Andrew McGregor

September 16, 2016

Though Nigeria’s southern Delta region has abundant oil reserves that should provide amply for the future of both the region and the nation, the Delta has become consumed by environmental degradation, unrestrained oil theft, destruction of infrastructure and a new wave of anti-government militancy complicated by ethnic friction and political rivalries.

Niger Delta Military Operations (Premium Times)

Niger Delta Military Operations (Premium Times)

Large stretches of the Delta region have little to no government presence or infrastructure of any kind. [1] For many residents, their only contact with the government occurs when troops arrive searching for militants or oil thieves. Delta residents complain routinely of being treated as militants, potential militants or supporters of the militants.

Nonetheless, government impatience with the seemingly endless instability that threatens the oil-dependent national economy boiled over at a recent African development conference in Nairobi, where Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari was quoted as saying: “The militants must dialogue with the federal government or be dealt with in the same way [as] Boko Haram. We are talking to some of their leaders. We will deal with them as we dealt with Boko Haram if they refuse to talk to us” (Naij.com [Lagos], August 30).

The threat to treat secular Delta militants in the same fashion as Boko Haram’s Islamist fighters reflects the frustration of bringing an end to one group’s operations only to see several new militant groups pop up in its place. More importantly, it is a sign that Nigeria’s federal government recognizes there will be an economic crisis unless something is done quickly. Nigeria’s budget assumes a daily production of 2.2 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil, providing 70 percent of national revenues. The actions of the Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) and other groups has lowered daily production by 700,000 bpd to 1.56 million bpd in the last few months. On September 4, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) warned that “If the current situation remains unchecked, it could lead to the crippling of the corporation and the nation’s oil and gas sector, the mainstay of the Nigerian economy” (Reuters, September 5).

The Niger Delta in Nigerian Context

The Niger Delta in Nigerian Context

An expensive war in the northeast and low international crude prices only exacerbate the problem. Buhari, already dealing with a recession, is unlikely to want to be remembered as the president who oversaw the collapse of Nigerian federalism, though this remains a danger if the government is unable to provide development programs, services, security and government salaries and pensions due to a loss of oil revenues.

The Military Approach

To help address the crisis in the Delta creeks, Operation Crocodile Smile was launched on August 29. The new military operation joins the ongoing Operation Delta Safe, a military effort launched in late June and led by the all-arms Joint Task Force (JTF) aimed at ending bunkering and other forms of crude oil theft (The Sun [Lagos] June 26).

Chief of Army Staff Lieutenant-General Tukur Buratai explained the purpose of the exercise:

Operation Crocodile Smile … is an exercise aimed at training our men on amphibious warfare because of the peculiarity of the terrain that requires special training. This exercise is also important because of the need to build the capacity of our men, which has been neglected for a very long time (Vanguard, September 8).

The Nigerian defense spokesman added that the operation was designed to provide security for Delta residents, and the region’s economic assets, while demonstrating the ability of security forces to rein in criminals and “economic saboteurs” (Vanguard [Lagos], August 29; Premium Times [Abuja], September 6).

The operation involves an estimated 3,000 Nigerian Army troops, along with air and naval elements. Most of the troops involved belong to the army’s 4th Brigade, based in Benin City, Edo State, and the 13th Brigade based in Calabar, Cross River State. Calabar is home to the Nigerian army’s amphibious training school, which is playing a large training role in the operation.

Transport and firepower for raids in the largely road-less creeks region is provided by gunboats and speedboats. For operations on firmer turf, the Nigerian army’s Armored Corps has contributed two main battle tanks (likely the British-built Vickers MBT or Russian-built T-55s or T-72s), two South African-built MRAP (Mine-Resistant, Ambush Protected) armored personnel carriers and three British-built FV101 Scorpion reconnaissance vehicles.

On September 10, Chief of Army Staff Tukur Buratai announced the creation of a new brigade, the 61st, to be based in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State with the aim of increasing security in the Delta region (TVC News [Lagos], September 10). According to Buratai, the army plans to have 10,000 troops operating in the Delta by 2017.

Objections to Operation Crocodile Smile

Operation Crocodile Smile has been far from universally welcomed. Colonel Abubakr Umar (Ret.), the influential former military governor of Kaduna State, issued a statement on August 30 claiming that the Niger Delta militants could not be called terrorists “in the real sense of the word,” adding that military operations in the densely populated Delta faced major challenges, including difficult terrain, the possibility of setting the oil-polluted creeks on fire with explosives, international opposition, and the danger of inadvertently shutting down oil and gas operations in the entire region (Punch [Lagos], August 30).

Ijaw representatives claim the military operations target their community unjustly and complain the military approach comes at a time when a negotiated settlement looked promising. At the same time, JTF personnel have been accused of demolishing homes, beating up residents and stealing speedboats in Ijaw communities.

The commander of Operation Delta Safe, Rear Admiral Joseph Okojie, however, has insisted the Nigerian army is “people-friendly” and has prioritized the protection of lives and property (This Day [Lagos], September 9). [2]

The “people-friendly” aspect of Operation Crocodile Smile involves school-building, infrastructure rehabilitation and the provision of health services in areas that have seen little improvement from the riches drawn from their region. For General Buratai, the inclusion of these services trumps accusations of human-rights abuses during the offensive. “How can people grumble when we have medical outreach in their communities, there is no way they can grumble … we are supporting the communities, they are happy,” he said (Vanguard [Lagos], September 6).

Active Militant Groups in the Niger Delta

The lack of unity or any common approach amongst the Delta militants is a major impediment to reaching a negotiated settlement. Federal government negotiations with elders and stakeholders in the Delta region reached an impasse in August when Delta representatives demanded a payment of NGN 8 billion ($25.37 million) to continue, a demand President Buhari rejected (Sahara Reporters, August 6). The impasse left dialogue in the hands of a MEND-supported negotiating team, Aaron2, operating as part of the Niger Delta Dialogue Contact Group (NDDCG) led by Foreign Minister Henry Odein Ajumogobia, formerly the minister of state petroleum resources, and King Alfred Diete-Spiff. [3] Many smaller Delta-based ethnic groups claim the NDDCG represents only Ijaw interests.

As seen from the list below – which due to the sheer number of factions active in the region does not pretend to be comprehensive – some groups are at odds with each other as much as with the federal government:

Aggrieved Youth Movement (AYM): This group is composed mainly of amnestied militants based in Rivers State. AYM claims to be non-violent and against the destruction of oil and gas installations. The group has warned other militant groups to stay out of Rivers State (Daily Post [Lagos], September 5).

Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB): A secessionist group that has given its support to the NDA. Its leader is Nnamdi Kanu, the self-styled “president” of Biafra, is currently imprisoned.

Joint Niger Delta Liberation Force (JNDLF): Only several months old, this group claims to be affiliated with the NDA and has threatened to use missiles in its possession to shoot down military helicopters (International Business Times, June 2). In late June, members of the group told media sources they had been approached by senior Nigerian military officers interested in enlisting the group’s support for a coup against President Buhari, though the claim is likely baseless (Vanguard [Lagos], June 24).

Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB): A secessionist group led by Ralph Uwazuruike. Allegedly non-violent (though this is disputed by the government), the group has pledged “total allegiance” to the NDA (The Trent Online [Lagos], August 11).

Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND): This group is largely inactive since most of its leaders are imprisoned or have accepted the 2009 amnesty. MEND still seeks a role in Delta-related negotiations and has warned it will not talk to the government if Ijaw leader Chief Edwin Clark is appointed to speak for the Delta (Pulse.ng, August 22). MEND has threatened to take up arms against the NDA if it does not pursue dialogue with the government and recently declared “its full support for the ongoing military presence in the Niger Delta region” through its spokesman Jomo Gbomo (a pseudonym used by a number of Delta militants) (Pulse.ng, August 21).

Niger Delta Avengers (NDA): The NDA’s declared aim is to reduce Nigerian oil output to zero with a minimum of casualties. The NDA declared a unilateral ceasefire on August 29 and has expressed its interest in holding talks with the government, though it accused Buhari of organizing “a pre-determined genocide” in the Delta and warned the army that “no amount of troop surge and simulation exercises will make you win the oil war” (NigerDeltaAvengers.org, August 29). Ijaw Youth Council president Udengs Eradiri is alleged to be the NDA’s chief spokesman, ‘Brigadier General’ Murdoch Agbinobo (Pulse.ng, August 20).

New Niger Delta Emancipation Front (NNDEF): A new group whose only known leader is Lucky Humphrey, its so-called “director of public enlightenment and awareness.” The NNDEF rejects the “narrow interests” pursued by the militants and applauds Buhari’s military intervention to root out the militant groups (This Day [Lagos], September 8).

Niger Delta Greenland Justice Mandate (NDGJM): A Delta State group dominated by members of the Urhobo ethnic group, the largest in the state. Commanded by Aldo Agbalaja, the group believes President Buhari is committing “genocide” in the Niger Delta and followed a strike on a major trunk delivery line in Delta State by warning employees at a number of energy facilities to abandon their plants “because what is coming to those facilities [is] beyond what anybody has seen before” (Sahara Reporters, August 30). The NDGJM responded to the launch of Operation Crocodile Smile by bombing the Ogor-Oteri pipeline. The group opposes what it sees as one-sided government negotiations with the region’s much larger Ijaw ethnic group and its leader, 84-year-old Chief Edwin Clark, who they see as only “the leader of the Ijaw nation.” (Vanguard [Lagos], August 10). The group would prefer to join in talks led by King Alfred Diete-Spiff (Pulse.ng, August 23).

Niger Delta Red Squad (RDRS): Operates in Imo State, active for three months. Spokesman is “General” Don Wannie (or Waney) (Naij.com [Lagos], September 1). The Red Squad has attacked pipelines operated by the Nigeria Agip Oil Company (a Nigerian-Italian joint venture), citing its alleged neglect of local communities. The group has threatened to behead any security agents it manages to seize (Naij.com [Lagos], September 1).

Niger Delta Searchlight: Commanded by “General” Igbede N Igbede, this group rejects negotiations with the government and claims it will continue a bombing campaign until oil companies abandon the Delta region (Daily Post [Lagos], August 30).

Otugas Fire Force (OFF): The OFF is commanded by “General” Gabriel Ogbudge, who was arrested by the Nigerian Army’s 4th Brigade on September 6 during a raid in Edo State. Ogbudge is the primary suspect in the August 26 demolition of a major Nigerian Petroleum Development Company/Shoreline trunk delivery line. On August 31, Ogbudge declared the launch of Operation Crocodile Tears, the group’s response to the government’s Operation Crocodile Smile. The OFF was alleged to be planning an attack on the Utorogu gas plant (Punch [Lagos], September 7; Naij.com, September 7).

Reformed Egbesu Boys of Niger Delta: The group rejects any dialogue led by the NDDCG and aims for a total shutdown in oil production in the Delta (Vanguard, July 22). Egbesu is the Ijaw god of warfare and the group is as much a religious cult as a militant formation. The group’s leaders are “General” Tony Alagbakereowei and Commander Ebi Abakoromor.

Reformed Niger Delta Avengers (RNDA): The alleged leader of this NDA offshoot is one Jude Kekyll, whom the NDA denies was ever a member of their group (Vanguard [Lagos], August 6). The NDA maintains that the RNDA is a creation of Buhari’s government and does not represent a split in the movement. Meanwhile, the RNDA says it split from the NDA to pursue dialogue with the government and to avoid further environmental destruction of the Delta region (Vanguard [Lagos], August 6).

The Mysterious Cynthia Whyte

A sensational RNDA statement issued in August by “spokesperson” Cynthia Whyte identified a number of prominent Nigerians as sponsors of the NDA, including former president Goodluck Jonathan (which it accused of being the “grand patron” of the NDA), governors Nyesom Wike (Rivers State) and Seriaki Dickson (Bayelsa State), former Akwa Ibom State Senator Godswill Akpabio and fugitive militant leader Government Ekpemupolo (aka Tompolo) (Sahara Reporters, August 6; Sahara Reporters, August 16).

Niger Delta Red Squad (NAIJ.com)

Niger Delta Red Squad (NAIJ.com)

Former president Jonathan responded to the accusations by noting that Cynthia Whyte was a name used for an earlier spokesperson for the Joint Revolutionary Council (an umbrella group for Delta militants) beginning in 2005 and suggested that, like MEND at the height of its power, the RNDA was intent on assassinating him (Punch, August 8). However, an individual using the official Cynthia Whyte email address claimed that the recent RNDA statements delivered under that name were those of an imposter. The “real” Cynthia Whyte blamed the RNDA fraud on “retired militant leaders from Bayelsa and Delta State who have made lots of money in past time through character blackmail and sabotage” (The Trent Online [Lagos], August 11).

There are suspicions that Cynthia Whyte is a pseudonym lately appropriated by the imprisoned Charles Okah. Charles is the brother of MEND leader Henry Okah, currently serving a sentence in South Africa (Elombah.com [London], August 21). The NDA believes the name Cynthia Whyte may have been resurrected by George Kerley, a Rivers State social activist and supporter of the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP), though they claim the content (described as “delusional”) originated with Victor Ebikabowei-Ben (a.k.a. Boyloaf), an amnestied ex-MEND leader (Today [Lagos], August 8; Nigerian Nation, August 8).

Though the list of alleged sponsors is largely unverifiable and probably inflated (if it has any basis in reality at all), it has helped fuel an incendiary Nigerian political environment where suspicion of treachery is the order of the day.

Deepening the Divide

Negotiations imply recognition and, if successful, tend to lead to some form of legitimacy for insurgent groups. This was the case with the last generation of Niger Delta militants, many of whom now receive generous government payments to keep in line.

Negotiating with the NDA and its allies and rivals may encourage new movements to seek eventual status and wealth by issuing statements and taking to the creeks to blow up a few pipelines, creating a perpetual and debilitating cycle of rebellion-negotiation-cash settlement.

However, folding the conflict into Nigeria’s broader “war on terrorism” is unlikely to produce anything other than short-term results, while encouraging the return of southern separatism and deepening Nigeria’s north-south divide.

Notes

[1] The Niger Delta consists of the following states: Ondo, Edo, Delta, Bayelsa, Rivers, Imo, Abia, Akwa Ibom and Cross River.

[2] Operation Delta Safe replaced Operation Pulo Shield in June 2016.

[3] Diete-Spiff’s title indicates he is one of Nigeria’s traditional rulers – in this case the Amanyanabo (King) of Twon-Brass, a community in southern Bayelsa State.

This article first appeared in the September 16, 2016 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

Mozambican Troops Inspect Terrorist Damage in Cabo Delgado (PetroleumEconomist)

Mozambican Troops Inspect Terrorist Damage in Cabo Delgado (PetroleumEconomist) Russian Cargo Plane Unloads Military Supplies at Nacala International Airport, September 26, 2019 (ClubofMozambique)

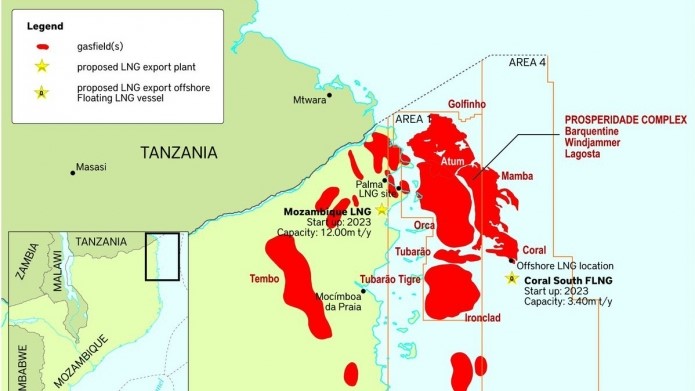

Russian Cargo Plane Unloads Military Supplies at Nacala International Airport, September 26, 2019 (ClubofMozambique) LNG Fields in Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin (BankTrack)

LNG Fields in Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin (BankTrack)