was dispatched to the pyramid.

Percy Coriat climbing the “pyramid,” 1928

Percy Coriat climbing the “pyramid,” 1928

Arriving at 5:30 in the morning, they found large numbers of spear-carrying warriors dancing at the base of the mound. Magic water was given to the warriors, who were told that it would render them immune to bullets and taxes, while reeds were given out in the understanding that they would be magically transformed into guns once the battle began.

The column formed a square and began firing over the heads of the warriors in an effort to provoke a charge. The shots had their desired effect and soon the Nuer were rapidly advancing, singing and driving Gwek’s white bull before them. When they had reached 120 yards from the square the government troops opened a withering fire that broke the charge. Gwek’s body and pipe were found beside the slain white bull. The prophet had got closer to the square than anyone else. Though the action wasn’t quite the “Battle of the Pyramids” fought between Napoleon and the Mamluks, it nevertheless had as great an impact on the Nuer of the South Sudan, ending for the most part all resistance to the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium government.

After the battle, the British hung Gwek’s body in a tree so that all the Nuer could see that he was truly dead. Gwek’s pipe wound up in the hands of District Commissioner Alban, who liked to shock the local Nuer by having a smoke from it. Eventually it was destroyed in a fire, but the pieces were recovered and presented to the Khartoum Museum.

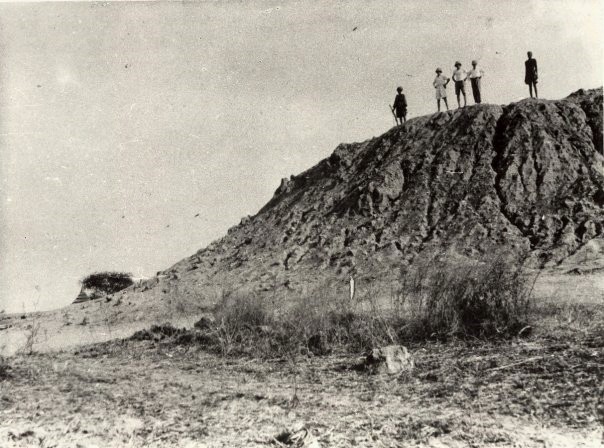

The ruined mound stood for many years, with the Nuer prevented by the government from effecting any repairs. As late as 1940, a plague of locusts prompted Gwek’s twin brother, Lil, to request that the mound be “closed up” in order to enclose and bury the plague. Permission was refused.  The Bie Dengkur after its Partial Demolition by Government Forces.

The Bie Dengkur after its Partial Demolition by Government Forces.

In conclusion, we can see some similarities and differences between the Bie Dengkur and the Old Kingdom pyramids:

1/ The Egyptian pyramids were built at the instigation of a divine (or semi-divine) king, while the Nuer mound was built under the direction of a prophet who acted as a spokesman for God.

2/ In time, the pyramids of the Old Kingdom came to symbolize the over-concentration of power and wealth in one individual’s hands leading to resentment and the looting of these structures as early as the First Intermediate Period. The mound of Dengkur, however, came to serve as both a symbol of Nuer resistance to outside aggression and as a means of controlling some of the more inimical elements of nature.

3/ The Egyptian works served as funerary monuments for the benefit of one individual, while the mound of Dengkur was rather more functional, serving to bury plague and disease for the benefit of the entire community.

4/ Both works assisted, intentionally or not, in the unification of fractious but otherwise homogenous peoples and in the mass organization of labour. In this sense, the pyramids of Egypt were vitally important in the formation of a powerful state; the inspiration of Ngundeng might likewise have enabled the Nuer to assume a politically dominant position in the South Sudan had a more advanced culture not interfered at a vital point in their development of a proto-state.

Bibliography

Alban, A.H.: “Gwek’s pipe and pyramid,” Sudan Notes and Records 23(1), pp. 200-201.

Biedelman, T.O.: “Nuer priests and prophets: charisma, power and authority among the Nuer,” in: T.O. Biedelman (ed.), The Translation of Culture, London, pp. 375-415.

Burton, J.W.: “A note on Nuer prophets,” Sudan Notes and Records 54, pp.95-107.

Coriat, Percival: “Gwek the witch-doctor and the pyramid of Dengkur,” Sudan Notes and Records 22(2), 1939, pp.221-37.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E.: “Customs and beliefs relating to twins among the Nilotic Nuer,” Uganda Journal, 1936, pp.230-38.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E.: The Nuer, Oxford, 1940

Greuel, P.J.: “The Leopard-skin chief: An examination of political power among the Nuer,” American Anthropologist 73, 1971, pp.115-20.

Howell, P.P.: “Pyramids in the Upper Nile Region,” Man 48, 1948, pp.52-53.

Jackson, H.C.: Sudan Days and Ways, MacMillan and Co., London, 1954.

Johnson, Douglas H.: “Foretelling Peace and War: Modern Interpretations of Ngundeng’s Prophecies in the Southern Sudan,” in: M.W. Daly (ed.): Modernization in the Sudan: Essays in Honor of Richard Hill, Lilian Barber Press, New York, 1985

Johnson, Douglas H.: Nuer Prophets: A History of Prophecy from the Upper Nile in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Clarendon Press, 1997

Kelly, Raymond C.: The Nuer Conquest: The Structure and Development of an Expansionist System, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1985

Kingdon, F.D.: “The Western Nuer Patrol,” Sudan Notes and Records 32, 1945, pp. 77-84.

Stigand, G.H.: “Warrior classes of the Nuers,” Sudan Notes and Records 1, 1918, pp.116-18.

Thomas, L.: “The Nuer Patrol, 1927-28,” in D. Lavin (ed.), The Condominium Remembered: Proceedings of the Durham Sudan Historical Records Conference 1982, Vol. 1, Durham, 1991, pp. 108-110.

A transcript of this lecture was first published in Proceedings of the Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations Graduate Students’ Annual Symposia 1998-2000, Benben Publications for the University of Toronto, 2001, pp. 201-210.