Dr. Andrew McGregor, CIIA

Shout Monthly, Toronto, August 2002

New developments in the ancient Berber-Arab conflict in Algeria have seen disaffected Arabs making common cause with the Berber minority against the Algerian government. While the Berbers have enjoyed important victories, their struggle with the Algerian government continues. Meanwhile, the Berbers – like most of the Islamic world, non-Arabs who do not necessarily share the goals of Arab Islamists – face violent opposition from the Islamic insurgents. Dr. Andrew McGregor explores recent events.

Wild street celebrations in the towns of the Kabyle mountains of Algeria welcomed the pardon and release of dozens of Berber activists from Algerian prisons on August 5. President ‘Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s concession to Berber demands for a presidential amnesty gave the appearance that the struggle between the ethnic Berber minority and the Algerian government and security forces has taken a turn in favour of the Berbers. This struggle is often depicted as part of the old rivalry between Arabs and native Berbers in northern Africa, but last summer the Berber opposition became dangerous to the government when Berber protests began to pull disaffected Algerian Arabs in behind them. Berber militants have demonstrated an ability to embarrass le Pouvoir, the cabal of business leaders and generals that run Algeria behind a democratic façade. The mobilized Berber opposition is especially disturbing at a time when the government is seeking to privatize Algeria’s corruption-ridden oil industry while promoting supposed democratic reforms.

Protesters in Algiers Wave a Berber Flag (Asharq al-Awsat)

Protesters in Algiers Wave a Berber Flag (Asharq al-Awsat)

As the indigenous people of North Africa, once occupying a swath of territory stretching from the Canary Islands to the Nile Valley, the Berbers endured Carthaginian and Roman rule before Muslim Arabs began to spread west in the late seventh century, eventually overpowering the native culture. The struggle between Arabs and Berbers for North Africa became part of several great Arabic-language poetic epics still told in north African coffee-shops today. Since then, the Berbers have declined in numbers and territory, though large numbers may still be found in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco (40% of the total population) as well as the mountains of Algerian Kabylia, where their 7 million people make up roughly 25% of the national population. Other groups are found in Tunisia (35% of the population), Libya, Mali, Niger, Mauritania and Egypt.

Today, in the midst of a Berber cultural revival, many Kabyle Berber leaders represent the Arabs as the latest in a series of colonizers (There are smaller groups of Algerian Berbers in the Aures mountains and the Ouarseni Massif, but the Kabylians are the most politically active). It is a mistake to regard Berbers as an excluded minority, however. Berbers can be found in the highest levels of Algerian military, political, business and intellectual circles.

The Berbers have always been difficult subjects when ruled by other peoples. Roman Christianity and Arab Islam alike were faced with a Berber affinity for heretical movements. After the Arab conquest the Berbers learned to use Islamic identities and institutions to reassert control over their communities, eventually building three great empires in North Africa and Spain between the 11th and 15th centuries; the Almoravids, the Almohads and the Maranids. Berbers bristled at Arab airs of superiority due to their intimate connection to Islam’s homeland. In response several hadith-s (traditions) were fabricated which described the conversion of the Berbers by the Prophet Muhammad himself well before the Arab conquest. The Moroccan Bargawatiyya movement translated the Koran into Berber in the 10th century, but Sunni Muslim reformists destroyed their kingdom and burnt the offensive Berber Koran.

The Berbers have always been difficult subjects when ruled by other peoples. Roman Christianity and Arab Islam alike were faced with a Berber affinity for heretical movements. After the Arab conquest the Berbers learned to use Islamic identities and institutions to reassert control over their communities, eventually building three great empires in North Africa and Spain between the 11th and 15th centuries; the Almoravids, the Almohads and the Maranids. Berbers bristled at Arab airs of superiority due to their intimate connection to Islam’s homeland. In response several hadith-s (traditions) were fabricated which described the conversion of the Berbers by the Prophet Muhammad himself well before the Arab conquest. The Moroccan Bargawatiyya movement translated the Koran into Berber in the 10th century, but Sunni Muslim reformists destroyed their kingdom and burnt the offensive Berber Koran.

Horace Vernet Painting of the First French Mass in Kabylia, 1837

Horace Vernet Painting of the First French Mass in Kabylia, 1837

The French, who finished their conquest of Kabylia in 1857, attempted to divide the Berbers from their Arab neighbours. The use of Berber customary law (qanun) rather than Islamic shari’a law was approved for Kabylia. The French also attempted to ‘re-convert’ the Kabyle Berbers to Christianity in an attempt to gain colonial allies in Algeria. While the French produced endless studies ‘proving’ a Christian legacy in Kabylia, there is little evidence that Christianity ever spread beyond a small number of culturally assimilated coastal Berbers in the later days of the Roman Empire. Though Berber conversion to Islam was widespread, their interpretation of Islamic law has always been tempered by the maintenance of pre-Islamic custom. Women are particularly important in the preservation of ancient customs and have been in the forefront of recent demonstrations.

French attempts to split Arabs from Berbers were ultimately a failure. During the struggle for Algerian independence, the Berbers stood solidly behind the revolutionary FLN (Front de Libération Nationale), providing much of the movement’s internal leadership. The post-independence government, mostly composed of returned Arab political exiles, soon found itself fighting armed Kabyle groups after Ben Bella declared Algeria an Arab state in 1962. Kabylian Berbers had a high literacy rate in French, with Arabic often a third language at best. Post-independence Arabization policies marginalized many Berbers accustomed to privileged access to government positions in the previously French-speaking government. The confusion over language and the wretched state of Algerian schools has led some Kabyle Berbers to describe their people, with bitter humour, as “trilingual illiterates.”

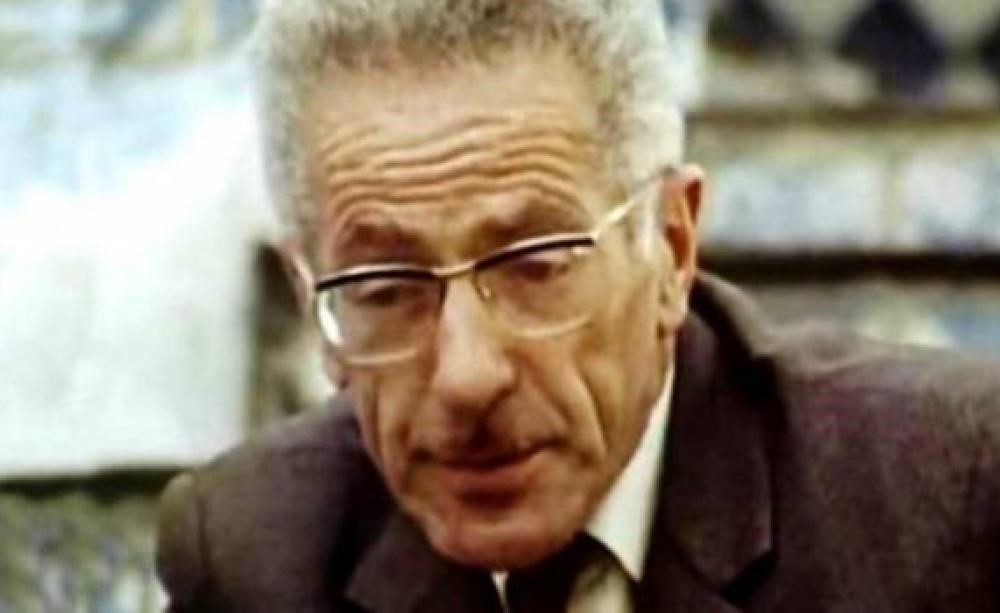

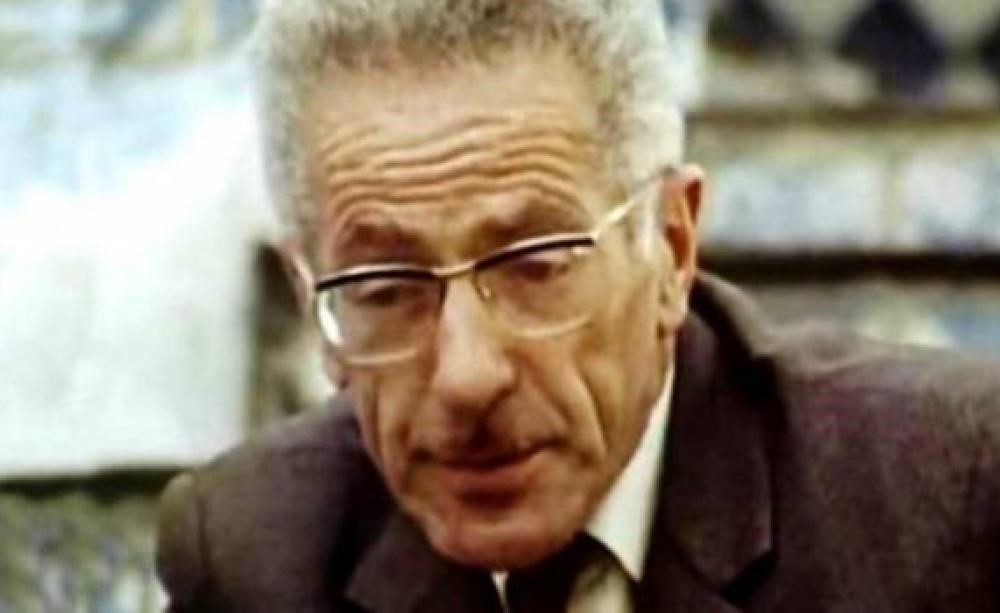

Mouloud Mammeri, 1917-1989 (Le Matin d’Algerie)

Mouloud Mammeri, 1917-1989 (Le Matin d’Algerie)

The Berber language, which now flourishes as much in Paris as in the Kabyles, is at the heart of Berber/Arab tensions. The latest round of confrontation began in 1980 when Professor Mouloud Mammeri attempted to give a lecture on ancient Berber poetry. The Algerian government showed its insecurity by canceling the lecture, leading to widespread demonstrations. Then-president Chadli Benjedid responded by declaring: “We are Arabs whether we like it or not. We belong to the Arab-Islamic civilization and there is no other identity for the Algerian citizen.” Since independence, both Berber language and culture had been dying a natural and almost unnoticed death, but a combination of forced Arabization and repression sparked a Berber renewal. According to the late Berber poet, Kateb Yacine, “They want to depict us as a minority within an Arab people, when in fact it is the Arabs who are a minute minority within us, but they dominate us through religion…”. This has become a common refrain among Berber militants, who like to remind Algeria’s Arabs that most of them are part of an Arabized Berber majority.

A major victory for the Berbers was achieved in March, when the President reversed the long-held Arabization policy to make the modern Berber language, Tamazight, a national language, declaring that ‘When we speak about Tamazight, we mean the identity of the entire Algerian people.’ A modified Latin script is now used to write Tamazight. The ancient Libyans, Berber contemporaries of the Ancient Egyptians, had used a phonetic script to transcribe their language. Preserved in slightly modified form in the Tifinagh characters used by the Saharan Tuareg, this script is now being promoted as an authentic means of recording Tamazight. It is but one example of today’s Berbers reaching to the past for forms of expression and identity. The ongoing publication in France of the Encyclopédie Bérbére is another vital development in creating a Berber cultural base. A new Berber-language translation of the Koran is also in publication.

At the forefront of Berber resistance is the Mouvement Cultural Bérbére (MCB), a group that found itself in the 1990s fighting not only government Arabization, but also attacks from radical Islamists who find fault with Berber (and most Algerian Arab) forms of Islamic worship. The Front Islamique du Salut (FIS) called for the total Arabization and Islamization of the Kabylians, and introduced the pattern of brutal murders and rural massacres that have characterized the rest of the Algerian civil war. Berber-language singers were special targets of FIS assassination squads, sometimes having their throats cut after being killed in order to make the point. As if to rub salt into an open wound, the Algerian government passed a law enforcing the use of Arabic only days after the assassination of the highly popular Berber singer Lounes Matoub in 1998. In Algeria, as in Morocco, government authorities refused to register Berber names for newborns, and legal proceedings are conducted entirely in Arabic.

(al-Jazeera)

(al-Jazeera)

Faced with government intolerance, the Kabyle Berbers must also cope with Islamists who regard them as secularists or even heretics. While the FIS has come to terms with the government, the violence has been sustained by the activities of the Groupe Islamique Armée (GIA) and the Groupe Salafiste pour la Predication et le Combat (GSPC). Both groups have prominent places on the US State Department’s list of terrorist organizations, and are linked to al-Qa’idah. Recently the government (with American backing) has finally scored major victories against both groups, raising hopes of a so-far elusive military solution to the Islamist insurrection. The government’s credibility, however, is threatened by renewed accusations of involvement in civilian massacres ultimately blamed on the Islamists. So long as the Algerian general staff remain the power behind the civilian government there is unlikely to be any investigation or resolution of these claims. In the meantime, the political violence continues, claiming 150 lives last month alone.

The Algerian Berbers are represented by two political parties, the Front des Forces Socialistes (FFS), and the smaller Rassemblement pour la Culture et la Démocratie (RCD). The RCD joined Bouteflika’s government, but has suffered in reputation as a result. Berber political activity has lately been moving away from the largely discredited political parties to the local community councils (jama’a), the traditional method of self-governance in the Kabyles. Many feel that the amnesty for Berber activists was part of an effort to avoid a Berber boycott of local elections in October. A militant-led campaign for ‘zero-balloting’ in Kabyle resulted in only a 2% turnout in parliamentary elections earlier this year. The official turnout nation-wide was set at 47%, a figure many Algerians claim is far too high. Though the opposition parties that were expected to do so well in the elections barely registered in the final tally, the results were characterized by the US State Department as ‘progress in Algeria for greater democracy’.

President Bouteflika has had little success in dealing with a morbid economy, housing shortages, severe inequities in the distribution of Algeria’s oil wealth, continuing Islamist violence and an unemployment rate of over 30% (higher in Kabylia). For Bouteflika, last summer’s Berber-generated unrest provided a convenient scapegoat for his own failures; according to the president, the unrest came just as Algeria “was about to regain its real place on the national stage, rebuild and launch an economic revival programme.” Bouteflika has also relied on the well-worn suggestion of ‘external sources’ behind the unrest. More than 60% of Algeria’s population is now under 30 years of age, and prospects are increasingly bleak. Last summer young Arab demonstrators shouted “Nous sommes tous des Kabyles!” in what the government must have found a bizarre challenge to official policy.

Unlike their Tuareg cousins to the south, who have engaged in separatist revolts in Mali and Niger, the Berbers of Kabyle are not engaged in a separatist movement. No one seriously believes that the mountains can sustain an independent country. The Berbers are engaged in a cultural and linguistic struggle based on a strong tradition of independence within a greater state. The World Amazigh Congress has concluded that:

The Algerian state cannot continue suppressing the country’s age-old language and culture. It must be the state of everyone and not only that of the citizens of the Muslim faith or Arabic speakers. It must become the state of all Algerians without discrimination on the basis of language or faith. For this reason, it must inject in the country’s constitution political, linguistic and religious pluralism.

Similar demands were made in a “Berber Manifesto” released by Moroccan Berber activists two years ago.

Algeria’s continuing instability delays the resumption of much needed foreign investment as the Algerian government lurches from crisis to crisis. For now, international reaction is mixed; Libya has expressed grave concerns about the prospect of destabilization in the Maghrab as a result of Berber/Arab conflict, France has been loudly rebuked by the Algerian government for interference after complaining of gendarmarie tactics, and Morocco, with its large Berber minority, continues to watch developments carefully. Berber demands for the removal of the heavy-handed Algerian gendarmarie from the Kabyles and more equitable distribution of energy-sector revenues continue to be sore-points. Aware of their millennia-old presence in North Africa, the Algerian Berbers appear ready to resist assimilation and to preserve an independent African and Muslim identity despite the opposition of national leaders and Islamists alike.