Andrew McGregor

April 16, 2016

After taking the throne in January, the new Saudi regime of King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud seems determined to shake off the perceived lethargy of the Saudi royals, presenting a more vigorous front against a perceived Shi’a threat in the Gulf with the appointment of former Interior Minister Muhammad bin Nayef as Crown Prince and Salman’s son Muhammad as Minister of Defense and second in line to the throne. To contain Shiite expansion in the Gulf region, the Saudis created a coalition of Muslim countries last year to combat Yemen’s Zaydi Shiite Houthi movement, which had displaced the existing government and occupied Yemen’s capital in 2014. Assessing the military performance of this coalition is useful in projecting the performance of an even larger Saudi-led “counter-terrorist” coalition designed to intervene in Syria and elsewhere.

Saudi Border Post Overlooking Yemen

Saudi Border Post Overlooking Yemen

As a demonstration of the united military will of 20 majority Sunni nations (excluding Bahrain, which has a Shi’a majority but a Sunni royal family), the Saudi-led Operation Northern Thunder military exercise gained wide attention during its run from February 14 to March 10 (Middle East Monitor, March 3, 2016).[1] The massive exercise involved the greatest concentration of troops and military equipment in the Middle East since the Gulf War. However, Saudi ambitions run further to the creation of an anti-terrorism (read anti-Shi’a) coalition of 35 Muslim nations that is unlikely to ever see the light of day as conceived. Questions were raised regarding the true intent of this coalition when it became clear Shi’a-majority Iran and Iraq were deliberately excluded, as was Lebanon’s Shi’a Hezbollah movement.

Coalition Operations in Yemen

A Saudi-led coalition launched Operation Decisive Storm in Yemen on March 26, 2015 as a means of reversing recent territorial gains by the Zaydi Shi’a Houthi movement, securing the common border and restoring the government of internationally recognized president Abd Rabu Mansur al-Hadi, primarily by means of aerial bombardment.

Nine other nations joined the Saudi-coalition; the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and Senegal, the latter being the only non-Arab League member. Senegal’s surprising participation was likely the result of promises of financial aid; Senegal’s parliament was told the 2,100 man mission was aimed at “protecting and securing the holy sites of Islam,” Mecca and Madinah (RFI, March 12, 2015).

Despite having the largest army in the coalition, Egypt’s ground contributions appear to have been minimal, with the nation still wary of entanglement in Yemen after the drubbing its expeditionary force took from Royalist guerrillas in Yemen’s mountains during the 1962-1970 civil war, a campaign that indirectly damaged Egypt’s performance in the 1973 Ramadan War against Israel. The Egyptians have instead focused on contributing naval ships to secure the Bab al-Mandab southern entrance to the Red Sea, a strategic priority for both Egypt and the United States.

With support from the UK and the United States, the Saudi-led intervention was seen by Iran, Russia and Gulf Shiite leaders as a violation of international law; more important, from an operational perspective, was the decision of long-time military ally Pakistan to take a pass on a Saudi invitation to join the conflict (Reuters, April 10, 2015).

Operation Decisive Storm was declared over on April 21, 2015, to be replaced the next day with Operation Restoring Hope. Though the new operation was intended to have a greater political focus and a larger ground component, the aerial and naval bombing campaign and U.S.-supported blockade of rebel-held ports continued.

The failure of airstrikes alone to make significant changes in military facts on the ground was displayed once again in the Saudi-led air campaign. A general unconcern for collateral damage, poor ground-air coordination (despite Western assistance in targeting) and a tendency to strike any movement of armed groups managed to alienate the civilian population as well as keep Yemeni government troops in their barracks rather than risk exposure to friendly fire in the field (BuzzFeed, April 2, 2015). At times, the airstrikes have dealt massive casualties to non-military targets, including 119 people killed in an attack on a market in Hajja province in March 2016 and a raid on a wedding party in September 2015 that killed 131 people (Guardian, March 17, 2016).

While coalition operations have killed some 3,000 militants, the death of an equal number of civilians, the use of cluster munitions and the destruction of infrastructure, mosques, markets, heritage buildings, residential neighborhoods, health facilities, schools and other non-military targets constitute a serious mistake in counter-insurgency operations. Interruptions to the delivery of food, fuel, water and medical services have left many Yemenis prepared to support whomever is able to provide essential services and a modicum of security.

A Muslim Army or an Army of Mercenaries?

When the population of Germany’s small states began to grow in the late 18th century, the rulers of duchies and principalities such as Hesse, Hanover, Brunswick found it both expedient and profitable to rent out their small but highly-trained armies to Great Britain (whose own army was extremely small) for service in America, India, Austria, Scotland, and Ireland. Similarly, a number of Muslim-majority nations appear to be contributing troops to the Saudi-led coalition in return for substantial financial favors from the Saudi Kingdom.

Khartoum’s severance of long-established military and economic relations with Iran has been followed by a much cozier and financially beneficial relationship with Saudi Arabia (much needed after the loss of South Sudan’s oilfields). Sudan committed 850 troops (out of a pledged 6,000) and four warplanes to the fighting in Yemen; like the leaders of other coalition states, President Omar al-Bashir justified the deployment in locally unchallengeable terms of religious necessity – the need to protect the holy places of Mecca and Madinah, which are nonetheless not under any realistic threat from Houthi forces (Sudan Tribune, March 15, 2016).

Khartoum was reported to have received a $1 billion deposit from Qatar in April 2015 and another billion in August 2015 from Saudi Arabia, followed by pledges of Saudi financing for a number of massive Sudanese infrastructure projects (Gulf News, August 13, 2015; East African [Nairobi], October 31, 2015; Radio Dabanga, October 4, 2015). Sudanese commitment to the Yemen campaign was also rewarded with $5 billion worth of military assistance from Riyadh in February, much of which will be turned against Sudan’s rebel movements and help ensure the survival of President Bashir, wanted by the International Criminal Court for genocide and crimes against humanity (Sudan Tribune, February 24, 2016). Some Sudanese troops appear to have been deployed against Houthi forces in the highlands of Ta’iz province, presumably using experience gained in fighting rebel movements in Sudan’s Nuba Hills region (South Kordofan) and Darfur’s Jabal Marra mountain range.

The UN’s Somalia-Eritrea Monitoring Group (SEMG) cited “credible information” this year that Eritrean troops were embedded in UAE formations in Yemen, though this was denied by Eritrea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (Geeska Afrika Online [Asmara], February 23). The SEMG also reported that Eritrea was allowing the Arab coalition to use its airspace, land territory and waters in the anti-Houthi campaign in return for fuel and financial compensation. [2] Somalia accepted a similar deal in April 2015 (Guardian, April 7, 2015).

UAE troops, mostly from the elite Republican Guard (commanded by Austrian Mike Hindmarsh) have performed well in Yemen, particularly in last summer’s battle for Aden; according to Brigadier General Ahmad Abdullah Turki, commander of Yemen’s Third Brigade: “Our Emirati brothers surprised us with their high morale and unique combat skills,” (Gulf News, December 5, 2015). The UAE’s military relies on a large number of foreign advisers at senior levels, mostly Australians (Middle East Eye, December 23, 2015). Hundreds of Colombian mercenaries have been reported fighting under UAE command, with the Houthis reporting the death of six plus their Australian commander (Saba News Agency [Sana’a], December 8, 2015; Colombia Reports [Medellin], October 26, 2015; Australian Associated Press, December 8, 2015).

There is actually little to be surprised about in the coalition’s use of mercenaries, a common practice in the post-independence Gulf region. A large portion of Saudi Arabia’s combat strength and officer corps consists of Sunni Pakistanis, while Pakistani pilots play important roles in the air forces of both Saudi Arabia and the UAE. As well as the Emirates, Oman and Qatar have both relied heavily on mercenaries in their defense forces and European mercenaries played a large role in Royalist operations during North Yemen’s 1962-1970 civil war.

Insurgent Tactics

The Houthis have mounted near-daily attacks on Saudi border defenses, using mortars, Katyusha and SCUD rockets to strike Saudi positions in Najran and Jizan despite Saudi reinforcements of armor, attack helicopters and National Guard units. Little attempt has been made by the Houthis to hold ground on the Saudi side of the border, which would only feed Saudi propaganda that the Shiites are intent on seizing the holy cities of the Hijaz.

When Republican Guard forces loyal to ex-president Ali Abdullah Saleh joined the Houthi rebellion, they brought firepower previously unavailable to the Houthis, including the Russian-made OTR-21 mobile missile system. OTR-21 missiles have been used in at least five major strikes on Saudi or coalition bases, causing hundreds of deaths and many more wounded.

Saudi Artillery Fires on Houthi Positions (Faisal al-Nasser, Reuters)

Saudi Artillery Fires on Houthi Positions (Faisal al-Nasser, Reuters)

The Islamic State (IS) has been active in Yemen since its local formation in November 2014. Initially active in Sana’a, the movement has switched its focus to Aden and Hadramawt. IS has used familiar asymmetric tactics in Yemen, assassinating security figures and deploying suicide bombers in bomb-laden vehicles against soft targets such as mosques (which AQAP now refrains from) as well as suicide attacks on military checkpoints that are followed by assaults with small arms. With its small numbers, the group has been most effective in urban areas that offer concealment and dispersal opportunities. Nonetheless, part of its inability to expand appears to lie in the carelessness with which Islamic State handles the lives of its own fighters and the wide dislike of the movement’s foreign (largely Saudi) leadership.

War on al-Qaeda

With control of nearly four governorates, a major port (Mukalla, capital of Hadramawt province) and 373 miles of coastline, al-Qaeda has created a financial basis for its administration by looting banks, collecting taxes on trade and selling oil to other parts of fuel-starved Yemen (an unforeseen benefit to AQAP of the naval blockade). The group displayed its new-found confidence by trying (unsuccessfully) to negotiate an oil export deal with Hadi’s government last October (Reuters, April 8, 2016).

Eliminating al-Qaeda’s presence in Yemen was not a military priority in the Saudi-led campaign until recently, with an attack by Saudi Apache attack helicopters on AQAP positions near Aden on March 13 and airstrikes against AQAP-held military bases near Mukalla that failed to dislodge the group (Reuters, March 13; Xinhua, April 3, 2016).

Perhaps drawing on lessons learned from al-Qaeda’s failed attempt to hold territory in Mali in 2012-2013, AQAP in Yemen has focused less on draconian punishments and the destruction of Islamic heritage sites than the creation of a working administration that provides new infrastructure, humanitarian assistance, health services and a degree of security not found elsewhere in Yemen (International Business Times, April 7, 2016).

Conclusion: A Saudi-led Coalition in Syria?

The Saudis are now intent on drawing down coalition ground operations while initiating new training programs for Yemeni government troops and engaging in “rebuilding and reconstruction” activities (al-Arabiya, March 17, 2016). A ceasefire took hold in Yemen on April 10 in advance of UN-brokered peace talks in Kuwait to begin on April 18. Signs that a political solution may be at hand in Yemen include Hadi’s appointment of a new vice-president and prime minister, the presence of a Houthi negotiating team in Riyadh and the exclusion of ex-president Saleh from the process, a signal his future holds political isolation rather than a return to leadership (Ahram Online, April 7, 2016).

If peace negotiations succeed in drawing the Houthis into the Saudi camp the Kingdom will emerge with a significant political, if not military, victory, though the royal family will still have an even stronger AQAP to contend with. Like the Great War, the end of the current war in Yemen appears to be setting the conditions for a new conflict so long as it remains politically impossible to negotiate with AQAP. However, AQAP is taking the initiative to gain legitimacy by testing new names and consolidating a popular administration in regions under its control. Unless current trends are reversed, AQAP may eventually be the first al-Qaeda affiliate to successfully make the shift from terrorist organization to political party.

The cost to the Saudis in terms of cash and their international reputation has been considerable in Yemen, yet Hadi, recently fled to Riyadh, is no closer to ruling than when the campaign began. Sana’a remains under Houthi control and radical Islamists have taken advantage of the intervention to expand their influence. Perhaps in light of this failure, Saudi foreign minister Adl al-Jubayr has suggested the Kingdom now intends only a smaller Special Forces contribution to the fighting in Syria that would focus not on replacing the Syrian regime but rather on destroying Islamic State forces “in the framework of the international coalition” (Gulf News, February 23, 2016). Introducing a larger Saudi-led coalition to the anti-Islamic State campaign in Syria/Iraq without a clear understanding and set of protocols with other parties involved (Iran, Iraq, Russia, Hezbollah, the Syrian Army) could easily ignite a greater conflict rather than contribute to the elimination of the Islamic State. Saudi Arabia is not a disinterested party in the Syrian struggle; it has been deeply involved in providing financial, military and intelligence support to various religiously-oriented militias that operate at odds with groups supported by other interested parties.

The Saudi-led intervention in Yemen has left one of the poorest nations on earth in crisis, with 2.5 million displaced and millions more without access to basic necessities. With Yemen’s infrastructure and heritage left in ruins and none of the coalition’s strategic objectives achieved, it seems difficult to imagine that the insertion into Syria of another Saudi-led coalition would make any meaningful contribution to bringing that conflict to a successful or sustainable end.

Notes

- Besides Saudi Arabia, the other nations involved in the exercise included Egypt, Jordan, Senegal, Sudan, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Pakistan, Chad, Tunisia, Djibouti, Comoro Islands and Peninsula Shield Force partners Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

- Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea pursuant to Security Council resolution 2182 (2014): Eritrea, October 19, 2015, 3/93, http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2015/802

An edited version of this article appeared in the April 15, 2016 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor under the title: “Saudi Arabia’s Intervention in Yemen Suggests a Troubled Future for the Kingdom’s Anti-Terror Coalition,” http://www.jamestown.org/programs/tm/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=45324&tx_ttnews[backPid]=26&cHash=e2d5de949e926ff3b5d9228dc4b96af7#.VxfvSkdqnIU

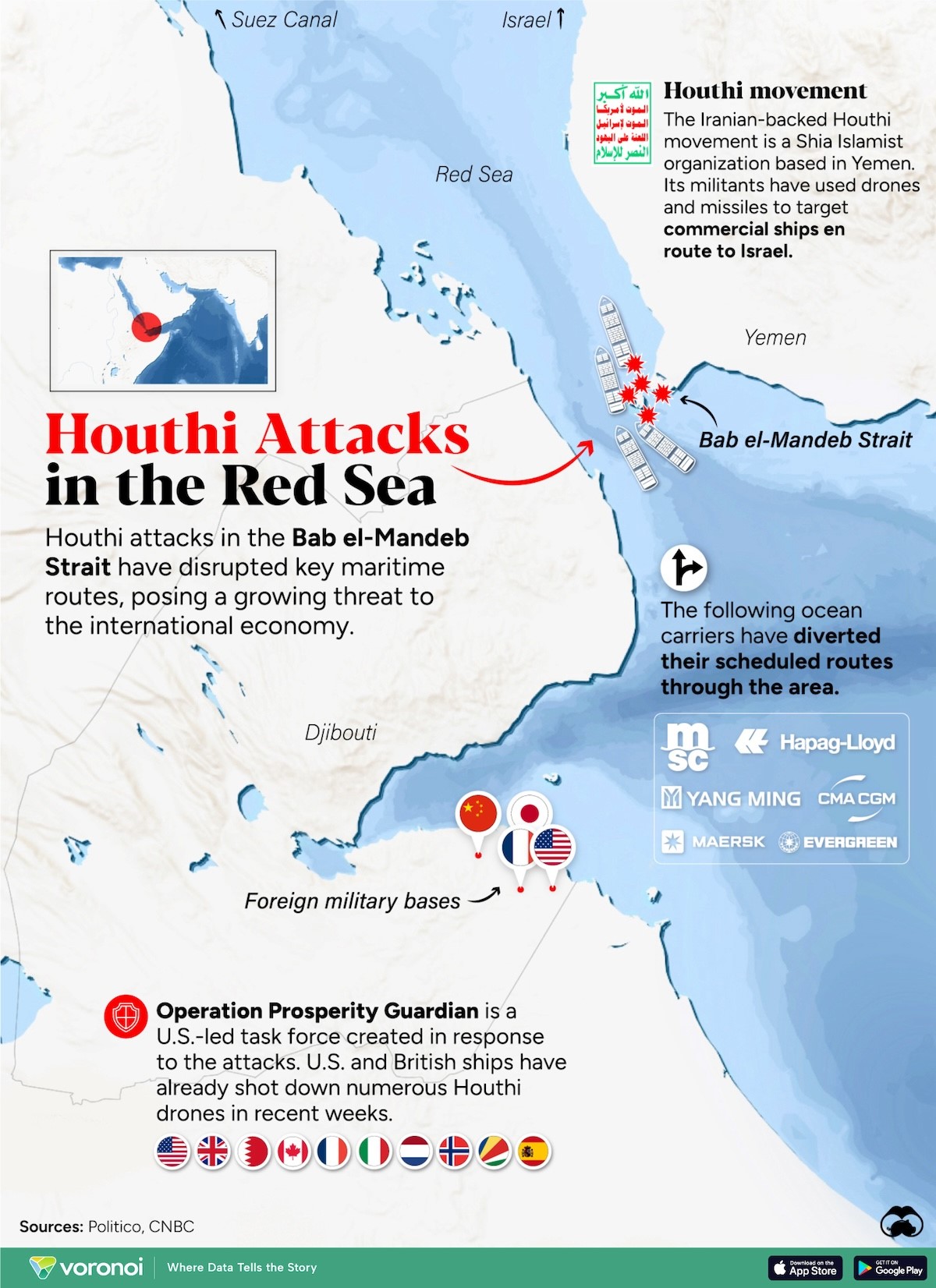

On August 2, a senior US official reported that members of the Main Directorate of the Russian General Staff (GRU) are operating in the Houthi-controlled territory of Yemen in an advisory role to Yemen’s Houthi movement, Ansarallah. The report claims that GRU officers have been operating in Yemen for “several months” to assist the Houthis in targeting commercial shipping (Middle East Eye, August 2). Ansarallah has been striking shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden for over eight months in support of Gaza’s Hamas movement. Primarily using drones and missiles provided by Iran, the Houthi attacks are intended to interfere with the movement of Israeli ships or cargoes, as well as those of Israel’s main backers, the United States and the United Kingdom. The latter two powers also provide military aid and intelligence to Ukraine in its resistance to the Russian invasion. When the United States gave Kyiv permission to use new weapons provided by the US-led Western alliance to strike targets inside Russia, Moscow began to consider striking back on a new front by providing modern anti-ship missiles to Yemen’s Houthis (Middle East Eye, June 28). The provision of sophisticated arms for Houthi use against Western shipping would represent a dangerous expansion of the conflict in Ukraine that could not easily be reversed.

On August 2, a senior US official reported that members of the Main Directorate of the Russian General Staff (GRU) are operating in the Houthi-controlled territory of Yemen in an advisory role to Yemen’s Houthi movement, Ansarallah. The report claims that GRU officers have been operating in Yemen for “several months” to assist the Houthis in targeting commercial shipping (Middle East Eye, August 2). Ansarallah has been striking shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden for over eight months in support of Gaza’s Hamas movement. Primarily using drones and missiles provided by Iran, the Houthi attacks are intended to interfere with the movement of Israeli ships or cargoes, as well as those of Israel’s main backers, the United States and the United Kingdom. The latter two powers also provide military aid and intelligence to Ukraine in its resistance to the Russian invasion. When the United States gave Kyiv permission to use new weapons provided by the US-led Western alliance to strike targets inside Russia, Moscow began to consider striking back on a new front by providing modern anti-ship missiles to Yemen’s Houthis (Middle East Eye, June 28). The provision of sophisticated arms for Houthi use against Western shipping would represent a dangerous expansion of the conflict in Ukraine that could not easily be reversed. Oil tanker Chios Lion, carrying Russian oil to China, is attacked by a Houthi missile on July 15, 2024 (Yemeni Military Media).

Oil tanker Chios Lion, carrying Russian oil to China, is attacked by a Houthi missile on July 15, 2024 (Yemeni Military Media).