Andrew McGregor

July 1, 2011

The people of South Kordofan have become caught up in the unresolved contradiction of the post-John Garang Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), which is now leading South Sudan into independence; what happens when a national federalist political movement becomes an ethnic separatist political movement? This is the problem in several areas of Sudan outside the new borders of South Sudan, areas in which the then federalist SPLM/A recruited fighters to combat the Khartoum regime in the interests of creating a federal “New Sudan.” With South Sudan declaring full independence on July 9, a force of roughly 40,000 Nuba SPLA fighters have been abandoned in their homeland, with the SPLA declaring they are no longer part of the Southern military and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) determined to clear their presence as soon as possible.

South Kordofan is home to a number of armed groups at present, including the SPLA, the SAF, and various militias allied to both sides. Khartoum’s position is that South Kordofan is “100% Northern,” and that only the SAF would be permitted to carry arms after Southern independence is declared on July 9 (Sudan Tribune, June 16).

Khartoum’s attempt to consolidate control of South Kordofan followed its seizure of the disputed oil-producing region of Abyei in May (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, May 27). The local SPLA claim to control roughly one-third of South Kordofan (mainly in the Nuba Mountains), while the rest is controlled by the SAF’s 14th Division, much of which is locally raised and possibly reluctant to carry out operations against fellow Nuba. An SPLM press release said the SAF’s mission was to “disarm the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement component of the Joint Integrated Units in South Kordofan and to clear the area of Nuba in order to settle Arab tribes there as done in Darfur and Abyei” (Independent, June 17). [1]

The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that provided for an independence referendum in the Southern Sudan after a six-year period also called for “popular consultations” to determine the status and form of governance for South Kordofan and Blue Nile State, both of which hosted large numbers of local fighters affiliated to the SPLA during the 1983-2005 civil war. The CPA stated that the consultations could not be held until local elections were held. In Blue Nile State, the SPLM candidate, Malik Agar, won election as governor, but in South Kordofan, numerous delays held up elections until May, when the candidate of the NCP, Ahmad Haroun, was a surprise victor over the SPLM candidate. The NCP were also majority winners for the local state legislative assembly. As a result, the mostly Nuba SPLA fighters were given the choice of disarming or leaving for the South by June 1 (The CPA does not call for the complete removal of SPLA forces until July 9). Since nearly all the fighters are residents of South Kordofan, moving to South Sudan was rejected as an option. By June 5, SAF tanks, infantry and artillery began to roll into the regional capital of Kadugli in a show of force that quickly broke out into open conflict.

The Nuba

Most of the SPLA fighters remaining in South Kordofan are members of the Nuba, a collection of various indigenous tribes that took refuge in the easily defended Nuba Mountains (more a chaotic collection of hills and ravines covered by a multitude of giant boulders) and gradually adopted a common culture and identity, though the vast range of Nuba languages require the use of Sudanese Arabic as a lingua franca. Fiercely independent, they resisted Mahdist efforts to conquer them in the late 19th century and later British efforts to control the hills and their thousands of caves and other places of refuge continued into the 1920s. The development by necessity of a “warrior culture” has helped stiffen the Nuba defenses – as one British officer sent to the region noted: “Second to their interest in female society comes a love of firearms. No man among them is of account until he is the owner of a rifle of sorts, and the methods employed to gain this end would often make an Afridi border thief blush with envy.” [2]

Under the current regime, there have been extensive efforts to “Islamize” the Nuba, by force if necessary. Many Nuba are already Muslims, though there are also large communities of Christians and followers of traditional beliefs. This and growing pressure on their lands led to SPLA recruitment in the area in 1986. By 1989 local Nuba leader and SPLA Commander Yusuf Kawa led the newly formed “New Kush Division” into the hills to open a new front in the civil war. Divisions within the SPLM/A leadership left the Nuba largely on their own to combat government forces that extracted revenge on the local population through a series of offensives. The death of the charismatic Yusuf Kawa from cancer in 2001 took much of the steam out of the rebellion, and an internationally supervised ceasefire was in place by 2002.

The May Elections

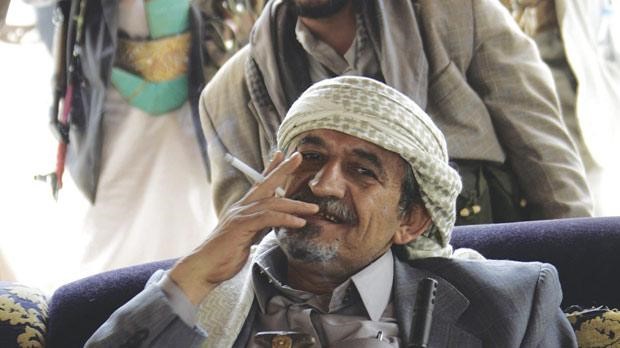

While the exact spark that began the fighting may be hard to identify, the stage for the conflict was set during the May elections for South Kordofan. SPLM candidate and veteran SPLA commander Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu lost the governor’s post to the NCP’s Ahmad Haroun, while the ruling NCP took a surprising 33 seats in the legislative assembly to the SPLM’s 21 (Sudan Tribune, May 18). Al-Hilu withdrew from the elections as the votes were counted, charging the NCP with vote-rigging. Soon after, he announced he was in high-level talks with the SPLM government of South Sudan and had received their support (Sudan Tribune, May 18).

The new governor, Ahmad Haroun, is a veteran of the largely Arab Murahileen mounted militias formed to raid Southern Sudanese tribes in the border regions during the 1980s. In the 1990s Haroun was involved in the brutal campaign to punish the Nuba of South Kordofan for supporting the SPLA, a reprisal campaign that did not differentiate between Muslim and non-Muslim and left roughly 200,000 civilians dead. By 2003 Haroun was Minister of the State for the Interior and played a major part in organizing the Arab Janjaweed militia to attack non-Arab Muslim civilians suspected of supporting the Darfur insurgency. In respect to these activities, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Haroun on multiple charges of crimes against humanity in April 2007. In response, Khartoum appointed Haroun to head an investigation into human rights abuses in Darfur.

Fighting Breaks Out

Clashes between the SAF and the SPLA are reported to have begun when government troops attempted to disarm SPLA fighters in Kadugli, the administrative center of South Kordofan. Attempts to do the same in the nearby town of Dilling appear to have led to SPLA troops opening up on the SAF, killing an SAF officer and eight soldiers (Sudan Tribune, June 9). SAF sources cited an attack on a police station in Kadugli on June 4 and a nearly simultaneous attack by SPLA forces against SAF troops in Um Dorain, 35 km southeast of Kadugli (Independent, June 17).

Nuba Fighters of the SPLA-N on the Move in South Kordofan (IRIN)

Nuba Fighters of the SPLA-N on the Move in South Kordofan (IRIN)

The Khartoum government presented the events in Kadugli as a SPLM/A attempt to overthrow the regional government in South Kordofan. According to President Omar al-Bashir: “The armed forces have aborted the plot of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) which was aiming to occupy Kadugli… and inaugurate Abdul-Aziz Al-Hilu as ruler for Sudan… What happened in South Kordofan was a betrayal operation by the SPLM. Unfortunately, there was killing, destruction and displacement. The development in South Kordofan, which has been witnessing the biggest development process in Sudan, was crippled” (Xinhua, June 22).

Presidential advisor Dr. Nafi Ali Nafi called the fighting in South Kordofan proof of a specific SPLM/A agenda in the region that involved taking control of South Kordofan either through elections or force as the first step in joining with other unnamed parties in seizing Khartoum (Sudan Vision, June 15). Dr. Nafi also said the NCP had given the SAF “a free hand” to eliminate disturbances in South Kordofan (SUNA, June 8). President Omar al-Bashir accused the SPLA in South Kordofan of “treachery,” adding: “We hope that now they understand… anyone who looks our way, we will stab his eyes” (Sudan Tribune, June 20).

Despite the looming independence of South Sudan, a form of the SPLM known as SPLM-Northern Sector (SPLM-NS) remains active in the North. The chairman of the SPLM-NS is Malik Agar, a former SPLA commander in the Blue Nile Region in the 1990s who was later elected governor of Blue Nile State in 2010. Agar became chairman of the SPLM-NS in February 2011. Despite its associations with the Southern secessionist movement, the SPLM has now become one of the largest political parties in North Sudan. However, like the SPLA fighters in Kordofan, the SPLM-NS has an uncertain future after South Sudan takes independence. An NCP spokesman has already announced that the movement would not be allowed to continue operating in its present form “because it is the party of another country” (AFP, June 18).

Governor Haroun has promised “the severest punishment” will be dealt out to al-Hilu when he is seized by SAF forces who are looking for him in the mountains south and east of Kadugli. Haroun blamed “left-wing elements” under SPLM-NS Secretary General Yasir Arman for inciting resistance to the state against the wishes of many SPLA fighters in South Kordofan who desired a peaceful resolution of existing problems (Sudan Vision, June 11).

In a June 9 interview with pan-Arab daily al-Sharq al-Awsat, al-Hilu seemed to confirm the government’s allegations by saying he was leading a battle to accomplish “fundamental change in the center.” Al-Hilu called on the Sudanese people to overthrow the Bashir regime in order to eliminate political, social, economic and religious marginalization in Sudan, policies which generate “civil wars, discrimination and instability.”

Khartoum Describes a Plot

Local residents and aid workers have reported house-to-house searches for SPLA troops and supporters conducted by Popular Defense Force (PDF) militias. Extrajudicial killings by government militias and a series of assassinations of local NCP leaders by the SPLA have also been reported (AFP, June 12). NCP cabinet minister Haj Majid Swar claimed government security forces had discovered documents in al-Hilu’s home outlining a campaign to target senior NCP figures in Kadugli and nearby Dilling before liquidating SAF forces in the area and seizing Kadugli (Sudan Vision, June 15; Sudanese Media Center, June 20). Colonel Osama Muhammad of the SAF’s 14th Division elaborated on these claims on June 18, saying seized documents showed a SPLA plot to assassinate military and political figures in South Kordofan, including Governor Ahmad Haroun. According to the Colonel, the plot was supported by the willing participation of the UN and a number of local and foreign NGOs (Sudan Tribune, June 18).

Much of the fighting has consisted of ancient SAF Antonov bombers, Mig fighter jets and ground-based artillery shelling SPLA positions in the hills surrounding Kadugli. The Antonovs are Soviet-made transports last made in 1979 that have been converted to use as bombers in the Sudanese Air Force. Due to their improvised nature and the poor quality of their munitions (primitive “barrel-bombs” were often used in Darfur), the Antonovs must fly relatively low to have any degree of accuracy in bombing runs. On June 12, a SPLM-NS spokesman claimed the group’s fighters had downed two government warplanes on June 10, including an Antonov bomber and a MiG fighter. An SAF spokesman responded by describing the claim as “completely wrong” (AFP, June 12).

The International Role – The United Nations and African Union

As part of its mandate, the Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) section of the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) has disarmed thousands of pro-government and pro-SPLA fighters since 2009 (Miraya FM, December 28, 2009). UNMIS has complained that the closing of the Kadugli Airport and restrictions on South Kordofan airspace imposed by the SAF have made it difficult to distribute much-needed humanitarian aid. On June 17, SAF aircraft dropped several bombs close to the UN compound at Kadugli. At one point, four UNMIS soldiers were detained and abused by SAF troops in Kadugli (Sudan Tribune, June 29). Egyptian peacekeepers with UNMIS in South Kordofan have also been accused of collaboration with the Khartoum regime as well as criminal activities by Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu (Sudan Tribune, June 9). By mid-June, reinforcements led by 120 Bangladeshi troops were on their way to join AMISOM forces in Kadugli, whose base had become the focus of fighting in the town as it tried to shelter displaced locals (AFP, June 17).

The African Union has created the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel (AUHIP) to mediate between North and South Sudan on issues such as the status of South Kordofan and Abyei. Former South African president Thabo Mbeki chairs AUHIP after having previously chaired the African Union Panel on Darfur (AUPD). Just as Mbeki came under criticism from Darfur rebel groups for siding with Khartoum, the former president has now come under fire in some quarters for similarly siding with Khartoum in the South Kordofan crisis. A letter to Mbeki from leading SPLM figure Edward Lino told the AUHIP chair: “All your plans are pro-Khartoum… Khartoum has long decided to ‘use you’ properly and you accepted willingly, letting our people in Abyei and the Nuba Mountains be exterminated!” (Sudan Tribune, June 19).

However, by June 30, Mbeki had managed to broker a deal calling for the SPLA fighters in South Kordofan to be either disarmed or integrated into the Northern army, with a provision that disarmament was not to be carried out by force. The effectiveness of these measures remains uncertain, as it would appear initially that neither of these options would be palatable to the Nuba SPLA forces.

Darfur’s Rebels and the Conflict in South Kordofan

The election of Ahmad Haroun as Governor of South Kordofan appears to have attracted the interest of Darfur’s rebel groups, who believe they have a score to settle with the former Janjaweed commander. In an interview from Kampala, Abu al-Gamim Imam al-Haj, a prominent member of the largely Fur Sudan Liberation Movement – Abdul Wahid (SLM-AW), announced that his movement would work with Abdul Aziz al-Hilu and the Kordofan branch of the SPLA to use any means available to bring down the Khartoum regime, including strikes, civil disobedience and military operations (Radio Dabanga, June 17).

Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), with a largely Zaghawa leadership, claimed to have used its long-range desert raiding skills to mount a June 9 attack and brief occupation of the Heglig airport in Western Kordofan, center of the North Sudan’s most productive oil field. JEM Field Commander Elnazir Osman said the raiding force had fired a number of RPGs at oil field installations, forcing a temporary shutdown (Radio Dabanja, June 11). A JEM statement said that the attack by “JEM Kordofan” was “meant to send a clear message to oil companies that use of their airports and other facilities by the Government of Sudan [and] its army and militia will not go unpunished…” (Sudan Tribune, June 14).

The speaker of the JEM Legislative Assembly, Dr. Tahir al-Faki, has called for the imposition of a no-fly zone in the Nuba Mountains to protect civilian lives. He described the fighting in South Kordofan and the “appointment” of Ahmad Haroun as the beginning of a process of ethnic cleansing similar to that experienced in Darfur: “Having orchestrated the Darfur genocide, Haroun is the right choice for the Government of Sudan to complete the unfinished job to ethnically cleanse the Nuba People and bring in Arabs to occupy their lands” (Sudan Tribune, June 21).

Khartoum has repeatedly claimed that JEM guerrillas are fighting on behalf of Mu’ammar Qaddafi in Libya, though these claims have not been confirmed (see Sudan Tribune, June 21, May 31).

Conclusion

Khartoum seems to have correctly assessed that the SPLM/A of South Sudan would be reluctant to intervene in South Kordofan so close to independence. The SPLM seems to have given little thought to the fate of its abandoned Nuba Army; if they did, it seems they were unable to come up with some other solution than the nebulous “Popular Consultations,” which, being short of any mechanism enforcing the popular will, seem simply to be code for “Return to the North.”

Khartoum has little choice but to allow the South to leave; the overwhelming vote for independence (98.83 %) has left no room for dispute. However, the regime appears to have decided to draw the line there. There will be no more “disputed territories” or regions “whose future will be decided by popular consultations.” In South Kordofan and Abyei, the North will want to consolidate control over the few productive oil fields left within its grasp.

Khartoum’s attempt to consolidate its position in South Kordofan and eliminate potential sources of opposition there have been coupled with reinvigorated attempts to strike a deal with the Darfur rebels before South Sudan becomes independent on July 9. Khartoum’s policy has always been to prevent Sudan’s multiple centers of discontent from acting in concert to depose the Nile-based Arab regime in the capital. The government faces potential opposition from the Beja tribes of east Sudan (who have already conducted a low-intensity rebellion against the regime), growing discontent in Nubia over a series of dam-building projects and possible armed opposition in the Blue Nile region. There is also sure to be dissatisfaction within the NCP’s traditional power-base over the government’s failure to prevent the oil-rich South from seceding. Under these conditions and with so many unresolved issues still outstanding between Khartoum and the SPLM, including the still unresolved fate of the Nuba SPLA, it seems unlikely that the ceasefire in South Kordofan will hold for long, adding yet another element of instability to Africa’s largest and possibly most diverse country.

Notes

1. 40,000 SPLA troops in South Kordofan, 6000 of which belonged to the Joint Integrated Units, a largely failed attempt under the CPA to integrate SAF and SPLA forces to regulate disputed border territories.

2. A.J.P., “The Hillmen of the Soudan,” Blackwood’s Magazine 1308, October 1924, p.560.

This article first appeared in the July 1, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.