Andrew McGregor

AIS Tips and Trends: The African Security Report

June 30, 2015

Libya’s Islamic State (IS) group exploited its seizure of the Mediterranean port city of Sirte in May by moving south from the city to Ghardabiya to claim Libya’s largest air-base and one of its largest reservoirs of fresh water. A one-time Qaddafist stronghold some 450 kilometers east of Tripoli, Sirte has seen many of its residents flee to evade the IS takeover, a repetition of the 2011 exodus when the city was under attack by revolutionary anti-Qaddafi forces.

Weeks of fighting around Sirte preceded the Islamic State’s mid-May breakthrough. The decisive action was the result of an IS counter-attack that overran the 166 Brigade’s camp in Sirte following the collapse of a Misratan offensive against IS forces (libya-analysis.com, May 25, 2015).

Weeks of fighting around Sirte preceded the Islamic State’s mid-May breakthrough. The decisive action was the result of an IS counter-attack that overran the 166 Brigade’s camp in Sirte following the collapse of a Misratan offensive against IS forces (libya-analysis.com, May 25, 2015).

166 Brigade, part of the Libya Dawn coalition of militias supporting the Islamist-dominated General National Congress (GNC) government in Tripoli, arrived in Sirte from Misrata in March in an effort to expel an estimated 500 IS fighters from the city but encountered stiff resistance almost immediately, beginning with a deadly ambush (al-Jazeera, March 18, 2015).When the 166 Brigade withdrew from Sirte on May 28, IS forces moved quickly to take the military prize, the Ghardabiya airbase, a joint military/civilian facility that Libya Dawn was using to mount airstrikes on the Libyan National Army (LNA). The base was badly damaged in a March 2011 airstrike by U.S. B-2 Spirit stealth bombers during the Libyan revolution.

It is uncertain whether any military or civilian aircraft were still present at the airbase when it was abandoned, though a 166 Brigade spokesman insisted that only a single “non-functioning and unrepairable warplane” remained when IS forces moved in. Misratan officials blamed the withdrawal on the GNC, claiming the rival government had failed to provide the necessary support to the Misratan militia (Libya Herald, May 29, 2015).

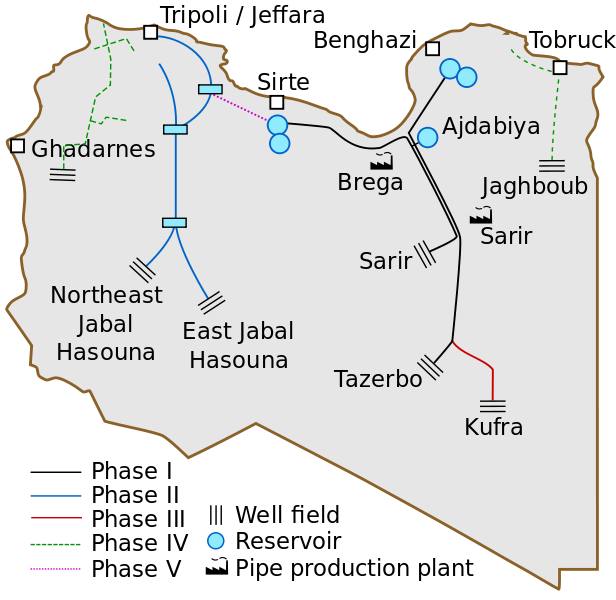

IS also succeeded in seizing al-Gardabiya Reservoir, a vast water storage facility of 15.4 million cubic metres roughly a kilometer wide. The second-largest in Libya, the reservoir forms a terminus point for Libya’s Great Man-Made River (GMMR), an underground network of pipes that pumps water from sandstone aquifers beneath the desert to coastal cities where most of the population is concentrated.

IS also succeeded in seizing al-Gardabiya Reservoir, a vast water storage facility of 15.4 million cubic metres roughly a kilometer wide. The second-largest in Libya, the reservoir forms a terminus point for Libya’s Great Man-Made River (GMMR), an underground network of pipes that pumps water from sandstone aquifers beneath the desert to coastal cities where most of the population is concentrated.

A Libya Dawn spokesman explained the differing approaches of Libya Dawn and General Khalifa Haftar’s Operation Dignity forces supporting the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR, the internationally recognized government of Libya): “We are against terrorists in all forms, but not to do it Haftar’s way, which is to destroy a city and make families flee, all to end a couple of hundred terrorists” (al-Jazeera, March 18, 2015). Libya Dawn’s approach has led to accusations from Operation Dignity supporters that Libya Dawn is not serious about countering the Islamic State threat. However, Libya Dawn’s approach to IS underwent significant changes after the May 31 IS suicide bombing at the Dafniyah checkpoint outside Misrata that killed five Libya Dawn security personnel (Libya Herald, May 31, 2015). The attack followed a May 21 IS suicide bombing at another Misratan Libya Dawn checkpoint that killed two guards.

Much of Sirte was destroyed in the 2011 fighting.

Much of Sirte was destroyed in the 2011 fighting.

These attacks appear to have shattered any perception within Libya Dawn and the GNC that a more tolerant approach to the Islamic State would allow the Libya Dawn coalition to concentrate their forces against the HoR and Operation Dignity. Libya Dawn aircraft have sought revenge for the IS suicide bombings by striking a former Qaddafi regime security headquarters in Sirte used by IS fighters on June 22, followed by another raid on IS positions in Sirte by aircraft from Misrata on June 24 (Reuters, June 22, 2015; Libyan Herald, June 24, 2015).

Projections

Rampant insecurity, inability to market Libya’s much-diminished oil production, an absence of central financial control, electricity shortages, labor unrest, the flight of foreign workers and the destruction or incapacitation of necessary infrastructure has led Libya to the brink of full economic collapse, with the accompanying collapse of Libya’s last remaining civil institutions not far behind.

The West continues to decline any role in expelling or otherwise defeating Islamic State forces that threaten Western interests daily, a curious contrast to the rapid mobilization of Western military forces in 2011 against the regime of Mu’ammar Qaddafi, which no longer posed any threat to the West. NATO air power was decisive in Qaddafi’s overthrow by a mish-mash of poorly-organized militias without any cohesive ideology other than hatred of Qaddafi. Europe must now deal with the prospect of the IS using its control of a major port and a significant portion of coastline to launch overloaded boats full of African migrants, achieving the dual purpose of financing the IS while destabilizing European security.

The seizure of Sirte has enabled the Islamic State to achieve several strategic objectives, including the seizure of a small port, a military airbase and a massive reservoir of fresh water. Besides dealing their Misratan and Libya Dawn opponents a devastating blow, control of Sirte has also allowed IS to cut the vital coast road at a point almost in the middle of the country. Though it is possible the airbase no longer had any aircraft at the time it was abandoned to IS, the ineffectiveness of General Haftar’s LNA air-force and the absence of a Western no-fly zone (as was implemented during the anti-Qaddafist revolution) leave open the possibility that new aircraft could be flown in by IS operatives, giving the extremists an air element for use in combat operations or suicide bombings against civilian targets, possibly even beyond Libya’s borders.