Andrew McGregor

May 28, 2010

The ongoing destruction of Somalia by clan warfare, sectarian conflict and foreign intervention continues to dominate international headlines; yet across Somalia’s border with Ethiopia there is an ongoing conflict involving ethnic Somalis in a remote and inhospitable region that has had a negligible amount of media coverage. The decades-old struggle between the Ethiopian government and the Somalis of Ethiopia’s Somali Region (known as Haraghe Province until the administrative reforms of 1995) is one of brutal attacks and retaliations conducted out of sight of foreign media, which is banned from the region. Though it is best known as the Ogaden conflict, after the ethnic-Somali Ogadeni clan that leads the rebellion, ethnic-Somalis actually fight on both sides of the dispute.

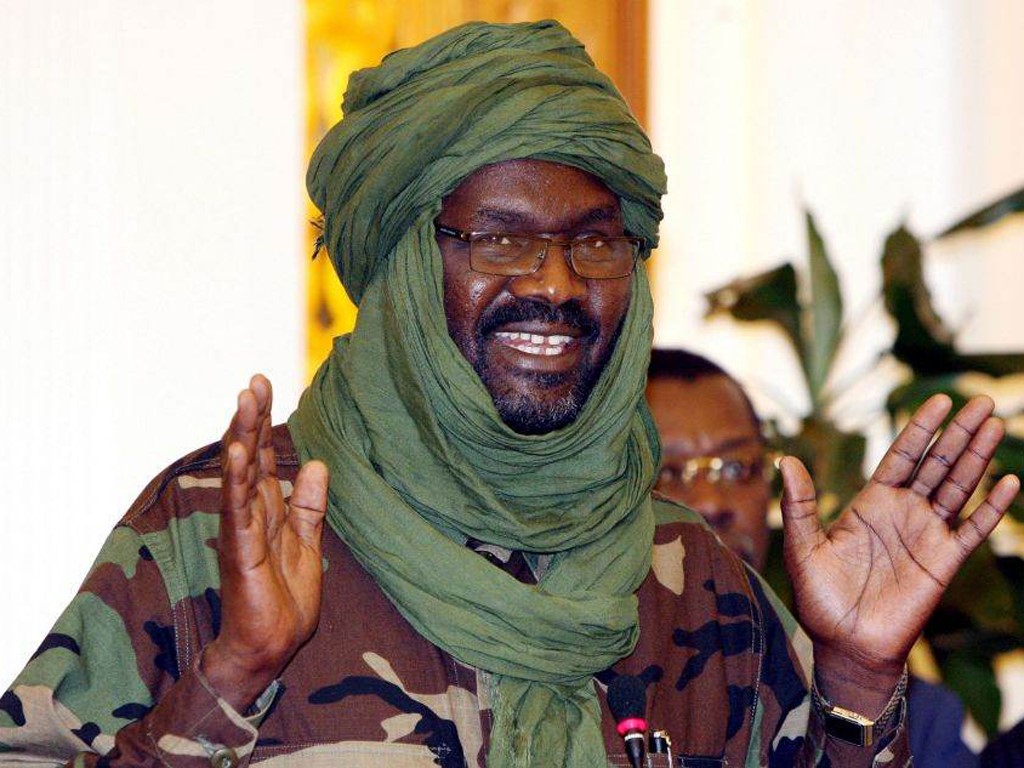

Muhammad Omar Osman

Muhammad Omar Osman

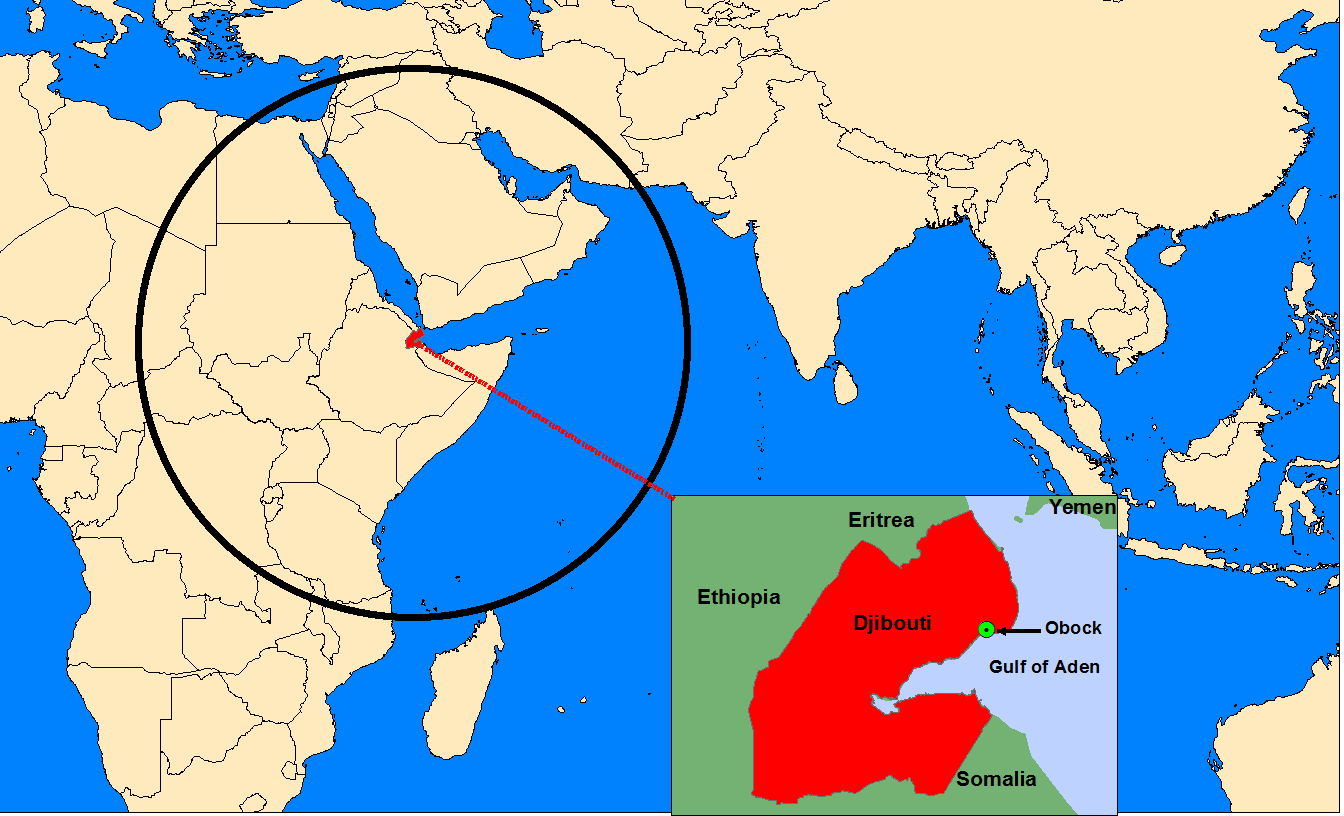

The Somali Region is the second largest of Ethiopia’s nine regions and is home to over four million people. Since its conquest by imperial Ethiopia in the nineteenth century, the region has experienced very little in the way of development or improvement. In addition, it has remained the focus of Somali nationalists who seek the creation of a “Greater Somalia” incorporating Somalia, Somaliland, Djibouti, the Somali Region of Ethiopia and the ethnic-Somali northeastern districts of Kenya. Pursuit of this goal led to the Ogaden War of 1977-78, when Somali dictator Siad Barre committed four mechanized brigades to support armed Somali separatists in the region. The conflict quickly grew out of hand, with airlifts of Soviet military equipment and 10,000 Cuban regulars tipping the scales in favor of the Marxist Derg regime (1975-1987) in Addis Ababa. Though Ethiopia eventually inflicted a devastating defeat on the Somali military, the dominant theme in its policy in the Somali Region and towards Somalia proper has been the avoidance of any repetition of such a costly and threatening episode. Since the 1991 overthrow of the Derg, Ethiopia has been ruled by the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), an umbrella group dominated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) under Prime Minister Meles Zenawi.

Even the name of Ethiopia’s Somali region is in dispute – Ethiopia’s official name is “the Somali Region,” though it also calls it the “Fifth Region”; Ogadeni clan Somalis call it “the Ogaden region” (a name rejected by the non-Ogadeni Somali clans of the region); and the pre-revolution Somali government referred to it as “Western Somalia.” The leader of the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), Admiral Muhammad Omar Osman, rejects the idea that the name “Ogaden” implies the superiority of that clan; “This is the internationally recognized name, which is shown on world maps. The Front sees no use in creating a new name for the region and then introducing it to the world anew. The former Somali government called the region Western Somalia, but few people in the region know this name.” Nonetheless, Osman says it is possible the name might still be changed “after liberation” (Asharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2009).

From Desert Tribesman to Somali Admiral

Now 70-years-old, Muhammad Omar Osman has led the ONLF since his appointment at a party congress in 1998. As a member of the Ogadeni clan, he was born within the borders of Ethiopia, but by the time he was a teenager he was attending school in the Somali capital, Mogadishu. Osman turned to a military career and pursued military studies in Egypt and the Soviet Union. As an officer of Somalia’s armed forces, Osman assumed a position within Siad Barre’s Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party, the Soviet-inspired Marxist-Leninist political wing of Barre’s military regime. Founded in 1976, the party’s leadership was dominated by military officers and Osman eventually rose to a prominent position in the party’s five-member Politburo (Bartamaha, October 12, 2009). Loyalty to the Siad Barre regime resulted in Osman’s appointment to Admiral of Somalia’s tiny navy of Soviet-built fast-attack craft. After the overthrow of the Siad Barre regime, Osman returned to his homeland, where he joined the ONLF.

Clan Militia or National Liberation Movement?

The ONLF was formed in 1984 after the collapse of the separatist Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF). The movement entered into politics in 1991 with some initial success, though the rise of the rival and more broadly-based Ethiopian-Somali Democratic League (later the Somali People’s Democratic Party) and the ONLF’s open policy of secession created strong opposition from Addis Ababa and drew support away from the ONLF, which then began a program of armed resistance to the Ethiopian state in 1994. Besides attacks on Ethiopian troops, the movement has been blamed for a series of bombings in Addis Ababa and the regional capital of Jijiga, leading the central government to designate the ONLF as a terrorist organization with alleged (but so far unsubstantiated) ties to al-Qaeda. Despite Ethiopia’s role as an American military ally, the Ethiopian regime’s characterization of the ONLF and its activities as “terrorism” has failed to bring about a U.S. or EU designation of the ONLF as a terrorist organization.

Unlike the region’s Islamic Nasrullah resistance movement of the 1960s, the ONLF is notably secular and nationalist in orientation, though there remains a subtext of tension between the Christian rulers of Ethiopia and the Muslim clans of the Ogaden region. Some reports maintain that the ONLF portrays itself as a secular movement for external consumption, but increasingly relies on an emphasis on Muslim identity and calls for jihad in its recruiting. [1] In discussions with the Arab press, Osman has not hesitated to describe the Ogaden issue as “an Arab-Islamic cause because the Ogaden people are an Arab Muslim people” (Asharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2009).

Osman calls for a “free referendum” on independence, consolidation with Somalia or a continued presence within Ethiopia for the Somali Region, though he says negotiations with the Ethiopian government are possible, so long as they take place in the presence of a neutral third party in a neutral location (Asharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2009).

Despite being personally based in Eritrea amidst widespread allegations of Eritrean military training and support for the ONLF, Osman denies any suggestion that his movement acts as a proxy in the ongoing rivalry between the leaders of Eritrea and Ethiopia; “The Ogaden Region and Eritrea were under Ethiopian occupation, and we began the war before Eritrea was liberated and also before the Eritrean-Ethiopian conflict. There is no connection between this conflict and the ONLF struggle” (Asharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2009).

Many local Somalis not belonging to the Ogaden clan (a sub-clan of the Darod) reject the ONLF as an attempt to enforce Ogadeni rule in the region. Pro-government clan militias have been formed by the government (sometimes through coercion) from members of the Isaaq, Dir and non-Ogadeni Darod clans to combat the ONLF. There were reports of heavy fighting between the ONLF and clan militias supported by government troops in late April (Jimma Times, April 30; Ogaden Online, April 24). The poorly trained and equipped clan militias typically take heavy casualties in clashes with the ONLF.

Without outside observers it is extremely difficult to assess the accuracy of battle reports from either side. For example, ONLF forces claimed a major success last year in capturing the town of Mustahil, killing 100 government soldiers while capturing another 50. A government spokesman termed the claim “absolutely false” and maintained ONLF forces were on the run (Shabelle Media Networks, March 8, 2009; Garowe Online, March 9, 2009; Somaliweyn, March 10, 2009). Only rarely do accounts bear any similarity to each other; more often one side will claim victory and the infliction of great losses on the enemy while the other side will respond with a statement saying they know nothing of any such encounter.

The ONLF frequently refers to military actions undertaken by its “Special Forces” units, such as the Dufaan commando or the Gorgor (Eagle) unit (Mareeg Online, March 7, 2009). The latter was reported to have captured the Malqaqa garrison along the road between Jijiga and Harar in mid-May, killing 94 soldiers, freeing 50 civilian detainees and seizing 192 light and heavy machine guns (Ogaden Online, May 17). As usual, these figures are impossible to verify.

Resource Exploration Intensifies the Conflict

Though the arid expanses of Ethiopia’s Somali Region offer little more economic activity than herding and other agricultural pursuits, there has been a great deal of recent speculation regarding potentially exploitable mineral deposits and oil and gas reserves. Chinese, Malaysian, Indian, Canadian and Swedish exploration companies have all become active in the region under government protection after concluding deals in Addis Ababa without local consultation. The ONLF has advised foreign exploration companies that the government does not control the region and their security guarantees are worthless (Afrol News, November 14, 2006). The movement backed up these warnings with a major attack on a Chinese-managed oil exploration site at Obala in the northern Ogaden region in April 2007 that killed 65 Ethiopian soldiers and nine Chinese oil workers. It also resulted in the short-term abduction of seven Chinese oil workers (BBC, April 14, 2007; ONLF Communiqué, April 24, 2007). The scale of the attack led to speculation that Eritrean advisors and weapons had been part of the operation. According to Osman; “If the occupation authorities exploit these resources, they will not use them to develop the region. Rather, they will use them to destroy the region and repress the people” (Asharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2009). Further warnings to foreign companies were issued last month (Shabelle Media Network, April 25).

Though the Obala operation finally gained the movement international attention, it served to justify an extremely severe crackdown on the region by Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) troops operating under the concept of collective punishment. Though outside observers were banned during the operation, refugees and local informants of human rights organizations reported summary executions of civilians, destruction of villages, torture and blockades of food and humanitarian aid. In what is clearly a “dirty war,” ONLF forces have been accused of similar human rights abuses in dealing with the civilian population.

Leadership Disputes within the ONLF

Internal disputes within the party came to a head with the January 2009 killing of the head of the ONLF’s Planning and Research Department, Dr. Muhammad Sirad Dolal. A committee of ONLF members produced a report on Muhammad Sirad Dolal’s murder in March. The report suggested that cronyism and tribal favoritism began to permeate the movement’s leadership after Muhammad Omar Osman became ONLF Chairman in 1998. Differences arose between the party leader and Muhammad Sirad Dolal after the latter opposed the Chairman’s attempt to remove Muhammad Abdi Yasin from his post as Liason for the Diaspora Community, allegedly for reasons based on tribal animosity.

Dr. Muhammad Sirad Dolal

Dr. Muhammad Sirad Dolal

In 2005 Osman claimed Dr. Dolal was preparing to defect to the Ethiopian government and issued orders that he was to be killed, orders that were subsequently ignored by fighters who did not believe the Chairman’s allegations. As the party began to split over the growing animosity between the two, Osman dismissed Dr. Dolal from the movement’s leadership. An unsuccessful assassination attempt on Dr. Dolal followed at an ONLF-dominated refugee camp in Kenya in 2008. Between November 2008 and January 2009 there were a number of clashes between the Chairman’s supporters and supporters of Dr. Dolal. Eventually Osman sent three commando teams to kill Dr. Dolal after informing them Dolal was an Ethiopian agent. After the successful conclusion of their mission on January 17, 2009 it was decided to let local government security forces take credit for the killing (Raxanreeb.com, March 23; Sudan Tribune, March 16, 2009). Dr. Dolal’s daughter has openly accused Muhammad Omar Osman and party leaders Abdirahman Mahdi Madayi, Muhammad Ismail and Adani Hiromooge of organizing his death (Raxanreeb.com, January 11). While it appears Osman’s supporters had little input to this report, it nevertheless provides background for the subsequent split in the movement.

Regardless of who was responsible, the death of Muhammad Sirad Dolal divided the ONLF. A senior movement member, Abdiwali Hussein Gas, announced the appointment of a new ONLF chairman, Salahudin Ma’ow, with the promise that the new leader would bring Osman to account for breaking up the ONLF (Jimma Times, March 3, 2009). For his part, Osman denies that any split has taken place in the movement, suggesting those who mention it are those who would like to see such a split occur (Asharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2009).

A smaller Somali movement, the United Western Somali Liberation Front (UWSLF, a local successor group to al-Itihad al-Islami) has finally capitulated to the Ethiopian government after 18 years of sporadic armed struggle (Reuters, April 9; Raxanreeb.com, May 7). Under its leader, Shaykh Ibrahim Muhammad Dheere, the UWSLF will now operate as a peaceful political movement within the terms of the Ethiopian constitution (Walta Information Center, May 6). The ONLF has criticized Ethiopian attempts to represent this event as the end of hostilities in the region (Jimma Times, May 7).

Conclusion

Amidst rumors of new challenges to his leadership from within the ONLF, Muhammad Omar Osman, the Admiral turned rebel leader, faces major difficulties in sustaining his movement’s struggle in the face of a deeply divided membership, local opposition, an unsympathetic public image, unrestrained retribution from the Ethiopian military, a lack of foreign support from any quarter other than Eritrea and general international opposition to violent movements even rumored to be linked to radical Islamists.

Note

- See Mohammed Mealin Seid, “The Role of Religion in the Ogaden Conflict,” SSRC, January 26, 2009, http://hornofafrica.ssrc.org/mealin/printable.html

This article first appeared in the May 28, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Militant Leadership Monitor

In a recent interview with the Palestinian Ma’an News Agency, Jaysh al-Islam spokesman Abu Umar al-Ansari described the ideological approach of the Salafist movement in Gaza, focusing in particular on Jaysh al-Islam’s relations with al-Qaeda, Hamas and Gaza’s Christian minority (Ma’an News Agency, May 19).

In a recent interview with the Palestinian Ma’an News Agency, Jaysh al-Islam spokesman Abu Umar al-Ansari described the ideological approach of the Salafist movement in Gaza, focusing in particular on Jaysh al-Islam’s relations with al-Qaeda, Hamas and Gaza’s Christian minority (Ma’an News Agency, May 19).