Andrew McGregor

May 12, 1995

Introduction

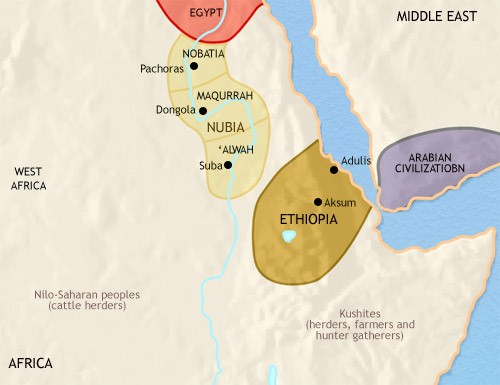

Parts of Nubia are a virtual open-air museum of mediaeval fortifications where successive generations and cultures have left samples of military architecture ranging from walled villages to imposing castles. Many of these works belong to the Islamic/Turkish period; most of the earlier Christian works were rebuilt or heavily modified in this era, adding to the difficulties of cultural identification. In this, the Muslims were only following the pattern set by the Christians, who had in their time rebuilt Pharaonic, Kushite, Meroitic and Roman structures.

Unfortunately, these important works have received scant attention from professional archaeologists. Proper surveys are rare and full-scale excavations almost unheard of. Our knowledge of many of these sites relies upon the observations of civil and military officials of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium who, with varying degrees of skill, attempted to date the ruins they came across on the basis of ceramic remains or brick-types. It is therefore entirely possible that upon closer investigation many of the sites identified in this paper may belong to other periods than those cited, and may likewise possess designs and features dissimilar to those described.

In examining the Christian sites, it is useful to keep in mind the various roles which the fortifications in Nubia could fulfill:

- Control of river-traffic

- Demarcation of political boundaries

- Refuge for local populations in times of attack or upheaval

- Housing for military and civil administrators

- Symbolic value as symbols of government prestige

- Customs house

- Storage of government taxes and revenues

- Internment of civil or political prisoners

This paper will examine the Christian sites by type of fortification:

1/ Walled settlements

2/ a) 2-storey houses; b) Blockhouses

3/ Re-used fortifications

4/ Forts/Castles of the Christian Kingdoms

a) Nobatia; b) Makuria; c) Alwa

Walled Settlements

The earliest of the Christian period walled settlements are notable for the strength of their walls and the apparent planning involved in their construction as fortified towns. This type is exclusively found in the northern extremes of Nubia, and its development is likely a response to the proximity of Egyptian military power and the raiding of regional nomads.

The sites, which include Kalabsha, Sabagura, Shaykh Da’ud and Ikhmindi, are characterized by large square or rectangular plans, enclosed by a massive stone wall equipped with bastions, corner towers and fortified gateways. [1] Stone and brick were both used in these defenses. [2]

The walled settlement in points further south is usually less elaborate, consisting of a dry stone wall that follows the terrain or the outline of a pre-existing village. Near Gemai a small settlement of 30 dwellings at Mugufil Island uses its position on a high bluff and a stone wall one meter in width for defence. [3] Close to the Second Cataract, in the Sarkamatto District, the village of Debba brought 70 houses together on a 20 meter high rock outcrop with dry stone walls. [4]

In the Dal district there are two major sites, Tiine and Sheeragi. [5] Tiine is a Late Christian settlement, built on a steeply rising island slope. The east side falls away in a sheer cliff. A semi-circular series of walls adapt to the contour of the hill, creating numerous small enclosures. The repetition of walls down the sloping face provided added defensive protection and a buffer against rock falling from higher levels of the site. Sheeragi also occupies a granite outcrop. Within a stone wall are dozens of houses and two larger works made of granite and schist, which may be the remains of a two-storey house.

South of the Second Cataract, on the island of Gergetti, a small community of 11 houses possessed a well-built double wall, the inner of rough stone and the outer of brick with a finished surface. The plan is in the form of an elongated hexagon, with bastions at the angles. The entrances were built with a zig-zag design and sloping ramps. [6] At Kitfogga (Ferka West), a fortified village uses the natural crest of the hilltop for the plan of its stone-walls. A church and smaller stone dwelling enclosures fill the interior. [7] At nearby Ferkinarti Island (also known as Diffinarti) is a walled village with possible traces of a two-storey house. [8]

Two-Storey Houses

The characteristics of the two-storey house have been clearly defined by Adams:

They are always two storeys high, square or nearly square in plan, and stoutly built; usually of mud-brick but occasionally with a mud brick supper storey resting on a stone-built lower storey. The ground-floor rooms are mostly blind cellars, accessible only from above, while the upper-storey rooms exhibit the typical arrangement of Christian Nubian living quarters. Rarely if ever is there an internal stairway connecting the upper and lower storeys. Many of the buildings lack any ground level access; they were reached originally by means of ladders leading to doorways a the level of the upper storey. [9]

From the evidence of ceramic remains and earlier levels of construction underneath the two-storey houses, it appears that these works are typically Late Christian, mostly of the 13th century. The two-storey house is common in the last Christian occupation phase of many settlements, and was often converted to other uses in the Islamic period.

The construction of sturdy two-storey buildings was made possible in Nubia through the use of brick vaulting, which was highly suitable for supporting upper stories of some weight. The walls are at least 80 cm. thick and are entirely constructed of brick, with the exception of several examples that use granite blocks in the lower courses. Doorways are present at the ground level, but these are in all cases but one post-Christian modifications.

Unique storage crypts are common to these structures, entered only through hatchways in the upper floor and often possessing their own brick vaulting. Secret crypts are often found cleverly concealed in the walls and other spaces of the building.

Most of the known two-storey houses can be found in the stretch of Nubia between Qasr Ibrim and Ferkinarti, though other examples can be found in the Letti Basin area. Some of the more notable examples of two-storey houses are found (from north to south) at:

Abkanarti One example on a rock-shelf, elevated over the village and outside its defensive walls. [10]

Kasanarti A late addition to the settlement and the village’s only apparent public building, the two-storey house at Kasanarti may have served as a combination watchtower and granary. [11] The structure is unusual, as it is joined on at least three side by contemporary structures. [12]

Gemai The two-storey house at Gemai is our lone example of such a structure with a ground-floor entrance and a stairway to the upper level. [13] Evidently the entrance was regarded as a mistake, for it was walled up at an early point in its occupation. [14]

Murshid West A number of two-storey mud-brick buildings are found here, amidst a town-site built on a rocky outcrop. In their lower storey they consist of typical vaulted chambers with hatchway entrances from the upper floor. [15]

Kulme (or Kulma) This site consists of three small, steep-sided islands in the Second Cataract, two of which bear two-storey houses. In earlier times the three islands may have formed a single site. In one of these well-preserved mud-brick structures a Greek inscription was found. [16]

Diffi Another fortified island site near Kulme. Here a series of two-storey houses on the tops of rocky outcrops face the main channel on the east. [17]

The purpose of the two-storey houses is not as clear as it might seem at first. Adams has noted a conspicuous lack of domestic evidence (mastaba-s, fireplaces, buried pots in the floor, etc.) and the absence of accumulated dwelling refuse [18] despite a clear similarity between the upper floor plan and the plan of contemporary Nubian houses.

Use as a communal storehouse or granary has been suggested [19], but again there is little evidence for such use of these buildings other than their suitability. Nevertheless, the design and popularity of these works suggests that they were intended to protect goods from attack and make access as difficult as possible for those unfamiliar with the design.

A curious feature is that the ratio of two-storey houses to settlement population size is widely inconsistent, with some tiny communities having a number of examples, while larger towns may only have one. This would seem to out-rule their use as civic buildings or feudal-style residences. While in continuous use as watchtowers, the two-storey house were probably reserved for emergency use by the community. The number of such structures may reflect the prosperity rather than the size of the community.

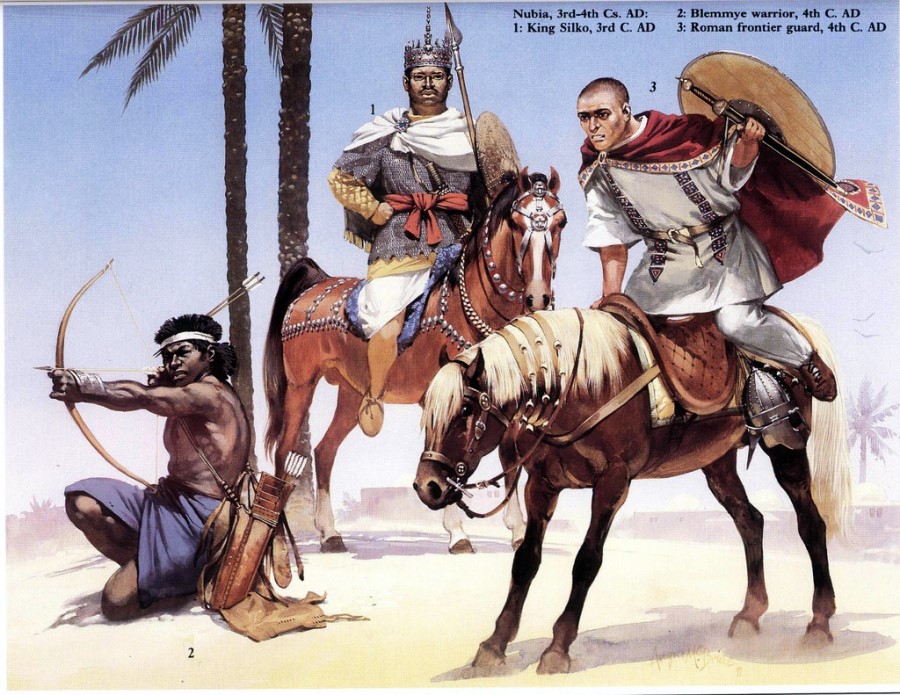

Warrior Types in Christian Nubia (Osprey)

Warrior Types in Christian Nubia (Osprey)

Blockhouses

The structures referred to here as “blockhouse” fortifications are not clearly distinct from the two-storey house, and are in most cases an elaboration of this basic structure.

The blockhouse of Meinarti is a larger version of the two-storey house and dates to the late Christian period (1200-1250 C.E.). [20] Potsherds are scarce on this site and the dating is reliant upon a painted Greek inscription. The blockhouse was built on the remains of an early monastery and served in part as a watchtower replacement for the monastery’s older tower. The building’s 15 room interior is labyrinthine, with some chambers accessible only through hatchways, or by crawling on one’s hands and knees. Adams, who excavated the site, emphasised the obvious defensive role of this structure with its metre-thick walls, and suggested a function as a community storehouse. [21] Most of the second storey was destroyed during this building’s use as a British gun emplacement in the Mahdiyya period. At Ushinarti is a very similar “blockhouse” with a labyrinth-type plan and secret chambers. [22]

Further south, in the Sai Island region, are a number of structures that outwardly resemble the Blockhouse-type, but lack the complex interior. These are found at Kayend [23], and on Nilwatti Island, where there are seven towers set out along the rock-crest. All have square plans and stone-and-brick construction. [24]

Re-Used Fortifications

Nubia was already an ancient land at the time the Christian kingdoms emerged and was wealthy in useful ruins, many of which were finely preserved. In many cases the Christians inherited fortified sites on hilltops from their military predecessors, such as at Jabal Adda and Qasr Ibrim, where Meroitic fortifications were re-used..

The Middle Kingdom fortress at Serra was re-occupied in late Christian times. Four churches and a pair of two-storey houses were built, but the ancient walls required only minor repairs. Askut was similarly occupied in the Late Christian period. The New Kingdom fortress at Jabal Sahaba was damaged byy wind erosion at the time of its early Christian occupation and was later built over by rough stone huts in the late Christian period, when a new stone wall was built round the plateau. [25]

Forts of the Christian Kingdoms

Kingdom of Nobatia

Jabal Adda: The Late Christian occupants of Jabal Adda relied mostly upon the Meroitic-era wall for defense, adding a new stone gate and making minor repairs. [26] The so-called “palace” may have had a defensive intent, as well as serving as a royal residence. Some of the ruins may represent a pair of two-storey houses. [27] The fortress was taken by the Mamluks in 1276 C.E.

Qasr Ibrim: This natural citadel had been fortified and later rebuilt by Taharqa (25th Dynasty), the Meroites and the Romans by the time the Christians re-occupied it and transformed Taharqa’s chapel into a Christian chapel. Three massive structures of the two-storey/blockhouse type were found here, but were removed by excavators without properly documenting the structures. [28]

Unlike most of the other forts of Nubia, we have historical evidence of Qasr Ibrim’s military role in the Christian era. An attack upon the castle in 957 C.E. was recorded by Yahya ibn Sa’id:

In that year the Kinig of Nubia came again up to Aswan and ravaged it. He killed and took prisoners. The armies of Egypt rushed against him by land and river. They killed and took prisoner, many of whom came from the Nuba [country]. Many others withdrew defeated and he [the King of Egypt] conquered their castle called Ibrim. [29]

In retaliation for a Nubian raid in 1172, an Ayyubid army under Shams al-Dawla Turan Shah laid siege to Ibrim, which fell after only three days. The town was laid waste and passed temporarily into Muslim hands.

Kulubnarti: The remaining ruins at Kulubnarti are those of a kourfa, an Islamic defensive work consisting of a dwelling, a courtyard and a strongly walled tower. [30] This complex seems to have expanded from a Late Christian two-storey house. [31] There are four other two-storey houses on the island. [32]

The Second Cataract: The defensive works of the Second Cataract region are alluded to by Salim al-Aswani (quoted by al-Maqrizi in his Khitat): “These mountains are the fortresses where the inhabitants of Maris take refuge.” [33] A large number of the villages here were fortified, the irregular shape of their walls indicating they were late additions. [34]

Significant Christian forts are found at Tanujur Island and Susinarti. The former is simple in plan, consisting of a dry stone wall around the peak of a small hill and mud=brick structures within. [35] Susinarti is far better built and designed – here a triangular wall faces onto the Nile in the south, the other two arms running up the side of the hill to a large tower-keep. Towers dominate the other two corners. Both of these forts rely unpn ceramic remains for their Christian period dating.

South of Dal, in the Kosha West district, is the Christian fort of Diffi, with a rectangular enclosure wall (80 x 40 cm.). Stone and brick are used in the construction. [36]

Kingdom of Makuria

Sai Island: This highly strategic island at the southern end of the Dal Cataract is the site of another constantly re-built fort, from Napatans through to the Turks. Vercoutter, the excavator, believes the fort may have been a very late Christian stronghold against the Arabs, [37] but points out that the late Christian dating relies upon its similarities to other Christian forts in the Nile Valley.

Khandak and Bakhit: Crawford suggests that the Fung-era fort at Khandak was built on the ruins of a Christian fort. A rough stone set of walls with semi-circular towers has been rebuilt with wall extensions and buttresses of unburnt brick. [38] A similar fort is at Bakhit, where 18 semi-circular towers are set at the corners and at regular intervals along the wall. [39] Lepsius identified Bakhit as a Christian site with a small church in the centre. The main walls are 30 feet thick and consist of rough stone on a core of unburnt mud-brick. The plan is rectangular and the whole site is covered with Christian potsherds.

Old Dongola: As capital of Makuria, Dongola was an extremely important Christian site, but not one possessed of natural defenses. As might be expected, it was necessary to respond with some innovative military architecture, a point driven home by the destructive Arab raid of 652 C.E., in which ‘Abdallah ibn Sa’d’s catapults destroyed the cathedral and most of the town. [40] a large amount of material from the “Church of Stone Pavement” appears to have found its way into the new defenses. [41] The implementation of the Baqt Treaty allowed the Christians time to construct an elaborate system of defenses, with a walled rampart near the river and bastions resting on a solid platform. [42] Semi-circular towers are spaced along the walls, mounted on granite foundations. The presence of many buildings outside the main walls may be explained by the existence of a series of outlying walls, as may have been described by Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadhani (c. 905 C.E.), who says Dongola possessed seven walls in his time. [43]

The defenses of Dongola were likely badly damaged in the Mamluk expeditions against King Dawud (1276 C.E.) and King Shenaun (1287, 1289 C.E.), [44] but were re-built in the post-Christian era. [45]

Al-Kab The two “castles” of al-Kab were first recorded in the 1820s by Caillaud and Linant de Bellefonds. The southern fort is a small post-Christian work, but the larger stone and brick structure to the north is one of a type of Christian fort that is also found at Bakhit and the Kubinat [46] (discussed below), and at Sai Island. [47] The mud-brick may have been a post-Christian restoration, but the entire work was in a ruinous condition by the early 19th century. [48] The plan is that of an irregular rectangle and features six semi-circular bastions. The rocky interior was filled with circular stone dwellings.

Kuweib The area around modern Abu Hamid has been of strategic importance since at least the time of the Egyptian New Kingdom. As the terminus for caravan routes from the north and west, it is unsurprising to find a Christian fort in the area. Kuweib was also situated on a small jabal in order to survey the northern channel of the Nile as it passes around Mograt Island. The dating of this site relies upon the many sherds and Christian-style graves found around the complex. [49]

This site has used all its natural advantages to create a strong defensive work – mud-brick walls are built around cores of granite boulders and the main wall itself is not continuous, but often detaches to strengthen natural features. There are no clear remains of bastions or buttresses. [50]

Al-Koro Al-Koro is south of Abu Hamid, on the east side of the Nile, near modern Kedata. Governor Jackson first noted these stone ruins, suggesting that they were a monastery with a church converted to a mosque. The plan of the fort is rectangular, with towers at the north-west and south-west corners. An inner enclosure is accessible only from the outer enclosure, where stone foundations and mud-brick walls indicate intensive occupation. The outer walls are of stone with a core of red-brick rubble. [51]

Gandeisi Gandeisi Island is mid-way between Abu Hamid and Atbara. The fort is small and irregularly rectangular, with towers at each corner and two additional bastions along the north-west wall. This wall is 17 feet thick and is along the riverside, the direction from which the defenders apparently expected an attack. The “L”-shaped entrance is on the inland side. Christian pottery is scattered across the area. [52]

Baqeir This site near Gandeisi remained unnoticed until Crawford found the foundation stones in 1951. Most of the plan was severely eroded, but it appears to have included bastions at each corner and one each on the longer walls, with a superstructure of mud-brick. The site is either that of a very small fort (35 x 20m) or a highly defended house. [53]

Al-‘Usheir About 20 miles south of Baqeir is a fort that resembles al-Koro in having an inner enclosure accessible only from a large outer enclosure. A third enclosure seems to be a late addition and has no apparent entry to either of the older enclosures.

In front of the south wall and the south-east gate are the remains of a lower rampart and fire-step outside the main wall, a defensive device known from the Middle Kingdom forts in Nubia. On the flat ground east of the castle is a chevaux-de-frise of pointed stones [54] designed to impede a rushing force of attackers. Bastions, curiously constructed in layers, are set at irregular intervals on the main wall. Around the inner enclosure are a parapet-wall and parapet in the places where the approach is not protected by the steep cliff on the north and east sides. This enclosure must have served as the castle-keep.

The architect of the al-‘Usheir fortress displays a knowledge of mediaeval fortifications as practised in Europe and the Near East, though certain fundamentals had been in place since the construction of the Middle Kingdom forts. The Christian dating is provided by the many inscribed sherds on the site.

Jabal Nakharu This fortress on the west side of the Nile, north of Atbara, was discovered by Crawford in 1951. It occupies a ridge of limestone that controls the narrow river-road below. The fort is square and built of dry-stone, probably with bastions in each corner and in the middle of each outer wall. Cross-walls run down from the plateau to the softer earth on the river’s edge and may have been equipped with gates to regulate traffic. [55]

The dating of Jabal Nakharu must be regarded as tentative. The ruinous condition prevents determining whether the bastions were semi-circular (as in Christian forts) or rectangular (as in post-Christian works). Red bricks are not in evidence at the site and the collection of painted sherds made by Crawford was subsequently lost.

Fourth Cataract (The Kubinat): At a strategic point where the Nile is only 170 metres wide there is a pair of forts situated on opposite banks. The walls of both forts run uphill from the river to the tops of rocky bluffs. Rock outcrops are incorporated into the defenses, which are otherwise built of dry stone with interior mud-mortar. The bastions are not bonded in and may be late additions. Strangely, the fort on the north bank has no less than ten entrances, but the broken ground round the fort makes visibility from the walls difficult, so that, according to Titherington, the number of gates “may commemorate a disaster when some of the garrison got surprised outside and jammed round an insufficient gate.” [56]

The Kubinat site is an enormous work in a highly barren area – each fort encloses an area of about three acres. The walls are ten feet thick and about 18 to 20 feet high. [57] The forts and their environs are covered with Christian and imported Roman pot-sherds. Typical Christian red-brick is present, as are earlier bricks of Meroitic type.

Kingdom of Alwa

Querri The kingdom of Alwa seems not to have relied upon great fortifications, although some of the fortresses previously described as Makurian may have been works of Alwa, depending on when and where political boundaries were drawn. A system of defenses is noticeably lacking at the capital of Soba. Distance from powerful external threats and a highly mobile army may have sufficed to preserve Alwan power until the Arab migrations into the region began.

Querri is located on Jabal Irau, overlooking the Sixth Cataract. The site is quite large, consisting of 12 hectares of dwellings and enclosures surrounded by massive walls of dry stone. Red brick and Christian wall-engravings are common at the site, as well as Islamic potsherds of the 15th and 16th centuries. [58]

The Arab penetration of Alwa met with little local resistance. [59] The Funj Chronicle describes the final defeat of the “kings of Soba and Querri” by Umara Dunqas in league with Abdallah of the Qawasma Arabs. The Abdallab Arabs preserve a tradition that the Christian survivors of the attack on Soba made a last stand at Querri, which Chittick described as the Sabaloka Gorge site in the Sixth Cataract. [60] The story and the interpretation are open to dispute:

Apart from the questionable authenticity of the site, however, the Funj Chronicle is far from explicit about the religion of Alwa at the time of its overthrow. The only mention of Christianity is in that part of the text which is taken from the much earlier account of Abu Selim. Since contact with Alexandria had been broken in the fourteenth century, it seems quite possible that Alwa might have passed under Moslem rule, unbeknown to the outside world, long before its final downfall. [61]

Conclusion

Most of the fortified Nubian sites dealt with in this paper belong to the Late Christian period, when external threats from the north endangered the existence of the Christian kingdoms. The traditional reaction of the Nubians to raids from the north was dispersal or concentration of the population. The proliferation of fortified sites may have seen the balance shift in favour of the latter strategy in Late Christian times, when the expiry of the Baqt Treaty renewed the northern threat.

The Muslim invasions had been highly destructive in 641 and 651-2 C.E., when the Christian kingdoms lacked effective defensive works. The invasion of Shams al-Dawla in 1172-73 C.E. and the seizure of Qasr Ibrim was a reminder of the necessity for strong defensive works. Jabal Adda and Qasr Ibrim became important sites of authority in the Late Christian period, able to offer refuge to the civil population in a crisis. Many of the settlements of the Classic Christian population in Lower Nubia show no signs of occupation after the 12th century [62], while Jabal Adda and Qasr Ibrim were the centers of an expanding population. The walled settlement of the early Christian period gave way to the two-storey building, which, despite its elusiveness of purpose, must have played a strong role as a watchtower, a secure place for the storage of goods and a temporary refuge for the local population. These towers were often a type of keep within a defensive wall, but there are cases of two-storey houses outside the town-walls.

A peculiar issue of the fortifications is the fact that so many of the watchtowers and defensive works were focused upstream [i.e. south], rather than towards the seemingly obvious threat from downstream Egypt. This suggests the Nubians’ most immediate security concerns were with populations or groups penetrating the kingdoms from other directions. The Nubian Christians desired control of the river trade and defenses against desert nomads. A strong defensive posture was not enough to deter the nomadic tribes, however:

The clashes which really and fatally exhausted Nubia were the raids on all, or a large part of, the Nile Valley, from the 10th century onwards. These were by nomads, coming from the deserts east and west of the Nile. Beja, Rabiah and Juhaynah attacked from the east; Luwatah, Zaghawa and other tribes from the west. [63]

The mobility of the Arab and African tribes precluded the old tactic of population dispersal and inspired a new form of defensive architecture that included the two-storey house/blockhouse in Lower Nubia. Further south in Makuria, especially upriver from Dongola, a more centralized means of defense evolved in which the resources of the state were devoted to the construction of massive forts rather than the small-scale community defenses of the north.

The Late Christian emphasis on military rather than religious architecture may reflect, if not an increasing secularization of Nubian culture, at least a weakening of its Christian component. As fortifications grew larger and more complex, the great churches and cathedrals were no longer being built, replaced by ever-shrinking and impoverished religious architecture. The fort/castle became the symbol of authority, meeting the urgent needs of the present, rather than those of the hereafter.

The role of feudalization in Late Christian society is uncertain; for example, did the two-storey houses belong to feudal lords or the community at large? What role did the defenses south to the 6th Cataract have in the governance or repression of the citizenry? Was command centralized or local? Were the commanders of defensive works of local origin or appointed by the King and his agents?

In the larger fortresses of the south we have no idea of the make-up or origin of the garrisons, or even if they had permanent garrisons at all. Some sites may have been intended as sanctuaries for the civil population, but would be largely ineffective without trained defenders capable of making sorties to secure supplies or disrupt offensive operations. Forts such as those of the Kubinat must have had permanent garrisons due to their isolated location, but the problem of supply must have been a difficult one.

The known history of the fortifications of Christian Nubia reveal that the most effective defense ever constructed by the Nubians was the Baqt Treaty negotiated with Egypt. At the time of its expiry, control of the Nile trade routes was rapidly diminishing in importance. The arrival of the Bani al-Kanz and their camel caravans brought an end to the prosperity of the Nile’s fortified customs houses as the caravans could set out from Egypt across unpatrolled desert routes, touching back upon the Nile wherever desired. The Mamluks, combining rapacity, ferocity and advanced military tactics, were more than a match for the Nubians. They penetrated the Christian defenses at will, taking Dongola in 1276 C.E. and again in 1289 C.E. Most telling is the record of the 33-day Mamluk pursuit of King Shenamun upriver from Dongola in which only Mamluk two soldiers died – one in combat while the other drowned. [64] Most effective of all, however, was the peaceful penetration of Christian Nubia by Muslims and their usurpation of the old inheritance system. Against this type of social transformation the great fortresses of Christian Nubia were helpless.

Notes

- W.Y. Adams: Nubia – Corridor to Africa (2nd ed.), Princeton N.J., 1984, p.493.

- P.F. Velo: “Les Fouilles de la Mission Espagnole à Cheikh Daoud,” in Fouilles en Nubie (1959-61), Cairo, 1963, p.28.

- A.J. Mills and H.A. Nordstrom: “The Archaeological Survey from Gemai to Dal – Preliminary Report on the Season 1964-65,” Kush 4, 1966, p.15.

- A. Vila: La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise), Fasc. 2, Les districts de Dal (rive gauche) et de Sarkamatto (rive droite), Paris, 1975, p.29.

- Ibid, pp. 49, 57.

- A. Vila: La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise), Fasc. 6 – Le district d’Attab, Est et Ouest, Paris, 1977, p.32.

- A. Vila: La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise), Fasc. 3 – District de Ferka (Est et Ouest), Paris, 1976, p.50.

- Ibid, p.90; W.Y. Adams: “Castle-Houses of Late Medieval Nubia,” Archéolgie du Nil Moyen, vol. 6, 1994, p.14.

- Ibid, p.11.

- Ibid, p.13.

- W.Y. Adams: “Sudan Antiquities Service Excavations in Nubia: Fourth Season, 1962-63,” Kush XII, 1964, p.222.

- Adams, op cit, 1994, p.13.

- Ibid, p.19.

- Ibid, p.13, fn.2.

- Mills and Nordstrom, op cit, 1966, p.14.

- Vila – Fasc. 2, op cit, 1975, p.62.

- Ibid, p.22.

- Adams, op cit, 1994, p.36

- Adams, op cit, 1964, p.222

- Ibid, p.225.

- Ibid, p.233.

- G. Donner: “Preliminary report on the Excavations of the Finnish Nubia Expedition 1964-65,” Kush 15, 1967-68, p.233.

- A. Vila: La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise), Fasc. 10 – Le District de Koyekka, Les districts de Morka et de Hamid – L’île Nilwatti, Paris, 1978, p.81.

- Ibid, p.104.

- T. Säve Söderbergh: “Preliminary Report of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition – Faras-Gemai, 1963-64, Kush 15, 1967-68, pp.235-37.

- N.B. Millet: “Gebel Adda Preliminary Report, 1965-66,” JARCE 6, 1967, p.62.

- Adams, op cit, 1994, p.13.

- Ibid, p.13.

- Vila – Fasc. 3, op cit, 1976, p.99

- W.Y. Adams: Kulubnarti I – The Architectural Remains, Lexington Kentucky, 1994, pp.81-83.

- Adams, op cit, 1984, p.518.

- Adams, op cit, 1994, p.14.

- The Excavations at Faras – A Contribution to the History of Christian Nubia, Bologna, 1970, p.113.

- Adams, op cit, 1984, p.513.

- “Antiquities of the Batn el Hajjar,” Kush 5, 1957, p.45.

- A. Vila: La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, aud Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise): Fasc. 4 – District de Mograkka (Est et Ouest); District de Kosha (Est et Ouest), Paris, 1976, p.101.

- J. Vercoutter: “Excavations at Sai, 1955-57 – A Preliminary Report,” Kush 6, 1958, pp.144-69.

- O.G.S. Crawford: The Funj Kingdom of Sennar, Gloucester England, 1951, p.37.

- Ibid, p.44.

- Y.F. Hasan: The Arabs and the Sudan, Edinburgh, 1967, p.20.

- Godlewski, op cit, 1991, p.109.

- Ibid, p.107.

- J. Vantini: Oriental Sources Concerning Nubia, Heidelberg, 1975, p.92.

- J. Vantini: Christianity in the Sudan, Bologna, 1981, p.92.

- Godlewski, op cit, 1991, p. 111.

- Crawford, op cit, 1951, p.44.

- Vercoutter, op cit, 1958, p.160, fn.72.

- Crawford, op cit, 1951, p.50.

- O.G. S. Crawford: Castles and Churches in the Middle Nile Region, SAS Occasional Papers, no.2, Khartoum, 1961, p.9.

- Ibid, p.9.

- ibid, pp.32-33.

- Ibid, pp.29-30.

- Ibid, p.30.

- Ibid, p.22.

- Ibid, p.18.

- G.W. Titherington: “The Kubinat – Old Forts in the Fourth Cataract,” Sudan Notes and Records 22, 1939, p.270.

- Ibid. p.269.

- Mohi el-Din Abdalla Zarroug, The Kingdom of Alwa, Calgary, 1991, p.62.

- Hasan, op cit, 1967, p.128.

- H.N. Chittick, “Antiquities of the Batn el Hajjar,” Kush 5, 1957, p.272.

- Adams, op cit, 1984, p.539.

- Adams, op cit, 1984, p.511.

- Vantini, op cit, 1970, p.267.

- Hasan, op cit, 1976, p.115.

Bibliography

Adams, William Y. : “Sudan Antiquities Service Excavations in Nubia: Fourth Season, 1962-63,” Kush XII, 1964, pp.216-47.

Nubia – Corridor to Africa (2nd ed.), Princeton N.J., 1984.

“Castle-Houses of Late Mediaeval Nubia,” Archéolgie du Nil Moyen 6, 1994, pp.11-45.

Kulubnarti I – The Architectural Remains, Lexington Kentucky, 1994.

Chittick, H.N.: “Antiquities of the Batn el Hajjar,” Kush 5, 1957, pp. 42-48.

Crawford, O.G.S.: The Funj Kingdom of Sennar, Gloucester England, 1951.

Castles and Churches in the Middle Nile Region, SAS Occasional Papers, no.2, Khartoum, 1961.

Donner, Gustaf : “Preliminary report on the Excavations of the Finnish Nubia Expedition 1964-65,” Kush 15, 1967-68, pp.70-78.

Godlewski, Wlodimierz: “The Fortifications of Old Dongola – Report on the 1990 Season,” Archéolgie du Nil Moyen 5, 1991, pp.103-28.

Hasan, Y.F.:The Arabs and the Sudan, Edinburgh, 1967

Jakobielski, Stefan: “North and South in Christian Nubian Culture – Archaeology and History,” in T. Haag (ed.): Nubian Culture Past and Present, Stockholm, 1987, pp.231-35.

Knudstad, J.: “Serra East and Doginarti,” Kush 14, 1966, pp.165-86.

Millet, Nicholas B.: “Gebel Adda Preliminary Report, 1965-66,” JARCE 6, 1967, pp.53-63.

Mills, A.J.: “The Reconnaissance Survey from Gemai to Dal – A Preliminary Report,” Kush 13, 1965, pp.1-12.

“The Archaeological Survey from Gemai to Dal – Report on the 1965-66 Season,” Kush 15, 1973, pp. 200-210.

Mills, A.J. and H.A. Nordstrom: “The Archaeological Survey from Gemai to Dal – Preliminary Report on the Season 1964-65,” Kush 4, 1966, pp.1-15.

Monneret de Villard, Ugo: La Nubia Romana, Rome, 1941.

La Nubia Mediovale (2 vol.s), Cairo, 1935.

Plumley, J. Martin: “The Christian Period in Nubia as Represented on the Site of Qasr Ibrim,” in P. Van Moorsel (ed.): New Discoveries in Nubia, Leiden, 1982, pp.99-110.

Säve Söderbergh, T.: “Preliminary Report of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition – Archaeological Invesstigations between Faras and Gemai, November 1963 – March 1964,” Kush 15, 1967-68, pp.211-250.

Shinnie, Peter L.: “The University of Ghana Excavations at Debeira West, 1964,” Kush 13, 1965, pp.190-94.

Titherington, G.W.: “The Kubinat – Old Forts in the Fourth Cataract,” Sudan Notes and Records 22, 1939, pp.269-71.

Vantini, John: The Excavations at Faras – A Contribution to the History of Christian Nubia, Bologna, 1970.

Oriental Sources Concerning Nubia, Heidelberg, 1975.

Christianity in the Sudan, Bologna, 1981.

Velo, F. Presedo: “Les Fouilles de la Mission Espagnole à cheikh Daoud,” in Fouilles en Nubie (1959-61), Cairo, 1963.

La Fortaleza Nubia de Cheikh-Daud-Tumas (Egipto), Madrid, 1964

Vercoutter, J.: “Excavations at Sai, 1955-57 – A Preliminary Report,” Kush 6, 1958, pp.144-69.

Vila, André: La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, aud Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise):

Fasc. 2 Les districts de Daol (rive gauche) et de Sarkamatto (rive droite), Paris 1975

Fasc. 3 District de Ferka (Est et Ouest), Paris, 1976

Fasc. 4 District de Mograkka (Est et Ouest); District de Kosha (Est et Ouest), Paris, 1976

Fasc. 6 Le district d’Attab, Est et Ouest, Paris, 1977

Fasc. 9 L’Ile d’Arnyatta, Le District d’Abri (est et Ouest); Le district de Tabaj (Est et Ouest), Paris 1978

Fasc. 10 Le district de Koyekka (rive droite); Les districts de Morka et de Hamid (rive gauche); L’Ile Nilwatti, Paris, 1978

Zarroug, Mohi el-Din Abdalla: The Kingdom of Alwa, Calgary, 1991