Andrew McGregor

Terrorist Research & Analysis Consortium

July 17, 2016

Islamist resistance to the efforts of anti-extremist government troops and militia allies to expel the radicals from the Libyan city of Benghazi has entered a crucial stage in which suicide bombers and desperate gunmen engaged in urban warfare imperil the lives of troops and civilians alike. In the midst of this conflict, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has attempted to intervene on the side of the Islamists by an unusual resort to historical anti-colonial rhetoric to rally support for the besieged fighters.

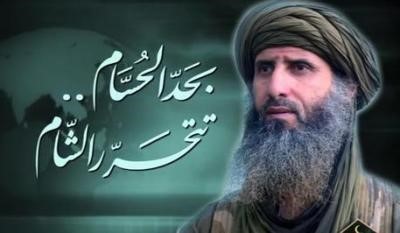

A Message from Abu Ubaydah Yusuf al-Anabi

A Message from Abu Ubaydah Yusuf al-Anabi

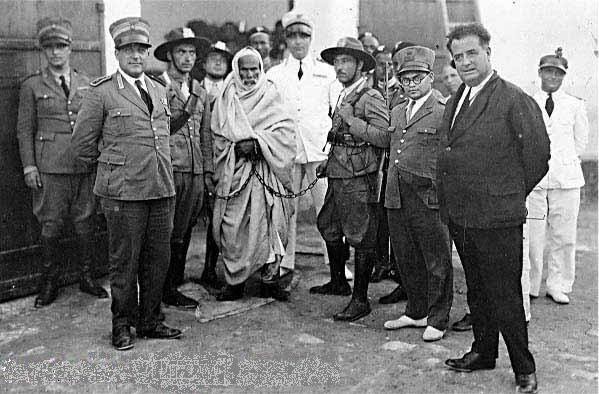

Abu Ubaydah Yusuf al-Anabi, head of AQIM’s Council of Notables and AQIM’s second-in-command, posted an audio message on June 27 urging “the descendants of Omar al-Mukhtar” to rush to Benghazi to relieve the Islamic extremists trapped there by Libyan National Army (LNA) forces and allied militias. Abu Ubaydah called on Libyans to join the fight against the LNA and “French forces” said to be assisting the LNA campaign.[1]

The Situation in Benghazi

Most of the Islamist forces in Benghazi have joined together in the Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries since June 2014. Along with Ansar al-Shari’a, the council includes the February 17 Martyrs Brigade, the Rafallah Sahati Brigade and the Libya Shield 1 militia. The Islamic State organization is also active in the remaining areas of Benghazi still held by Islamist radicals.

AQIM has never established a real presence in coastal Libya, though some members appear to have established bases in Libya’s remote south-west, intended more as refuges and jumping-off points for operations in Algeria and the Sahelian regions of Niger and Mali rather than Libya. Instead, AQIM formed ties with Ansar al-Shari’a, an al-Qaeda-inspired Islamist militant group formed in the eastern cities of Derna and Benghazi during the 2011 revolution. Leadership difficulties and military pressure in the east led some Ansar members to abandon the loosely-formed group in favor of the more focused Islamic State group centered on Sirte. AQIM tends to regard Libya’s Islamic State as a rival rather than a partner, an observation seemingly confirmed by Abu Ubaydah’s failure to use his message to call for support for the Islamic State extremists currently besieged in Sirte in the same way he called for support for the Islamist militants in Benghazi.

LNA Operations in Benghazi, July 12, 2016 (Libyan Express)

LNA Operations in Benghazi, July 12, 2016 (Libyan Express)

AQIM’s leader Abd al-Malik Droukdel (a.k.a. Abu Mu’sab Abd al-Wadud) attempted to co-opt the Libyan Revolution from afar when he claimed in 2011 that the revolution was nothing more than a new phase of the Salafist-Jihadi struggle against Arab tyrants, an assertion made once more by Abu Ubaydah in 2013.[2]

Ansar al-Shari’a has battled General Khalifa Belqasim Haftar’s “Operation Dignity” forces (the so-called Libyan National Army [LNA] and its allies) for control of Benghazi since May 2014. At the time of writing, the area controlled by Ansar al-Shari’a and other Islamist groups has been reduced to roughly five square kilometers near the port area.

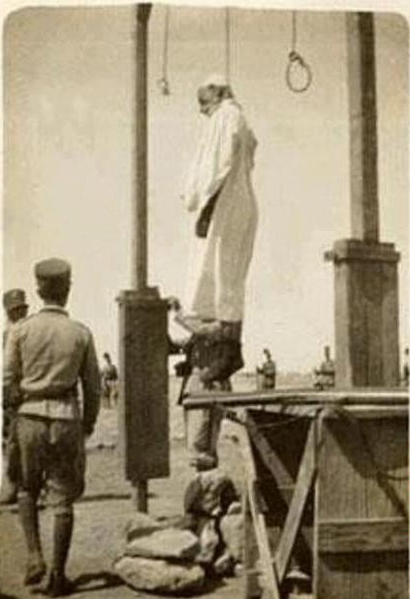

Who is Omar al-Mukhtar?

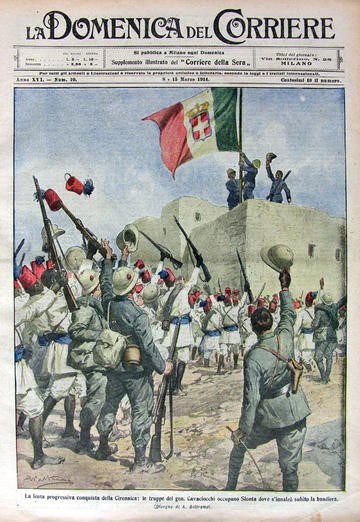

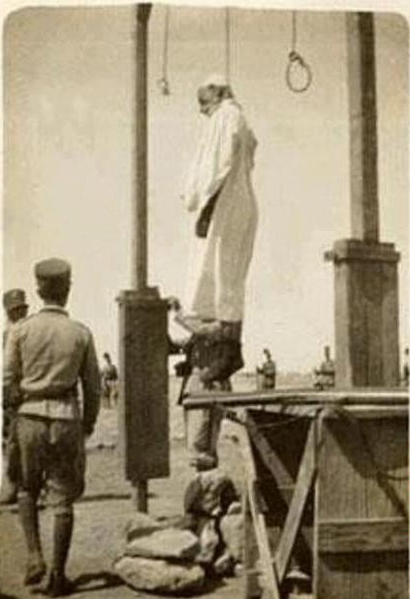

Libya’s most prominent national hero is without a doubt the Islamic scholar turned independence fighter Sidi Omar al-Mukhtar. Well versed in tactics learned opposing the Italian invasion of Libya in 1911 and during Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif al-Sanusi’s failed invasion of British-occupied Egypt during World War One, al-Mukhtar began an eight-year revolt against Italian rule in 1923 using the slogan “We will win or die!” Shortly after the wounded guerrilla leader was captured in 1931, he was hung by Italian authorities in front of a crowd of 20,000 Libyans as a demonstration of Italian resolve and ruthlessness. The resistance collapsed soon afterwards, with some 50% of Libya’s population either forced into exile or dead from starvation, exposure and battle wounds.

The Execution of Omar al-Mukhtar

The Execution of Omar al-Mukhtar

Abu Ubaydah’s invocation of Omar al-Mukhtar was not unprecedented; during the 2011 revolution al-Qaeda spokesman Abu Yahya al-Libi urged Libyans to follow the example of al-Mukhtar, “the Shaykh of the Martyrs” while claiming al-Qaeda had inspired the revolution by shattering “the barrier of fear” that preserved Muslim regimes that ruled without sole reliance on Shari’a.[3]

Al-Mukhtar’s memory was suppressed during post-WWII Sanusi rule but was enthusiastically revived by Colonel Mu’ammar al-Qaddafi after the 1969 officers’ coup as a means of giving his regime and its anti-Western policies legitimacy by drawing on Libyans’ shared experience of resistance to colonialism. Qaddafi’s first post-coup speech was given in front of al-Mukhtar’s Benghazi tomb, and soon the guerrilla leader’s image was everywhere, including on Libya’s currency. In 1981 Qaddafi financed a big-budget film biography with Anthony Quinn playing al-Mukhtar and a grim-faced Oliver Reed as his deadly enemy, Italy’s Marshal Rodolfo Graziani.

Qaddafi gradually developed a highly individualistic amalgam of Islam, socialism and anti-colonialism that, to his disappointment, failed to gain traction outside of Libya, where it became the dominant political ideology only due to the weight of the state and its enforcement agencies. Qaddafi, however, continued to claim Omar al-Mukhtar as his prime inspiration.

Al-Qaeda and Anti-Colonialism

Due to its close links to nationalism, anti-colonialism has typically been treated carefully by al-Qaeda, whose goal is the creation of a pan-Islamic Arab-led Sunni caliphate rather than the perpetuation of Muslim-majority nations whose boundaries were defined by colonial powers. Recalling the examples of earlier Islamic anti-colonial movements presents al-Qaeda’s takfiri Salafists with an undesirable minefield of ideological dangers and contradictions. To cite only a few examples; Imam Shamyl’s mid-19th century jihad in the North Caucasus was entirely Sufi-based (Sufism being rejected in its entirety by modern Salafi-Jihadists), Sufi Ahmad al-Mahdi’s 19th century jihad in Sudan was meant to overthrow rule by the Ottoman Caliph and his Egyptian Viceroy rather than a European power, while Libya’s own anti-colonial Sanusi movement evolved by the end of World War II into a British-allied monarchy of the type rejected by jihadists throughout the Middle East. Al-Qaeda’s ability to find ideological, ethnic or religious failings in every Islamic movement but its own often strangles its ability to communicate its message; when it does relax its ideological firewalls enough to make historical reference to earlier Muslim leaders outside their usual pantheon it often sounds insincere, even desperate. As might be expected, the vital role played by Western-educated anti-colonial Muslim modernists in establishing today’s post-colonial nation-states is beyond al-Qaeda’s religious frame of reference and, beyond condemnation, remains an unmentionable topic in their public statements.

The most notable exception to this approach is in AQIM’s home turf of Algeria, where the al-Qaeda affiliate has always identified its main enemy as former colonial power France, issuing repeated calls for the death of French citizens and the destruction of their assets and interests in northern Africa. The origin for this lies in both AQIM’s relative isolation from al-Qaeda-Central and in the bitter experience of French colonial rule in Algeria, culminating in the brutal 1954-62 struggle for independence (inspired to a large degree by the success of the Marxist Viet Minh’s armed rejection of French colonialism in Indo-China). The Algerian independence movement was a product of its time, and identified closely with the secular socialism promoted by China, the Soviet Union and influential anti-colonial theorists such as Franz Fanon, marginalizing more Islamic trends of resistance in the process. These trends became submerged in Algeria, where they became a type of unofficial opposition to Algeria’s growing authoritarianism and reliance on the military to preserve the post-independence regime. When a brief experiment with multi-party democracy appeared to be leading to an Islamist government in the 1991-92 elections, the regime promptly cancelled the elections, allegedly at the instigation of Paris. As a consequence, Abu Ubaydah refers to the Algerian regime as “the sons of France”. The Islamists launched a new insurgency whose vicious and callous treatment of innocent civilians (possibly with the participation of government-allied provocateurs) eventually led to a crisis within the armed Islamist movement and an eventual identification with the ideals of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda movement that led to the creation in 2007 of an Algerian-based affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

Due to its unique history and antecedents, AQIM is more likely to incorporate more traditional strains of anti-colonial thought into its messaging than other al-Qaeda affiliates in which historical references tend to hearken back to the glorious days of the mediaeval Islamic Empire rather than the more ideologically problematic colonial era. In the fierce fighting for Benghazi, it is somewhat natural then that AQIM ideologues like Abu Ubaydah would be more likely to turn to more-recent resistance leaders like Omar al-Mukhtar for inspiration than their fellow al-Qaeda affiliates.

Notably, Abu Ubaydah singles out French support for anti-terrorist operations in Benghazi, failing to note that the vast majority of those fighting and dying to retake the city from Islamist extremists are in fact Libyan Muslims. Though progress is slow, the ultimate defeat of the extremists (who have little popular support) seems certain – al-Ubaydah’s message is therefore not entirely focused on rallying his Islamist comrades, but also on persuading Benghazi’s Libyan assailants to abandon efforts to seize those parts of the city still under IS/Ansar al-Shari’a control.

The Italian Legacy

In response to the alleged presence of a small number of Italian Special Forces operatives in Libya, Abu Ubaydah claimed in a January audio message entitled “Roman Italy has occupied Libya” that the Italians had re-occupied Libya: “To the new invaders, grandchildren of Graziani, you will bite your hands off, regretting you entered the land of Omar al-Mukhtar and you will come out of it humiliated.”[4] Abu Ubaydah consciously usurped al-Mukhtar’s famous slogan “We will win or die” in his message in an attempt to align AQIM with the Islamist forces in Libya: “We are people who never give up, you will have to walk on our dead bodies. Either we win or we die.”[5] AQIM first encouraged the Libyan thuwar (revolutionaries) to use the slogan in a 2011 message addressed to “the progeny of Omar al-Mukhtar.” [6]

In a further effort to compare the current struggle with al-Mukhtar’s anti-Italian revolt, the AQIM leader also referred to “an Italian general who now rules in Tripoli,” likely describing Italy’s General Paolo Serra, a veteran of Kosovo and Afghanistan and currently the military advisor to Martin Kobler, the UN’s special envoy to Libya.[7]

In March, Abu Ubaydah again referred to “the re-colonization of Libya, now ruled by an Italian general from Tripoli.” He went on to describe how colonialism had returned to North Africa:

After the Arab revolutions and the fall of dictatorships, the West cross saw the return of Muslims to their religion and their commitment to implement sharia, he added. He had no choice but to re-colonize their territory, get hold of their resources and the oil that continues its domination and our marginalization.[8]

New Mausoleum of Marshall Graziani

New Mausoleum of Marshall Graziani

In an entirely different approach to Italy’s colonial legacy, Graziani, a convicted war criminal who flew to Libya to interview al-Mukhtar before his execution, was recently honored with a taxpayer-funded mausoleum and memorial park south of Rome.[9] Through his enthusiastic use of poison gas, chemical warfare, civilian massacres and massive concentration camps to impose Italian rule in Africa, Graziani gained the undesirable distinction of being remembered in Libya as “the Butcher of Fezzan” and in the Horn of Africa as “the Butcher of Ethiopia.”

Operation Volcano of Rage

An Islamist relief column of thirty to forty vehicles seems to have been spurred to relieve Benghazi not by al-Qaeda’s Abu Ubaydah, but rather by Libya’s Chief Mufti, Shaykh Sadiq al-Ghariani, under whose authority they claim to be fighting. The Shaykh has been Libya’s top religious cleric since February 2012, but has since become a divisive political figure generally siding with the Tripoli-based General National Congress government, also supported by Ansar al-Shari’a and the rest of the Shura Council of Bengazhi Revolutionaries.

The self-styled Benghazi Defense Brigade (BDB) began its march on Benghazi (named “Operation Volcano Rage) in late June by warning all residents of towns between Ajdabiya and Benghazi to stay out of their way or face destruction.[10] Nonetheless, the BDB had difficulty getting past Ajdabiya, where they met resistance from the LNA. Clashes around Ajdabiya were said to be responsible for disabling pumps in the Great Man-Made River Project that supplies water to Benghazi, which is already suffering from power cuts seven to eight hours a day.[11]

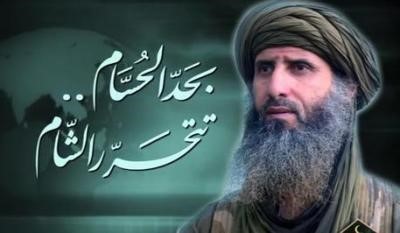

BDB Leader Brigadier Mustafa al-Sharkasi

BDB Leader Brigadier Mustafa al-Sharkasi

The alleged leader of the BDB offensive is Misrata’s Brigadier Mustafa al-Sharkasi. Other leading Islamist militants said to be with the BDB column include al-Sa’adi al-Nawfali of the Adjdabiya Shura Council, Ziyad Balham, the commander of Benghazi’s Omar al-Mukhtar Brigade and Ismail al-Salabi, commander of the Rafallah Sahati militia and brother of prominent Libyan Muslim Brotherhood member Ali Muhammad al-Salabi.

The Grand Mufti’s intervention in the ongoing battle for Benghazi is not surprising; al-Ghariani has in the past referred to those serving under General Haftar as “infidels” and has denied Ansar al-Shari’a is a terrorist group: “There is no terror in Libya and we should not use the word terrorism when referring to Ansar al-Shari’a. They kill and they have their reasons.”[12] Al-Ghariani also declared “the real battle in Libya is the one against Haftar. Only when he is defeated will Libya find security and stability.”[13] The BDB takes a similar view of General Haftar, accusing him of hiring mercenaries and collaborating with former regime members to kill innocents, steal goods and money, destroy homes and displace thousands of Benghazi residents.[14] Both the BDB and their mentor al-Ghariani profess to be opposed to the Islamic State, with some BDB members and leaders having fought the group around Sirte as part of the GNC’s Operation Dawn.

Usama Jadhran (al-Jazeera)

Usama Jadhran (al-Jazeera)

Despite a string of victory announcements by the LNA, the BDB still appears to be active some 30 km south of Benghazi (particularly in the region between Sultan and Suluq) as it continues to try to batter its way into the city. A sensational LNA pronouncement on July 10 claimed LNA airstrikes and attacks had devastated the BNB column, with radical Islamist Usama Jadhran (brother of powerful Petroleum Facilities Guard chief Ibrahim Jadhran) being killed and BNB commander al-Sharkasi being captured and removed to General Haftar’s headquarters. To date, the LNA have yet to confirm these claims, while the BNB insists al-Sharkasi remains free and that the BNB had actually overrun an LNA camp at al-Jalidiya on July 10, capturing significant arms and munitions.[15]

Conclusion

Drawing on the radical inspiration of Egypt’s Sayyid Qutb, al-Qaeda rejects independent Muslim nation-states as long as they continue to adopt the forms of governance introduced by colonial regimes rather than governance drawn strictly from Shari’a in its Salafist interpretation, i.e. the sovereignty of God (al-hakimiya li’llah) over the sovereignty of man. Until this is achieved, according to Qutb, Muslim society will continue to exist in a state of jahiliya (the state of ignorance that prevailed in pre-Islamic society). Though the Grand Mufti’s appeals for anti-LNA intervention in Benghazi have had some limited success, calls from Abu Ubaydah for Muslims to flock to the aid of Benghazi’s hard-pressed Islamist militants have produced not even a noticeable trickle in comparison, suggesting that AQIM’s desire to influence Libya’s future remains largely disconnected most of the diverse political and religious approaches favored by Libya’s Muslims. Abu Ubaydah’s attempt to invoke the spirit of Omar al-Mukhtar to rally support for Benghazi’s Islamist militants is more likely to remind most Libyans of the abuse al-Mukhtar’s legacy suffered under Qaddafi than it is to launch new waves of dedicated jihadists. Unlike Abu al-Ubaydah, Omar al-Mukhtar did not need to invent an Italian occupation of Libya to rally his people against colonialism.

This article was originally published at: http://www.trackingterrorism.org/article/al-qaeda-anti-colonialism-and-battle-benghazi/executive-summary

NOTES

[1] Libya Herald, June 27, 2016, https://www.libyaherald.com/2016/06/27/substantial-bombardment-of-benghazi-terrorist-positions/.

[2] Abu Mu`sab Abd al-Wadud, “Aid to the Noble Descendants of Umar al-Mukhtar,” Ansar1.info, March 18, 2011. For a discussion of these efforts, see Barak Barfi: “Al-Qa’ida’s Confused Messaging on Libya,” Center for Countering Terrorism, West Point N.Y., August 1, 2011, https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/al-qaida%E2%80%99s-confused-messaging-on-libya ; Abu Ubaydah Yusuf al-Anabi: “The War on Mali,” April 25, 2013, http://www.as-ansar.com/vb/showthread.php?t=88988.

[3] Ansar1.info, March 12, 2011 (no longer available on the web).

[4] ANSA [Rome], January 14, 2016, http://www.ansa.it/english/news/world/2016/01/14/al-qaeda-threatens-italy_bf3677bf-a525-45c2-ab8a-9d39f8fc448a.html .

[5] ANSA, January 14, 2016, http://www.ansa.it/english/news/world/2016/01/14/al-qaeda-threatens-italy_bf3677bf-a525-45c2-ab8a-9d39f8fc448a.html.

[6] Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, “In Defense and Support of the Revolution of Our Fellow Free Muslims, the Progeny of Omar al-Mukhtar,” al-Andalus Media Foundation, February 23, 2011; English translation available here: http://occident2.blogspot.ca/2011/02/english-al-qaida-in-islamic-maghreb_27.html

[7] ANSA, January 14, 2016, http://www.ansa.it/english/news/world/2016/01/14/al-qaeda-threatens-italy_bf3677bf-a525-45c2-ab8a-9d39f8fc448a.html.

[8] Al-Akhbar [Nouakchott], March 7, 2016, http://fr.alakhbar.info/10874-0-Aqmi-Laccord-inter-libyen-est-un-complot-italien.html .

[9] BBC, August 15, 2012, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-19267099 .

[10] Libya Herald, June 19, 2016, https://www.libyaherald.com/2016/06/19/new-benghazi-militant-unit-issues-ajdabiya-warning/.

[11] Libya Herald, June 20, 2016, https://www.libyaherald.com/2016/06/20/benghazi-without-water-following-power-cuts-to-soloug-reservoir-tripoli-in-fourth-day-of-water-shortages/.

[12] Magharebia, June 12, 2014, http://allafrica.com/stories/201406130754.html.

[13] Libyan Gazette, June 13, 2016, https://www.libyangazette.net/2016/06/13/grand-mufti-of-libya-calls-on-libyan-army-to-move-on-to-benghazi-after-defeating-isis/.

[14] Libya Observer, June 22, 2016, http://www.libyaobserver.ly/news/brigadier-al-shirksi-we-are-not-warmongers-we-came-defend-benghazi; July 12, 2016, http://www.libyaobserver.ly/news/defend-benghazi-brigades-our-battle-aims-regain-rights-displaced-and-thwart-haftar%E2%80%99s-project.

[15] Libya Herald, July 17, 2016, https://www.libyaherald.com/2016/07/17/police-arrest-alleged-bdb-supporters-in-soloug-and-yemenis-report/ ; July 10, 2016, https://www.libyaherald.com/2016/07/10/army-claims-capture-of-sharksi-his-bdb-militia-deny-it/; Libya Observer, July 10, 2016, http://www.libyaobserver.ly/news/defend-benghazi-brigades-confirm-control-sultan-district-western-benghazi.

Chinese Wing Loong II Drone (Dafz.org)

Chinese Wing Loong II Drone (Dafz.org) Wreckage of the UAE Wing Loong II Drone Downed Near Misrata (SouthFront.org)

Wreckage of the UAE Wing Loong II Drone Downed Near Misrata (SouthFront.org) Destroyed Ilyushin Transports in al-Jufra (Avia.pro)

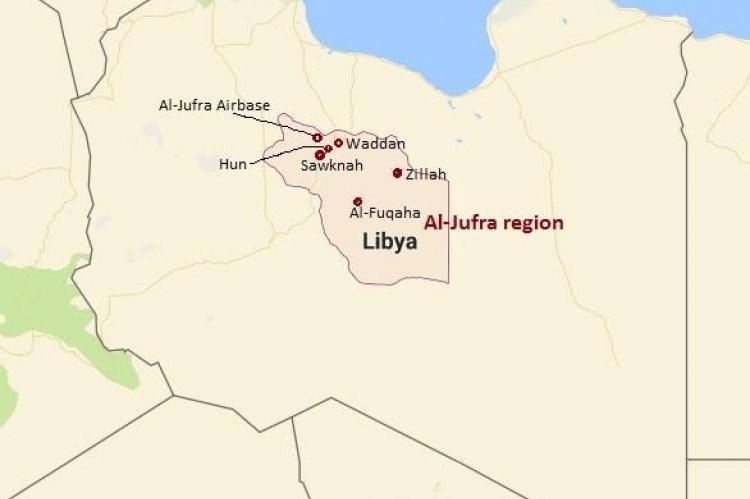

Destroyed Ilyushin Transports in al-Jufra (Avia.pro) Al-Jufra Region and Airbase (Libya Observer)

Al-Jufra Region and Airbase (Libya Observer) UAE Russian-Made Pantsir S1 Air Defense System in Yemen – Now in Use by the LNA? (Defense-Blog.com)

UAE Russian-Made Pantsir S1 Air Defense System in Yemen – Now in Use by the LNA? (Defense-Blog.com)