AIS Special Report on Ukraine No. 4

April 7, 2022

Andrew McGregor

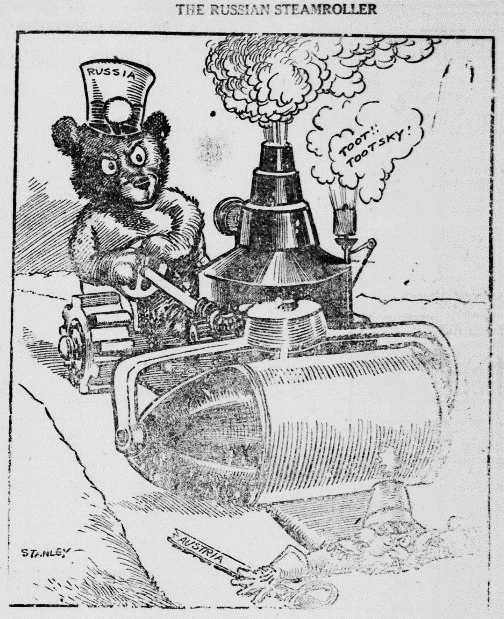

Strategic speculation regarding a potential clash of European powers in the early 20th century often cited the likely impact of “the Russian Steamroller,” referring to the massive Imperial Russian army of 1.4 million men and a reserve of over 3 million more. Despite a surprisingly poor performance against Japan in 1904-05, the spectre of millions of armed Russians rolling across Europe in an irresistible wave still figured into the military calculations of other European powers. When a European war did break out in 1914, a smaller German force quickly destroyed the invading Russian masses around the lakes of East Prussia. New armies were raised from the seemingly endless manpower of Russia and some 15 million Russians eventually passed through the army ranks, leaving two million dead on the battlefields of Eastern Europe before Russia made an early exit from the conflict.

Strategic speculation regarding a potential clash of European powers in the early 20th century often cited the likely impact of “the Russian Steamroller,” referring to the massive Imperial Russian army of 1.4 million men and a reserve of over 3 million more. Despite a surprisingly poor performance against Japan in 1904-05, the spectre of millions of armed Russians rolling across Europe in an irresistible wave still figured into the military calculations of other European powers. When a European war did break out in 1914, a smaller German force quickly destroyed the invading Russian masses around the lakes of East Prussia. New armies were raised from the seemingly endless manpower of Russia and some 15 million Russians eventually passed through the army ranks, leaving two million dead on the battlefields of Eastern Europe before Russia made an early exit from the conflict.

Russia’s disastrous role in the Great War contributed to a civil war and an earth-shaking post-war political change that saw Tsars and princes replaced with Bolsheviks and commissars. Though the army of the new Soviet Union remained huge, its equipment was poor and its timid leadership was all that was left after Stalin’s pre-war purge of “anti-revolutionary” elements in the officer corps. This encouraged Germany to tackle the “Steamroller” head-on once again in 1941. Despite its numbers, the almost leaderless Red Army collapsed and the Germans were within sight of Moscow before the army’s headlong retreat could be halted. Germany ultimately lost the war in the East (in large part due to massive Allied aid to Moscow), but not before it succeeded in killing some ten million Soviet soldiers out of the 26 million that served in the wartime Red Army.

Mass Soviet armies threatened Europe throughout the Cold War, but the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 left the military divided and confused regarding its composition and role. Since the beginning of the Cold War, the military goal of the Soviets and their Russian successors has been to field an army capable of taking on American forces (and their NATO allies) while spending a mere fraction of the US military budget. Needless to say, this is an unrealistic goal and efforts to keep up with American military spending have already broken the Kremlin’s bank once before.

Embarrassing defeats at the hands of Chechen resistance fighters in the 1990s helped bring internal recognition that reforms were badly needed in the Russian army. Poorly trained conscripts performed so ineptly in the Caucasus that frontline officers begged to be spared further reinforcements of draftees.

Russia thus began a gradual transformation to a more professional force with a focus on elite elements rather than the massed armies that had served Russia in the past. However, efforts to build a smaller and more professional military continue to be held back by Russia’s perceived need to field forces large enough to engage with its strategic “peers” in Europe. The financial inability of Russia to fund an army with training, armament and numbers comparable to NATO forces while also maintaining expensive elite forces has led to imbalances in the structure of the Russian Army, imbalances that sabotaged Moscow’s plans for a quick and decisive victory in Ukraine.

Unexpectedly forced into a conventional war unlike the lightning strike by elite troops that Moscow had planned for, Russia’s military seems unable to overcome resistance from a much smaller army, even with the benefit of short supply lines and a huge superiority in arms, armor, aircraft and weapons systems. So what is wrong with the Russian Army?

Not anticipating a campaign of any length, Russia did not field its army in the usual way as brigades, divisions and armies, deploying its forces instead in the battalion tactical groups (BTGs) the army has favored for use in the Donbas region. The BTGs, which focus on mobility backed by artillery, do not carry the same level of battlefield maintenance and repair support services as the larger formations, partly explaining the logistical problems experienced after Russia’s “special military operation” failed to take out the Zelensky government in the first 48 hours (ECFR, March 15, 2022). Roughly 125 BTGs have been deployed in Ukraine.

The new focus on elite troops and the common practice of scripting large-scale military exercises in peacetime have damaged the army’s ability to fight in a conventional manner. Poor land-air coordination of Russian forces prevents effective offensive airstrikes with confusion prevailing over the identification of ground forces as friend or foe. Wretched staff-work and military intelligence efforts bordering on outright incompetence speak to the neglect and lethargy still common to large parts of the Russian military. A basic inability to identify useful military targets may be contributing to the Russian destruction of civilian targets throughout Ukraine.

The Russian army also seems to be unable to use drones to their full advantage in pressing home their attacks. Ukraine’s use of Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones has been much more effective in comparison, taking full advantage of the Russian invasion’s reliance on roads and rail to move men and materiel at this time of year.

It is noteworthy that no single general appears to be in command of the campaign, partly due to the Kremlin’s reluctance to elevate operations in Ukraine in the public eye to the status of an “invasion” or “war,” terms that have actually been banned from public discussion of the operation. Confident of a quick victory, Putin may have decided to retain overall command for himself in order to claim credit for a legacy-building contribution to the reconstruction of the Soviet Empire so mourned by the Russian president. Putin has not, however, admitted to any responsibility for a war that has badly damaged Russia’s economy, exposed its military and battered its international reputation.

General Valery Gerasimov (CNBC)

General Valery Gerasimov (CNBC)

Despite being the author of Russia’s central military doctrine, commander of the Russian Armed Forces General Valery Gerasimov briefly went missing from public view after March 11, along with Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and intelligence chiefs Igor Kostyukov (GRU) and Alexander Bortnikov (FSB). The FSB, responsible for domestic intelligence, has a clandestine foreign intelligence branch that was responsible for forming partisan groups and encouraging public support for the invasion in Ukraine, failing dismally on both counts. Shoigu and Gerasimov reappeared in a March 26 press conference, but it is unclear whether the two are still actively in command of Russian operations in Ukraine. Putin’s dissatisfaction with the efforts of his military and intelligence leaders became obvious in his March 16 declaration, when he warned the Russian nation will distinguish between true patriots and “scum and traitors” who will be dealt with in a Stalin-style purge.

THE PROFESSIONALS – THE CONTRACT CORE OF THE RUSSIAN ARMY

Conscript losses in the Chechen wars hastened the implementation of proposals to develop a professional corps of volunteer soldiers under three-year, renewable contracts. The kontraktniki, as the contract troops are known, now form two-thirds of Russia’s 600,000-man army and enjoy far better conditions and benefits than conscript troops. Proposals to further expand the contract force continue to founder on the financial difficulty of paying contractors 30 times what a conscript is paid (plus benefits and pensions).

Citizens of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) were first given the opportunity of enlisting in the Russian army in January 2004. According to new rules introduced in 2010 aimed at addressing the unpopularity of military service in Russia, citizens of the CIS were allowed to sign a five-year military service contract, with the possibility of obtaining Russian citizenship after three years. [1] Recruitment began to intensify in the Northern Caucasus and Central Asian states, where military service was still seen as a traditional and honorable occupation offering opportunities of advancement. Enlistment also proved popular with ethnic Ukrainians; a breakdown of ethnic origins in the Russian Federation Army in 2018 revealed over half the officers in the army at that time were ethnic Ukrainians (Newizv.ru, February 28, 2022).

Russia often has difficulty convincing contract soldiers to renew their three-year deal in the best of times; convincing kontraktniki whose contracts are expiring to sign up for another hitch during the dirty and demoralizing war in Ukraine may prove a challenge. Little attention has been given to the proper training of non-commissioned officers (NCOs), leaving the lower ranks more dependent on junior officers for initiative and leadership. Russia has, however, revived the controversial post of “political commissar,” albeit in a new form, with lessons in Marxist dialectical materialism replaced by instruction in patriotism and devotion to the state. Besides the new focus on patriotism as a core military value, some effort has been made in recent years to alleviate the notoriously brutal conditions of service in the Russian army, including better pay, pensions and improved living quarters.

Much has been made of the experience Russian forces gained in Syria since 2015, but this experience has been limited to elements of the air force, special forces, intelligence services, military police and select naval ships. Russian infantry of the regular forces have not participated in the ongoing conflict in Syria. Ukrainian troops, on the other hand, have been regularly rotated through frontline positions in the Donbas region since 2014, fighting pro-Russian militias and their Russian advisors. Regular exposure to combat no doubt provided motivation in the Ukrainian ranks to absorb the intensive training provided by elite NATO troops for the past seven years.

THE CONSCRIPTS – THE STEAMROLLER ON LIFE SUPPORT

The persistence of conscription in Russia when most competing Western nations have moved entirely to professional volunteer forces reflects both an authoritarian fear of a politicized professional military seizing control and an inability to finance a purely professional force.

The deployment of nearly helpless conscripts against highly-skilled and motivated Chechen resistance forces in the 1990s led to a massive distaste for compulsory service in Russian society. As a result, the armed forces found themselves left with only those not clever enough or wealthy enough to avoid the draft, some even resorting to self-mutilation to avoid service. What was left was the slow-witted, the unhealthy and underweight poor, the drug-addled and drink-besotted and the less-than-patriotic graduates of Russia’s prison system. At one point in the 1990s, the Russian conscription class contained far more ex-convicts than recruits with a higher education. It was unsuitable material with which to build a modern army.

For any recruit holding a misguided belief in a military future, there was the dedovshchina, a deeply ingrained system of violent hazing of first-year conscripts by second-year conscripts that led to thousands of unnecessary deaths every year, including those who looked to suicide as a means of escaping the abuse. While a change to only a single year of conscription and other reforms have helped, the reputation established by this iniquitous tradition continues to deter young Russians from military service. Unfortunately, the dedovshchina is now being replaced by ethnic rivalries in the lower ranks, forcing the command to consider creating ethnically-based units to keep rival groups apart, though this is unlikely to proceed due to Moscow’s traditional suspicion of its national minorities. The army of the Russian Federation is far from homogenously Russian and Christian despite its close alliance with the Russian Orthodox Church; it includes Muslim Tatars, ethnic-Koreans, and Muslims from Central Asia and the North Caucasus, among others.

The army recruits through semi-annual drafts, the spring draft coming on April 1 and the fall draft launching on October 1. In recent years, the annual number of recruits has been between 260,000 to 270,000. Very few, if any, children of the Russian elite are ever absorbed into the service through conscription.

Captured Russian Conscripts in Kiev

Captured Russian Conscripts in Kiev

In 2008, then-Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov promised to stop sending conscripts to “hot-spots” where combat is ongoing and reduced the conscription period from two years to one. With basic and secondary training taking six to seven months, conscripts are only available for service for a few months before finishing their year-long enlistment.

Due to the difficulty in turning low-quality conscripts into active service troops with the short training period (complicated by conscripts’ focus on their release date rather than developing military skills), draftees are typically unable to operate advanced weapons systems and are instead used in more labor-intensive support roles such as wood-cutting, construction, cooking and transportation. For tasks requiring technological skills, contractors are used exclusively.

A March 7 declaration by Putin that no conscripts were currently deployed in Ukraine was followed a day later by an admission by the Ministry of Defense that conscripts were indeed fighting in Ukraine. In Putin’s mind, his claim may have been technically true – there are numerous reports since the beginning of the Ukraine conflict of Russian conscripts nearing the end of their enlistment being forced, even physically, to sign three-year contracts changing their status from conscript to contract soldier. The change in status, however, is no substitute for the additional training and combat experience real contract troops have received. Ultimately, the addition of poorly trained warm bodies to Russian combat units in the middle of a conflict will do little to enhance their effectiveness, though it may keep these units busy chasing deserters.

THE RESERVE – TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Most of Russia’s reserve forces are basically non-functional, with little money available for mobilization, monthly exercises and other training necessary to keep reserve troops in fighting trim. It cannot, therefore, be counted on to replace Russian losses in an extended conflict. Until recently, Russia’s active reserve amounted to only a few thousand soldiers, forcing Moscow to avoid protracted conflicts in which losses could not be easily replaced.

Apparently with an invasion of Ukraine in mind, the Kremlin began to take the problem of the reserves seriously in August 2021. Until that point, reservists were spread out through the country, receiving little or no training. Contact with the armed forces was minimal – reservists were expected to report in themselves in the event of a mobilization and there was no system to keep track of the locations of reservists after they finished their one-year of conscript service. Mobilization of the reserve counted very much on who would feel inclined to show up at the local collection center. By this point, Russia’s armed millions had become little more than a fiction.

To deal with this problem, the Russian command formed the Special Combat Army Reserve (Boevoy Armeyskiy Rezerv Strany – BARS), a kind of reserve form of the kontraktniki, where volunteers with military training could sign three-year contracts, receiving compensation for three-days of training a month. Employers would also be compensated for the loss of labor on service days. The plan was to build a capable reserve of 100,000 troops, likely in preparation for the invasion of Ukraine and possibly other regions on Putin’s “restore the Soviet Union” list.

Vladimir Putin announced on March 8 that Russian reserve troops were not serving in Ukraine, though the announcement came on the heels of Putin’s false assertion that Russian conscripts were not present in Ukraine. Given the intensity of the fighting in Ukraine, it will be impossible to avoid the necessity of temporarily rotating kontraktniki units out of the frontlines; if Russian reserves are not in Ukraine now, they may soon be.

MERCENARIES AND FOREIGN FIGHTERS: WHAT WOULD BREZHNEV SAY?

Russia’s experiment in using private military contractors (PMCs) with close ties to private Russian mining firms and investment companies to extend Russian influence abroad has yielded dividends for the Kremlin. At the same time, it allows Moscow to deny culpability for the war crimes and corrupt practices of these formations. From their early use in Syria and Ukraine’s Donbas region, the PMCs (most notable of which is the notorious “Wagner Group”) have now deployed in Sudan, Mali, Mozambique, Libya and the Central African Republic (CAR), offering military services as well as assistance in electoral manipulation, disinformation campaigns, VIP protection and intimidation operations. This new phase of establishing Russian influence abroad marks a drastic deviation from the Soviet era, when the Soviet Union was one of the firmest opponents of “white mercenaries” in Africa, most of whom were staunch anti-communists and hindrances to the spread of Soviet influence.

While the employees of Russia’s PMCs do not fall under official Russian control and are commonly referred to as mercenaries, they are not mercenaries in the true sense in that they are only allowed to operate to the benefit of Russian interests in operations approved by the Kremlin; any attempt to freelance in the traditional way of mercenaries would subject these soldiers to the severe penalties for “mercenarism” included in Russia’s criminal code. The PMCs also quietly receive logistical and transport support from the Russian Defense Ministry, though some Defense Ministry officials may resent the ability of the PMCs and their directors to enrich themselves through access to gas, oil and mineral wealth in the regions where they operate. Putin appears to be following the long-established Soviet practice of encouraging rivalries rather than cooperation amongst national security agencies and their proxies with the intention of preventing any one agency of becoming strong enough to overthrow the regime.

While the employees of Russia’s PMCs do not fall under official Russian control and are commonly referred to as mercenaries, they are not mercenaries in the true sense in that they are only allowed to operate to the benefit of Russian interests in operations approved by the Kremlin; any attempt to freelance in the traditional way of mercenaries would subject these soldiers to the severe penalties for “mercenarism” included in Russia’s criminal code. The PMCs also quietly receive logistical and transport support from the Russian Defense Ministry, though some Defense Ministry officials may resent the ability of the PMCs and their directors to enrich themselves through access to gas, oil and mineral wealth in the regions where they operate. Putin appears to be following the long-established Soviet practice of encouraging rivalries rather than cooperation amongst national security agencies and their proxies with the intention of preventing any one agency of becoming strong enough to overthrow the regime.

In many cases the PMCs now substitute for the usual work of civilian Russian intelligence agencies overseas, maintaining instead close relations with the GRU, the intelligence agency of Russia’s Ministry of Defense. GRU special forces were instrumental in seizing Crimea in 2014 and have been operating in the Donbas region since then.

The unexpected Russian demand for additional manpower in what was expected to be a brief and decisive operation in Ukraine is now draining personnel from the regions in which the PMCs operate. In some cases, these are not only Russians being pulled to the battlefields of Ukraine, but local fighters who have signed on to the PMCs as mercenaries and interpreters in Africa or Syria.

Elements of the Russian Wagner Group in Libya have been observed leaving for eastern Ukraine, with the remainder of the force locking down at Sirte, or further south at the Brak al-Shati military base and the Tamenhint airbase in Fezzan. Russian regulars are also reported to be leaving Abkhazia and South Ossetia for Ukraine, signs the Russian command is desperate for experienced troops to allow relief for frontline forces.

Syrians are now being recruited for mercenary service in Ukraine. Roughly 300 Syrians are undergoing advanced training in Russia, with the prospect of many more to follow. Most of the Syrian recruits are former members of Syria’s 25th Special Mission Forces Division, specialized in mechanized warfare using Russian equipment and accustomed to working closely with Russian Special Forces units. On March 11, President Putin authorized the recruitment of up to 16,000 volunteers from the Middle East.

OUTLOOK

Destroyed Russian T-8OU Main Battle Tank

Destroyed Russian T-8OU Main Battle Tank

Moscow’s agreement to postpone the invasion of Ukraine until the completion of the Beijing Olympics was a strategic mistake based on Russian assumptions that the war would be over in days. Frozen ground that might have allowed the off-road movement of armor and other military vehicles has now turned into the notorious Rasputitsa that bogged down German invaders 80 years ago. Hundreds of combat vehicles have been lost in the first five weeks of fighting to mud or Ukrainian attacks; according to Ukrainian intelligence, Russian authorities were dismayed to discover that “mothballed” replacements had been stripped of their valuable electronics and optical devices by their corrupt custodians.

Putin is reaching the end of his constitutional mandate as president. Unless he sends out firm signs that he plans on further constitutional manipulation to preserve his rule, failure in Ukraine, either real or perceived, may loosen his grip as new players seek to position themselves in a post-Putin struggle for power.

A Russian occupation of Ukraine seems impossible at the moment. The growing evidence of Russian war crimes in an unprovoked conflict will preclude the legitimacy of any Russian-backed Ukrainian government. Russian excesses could force a strongarm military occupation instead, tying up large numbers of troops with little chance of recruiting local “pro-Moscow” partisans to do the dirty work of occupation outside the Donbas region, at least in the short to medium-term. Concentrating nearly all of its effective troops in Ukraine leaves the rest of Russia’s enormous land-mass nearly defenseless and dependent on Russia’s nuclear option to deter incursions on its borders.

While adding conscripts to the invasion force mix may bring units up to strength, it cannot be reasonably thought that additions of poorly trained conscripts forced into frontline service will contribute in any meaningful way to combat effectiveness, and may even work against it. The use of foreign mercenaries in the “liberation” of Ukraine will only further diminish the Kremlin’s credibility and the legitimacy of its “special military operation.”

Parts of the Russian integrated military doctrine such as information manipulation and cyberstrikes have stuttered when called upon so far, having achieved far greater success in manipulating public opinion inside Russia than in the international arena, where its clumsy claims of “crisis actors” and insistence that Ukrainian troops are committing war crimes against Ukrainian civilians have found little resonance. If the regime in Moscow survives the war, it will be forced to address the structural problems of its military and the contribution these problems have made to the growing debacle in Ukraine. Whether this can be carried out effectively and honestly in a state where even mention of the word “invasion” is an offense is highly questionable.

NOTE

- The largely moribund Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) consists of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan. Georgia withdrew from the CIS due to Russian aggression in 2008; Ukraine withdrew for the same reason in 2018. Turkmenistan participates at a distance as an associate member.