Andrew McGregor

AIS Historical Perspective

January 27, 2026

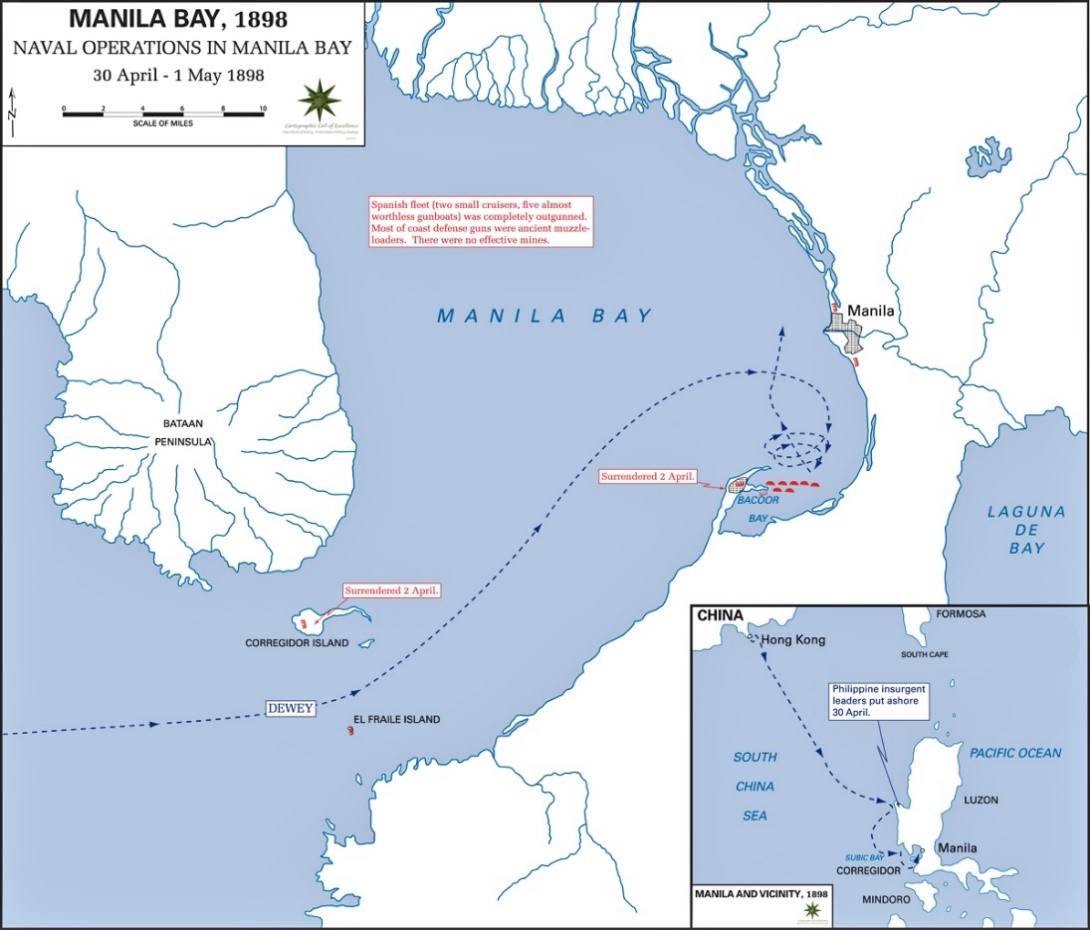

When America went to war with Spain in 1898, its focus was primarily on Cuba, and secondarily on the Caribbean as a whole. While a plan existed to take the war to the Spanish mainland, it was never implemented, having little to do with America’s ultimate war aims. 9700 miles away from the Cuban theater of the war, the Philippines, a Spanish colony for over three centuries, remained a strategic afterthought in Washington. Nonetheless, it was in the Philippines that the Americans won their first great battle of the war only days after declaring war on Spain. Commodore George Dewey achieved a decisive victory at Manila Bay when his squadron of modern warships destroyed a decrepit squadron of Spanish ships manned by untrained sailors. The sudden triumph outstripped American planning; with Washington still unsure of next steps. What happened after the battle is rarely remembered today, but involved the arrival at Manila of a superior German fleet whose behavior, intentional or not, was intimidating enough that it brought the United States and Imperial Germany to the brink of war.

The Early German Naval Presence in Asian Waters

After various wars of unification and intense diplomatic negotiations, the southern German states joined the North German Confederation in 1871 to form the new Prussian-led German Empire with Otto von Bismarck and the Hohenzollern royal family at the helm. Before this time, only Brandenburg and Prussia of the German states had made small and ultimately unsuccessful attempts at establishing foreign colonies. Bismarck opposed any shift to European-style overseas colonialism; Prussia had always relied on a powerful land-based military, but had only a weak and tiny navy. Nonetheless, the new empire required an international presence, and by the 1880s Germany was fielding a number of small warships in East Asia and the Pacific as part of the new Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy).

The most prominent of these was the steam frigate SMS Elisabeth, originally commissioned into the North German Federal Navy in 1868 (SMS stands for Seiner Majestät Schiff – German: His Majesty’s Ship). The Elisabeth arrived in the Far East in 1881, where it became the flagship of a naval squadron consisting of the corvettes Stosch, Stein and Leipzig, the gunboat Wolf and its sister-ship Iltis. The squadron was disbanded in 1885, leaving only the Iltis (1878), the gunboat Nautilus (1871) and the Elisabeth, which was transferred to eastern African waters in June 1881. The squadron was reformed as the East Asia Cruiser Squadron in January 1888, but was disbanded again in May as the larger ships were sent to East Africa to support colony building there. By late 1893, only the gunboats Wolf and Iltis remained in Asian waters.

The Iltis began East Asian service in 1880, fighting pirates near Taiwan and protecting German nationals during disturbances on the Chinese coast. The Iltis toured the Philippines, including the Sulu Archipelago, in March 1881. A ship of 490 metric tons, it was armed with two 4.9-inch guns. The Iltis was sent to Korea in 1894 to secure the German embassy at Inchon during the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1896). The gunboat was also present at the Japanese destruction of the Chinese fleet at the Battle of the Yalu River. In July 1896, the Iltis was ordered to Tsingtao to investigate the suitability of the northern Chinese port for a permanent German naval station, but a powerful storm broke the ship on a reef, with the loss of 71 members of its crew.

The German East Asia Cruiser Squadron in 1898

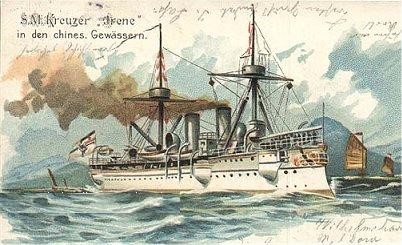

At the beginning of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), the protected cruiser Irene was sent to Asia to become the flagship of the newly formed East Asia Cruiser Squadron (Kreuzerdivision in Ostasien) under Rear Admiral Paul Hoffman. In 1895, several older ships were sent home as the Iltis and Irene were joined by the Irene’s sister-ship Prinzess Wilhelm, the armored cruiser Kaiser (1874) and its sister-ship Deutschland (1874), the protected cruiser Kaiserin Augusta (1892) the unprotected cruiser Cormoran (1893), the gunboat Gefion (1893) and the steam corvette Arcona (1885).

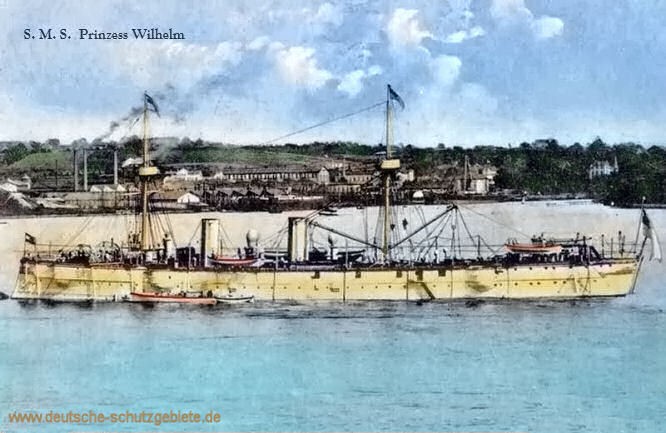

Known to the German navy as “cruiser-corvettes,” the protected cruisers Irene and Prinzess Wilhelm were launched in 1887. The ships, at 4271 metric tons, were highly sea-worthy, but slow, with a typical cruising speed of only nine knots due to a design flaw. Each ship had fourteen Krupp 5.9-inch guns and three torpedo tubes. They were modernized in 1893 before the Irene was sent to East Asia in 1894, with the Prinzess Wilhelm following in 1895.

The British-built ironclad Kaiser’s rigging and sails were removed in 1883 and replaced by two heavy military masts. The ship was rebuilt in 1891-95 as an armored cruiser of 7645 metric tons. The Kaiser was armed with eight 10.2-inch guns in a central casemate battery (soon overtaken by the turret battery design used in later ships) and five torpedo tubes. Its sister-ship Deutschland, also a member of the East Asia squadron, was rebuilt at the same time. They were the last of Germany’s foreign-built capital ships.

The British-built ironclad Kaiser’s rigging and sails were removed in 1883 and replaced by two heavy military masts. The ship was rebuilt in 1891-95 as an armored cruiser of 7645 metric tons. The Kaiser was armed with eight 10.2-inch guns in a central casemate battery (soon overtaken by the turret battery design used in later ships) and five torpedo tubes. Its sister-ship Deutschland, also a member of the East Asia squadron, was rebuilt at the same time. They were the last of Germany’s foreign-built capital ships.

A protected cruiser of 6056 metric tons, the Kaiserin Augusta was launched in 1892. The only one of her class, this unique ship was designed for overseas duty (most German cruisers were designed for dual use overseas or with the home fleet). It joined the East Asia squadron in 1897, armed with 12 5.9-inch guns and five torpedo tubes after an 1896 upgrade. The cruiser’s bow was also reinforced for ramming. The Kaiserin Augusta was considered a fast ship, having crossed the Atlantic at an average speed of 21.5 knots (24.7 miles per hour).

The Gefion was an unprotected gunboat of 3746 metric tons at its launch in 1893. The ship was designed for colonial service or use as a commerce raider in times of war. Armed with ten 4.1inch guns and two torpedo tubes, the Gefion had the greatest range in the German fleet – 3500 knots (4000 miles). It joined the East Asia squadron in May, 1898.

The Cormoran was a Bussard-class unprotected cruiser of 1612 metric tons, independently stationed in the Pacific, but ready to join the East Asia squadron whenever needed. Like the Kaiserin Augusta, it was built solely for overseas duty. Launched in 1892, the ship carried a main battery of eight 10.5-centimeter (4.1 in) guns with two deck-mounted torpedo tubes.

The Arcona was a screw-corvette, one of six ships of the Carola-class equipped with steam and sail for overseas service. The 2662-ton Arcona carried ten 5.9-inch guns and two 3.4-inch guns. The corvette made two visits to the Philippines in 1895 and 1896 to help protect Europeans during local disturbances, landing German marines on its second visit.

Most of the early work of the squadron consisted of surveying, fighting pirates and protecting German nationals and interests in the Pacific and along the Chinese and Korean coasts. Visits to Nagasaki, Formosa, Port Arthur and Vladivostok were common, as well as occasional patrols of the Yangtze River.

Germany Contests Spanish Control of the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Island group is a Pacific Ocean archipelago of some 500 small coral islands. Beginning in 1525, Spain made sporadic attempts to establish sovereignty over the archipelago. When they renewed such attempts in 1885 by adding the region to the Spanish East Indies, German and British trade missions were already active on the islands. Spanish attempts to collect customs duties on German commercial activities saw the arrival of the gunboat Iltis to raise the German flag at Yap (four islands surrounded by a common coral reef) on August 2, 1885, despite the presence of two Spanish warships that ultimately did nothing. Spanish discretion proved the better part of valor; Pope Leo XIII was called on to mediate and conflict was averted when Germany accepted the Pope’s affirmation of Spanish sovereignty. This did not, however, end German interest in the archipelago.

A German Naval Base in China – 1897

The German squadron used Britain’s Hong Kong harbor as a base, but this arrangement was unsatisfactory for several reasons. Thus, a “German Hong Kong” was sought. Numerous ideas were advanced and rejected, including the Kaiser’s suggestion of a joint German/Japanese occupation of Taiwan (this would have proved interesting when the two nations became enemies in 1914). Another possibility was China’s Bay of Jiaozhou; the surrounding region of Shandong (where German missionaries were already active) was rich in coal and iron ore.

Tirpitz took over the East Asia Squadron in June 1896, tasked with finding a permanent base for his itinerant fleet on the Chinese coast. When China refused Germany’s request for a naval port, the Kaiser ordered plans to be made for a takeover of Jiaozhou Bay and the fishing village of Tsingtao (or Quindao, now a city of over 7 million people with a historical district of German colonial-era buildings). After Admiral Tirpitz returned to Germany to become the architect of the German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte), his successor, Rear Admiral Otto von Diederich (appointed June 1897) failed in his efforts to negotiate the German Navy’s use of China’s Kiaochou Bay in June 1897.

A pretext for occupation opened up in November 1897, when two German Catholic missionaries were publicly slaughtered in Shandong. Kaiser Wilhelm styled himself as the personal protector of the mission, and immediately ordered the East Asia Cruiser Squadron into action, against the advice of Tirpitz. The Kaiser, Prinzess Wilhelm and Cormoran took part in the capture of Kiaochou Bay on November 14, 1897 (Irene was in dry-dock at the time).

The German landing party took only two hours to seize Kiaochou and drive out its commander, General Chang, who was put under house arrest. An attempt organized by General Chang from his home to retake the port two weeks later was repulsed by the guns of the Kaiser and the Prinzess Wilhelm. Chang was sent under guard to the Prinzess Wilhelm. Marines of the Seebataillon arrived in January 1898 to consolidate control.

On March 6, 1898, Germany signed a 99-year lease with China for Shandong, without rent. The region came under the authority of the Imperial Navy rather than the usual colonial administration of the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

German Interest in the Philippines

In the 1860s, Prussian merchants and gunrunners became involved with the Muslim sultan of the Sulu Archipelago, which was under blockade by the Spanish, who claimed the territory in the south Philippines. After German unification in 1871, Madrid feared the newly emergent German Empire intended to take the Sulu Archipelago or even the entire Philippines and began seizing German merchant ships headed to the archipelago, some of which carried cargoes of old muskets and ammunition destined for Muslim rebels. The result of this minor crisis was twofold: a growing interest in Filipino affairs in Berlin and a realization that a growing German presence in the Asia/Pacific region required greater naval support than just the old Prussian steam corvette Nymphe, a veteran of wars against Denmark and France and Germany’s lone ship in the vast Pacific. In 1873, the Nymphe visited the sultan of the Sulu Archipelago, who asked for his realm to become a protectorate of the German Empire to free Sulu from Spanish rule. When the request reached Berlin, it was rejected by Bismarck, who replied pragmatically that the German navy was still too weak for Berlin to become involved in such projects. Despite this, some in the German foreign office would remember the sultan’s appeal over twenty years later when it suddenly became of importance.

When the Philippine Revolution broke out in August 1896, the cruiser Arcona was sent to Manila to protect German residents and interests, provoking new suspicions that Germany had designs on the Spanish colony. The Arcona was relieved by the Irene on December 25. Days later, the Spanish executed José Rizal, a German-educated Filipino revolutionary with many German connections who the Spanish believed was in favor of a German takeover of the colony. Though his family pleaded for German intervention, Tirpitz declined and the Irene left on January 3, 1897. When other revolutionaries petitioned for a German protectorate, Wilhelm became convinced there was popular demand in the Philippines for German sovereignty. The Kaiser was alarmed in March 1898 when the German consul in Hong Kong reported American preparations for an assault on Manila, which Wilhelm had already decided should belong to Germany. This attitude on the part of the emperor himself might have contributed to the decision to send an oversized naval representation to Manila at the time of the American attack. Direct action in support of the Spanish was not favored due to differences in Berlin over the power of the Americans. Nonetheless, the Kaiser believed the Philippines should not come under the control of a foreign power without Germany receiving some form of compensation.

That the Germans were serious about expansion in the Asia/Pacific was demonstrated when it was decided to double the strength of the German naval deployment in the region. The Kaiser was delighted with his new acquisition in China and sent out a second division of the East Asia Cruiser Squadron under the command of his brother, Prince Heinrich. Consisting of the flagship Deutschland, the Kaiserin Augusta and the Gefion, the squadron left for China on December 15, 1897, with the Kaiser instructing them: “Should anyone seek to hinder you in the proper exercise of our legitimate rights, go for them with a mailed fist.” The squadron arrived in Tsingtau harbor on May 5, 1898.

The German consul in Manila believed the Filipino insurgents were open to the establishment of a kingdom, possibly with a German prince at its helm. Bernhard von Bülow, the aristocratic German foreign secretary, disputed the consul’s report and informed the Kaiser that this scenario was unlikely and could create conflict with both Britain and America, something the Kaiser did not want under any circumstances. German diplomats suggested to their American counterparts that an American takeover of the Philippines might require German compensation, possibly in the form of coaling stations or harbors in the Sulu archipelago, where Germany had longstanding interests. Possible sites for German bases in the archipelago included Port Dalrymple on Jolo Island and Isabela on Basilan Island. German diplomats tried but failed to persuade Washington that Sulu had been a Prussian protectorate since 1873.

Outbreak of the Spanish-American War

Spain, once the world’s greatest imperial power, was reduced by the late 19th century to minor possessions in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific, the most valuable of which were Cuba and the Philippines. Spain’s much-diminished army struggled to hold on in the face of rebellions in all its colonies, while its overseas fleet consisted mainly of outdated, poorly maintained ships capable of colonial duty but little else. During the three centuries of Spanish rule in the Philippines, military mutinies were a regular occurrence, usually happening in response to Spanish abuses of their own locally-raised troops or Filipino civilians.

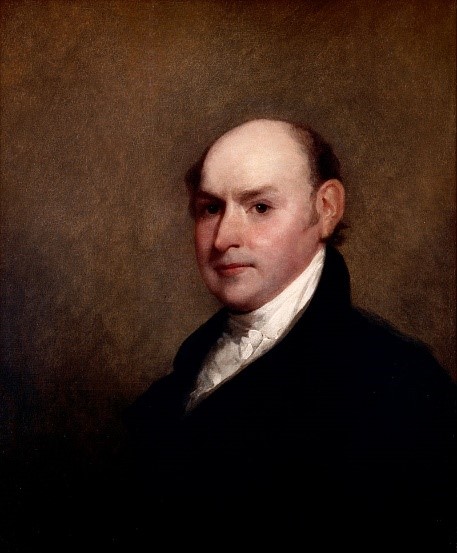

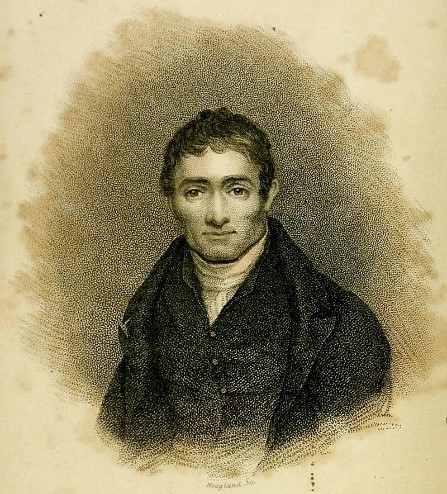

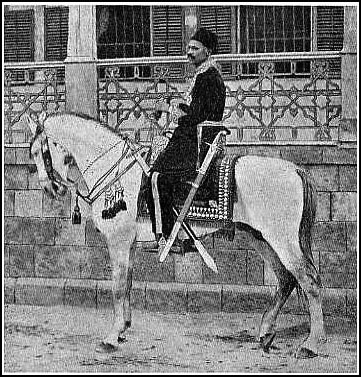

Spanish Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón

Spanish Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón

In August 1896, a fractious nationalist group called Katipunan launched the Filipino Revolution. By 1897, the movement was still unsuccessful in its independence campaign, and the revolution’s leaders (including leader Emilio Aguinaldo) came to an arrangement with the Spanish; in exchange for amnesty and a monetary indemnity, they agreed to exile in Hong Kong. Future Spanish dictator Lieutenant Colonel Miguel Primo de Rivera went with them as hostage for the indemnity payment.

The Battle of Manila Bay

Following the Maine incident in Havana and exaggerated claims of Spanish colonial atrocities repeated in the American press, Washington declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898. In a war largely engineered by imperially-minded political opportunists with the support of a jingoistic press, the United States embarked on a military campaign to seize Spain’s overseas possessions (with the exception of its African colonies).

The Battle of Manila Bay, by Ildefonso Sanz Doménech

Shortly after the declaration of war, the US Asiatic Squadron left Hong Kong for Manila to attack the Spanish squadron of decaying ships based there. The American squadron, commanded by US Civil War veteran Commodore George Dewey, had no permanent base in the East, frequenting Chinese and Japanese ports to supply itself.

The US Asiatic Squadron included four protected cruisers: the flagship Olympia (1892, 5870 tons, four 8-inch guns, 10 5-inch guns), the Baltimore (1888, 4600 tons, four 8-inch guns, six 6-inch guns), the Raleigh (1892, 3200 tons, one 6-inch gun, ten 5-inch guns) and the Boston (1884, 3200 tons, two 8-inch guns, six 6-inch guns). There were also two smaller gunboats, the Concord and Petrel, the McCulloch, a revenue cutter, and a collier and transport ship.

Spanish Cruiser Reina Cristina (1887)

Spanish Cruiser Reina Cristina (1887)

The much weaker Spanish squadron was led by its flagship, the Reina Cristina (1887), an unprotected cruiser of 3,042 tons (smaller than all four American cruisers), with six 6.4-inch guns that became the main target of American fire when the battle began. The Reina Cristina was supported by the Castilla (1881), an unprotected cruiser of 3,289 tons, with a ram bow and four 5.9-inch and two 4.7-inch guns. Unfortunately, the Castilla was largely immobile due to problems with her propeller shaft and was forced to fight the battle while still at anchor until she was sunk. The Reina Cristina was destroyed by shellfire with heavy loss of life before being scuttled.

Other Spanish ships included:

- The unprotected cruiser Don Antonio de Ulloa (1887), 1152 tons, with only two 4.7-inch guns on the starboard side, the port side guns having been dismantled for use in shore batteries. The Don Antonio had been sent to the Caroline Islands in 1890 to fend off German cruisers. By 1898, however, her machinery was in bad repair and the ship was unable to move during the battle, allowing it to be completely destroyed by the American guns.

- Don Juan de Austria (1897) was an unprotected cruiser of 1152 metric tons, equipped with four 4.7-inch guns. She was badly damaged by American fire before being scuttled. The ship was later raised to become the USS Don Juan de Austria.

- The protected cruiser Isla de Cuba (1886) displaced 1053 metric tons and carried six 4.7-inch guns. She was scuttled to prevent capture during the battle after Admiral Montojo moved his flag to her after the destruction of the Reina Cristina. The cruiser was later raised and put back to work fighting Filipino rebels as the USS Isla de Cuba before being sold to the Venezuelan Navy, where she served until 1940. The Isla de Cuba’s sister-ship, the Isla de Luzón, suffered multiple hits in the battle and was likewise scuttled and refloated to join American service.

- The Marques del Duero (1875), a gunboat/despatch ship of 492 metric tons, with one 6.4-inch and two 4.7-inch guns, was the oldest ship in the Spanish squadron. Badly damaged in the battle, it was scuttled before being raised for a short career as the USS P-17.

Three small Spanish gunboats in the area did not take part in the battle, while the guns of an unprotected cruiser, the Velasco, had already been moved to shore batteries that played little part in the battle, the American ships operating mostly out of range. Many of the Spanish ships had torpedo tubes, but there were no torpedoes available.

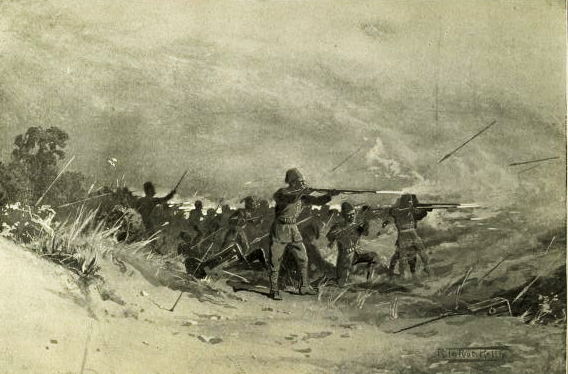

The seven-hour battle that followed the arrival of the US squadron was so one-sided that the Americans were able to take a break for breakfast half-way through before returning to the destruction of the Spanish ships. Damage to the American ships was extremely light and only one fatality was reported. The Spanish suffered 77 dead and over 270 wounded; by the end of the encounter not a single Spanish ship remained afloat of those that had taken part in the battle.

Despite the personal valor he displayed at the head of his decrepit fleet, the Spanish squadron’s commander, Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón, was court-martialled, dismissed from the navy and briefly imprisoned on his return to Spain. A report from Admiral Dewey testifying to his gallantry in the unequal battle was of little help.

After the Battle of Manila Bay

After the Battle of Manila Bay

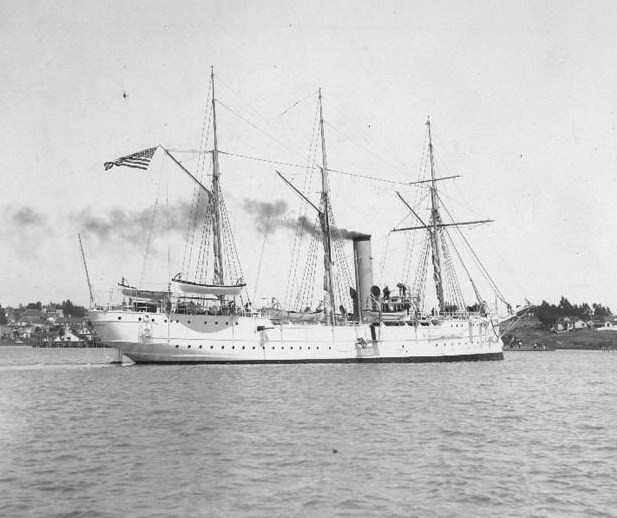

The speed of the American naval victory in Manila had outstripped American planning, with the question of American intentions in the Philippines remaining unanswered while Dewey awaited further instructions. It was unclear what Washington intended for the Philippines – independence, American occupation, continued Spanish control with the payment of an indemnity, annexation, a US naval withdrawal, or the American sale of the islands to a third party (most likely Britain). Meanwhile, Filipino revolutionaries led by Aguinaldo continued their campaign against Spanish troops. In exile in Hong Kong since 1897, Aguinaldo had been returned by Dewey to Manila on the revenue cutter USS McCulloch on May 19. As Dewey awaited further orders, it seemed an opportune time for Germany to position naval assets to exploit this uncertainty and perhaps influence developments to Germany’s advantage. The SMS Irene and SMS Cormoran were the first German ships to arrive in Manila on May 6 and May 9, respectively.

The German consul in Manila reported that the Spanish governor general was willing to accept turning the city over to the commanders of the various European neutral warships that gathered in the harbor to observe the battle and protect their nationals and interests in the Philippines, but was unable to persuade Admiral Diederichs to take the lead in such an action without a directive from Berlin. Meanwhile, the German Foreign Office was following the Kaiser’s order to avoid unduly antagonizing the Americans and forcing them into an alliance with Britain.

The international ships at Manila were typical of the type generally used in observer situations. These included the HMS Immortalité (1887), an armored cruiser of little note, and HMS Linnet (1880), a gunboat also of little distinction despite being the sixth ship of its name in the Royal Navy. The French Bruix was an armored cruiser that would eventually be used against German forces in the Kamerun campaign of 1914-15. The Japanese Ituskushima was a French-built protected cruiser, a poorly designed ship with a single 12.6-inch gun whose recoil was too much for the vessel to handle with any ease. Despite her deficiencies, she fought in the 1894 Battle of the Yalu River against China and again in the world-changing 1905 Battle of Tsushima against the Russian fleet.

On June 2, 1898, the Kaiser issued Admiral Diederichs’ main order: “Sail to Manila [with the East Asia Squadron] in order to form a personal opinion about Spain’s situation there, the population’s mood, and the foreign influence on the political reorganization of the Philippines.” Tirpitz added that strict neutrality should be observed to protect German interests elsewhere in the Pacific. There was nothing to suggest that Diederichs was to support the Spanish, back the rebels or otherwise interfere in the American campaign, whose goals were still frustratingly unclear. Nonetheless, the presence of a strong German squadron would enable the Germans to exploit an American withdrawal should that happen.

Dewey’s ammunition was seriously depleted after the battle and the commodore’s nerves were on edge due to the intense summer heat and the absence of cable communications with his superiors – messages needed to be sent by ship to the telegraph station at Hong Kong, with the reply coming back the same way, a process of roughly one week.

The German troop transport Darmstadt arrived on June 6 with 1400 soldiers and a collier ship. The Americans, who would have no troops of their own in Manila for another six weeks, were duly shocked by what seemed a German intention to seize their prize. In reality, the German troops were headed to Tsingtau and the Darmstadt had only stopped at Manila to provide relief crews for the Irene and Cormoran. Dewey was greatly relieved when the transport left 72 hours after arriving, but alarms had once more been sounded by what appeared to be another effort to intimidate the victorious American squadron.

Rebuilt SMS Deutschland as armored cruiser in 1898 at Port Arthur. Compare with photo of sister-ship Kaiser before modernization. The Kaiser was modernized at the same time.

Rebuilt SMS Deutschland as armored cruiser in 1898 at Port Arthur. Compare with photo of sister-ship Kaiser before modernization. The Kaiser was modernized at the same time.

The rest of the German squadron arrived on June 12, the same day Aguinaldo’s rebels declared the independence of the Philippines. By this time, there were five German warships gathered at Manila, the Prinzess Wilhelm, Kaiser, Irene, Kaiserin Augusta and Cormoran (the Deutschland, Gefion, and Arcona remained in Chinese waters). The size and power of this squadron was significantly out of proportion for what was required for observation purposes. Both the Kaiser and the Kaiserin Augusta were larger than any of Dewey’s ships and rumors in Manila maintained that Diederichs, who was senior in rank to Dewey (another oddity for an observer mission), had arrived to support the Spanish.

While the Americans fretted over the size of the German squadron and its forceful commander, Diederichs was, by June 25, actually sending official reports to Berlin suggesting his squadron was far too large and that a figure of his high rank should never have been sent to deal with Dewey, a mere commodore.

The actions of the German squadron seemed to tell a different story, however, and appear to have involved some degree of intimidation, with German ships ignoring the American blockade of the bay, coming and going at will during the night, flashing powerful searchlights at random and sending a steady stream of communications by signal lamp, keeping the American squadron constantly on edge. German sailors even seized a lighthouse and various Spanish onshore facilities without explanation.

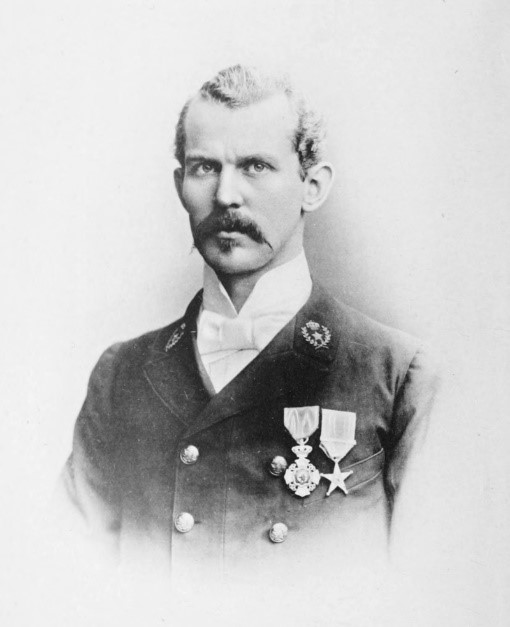

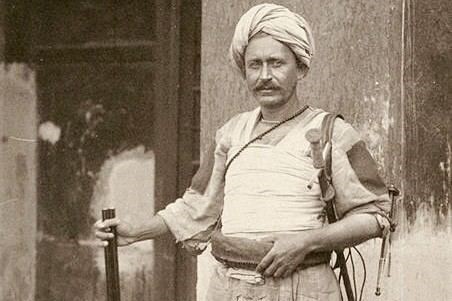

Rear Admiral Otto von Diederichs

Rear Admiral Otto von Diederichs

Most alarming to the Americans, however, was a visit by Diederichs to the Spanish governor general of the Philippines, Basilio Augustín y Dávila Augustín, and a return visit by the governor to the Kaiser. Though this unnerved Dewey, it emerged later that Diederichs used these talks to explain to the governor that he could not take any action in support of a Spanish proposal to mollify the rebels by establishing a looser Spanish protectorate over the Philippines guaranteed by Germany (perceived to be friendly to the Filipinos) without orders from Berlin. If Dewey had known the direction and tenor of the talks, he may have hosted them himself. Instead, Dewey called on Diederichs to have him explain the presence and activities of the German squadron, to which Diederichs replied: “I am here, sir, by order of the Kaiser.” Like many other exchanges with the Germans, this response seemed curt, unilluminating and slightly menacing.

Diederichs also ordered the German consul and a flag-lieutenant to meet with the Filipino rebels. The admiral reported these talks in a top-secret message to Berlin. Feeling independence was near, the rebels initially informed the Germans they no longer had interest in a German protectorate. Diederichs, who believed in the inevitable collapse of a Filipino government, suggested patience until that time, while warning the rebels might be trying to play the Germans against the Americans. Further talks revealed that Aguinaldo was personally interested in close ties to Germany (possibly even as a protectorate) once independence had been achieved. The rebel government attempted to send an envoy, Antonio Regidor, to Berlin to enquire about a German protectorate, but the visit was suspended by Wilhelm until independence was achieved. However, the size of the German squadron at Manila also confused the revolutionaries, who believed it could only be there to support the Spanish occupation. Meanwhile, Admiral Diederichs was reporting that he could discern no reliable support in the Philippines for a German protectorate.

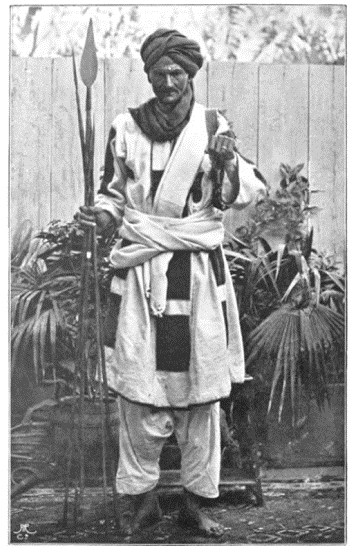

The US Revenue Cutter McCulloch

The US Revenue Cutter McCulloch

On June 27, an officer from the American revenue cutter McCulloch boarded the Irene in daytime, a provocative action that revealed Dewey’s anxiety about the German ships. Identification boardings at night when ships were difficult to identify were considered acceptable at the time, while daytime boardings were considered insulting and unnecessary. Despite this Diederichs at all times ordered his squadron to accept night-time boardings by American officers. The American press inflamed the incident by claiming the McCulloch had fired a shot across the Irene’s bows to force her to stop. Further dubious incidents involving shots being fired across the bows of German warships were cited in the American press, eventually finding their way into the historical record. Diederichs, however, reported to the Kaiser that no shots had been fired at German ships, describing such reports as inventions of the anti-German American press.

The New York Times (June 30, 1898) questioned the purpose of the oversize German squadron in Manila:

The apparatus she has provided is quite out of proportion to the object to be attained. There may be forty or fifty German subjects doing business in Manila. … A single man-of-war could accommodate the entire German population of Manila. Yet the provision that Germany has made is a squadron composed, at last accounts, of five vessels, and superior to the American squadron which destroyed the Spanish fleet and which now holds Manila under its guns. We should be very simple to believe that this force has been assembled merely to rescue German inhabitants from the fury of Auguinaldo.

There can be no doubt of the unofficial American view of the assemblage of a German squadron in Manila Bay. It is that that assemblage is unmannerly and provocative, and that it is meant not to protect existing German interests but to find new interests to protect.

German public opinion during the war was generally supportive of Spain, in contrast to the government’s official (but undeclared) neutrality. The German press began to weigh in against the Americans; these reports aggravated the situation when they were translated and reprinted in American newspapers.

On July 5, the Irene was ordered south to Subic Bay (later an American naval base, but held at this time by Filipino revolutionaries) to explore its usefulness as a harbor and to evacuate noncombatants and severely wounded troops from a beleaguered Spanish garrison on Isla Grande. While off the island, the Irene encountered the Filipinas, a merchant steamer flying the insurgent flag and having every appearance of preparing to deliver an attack on Isla Grande. The Germans, who had not yet evacuated the noncombatants, ordered the insurgents to haul down their flag, still officially unrecognized by any state. After the Filipinas slipped away in the night, its captain reported to Aguinaldo and the still pro-rebel Americans that the Irene had interfered with their attack on the Spanish. Dewey, believing this to be a violation of neutrality, sent the Raleigh and Concord to investigate, but these arrived only in time to see the departure of the Irene. The German cruiser’s action, never explained to the Americans, was interpreted by the latter and by Aguinaldo’s rebel forces as naval support of the Spanish garrison.

Efforts to improve relations only made things worse. Dewey sent an officer to complain to Diederichs about blockade violations but the officer came away reassured by the admiral’s sincerity in stating his desire not to interfere with American operations. A July 10 return visit to Dewey by a German officer went well until the officer complained the Irene had been illegally stopped and boarded. Dewey exploded, threatening to stop every ship and fire at any that resisted, shouting “If Germany wants war, alright – we are ready!” When he continued in this vein, the German officer chose to leave and report to Diederichs. Though the German admiral decided not to make an issue of Dewey’s outburst, tensions between the two squadrons were now at a peak. With more anger than discretion, Dewey unwisely revealed plans to engage the German squadron to American reporters. The growing pressure was somewhat alleviated when the Americans learned Diederichs had ordered the Irene to leave the Philippines on July 9, leaving four German ships at Manila. A growing correspondence between Dewey and Diederichs also helped calm the standoff through July.

The Spanish Relief Fleet

Spain’s best ships were in its home fleet, and a plan was formed to have them steam to America and bombard cities on the US coast. As well as causing panic in the enemy’s homeland, it would also help relieve the American blockade of Cuba and allow the Spanish naval squadron trapped there to take to sea. The plan did not receive approval from the pro-American British, who regarded the Atlantic at the time as their own Mare Nostrum.

The bombardment of the American coast was abandoned and the squadron ordered on June 16 to steam to Manila to restore Spanish control of the Philippines. Known as “the Second Squadron,” the ships came under the command of Admiral Manuel de la Cámara y Livermore, a veteran of the War of the Pacific (which pitted Spain against Peru and Chile, 1865-1866), the First Cuban War (1868-1878) and the First Rif War, fought in Spanish Morocco (1893-1894). Cámara knew the way to the Philippines, having led the “Black Squadron” of three Spanish warships to Manila in 1890.

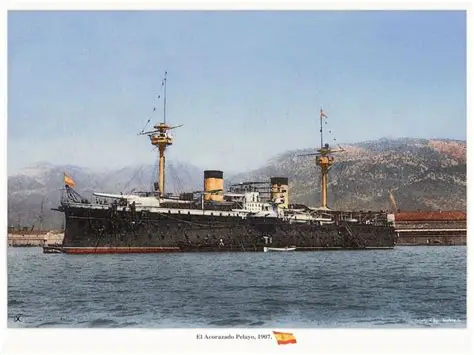

Cámara’s relief squadron included the battleship Pelayo (1888, partially rebuilt just before deployment) with two 12.6-inch guns and two 11-inch guns, and the brand-new armored cruiser Emperador Carlos V, with 11-inch guns. With support ships, this squadron would bring into play far more powerful weapons than the 8-inch and 6-inch guns of the four protected cruisers of the American Asiatic Squadron. With America’s most powerful ships deployed in the more important Caribbean theater of the war, a desperate admiralty sent the US monitor Monterey (1891) with two 12-inch guns, two ten-inch guns and a ram to Manila from San Francisco on June 11. It was followed by the monitor USS Monadnock (1883), with four ten-inch guns on June 23. Though the monitors, with very low freeboards, were designed for use in coastal waters or rivers, they both survived harrowing two-month crossings of the Pacific. They would remain in the Philippines until 1899.

Spanish Cruiser Emperador Carlos V in the Suez Canal

Spanish Cruiser Emperador Carlos V in the Suez Canal

The Spanish Second Squadron passed through the Suez Canal after several days of negotiations with British authorities and reached the Red Sea by July 7, but was ordered to return home following the American destruction of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron at Santiago, Cuba on July 3, 1898. Four Spanish cruisers had stood no chance against four American battleships and two armored cruisers. This created an opening for the US to implement plans to raid the Spanish coast with the battleships Iowa and Oregon and the cruiser Brooklyn. The American attack was called off once the powerful Spanish ships turned for home, where Cámara’s squadron was disbanded on July 25, 1898.

The End of Uncertainty

American intentions in the Philippines started to become clear when US troops began to arrive. The first American ground force of 2700 men landed on July 1, 1898. Further troopships arrived at Manila on July 17 and again on July 31. Instead of aggravating the situation, their arrival confirmed that the Americans planned a military occupation, a development that would leave little room for German expansion in the islands. By the end of July, the German foreign ministry informed Washington that their ships never intended to interfere with American operations and a large squadron had only been sent in response to public pressure in Germany to defend German interests in the Philippines.

USS Monterey Crossing the Pacific, 1898

USS Monterey Crossing the Pacific, 1898

The US monitor Monterey arrived on August 4; when the monitor Monadnock sailed into Manila Bay on August 16, the American squadron was finally stronger than their German counterparts.

There was, strangely, to be one more incident that was little noted at the time but later grew in stature into an almost legendary confrontation. A secret armistice was agreed upon by the Americans and the Spanish on August 12. A mock battle was arranged for the next day to allow the Spanish to save face and avoid a potential slaughter by the Filipino insurgents by surrendering to the Americans instead.

As the American ships moved from nearby Cavite to positions off Manila to shell the city on August 13, the two British cruisers moved into a position between the Americans and the four remaining German ships. Though no-one at the time thought it was anything other than the British ships moving into a better observation point (with little regard for the view of the Germans), it was later interpreted as the pro-American British preventing an imminent attack on the American flank by the German squadron. In fact, neither the British nor German ships were cleared for action and the only German movement was to shift the Kaiser slightly after the British ships blocked the German flagship’s view of the American bombardment. With the exception of one American ship, the US squadron followed Dewey’s order to fire only on low-value or uninhabited targets.

American infantry advanced into the city, with some commanders who had not been informed of the full plan surprised by the light resistance they encountered. Aguinaldo’s rebels had been warned by the Americans to stay out of Manila during American operations there, but joined the American advance instead, ignoring Spanish flags of truce and forcing the Spanish to resist in earnest for their own survival. As a result, 19 Americans and 49 Spaniards were dead by the end of the “mock battle.”

Following the shelling of the city, the Kaiserin Augusta sailed away with the Spanish Governor General, though the ship’s captain later claimed he did so with American permission. Diederichs departed Manila for Batavia on August 21 aboard the Kaiser. The rest of the German squadron left for Mariveles (Bataan Province), leaving only the Prinzess Wilhelm on station to protect German nationals.

Aftermath

Dewey appears to have been more alarmed by the presence of the German squadron at Manila than Washington. Though both the German and American press contributed to the belief that a confrontation was imminent, there was little appetite for such in both Washington and Berlin. The German presence was opportunistic and designed to exploit a possible collapse of the Philippines in concert with other “sea-powers” if such a course arose. When the Spanish-American armistice was signed on August 12, German interest in a Philippines protectorate evaporated and Diederichs was ordered to the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia) to celebrate the coronation of the Queen of the Netherlands. German attention quickly turned to obtaining Spain’s other possessions in the Pacific. American diplomats were informed that if the US did not object to this activity, Germany would abandon any claims to the Sulu Archipelago. This proved agreeable to both sides. Meanwhile, the December 10, 1898 Treaty of Paris forced Spain to sell the Philippines to the US for $20 million. On February 4, 1889, the US Senate voted for the full annexation of the Philippines.

Despite his rapprochement with Diederichs, Dewey appears to have remained angered by his confrontation with the Germans, telling an American correspondent during his trip home that America’s next war would be with Germany. He continued to express anti-German sentiments on his return, earning a reprimand from President Roosevelt. Dewey would later tell a French admiral that his biggest mistake at Manila was not sinking the German squadron, a feat that was likely beyond his ability. By April 1899, however, Dewey was ready to admit in a letter to Diederichs that their differences had been largely manufactured by the press. Diederichs was recalled to Berlin in 1899 to become the new chief of the admiralty staff.

Even after Washington betrayed the Filipino revolutionaries and decided to keep the entire Philippines as a colony, the German Colonial Society advocated a German occupation of the island of Mindoro, the seventh biggest island in the Philippines, just south of Luzon. Mindoro had fine harbors, but had never come under complete Spanish control. It took US troops over two years to crush local resistance on the island and the ambitions of the German Colonial Society eventually came to nothing.

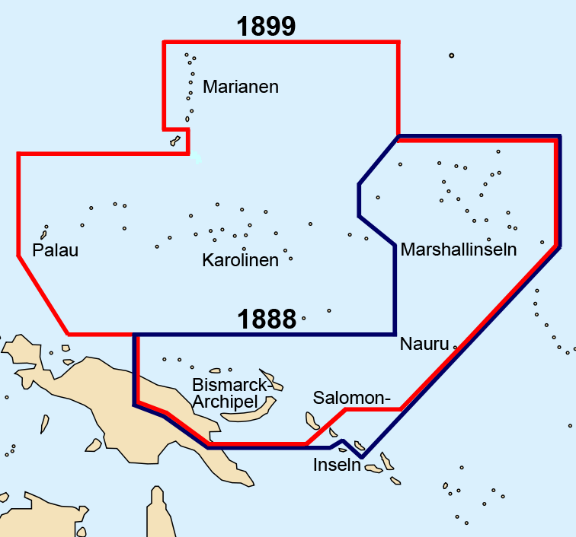

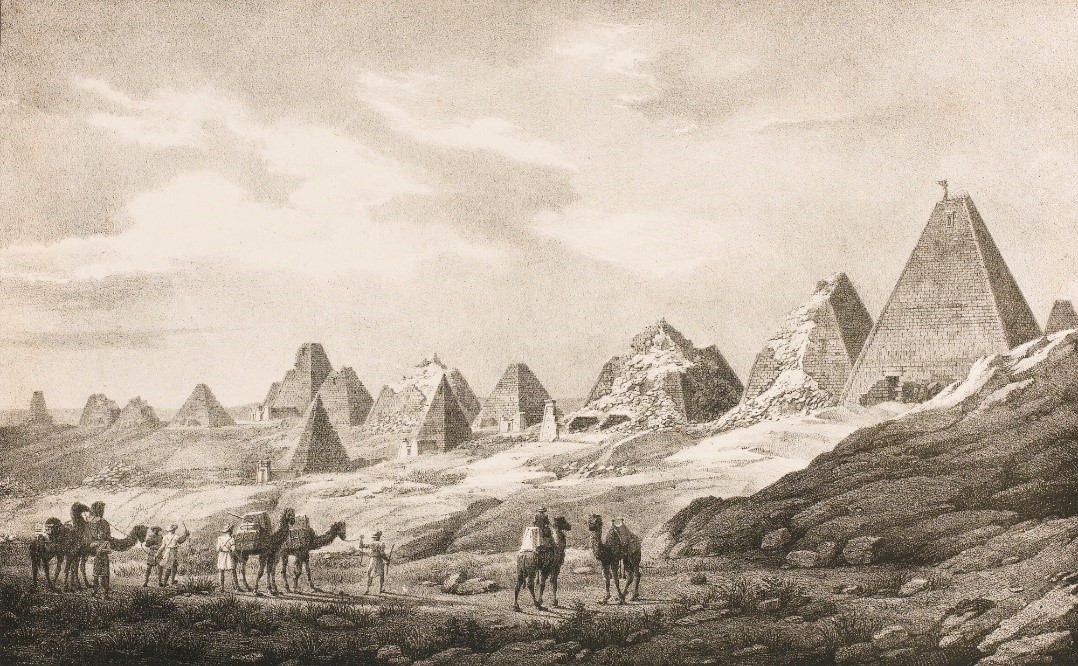

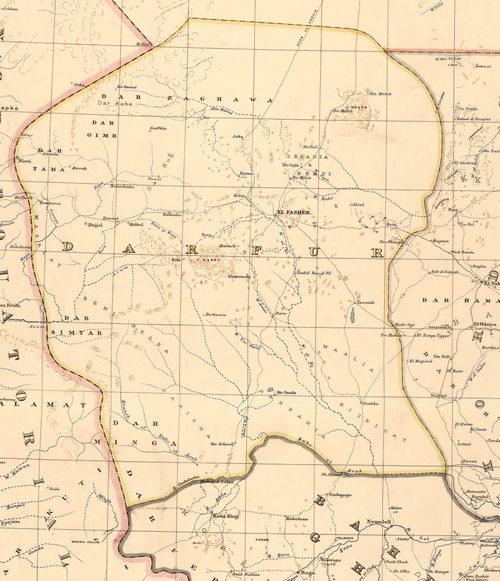

The German Empire in the Pacific (Chrischerf).

The German Empire in the Pacific (Chrischerf).

Though Germany had missed out on the Philippines, it still benefited from the Spanish defeat through the German-Spanish Treaty of 1899, in which Spain sold the Pacific island chains of the Carolines, the Palau Islands and the Northern Marianas to Berlin for 25 million pesetas. These roughly 6000 islands were placed under the administration of German New Guinea, giving Germany vast, if relatively unproductive, holdings in the Pacific. The new gunboat SMS Jaguar was sent on a flag-raising tour of Germany’s new possessions.

After the Manila incident there would be many more operations by the German East Asian Squadron before its 1914 triumph over a British fleet at Colonel off the west coast of South America and its subsequent destruction by a second British fleet at the Battle of the Falklands. These operations included the Battle of the Taku Forts, the suppression of the Boxer Uprising and the crushing of rebellions against German rule in the Caroline Islands and German Samoa. After the outbreak of the Great War, the fleet’s German gunboats (including the Iltis and Jaguar) remained at Tsingtao to battle the 1914 Japanese/British offensive that finally expelled the Germans from China.

At a time when communications with home were impossibly slow even in tense situations that demanded immediate decisions, Diederichs had somehow managed to make a display of Germany’s new-found overseas power while at the same time showing just enough restraint and diplomatic acumen to avoid a war with the United States that no-one in Berlin wanted, despite the decision to send an entire German squadron to Manila when a lone gunboat might have sufficed.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bailey, Thomas A: (1939) “Dewey and the Germans at Manila Bay,” The American Historical Review 45(1), October 1939, pp. 59-81.

Blackley, Andrew K: (2024) “Neither Cruiser nor Gunboat: The USS Monterey,” Naval History 38(4), United States Naval Institute, August 2024.

Bönker, Dirk: (2013) “Global Politics and Germany’s Destiny ‘from an East Asian Perspective’: Alfred von Tirpitz and the Making of Wilhelmine Navalism,” Central European History 46(1), March 2013, pp. 61-96.

Dewey, George: (1913) Autobiography of George Dewey, Admiral of the Navy, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

Dodson, Aidan: (2016). The Kaiser’s Battlefleet: German Capital Ships 1871–1918. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley.

Dodson, Aidan: (2017) “After the Kaiser: The Imperial German Navy’s Light Cruisers after 1918,” In John Jordan (ed.): Warship 2017, Conway, London, pp. 140–159.

Dodson, Aidan, and Dirk Nottelmann: (2021) The Kaiser’s Cruisers 1871–1918, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis.

Ellicott, JM: (1955) “The Cold War Between Von Diederichs and Dewey in Manila Bay,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 85(11), November 1955, pp. 1236-1239.

Gardiner, Robert; Roger Chesneau and Eugene M Kolesnik (eds.): (1979) Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1860-1905, Conway Maritime Press, Greenwich CT.

Gottschall, Terrell D: (2003) By Order of the Kaiser, Otto von Diederichs and the Rise of the Imperial German Navy 1865–1902, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis.

Gröner, Erich: (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945 Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis.

Guerrero, Leon MA: (1961) “The Kaiser and the Philippines,” Philippine Studies 9(4), October 1961, pp. 584-600.

Herwig, Holger (1980): “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918, Humanity Books, Amherst.

Hezel Francis, X: (2003). Strangers in Their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Hildebrand, Hans H, Albert Röhr and Hans-Otto Steinmetz: (1993) Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart Vol. 1, Mundus Verlag, Ratingen.

Nottelmann, Dirk & Sullivan, David M: (2023). From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Battleship, 1864–1918. Warwick: Helion & Company

Sargent, Commander Nathan (ed.): (1947) Admiral Dewey and the Manila Campaign, Naval Historical Foundation, Washington DC.

Schult, Volker: (2002) “Revolutionaries and Admirals: The German East Asia Squadron in Manila Bay,” Philippine Studies 50(4), pp. 496-511.

Schult, Volker, and Karl-Heinz Wionzek (eds.): (2017) The German and Austrian Navies in the Philippines, and Their Role in the Spanish-American War of 1898: A collection of original documents, National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP).

Shippee, Lester Burrell: (1925) “Germany and the Spanish-American War,” The American Historical Review 30(4), July 1925, pp. 754-777.

Sondhaus, Lawrence” (1997) Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press

Van Dijk, Kees: (2015) “The Scramble for China: The Bay of Jiaozhou and Port Arthur,” in: Tak-Wing Ngo (ed.): Pacific Strife, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 295-316.

Wionzek, Karl-Heinz (ed.): (2000) Germany, the Philippines and the Spanish-American War. Four Accounts by Officers of the Imperial German Navy, National Historical Institute, Manila.

Tomb of Roger Vanderberghe, Pau, France (Joel Herbez)

Tomb of Roger Vanderberghe, Pau, France (Joel Herbez)