Andrew McGregor

January 26, 2016

“There is no future for ISIS. Not in war and not in peace.” These words were spoken not by Barack Obama or Vladimir Putin, but rather by Hezbollah leader Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, whose Lebanese Shi’a supporters are engaged in a growing battle against the Sunni militants inside Syria (Press TV [Tehran], November 14, 2015). Despite this, few analysts have considered how Hezbollah’s commitment to defeat Sunni extremists in Syria would fit into a larger Western and/or Russian-directed military intervention to destroy the Islamic State terrorists, especially when the movement is itself considered a terrorist organization by many Western states.

Hezbollah Patrol in Syria

Hezbollah Patrol in Syria

Nasrallah insists his movement is conducting pre-emptive military operations designed at preventing Sunni extremists from entering Lebanon, but many Lebanese (including some Shi’a) accuse Hezbollah of drawing the terrorists’ attention to Lebanese targets by acting at the command of the movement’s Iranian sponsors (Reuters, September 6, 2013; Jerusalem Post, September 6, 2013) .

Hezbollah (“the Party of God”) addresses these accusations in two ways: by stating that the Syrian intervention is intended to defend all Lebanese, and by describing the Islamic State and al-Qaeda affiliated al-Nusra Front as tools Israel uses to destroy regional opposition, thus bringing the intervention within the larger anti-Israel “Resistance” agenda that has formed the movement’s core ethos since its formation (Reuters, August 15, 2014).

Hezbollah is correct in one sense; Lebanon and its delicate ethnic and religious balance will indeed be in the Islamic State organization’s gun-sights if it succeeds in establishing a secure base in neighboring Syria. Nonetheless, since joining the war in 2013, Hezbollah has lost lives, resources, and most of the moral authority it once commanded even in Sunni communities in the Middle East after repelling an Israeli incursion into southern Lebanon in 2006.

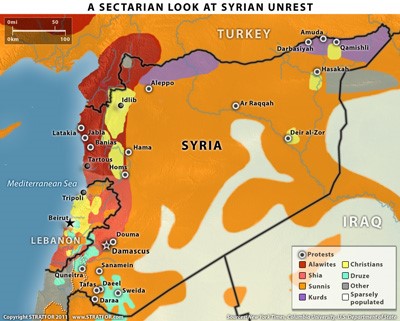

There was relatively little in the way of confrontation between Hezbollah and the Islamic State organization for some time as Hezbollah tended to operate mainly in western Syria while the Islamic State is strongest in the more lightly populated east. This all changed when the Islamic State took the war to Hezbollah on November 12, 2014 by deploying a pair of suicide bombers against the Burj al-Barajneh district of southern Beirut, a mixed but largely Shi’a neighborhood where Hezbollah has a strong presence, killing and wounding scores of civilians. Eager to punish Hezbollah for its Syrian intervention, the Islamic State promised “the Party of Satan” much more of the same (al-Manar TV, November 12, 2015).

On December 3 2015, US Secretary of State John Kerry admitted that the Islamic State cannot be defeated without ground forces, but suggested these should be “Syrian and Arab” rather than Western in origin (Reuters, December 23, 2015). Washington’s efforts so far to assemble and train a politically and religiously “moderate” rebel army have been “a devastating failure” according to Nasrallah, who insists that air strikes alone will do nothing to eliminate the Islamic State organization (AP, September 25, 2015).

Who, then, should these ground fighters be? They will certainly not be British Prime Minister David Cameron’s mythical 70,000 “moderate” rebels (Independent, December 1, 2015). Saudi Arabia and the Gulf nations regard American-led efforts to restore order in Syria as ineffective and are unlikely partners in a Western-led military initiative; besides, their own resources are currently committed to the ongoing military struggle for Yemen. Syria’s Kurdish militias are capable, but have displayed little interest in campaigning outside their own traditional territories. This leaves regime forces and their allies as the only local groups currently capable of tackling the Islamic State in the field.

Saudi Arabia’s clumsy attempt to create a Saudi-led anti-terrorist military alliance of 34 Islamic nations – mainly by announcing its existence to the surprise of many nations the Kingdom claimed were members – further escalated tensions between Shiite and Sunni communities when it was observed that majority Shi’a nations like Iraq and Iran were noticeably absent from the list of members.

Though Lebanon’s Sunni prime minister Tammam Salam declared Lebanon was part of the alliance, membership was immediately rejected by Hezbollah and most Lebanese Christian parties, the latter correctly pointing out that Lebanon had no status as an “Islamic nation.” A Hezbollah statement claimed the Saudis were unsuitable as leaders of an anti-terrorist coalition as they were involved in state terrorism in Yemen and supported terrorist organizations there as well as in Syria and Iraq. The statement went on to question whether the new alliance would confront “Israeli terrorism” or instead target “the Resistance” (Hezbollah, Iran and Syria) (Al-Manar, December 17, 2015; AP, December 17, 2015). Salam claims to have since received assurances from the Kingdom that the Islamic State and not Hezbollah will be targeted, but vital questions remain concerning how the Sunni alliance would interact with Hezbollah and other Shiite forces on the Syrian battlefield (Daily Star [Beirut] Dec 16 2015). Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to execute Shaykh Nimr al-Nimr, a leading Shiite opposition leader, will only embitter the struggle between Shiites and Sunnis in Syria – Nasrallah described it as “an appalling event” (Reuters, January 3, 2016).

Hezbollah Fighter in Action against Free Syrian Army (AP)

With growing calls for greater Western military intervention in Syria and even to set aside the anti-Assad rebellion in order to allow the Syrian Army to focus on the elimination of the Islamic State, it must be understood that at this point of the war there is no functioning Syrian Army that can be separated and deployed independently of Hezbollah and the Iranian military advisers now running Syrian Army operations.

With few exceptions, Syria’s war does not unfold in a series of set-piece battles, but rather in small actions, “a battle of ambushes, of surprise attacks” as one rebel colonel described it (Reuters, October 30, 2015). This daily war of attrition and a rash of desertions has greatly reduced the size and effectiveness of the Syrian national army. Now most operations are planned by Iranian and Hezbollah advisors using well-trained Hezbollah fighters to stiffen Syrian units in the field.

Hezbollah now has an estimated 6000 fighters in Syria, mostly experienced light infantry well-suited to the war’s pattern of small-level clashes punctuated by the occasional major battle. While losses have been heavy at times, the deployment has given Hezbollah valuable battlefield experience in operating on unfamiliar terrain and in cooperation with the regular forces of other nations (Syria, Iran and Russia).

Hezbollah’s war aims are both declared (protecting Shi’a shrines in Syria) and undeclared, the latter including keeping supply lines from Iran open, preserving the friendly Assad regime and keeping Sunni extremists (al-Nusra, Islamic State, etc.) from entering Lebanon. To mollify those who claim the Syrian adventure has little to do with the anti-Israel “Resistance” agenda, Nasrallah claims that Zionists and Sunni extremists have the same goal – “destroying our peoples and our societies” (AFP, October 18, 2015). The Hezbollah leader also insists that any political solution in Syria “begins and ends” with President Bashar al-Assad (AFP, June 6, 2014).

Though Hezbollah has a polarizing effect on Lebanese politics and a record of terrorist attacks, the movement, unlike the Islamic State organization, is no wild-eyed band of religious fanatics ready to slaughter everyone that does not share their religious preferences. As a political party with a strong social-welfare arm, Hezbollah’s leaders have deftly created a political alliance with Maronite Christian factions, secular Druze and even Shi’a of the Amal Movement with whom Hezbollah waged a bitter war in the 1980s.Lebanese sources indicate that Hezbollah began recruiting Christians, Druze and Sunnis for the fight against the Islamic State in late 2014 (Daily Star [Beirut], November 12, 2014). Nonetheless, opposition to Hezbollah within Lebanon cannot be understated.

To counter the political “normalization” of the movement, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has proclaimed Hezbollah a global threat that has organized, with Iran, a terrorist network spanning 30 countries on five continents (AFP, July 28, 2015). Nasrallah, in turn, has emphasized the “ISIS monster’s” threat to Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, some of them important sources for private donations to the Islamic State and other Sunni extremist groups. According to Nasrallah: “This danger does not recognize Shiites, Sunnis, Muslims, Christians or Druze or Yazidis or Arabs or Kurds” (Reuters, August 15, 2015). Jews are notably absent from the Hezbollah leader’s list of ethnicities under threat as Hezbollah considers Israel’s Jews to be in league with the Islamic State terrorists.

Last month, President Netanyahu abandoned Israel’s traditional policy of refusing to confirm or deny involvement in foreign air-strikes, acknowledging that Israel was targeting Hezbollah arms shipments to prevent the transfer of “game-changing” weapons from Syria to Lebanon. When Israel believes it has missed a weapons transfer, it attacks Syrian arms stocks, inhibiting the Syrian Army’s ability to combat the Islamic State and other rebel groups (DefenceNews, November 18, 2015). Israeli airstrikes have not targeted Islamic State forces or installations in Syria; like al-Qaeda, ISIS appears reluctant to attack Israel directly, insisting that America must first be weakened and an Islamic state established in Iraq and Syria before Israel can be addressed (Arutz Sheva 7, October 7, 2014).

This reluctance to strike Israel only reinforces Hezbollah’s belief that there is cooperation between Israel and the Sunni extremists (Tasnim News Agency [Tehran], December 10, 2015). Bashar Assad himself has joked that no one can say al-Qaeda doesn’t have an air force when they have the Israeli Air Force to attack regime and Hezbollah positions (Foreign Affairs, January 25, 2015).

Last summer, Hezbollah and Syrian government forces succeeded in driving rebel forces from their last positions in the Qalamun region alongside the border with Lebanon after nearly two years of fighting. Islamic State and al-Nusra fighters had used the region for attacks within Lebanon. Since then, Hezbollah has intensified its war against the Islamic State and Assad’s other enemies in coordination with Russian airstrikes. Though initially criticized for focusing on Syrian Turkmen communities and American-supported units of the Free Syrian Army, Russia has expanded its target list to include the Islamic State, the Nusra Front and the Jaysh al-Islam militia.

So far, Russia appears to be tolerating Israeli strikes on Hezbollah targets, but has also been accused by Israeli military sources of supplying anti-ship cruise missiles to Hezbollah, whether directly or indirectly through Syrian middlemen (al-Manar TV [Beirut], January 15; Jerusalem Post, January 14). Moscow’s deployment of powerful S-400 ground-to-air missiles in Syria means Russian objections to specific air operations over Syria will have to be taken seriously. Russia and Israel have made extraordinary efforts to avoid running in to each other in Syrian airspace – the consequences of an accidental clash could be significant; a Russian military alliance with the “Resistance Axis” of Hezbollah, Syria and Iran would change the strategic situation of the Middle East. Russia has indicated it considers Hezbollah to be a “legitimate socio-political force” rather than a terrorist group, suggesting it is prepared to work with the group in Syria (Reuters, November 15, 2015).

Regardless of the number of “moderate” rebels in Syria, Hezbollah remains better trained, better armed and better led. The moderates cannot operate effectively against the Islamic State until and unless they can disengage from their conflict with the Syrian Army and the rest of the “Resistance Axis.” The West’s contradictory war aims in Syria have been noted by former UK chief of defense staff General David Richards, who suggests that the anti-Assad rebellion needs to be set aside in order to allow the Syrian Army, Hezbollah and their Iranian backers to focus on the elimination of the Islamic State (Guardian, November 18, 2015). However, this plan would require somehow persuading anti-Assad factions to abandon or postpone their struggle as well as cooperation with anti-Assad Kurdish forces to be successful, not to mention a degree of political flexibility in the Western allies that does not exist at present.

So what are the West’s options? Hezbollah might be persuaded to leave Syria if it was guaranteed that capable military forces (preferably not Western in Hezbollah’s view) would serve as their replacement in the defense of the Assad regime. There is little political appetite for this proposition in the West at the moment, despite an increasing number of voices suggesting that the Islamic State organization rather than Assad might be the most pressing problem in Syria.

An alternative is to try to find a means of combating the Islamic State on the ground without recognizing or coordinating with Assad/Hezbollah forces engaged in the same battle, a tricky bit of military manoeuvering that is likely to end badly.

A third option would be to confront Assad regime/Hezbollah/Iranian forces simultaneously with attacks on the Islamic State to create a “New Syria,” a move that would run a high risk of confrontation with Russia and Iran, incite international opposition and the expansion of the conflict well beyond Syria’s borders. The resulting power vacuum in the ruins of Syria would be worse than that experienced in Libya and would in the end pose a direct security threat to both the West and the Middle East.

To resolve the Syrian crisis it is essential either to come to terms with Hezbollah or to confront it, knowing in the latter case that the bulk of the movement and its leadership will remain in Lebanon with the means to strike back at its international antagonists. Ignoring its existence or its role in confronting anti-Shi’a Sunni extremist groups like the Islamic State will not be an option in any ground-based effort to crush Islamic State terrorists.

This article first appeared in the January 26, 2016 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor