Andrew McGregor

April 17, 2015

Al-Shabaab’s April 2 attack on Kenya’s Garissa University College that killed 147 non-Muslim students was the latest installment in al-Shabaab’s campaign to force Nairobi to order a withdrawal of the Kenyan Defense Force (KDF) from the Jubaland region of southern Somalia. So far, the Kenyan government has presented an uncoordinated response that has largely focused on Islamist militancy as a foreign problem that is being imported (along with hundreds of thousands of unwanted refugees) across Kenya’s porous border with neighboring Somalia.

KDF Troops in Southern Somalia

KDF Troops in Southern Somalia

Background

The KDF moved into southern Somalia in 2011 as part of Operation Linda Nchi, designed to deter cross-border infiltration of radical Islamists, create a Kenyan-controlled buffer zone in southern Somalia and establish suitable conditions for the return of the massive Somali refugee population dwelling in Kenya’s largely ethnic-Somali North Eastern Province. KDF troops in Somalia joined the larger African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) in February 2012.

In military terms, the KDF presence has exerted a slow but ultimately relentless pressure on Somalia’s al-Shabaab movement. The seizure of the port at Kuday Island (southern Juba region, south of Kismayo) by KDF and Somali National Army (SNA) forces during an amphibious operation on March 22 drove al-Shabaab from its last access point to the sea, dealing the organization a severe blow and leaving it effectively surrounded by hostile forces (Raxanreeb, March 22). Military pressure from AMISOM and financial pressures created by the gradual loss of access to every port prompted a strategic overhaul of the group’s activities. For al-Shabaab, direct confrontations with Somali security forces or the much stronger AMISOM deployment are out; a greater focus on terrorist tactics (including bombings, assassinations and assaults on soft targets by well-armed gunmen) is in. Expelling the KDF is a priority, and the movement is willing to exploit ethnic tensions in Kenya’s North Eastern Province to achieve this goal.

The region’s ethnic-Somali population (belonging largely to the powerful Ogadeni clan) was geographically divided in 1925, when Britain gave the northern half of the region (modern Jubaland) to Italy. The southern half of the region is now Kenya’s North Eastern Province. The division was massively unpopular with the region’s ethnic-Somalis, leading the British to close the region from 1926 to 1934. Dislike of the Kenyan government (dominated by the Kikuyu tribe) erupted into the Shifta War of 1963-1967. Dissatisfaction with the administration has been punctuated by sporadic political violence in the region ever since, the worst example being the 1984 Wagalla Massacre of thousands of ethnic-Somalis by Kenyan security forces. [1]

The Assault on Garissa College University

Kenya’s security forces may have relaxed prematurely after seizing Kismayo, al-Shabaab’s largest port, in 2012. While taking Kismayo fulfilled Nairobi’s objective of creating an autonomous buffer zone (“Jubaland”) between Kenya and the rest of Somalia, it only intensified al-Shabaab’s hatred of Kenya and its determination to retake Somali-inhabited areas of Kenya, even if it means the use of terrorist atrocities targeting Kenyan civilians. The border became no less permeable with the creation of a Kenya-reliant Jubaland administration, yet the Kenyan government continued to neglect border security in the North Eastern Province, where roads and other infrastructure are few and far between.

The attack at Garissa appears to have been well-planned—university administrators said two of the terrorists had posed as students while using a room on campus as a “command center,” complete with food and supplies that appeared to be intended for a long battle (Standard [Nairobi], April 10). Survivors described the attackers as speaking Swahili (Kenya’s main language) rather than Somali (Mail & Guardian [Johannesburg], April 4). Militants told at least one survivor of the attack: “Tell your President to withdraw KDF from Somalia and ensure that North Eastern [province] belongs to Muslims. Garissa must also be part of Somalia and not Kenya” (Standard [Nairobi], April 11).

While helicopters were made available to take the Interior Cabinet Secretary (who routinely assures Kenyans the government is keeping them safe) and the Inspector General of Police to Garissa, the elite counter-terrorist Recce company of the paramilitary General Service Unit (GSU) got stuck in traffic on their way to the airport, where they were transported to Garissa by fixed wing aircraft while their equipment travelled by road (Star [Nairobi], April 11). The aircraft that should have been available to transport the Recce unit was unavailable as it had been used that morning to fly private individuals to Mombasa and pick up the daughter-in-law of police air-wing chief Rogers Mbithi (Daily Nation [Nairobi], April 13; Star [Nairobi], April 15).

This suggests that Kenyan authorities have not absorbed the lessons of the 2013 attack on Nairobi’s Westgate Mall, particularly in regard to having transport available for its rapid response units. In the Westgate incident, Kenya’s elite 40 Rangers Strike Force arrived at the mall from their base at Gilgil (roughly 75 kilometers north of Nairobi) 12 hours after the attack began, and promptly engaged in a gunfight with members of the General Service Unit (GSU), a paramilitary wing of the National Police Service. Action against the terrorists still inside the mall was confused as many members of the police and military devoted themselves to looting the mall rather than rescuing hostages. In response to the resulting public outrage, the Kenyan military sacked and jailed two members of its elite 40 Rangers Strike Force and declared the matter finished (Standard [Nairobi], October 30, 2013).

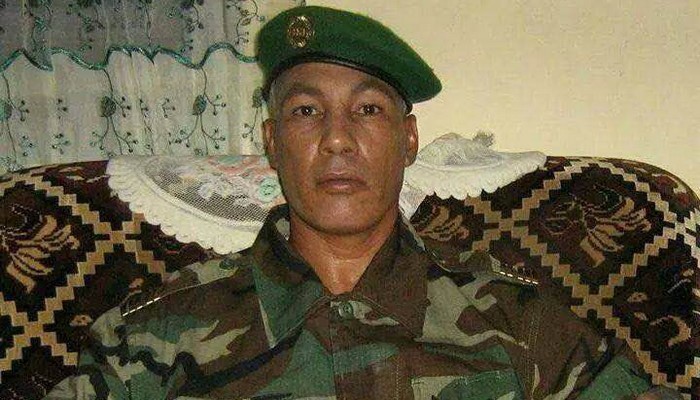

Alleged Attack Planner Mohamed Kuno

Alleged Attack Planner Mohamed Kuno

Though the Kenyan government continues to treat al-Shabaab as an external threat, there is evidence that the radical Islamist threat is an internal problem, albeit one inspired by al-Shabaab. The alleged planner of the attack, Mohamed Kuno (a.k.a. Mohamed Dulyadin; a.k.a. Gamadhere; a.k.a. Shaykh Mohamud), has strong connections to Kenya’s ethnic-Somali community. Kuno worked as a teacher and principal of a madrassa in Garissa from 1997 to 2000, where he is remembered for his religious radicalism before his departure for Somalia (Daily Nation [Nairobi], April 2). Once in Somalia, Kuno acted as a commander in some of the heaviest fighting in Mogadishu, and, for a time, even served in the al-Shabaab-allied Ras Kamboni Brigade under Shaykh Ahmed Mohamed Islam “Madobe,” who ironically is now the Kenyan-backed “president” of Jubaland (Mail & Guardian [Johannesburg], April 4). The former teacher is the prime suspect in the massacre of 28 Kenyan Christians in Mandera County in November 2014 and the killing of a further 36 Christian quarry workers in Mandera in December 2014. At present, Kano is responsible for al-Shabaab operations in Jubaland and Kenya.

In the wake of the attack, opposition leaders continue to demand a KDF withdrawal from Somalia in order to concentrate on border security, suggesting that the United States try to persuade other nations without a common border with Somalia to replace the Kenyan troops (Standard [Nairobi], April 11).

A Failure of Intelligence?

In the border regions, there are few Kenyan intelligence officers from the local ethnic-Somali community, contributing to Kenya’s continued inability to secure its border with Somalia (Standard [Nairobi], April 12). In addition, Kenyan authorities appear to have ignored foreign intelligence reports passed to them:

- Three weeks before the Garissa attack, UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond warned that Kenya was not acting on intelligence information regarding possible terrorist activity—only a day before the Garissa attack, President Kenyatta called British travel advisory warnings on Kenya an attempt “to intimidate us with these threats” (Standard [Nairobi], April 5).

- Iran is reported to have supplied information on March 22 of pending attacks on Kenyan Christians in university areas of Garissa, Nairobi and Mombasa prior to the assault on the Garissa University, where Christians were singled out (Standard [Nairobi], April 12).

- On March 27, Australia issued a warning of an impending terrorist attack in Nairobi (Reuters, March 28).

- According to a student interviewed by Reuters, whose account was corroborated by northern Kenyan MPs, the administration of the Garissa Teacher’s College closed the school days before the attack, telling students that strangers had been spotted in the college and that a terrorist attack might be imminent. This action was not followed by the rest of the campus, which remained open. According to one MP, “Some of us have seen the intelligence reports, and I can assure you they were specific and actionable” (Reuters, April 3).

The Kenyan Response

The KDF’s immediate reaction to the Garissa massacre was to bomb al-Shabaab camps in Somalia, including Camp Shaykh Ismail, Camp Gondodwe, Camp Bardheere and what was described as a major camp in Gedo Region where some 800 militants were based. Though the KDF claimed each base was completely destroyed (unlikely considering that only ten aircraft were used and the cloudy conditions at the time), al-Shabaab made the equally unlikely claim that all the bombs had fallen harmlessly on farmland (Star [Nairobi], April 6).

Inside Kenya, critical assessments of Kenya’s response to terrorist threats posed by al-Shabaab and its Kenyan allies tend to be treated as unpatriotic outbursts that identify the holder of such sentiments as potential terrorist-sympathizers. Deputy President Ruto (the government’s point-man on the Garissa issue) recently demanded that some Kenyan leaders should stop “cheering” al-Shabaab attacks inside Kenya (Capital FM [Nairobi], April 12).

Beyond the military response, focus has concentrated on the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya’s North Eastern Province. The camp, the largest refugee center in Africa with between 350,000 to 500,000 Somali residents, was set up in 1991, and its population (mainly women and children) has grown every year despite claims from many Kenyan politicians that the facility harbors terrorists. Following the Garissa attack, Deputy President Ruto demanded that the UNHCR close Dadaab in three months’ time, or Kenya would relocate the refugees itself (BBC, April 12).

Recent remarks by former deputy prime minister Musalia Mudavadi (in which he was supported by several MPs) gave some indication of the political mood regarding the continued existence of the Dadaab camp and its alleged threat to Kenyans:

The camp accommodates Somalia terrorists who disguise themselves as refugees. They use the camp as a base to collect intelligent information about Kenyan institutions and relay back to their accomplices in Somalia… The refugees stay in the country, seek assistance from us, mingle with our people freely yet they gather information on how to lay a trap on us. They hide their true colors and plan on how to kill us. They need to move out immediately (Star [Nairobi], April 6).

Kenyan officials insist that KDF operations in southern Somalia have now created safe spaces suitable for the return of the refugees (BBC, April 11). However, a UNHCR spokesman cited a tripartite treaty with Kenya and Somalia specifying that any return by refugees to Somalia must be voluntary, adding rather bluntly that “moving that number of people [in an unsystematic fashion] will not be possible” (RFI, April 12).

Big Fences Make Good Neighbors?

While spectacular attacks such as that on Garissa University make international headlines, there is also a daily war of attrition going on in the border counties of northeastern Kenya. According to Kenyan anti-terrorism police, there has been a terrorist attack every ten days (135 in total) since the KDF deployment in Somalia began in 2011. Most of these attacks, killing over 500 people in total, occurred in Kenya’s North Eastern province. (Mail & Guardian [Johannesburg], April 10). Ali Roba, governor of Mandera County, said in March that up to 90 people had died from terrorist activity in Mandera in the previous seven months alone, adding that he himself had survived six assassination attempts (Standard [Nairobi], March 22).

Most of this activity is blamed by the authorities on the infiltration of al-Shabaab terrorists across the poorly defended border. Nairobi’s solution, despite Somali objections, is to build a massive wall of concrete and fencing along the border, separating the ethnic Somali residents of Kenya’s North Eastern Province from their fellow Ogadeni clansmen in Somalia’s Kenyan-occupied Jubaland State (Standard [Nairobi], March 22), The hastily-implemented “Somalia Border Control Project” will cost an estimated $260 million. The porous border with Somalia is 680 kilometers long, but it is still unclear if the project will cover that entire distance. (Mail & Guardian [Johannesburg], April 10). Defending the wall will require an enormous and expensive permanent deployment of police or troops whose supplies will need to be trucked in despite a general absence of roads in the region.

Police Recruits

Deep corruption in the security services, especially the police, has produced a certain lethargy in Kenya’s response to terrorist activity. Unsurprisingly, the Garissa massacre is now being used to legitimize corrupt police hiring practices that were recently the subject of an unfavorable ruling by Kenya’s High Court, which still maintains a reputation for honesty and independence from the executive branch. The ruling cancelled the 2014 recruitment of 10,000 police recruits who had paid substantial bribes for a place on the police force.

Despite the ruling, the president issued a directive that the 10,000 police recruits should report for training immediately to protect the border with Somalia. This led to a flurry of contradictory statements from various government and oversight sources that pointed to a severe breakdown between the executive branch and the judiciary. The president’s directive constitutes a violation of the Kenyan constitution, an offense for which the president could be impeached. Kenyatta, however, has the support of a majority of parliament, making impeachment proceedings unlikely (Standard [Nairobi], April 12).

Amniyat on the Ropes?

Created by late al-Shabaab leader Ahmed Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr,” Amniyat is a secretive unit within al-Shabaab that acts as the organization’s intelligence unit while also providing internal security, operational planning and bodyguard services for al-Shabaab’s leader. In Godane’s hands, Amniyat was used to crush internal dissent through a string of assassinations and to orchestrate ruthless attacks on civilians both inside Somalia and beyond in AMISOM-member nations like Kenya and Uganda. Godane used Amniyat to consolidate his control of al-Shabaab by suspending the al-Shabaab Shura and making Amniyat the most powerful force within the organization while reporting directly to him. Amniyat has been particularly successful in infiltrating the Somali security forces and even the highest levels of the Somali Federal Government, enabling the group to carry out brazen attacks within Mogadishu and other cities before melting back into the population (Raxanreeb.com, October 22, 2014). Nonetheless, with massacres like Westgate and Garissa to their credit, Amniyat’s leaders have become targets for Somalia’s central government and its ally, the United States:

- In January 2014, a U.S. drone strike killed Sahal Iskudhuq, a senior Amniyat member.

- In late December 2014, a U.S. drone strike killed Abdishakur Tahlil, the new Amniyat commander, only days after he succeeded Zakariya Hersi as leader of the unit (BBC, December 31, 2014).

- Former Anmiyat leader Zakariya Ahmed Ismail Hersi defected from al-Shabaab to the government in January. The former al-Shabaab intelligence chief renounced violence at a government-sponsored news conference, but his defection may have been due to a feeling of insecurity due to tensions within the group’s leadership (Business Insider, January 28).

- In early February of this year, a U.S. drone strike in Dinsor killed Yusuf Dheeq, a senior Amniyat member, and several other al-Shabaab fighters (Dalsan Radio [Mogadishu], February 6).

- In late March, high-ranking Amniyat operative Mohamed Ali Hassan surrendered to Somali National Army forces in the Bakool region of southern Somalia (Garowe Online, March 30).

- Adan Garaar, believed to be the head of Amniyat’s external operations, was killed in a U.S. drone strike at Bardhere in mid-March. Garaar was a leading planner of the September 2013 Westgate attack in which 70 people were killed, as well as being especially active in organizing a wave of terrorist attacks and massacres in northeast Kenya’s Mandera County (Star [Nairobi], March 14; Standard [Nairobi], March 22).

Amniyat appears to have responded to these relentless attacks on its leadership by mounting ever more spectacular attacks on civilian soft-targets, especially within Kenya, where it operates with little local interference.

Conclusion

The presence of 2.5 million ethnic Somalis in Kenya’s chronically underdeveloped northeast region can no longer be ignored by Nairobi if it is to deal with the terrorist threat from al-Shabaab, which is also eager to recruit non-Somali Muslims in Kenya. President Kenyatta appears to have accepted the internal nature of the Islamist threat on April 4, when he told the nation: “Our task of countering terrorism has been made all the more difficult by the fact that the planners and financiers of this brutality are deeply embedded in our communities” (Guardian, April 5). At the same time, however, Kenya’s efforts are likely to be in vain so long as Kenya’s security forces fail to learn from or even acknowledge past mistakes in order to protect their reputation. In addition, Nairobi’s larger strategy of creating a buffer-state in Jubaland must also be regarded as a financially and diplomatically expensive failure in terms of ending the cross-border movement of terrorists and refugees.

Though the KDF is now in control of southern Somalia, the question is how long it would take after a KDF withdrawal for al-Shabaab forces to begin rebuilding their movement by retaking important ports like Kismayo. Recidivism is a common theme in al-Shabaab ideology (ethnic-Somalis are currently spread across several countries) and remarks made by the attackers at Garissa indicate the movement may have greater aspirations in northeastern Kenya than merely putting pressure on Nairobi. Kenya’s incursion into Somalia may have locked the nation into a long and costly struggle, pitting a government, which is determined to hold onto northeastern Kenya, against radical Somali Islamists who are intent on reversing the colonial division of 1925.

Note

- The number of dead ranges from 380 (a government estimate) to 5,000. The victims were members of the Degodia, an ethnic-Somali clan resident in Kenya that is part of the larger Hawiye confederation.

This article first appeared in the April 17, 2015 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

Kufra, the pre-colonial headquarters of the Libyan Sanusiya Order that led resistance to Italian, French and British imperialists, consists of a 50km by 20km basin containing a town and a half dozen oases. Sand seas on both sides of the basin force all traffic coming north from Sudan to pass through the region, giving it strategic importance. Kufra is inhabited mainly by local Tubu tribesmen and their rivals, the Zuwaya (or Zwai) Arabs that seized the region from the Teda Tubu in 1840. The two communities have clashed repeatedly since the collapse of the Qaddafi regime, requiring deployments of northern government-allied militias to restore order. In May 2014, Tubu leaders denied bringing Sudanese Tubu mercenaries north via the route to Kufra to help establish an ethnic-Tubu state in south-east Libya (al-Jazeera, May 9 2014).

Kufra, the pre-colonial headquarters of the Libyan Sanusiya Order that led resistance to Italian, French and British imperialists, consists of a 50km by 20km basin containing a town and a half dozen oases. Sand seas on both sides of the basin force all traffic coming north from Sudan to pass through the region, giving it strategic importance. Kufra is inhabited mainly by local Tubu tribesmen and their rivals, the Zuwaya (or Zwai) Arabs that seized the region from the Teda Tubu in 1840. The two communities have clashed repeatedly since the collapse of the Qaddafi regime, requiring deployments of northern government-allied militias to restore order. In May 2014, Tubu leaders denied bringing Sudanese Tubu mercenaries north via the route to Kufra to help establish an ethnic-Tubu state in south-east Libya (al-Jazeera, May 9 2014). Jabal Uwaynat: Where Three Borders Meet

Jabal Uwaynat: Where Three Borders Meet