Andrew McGregor

December 15, 2004

With Russia once again threatening pre-emptive strikes on “terrorist” installations in Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge, it seems timely to re-examine the alleged activities of Jordanian terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in the region several years ago. The Pankisi Gorge is a river valley about 34 km long in north-eastern Georgia. It is home to about 10,000 Kists, belonging to the same ethnic group as the Chechens and Ingush. After the outbreak of the second Russo-Chechen war in 1999, eight thousand Chechen refugees joined the Kists there. Arriving later were Chechen field commander Ruslan Gelayev and the survivors of the Battle of Komsomolskoye (site of a major Chechen defeat). Gelayev chose to rebuild his forces in the Pankisi Gorge; with Georgia engaged in a struggle with Russia over the breakaway provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia there was little danger of extradition.

By 2002, unsubstantiated reports began to emerge of al-Qaeda leaders taking refuge in the Gorge after the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan. Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov even suggested Bin Laden himself might be in the Pankisi Gorge. [1] Russia wished to focus international attention on the Gorge, where Gelayev had built up a significant armed force of 800 Chechens, together with about 80 international mujahideen, mostly Turks and Arabs. Georgian authorities pretended to be ignorant of their presence, despite having negotiated a deal to supply and arm Gelayev’s force in return for a little extra-curricular combat on behalf of Georgia in Abkhazia in 2001.

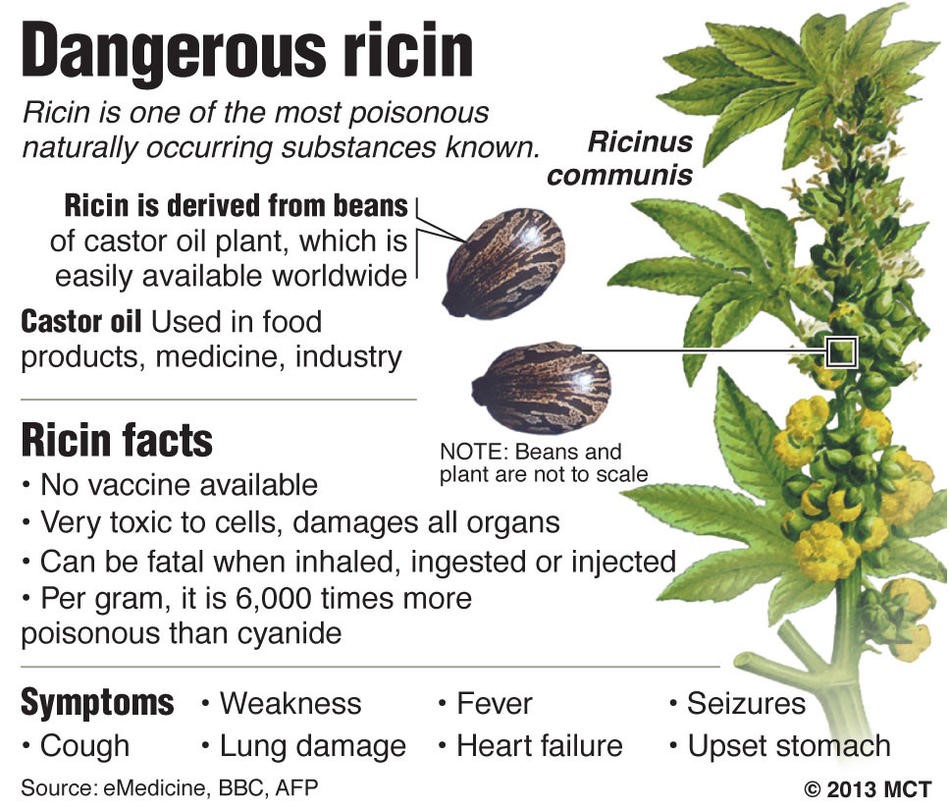

In his pre-Iraq invasion address to the United Nations Security Council Secretary of State Colin Powell declared that “we know that Zarqawi’s colleagues have been active in the Pankisi Gorge, Georgia, and in Chechnya, Russia. The plotting to which they are linked is not mere chatter. Members of Zarqawi’s network said their goal was to kill Russians with toxins.” Powell emphasized the production of ricin as a major threat, and the importance of Zarqawi as a master poisoner. Abu Atiya (Adnan Muhammad Sadik) was named by Powell as the leader of al-Qaeda’s Pankisi operations and part of Zarqawi’s network. In July 2002, there were reports that the CIA had warned Turkish officials that Abu Atiya had sent chemical or biological materials to Turkey for use in terrorist attacks.

Georgian raids started in February 2002, while the main security “crackdown” in Pankisi was carefully timed to follow the September 2002 departure of Gelayev’s forces for Russian territory. At the end of the security sweep in October, fifteen minor Arab militants were turned over to the U.S. The operation marked the first deployment of Georgian graduates of the Train and Equip program, a U.S. initiative to train a core professional army for Georgia. No evidence of chemical labs was discovered, though Georgia cautiously conceded that some militants in the Pankisi Gorge “may” have been chemical weapons experts.

The Ricin Crisis

There seems little reason for Zarqawi to move to the Pankisi Gorge, which makes a useful base for striking into Chechnya but is remote from Middle Eastern operational environments. The languages in the region are unfamiliar to most Arabs and the militants in Pankisi under the command of Ruslan Gelayev were nearly all bound for Chechnya. Gelayev feuded constantly with Islamist commanders in the Chechen resistance, and would be unlikely to have taken orders from Arab Islamists. Indeed, the entire story conflicts with the usual account of Zarqawi being wounded in Afghanistan and receiving medical treatment in Baghdad before joining Ansar al-Islam in the north.

In the buildup to the Iraqi war in early 2003, dozens of North Africans (mainly Algerians) were arrested in Britain, France and Spain on charges of preparing ricin and other chemical weapons. Colin Powell and others trumpeted the arrests as proof of the threat posed by the Zarqawi-Chechen-Pankisi ricin network (which had now been expanded to include the Ansar al-Islam of Kurdish northern Iraq).

In the buildup to the Iraqi war in early 2003, dozens of North Africans (mainly Algerians) were arrested in Britain, France and Spain on charges of preparing ricin and other chemical weapons. Colin Powell and others trumpeted the arrests as proof of the threat posed by the Zarqawi-Chechen-Pankisi ricin network (which had now been expanded to include the Ansar al-Islam of Kurdish northern Iraq).

French and British security officials were astounded by Powell’s insistence on February 12, 2003, that “the ricin that is bouncing around Europe now originated in Iraq.” With the Iraq invasion only weeks away, the source of the ricin threat moved from Georgia to Iraq. In the UK charges were dropped when government laboratories could find no trace of the poison in seized material. In Spain all the suspects were released when the poisons turned out to be bleach and detergent. In France, ricin samples were revealed to be barley and wheat germ. [2]

Responding to the arrests in Britain and France, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov stated that the suspects had been trained in Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge, where al-Qaeda laboratories were manufacturing ricin. Few bothered to question why anyone would set up a ricin lab requiring large numbers of castor beans for the production of even a tiny amount of purified ricin in a region with no native castor plants.

The “Chechen Network”

French Judge Jean-Louis Brugiere (a leading anti-terrorism official) led the attack against what came to be known as the “Chechen network” declaring that “the Chechens are experts in chemical warfare. And Chechnya is closer to Europe than Afghanistan.” The “Chechen network” was curiously devoid of Chechens: nearly all the suspects were Algerian. Despite the outcome of the European cases, the myth of the ricin-producing “Chechen network” took hold.

Chechen Brigadier General Rizvan Chitigov is the only Chechen leader who appears to have taken an interest in chemical weapons, and is frequently accused by the FSB of planning chemical operations against Russian troops. In 2001, leading FSB officials cited “serious grounds for suspecting him to be a CIA agent.” [3] Last October, Chechen police discovered two kilograms of mercury, which they claimed Chitigov intended to use to poison a water intake facility.

By August 2002 reports were emerging that Ansar al-Islam were experimenting on animals with aerosolized ricin under Zarqawi’s direction. Aerosolization is the only method of delivering lethal doses of ricin to large numbers of people, but requires a great deal of specialized equipment and expertise, certainly far beyond the limitations of a primitive lab. Ricin cannot be absorbed through the skin and was abruptly dropped from most state weapons programs as soon as the more lethal Sarin nerve gas was developed. Despite its potency, no effective method has yet been devised for the mass distribution of ricin. The weaponization of ricin is sufficiently complex that it almost precludes such use by non-state parties.

Conclusion

There is no evidence that Zarqawi knows anything about the manufacture or deployment of chemical and biological weapons. In the aftermath of the Jordan bombing attempt in April, Zarqawi made his only known statement on the use of chemical weapons, posted on alminbar.front.ru: “If we had such a bomb – and we ask God that we have such a bomb soon – we would not hesitate for a moment to strike Israeli towns.” [4]

Jordan’s King Abdullah II referred to Zarqawi as a “street thug” last July, adding that the media had inflated Zarqawi’s intelligence and skills to create a larger threat. Jordanian security services claimed the attempted attack was a chemical assault using nerve gas and blister agents, capable of killing 80,000 people. No evidence was presented, and even Zarqawi refuted the use of chemical agents in the plot. [5] Zarqawi’s career has followed the path of high-school dropout, failed video retailer, prisoner and gunman. It is thus impossible to identify how or when Zarqawi became an expert in chemistry.

The identification of a ricin-producing “Chechen network” under Zarqawi’s control developed because it was useful. In the media, every unproven allegation “from un-named intelligence sources” was treated as unquestionable evidence, each being used as proof of the last. This house of cards was saluted by Britain, Russia, the U.S. and eventually even the Georgians as it served to advance the interests of each. The British government was trying to justify an unpopular decision to join the Iraq war, and Russia was able to implicate Georgia in a Chechen-al-Qaeda network of terror, invoking “the common cause” of the anti-terror coalition in support of their methods in Chechnya. The U.S. trained Georgian troops essential for the protection of the two new oil pipelines about to cross Georgia under the cloak of counter-terrorist assistance, while using the Zarqawi chemical threat to drum up support in the United Nations. [6]

Last month Russia claimed that Abu Atiya (together with Abu Hafs “Amjet” and Abu Rabiya) commanded 200 Chechens and 30 Turkish “mercenaries” in Pankisi, though there is no explanation of how Abu Atiya, who was arrested in Azerbaijan in September 2003, has returned to action. [7] Georgia continues to deny the presence of any Chechen or Arab militants in the Gorge, calling Russian statements “a provocation.” Meanwhile Abu Musab al-Zarqawi remains central to the disinformation campaigns that obscure our understanding of Islamist terrorism.

Notes:

- “FM: Bin Laden could be in Caucasus”, Associated Press, Feb. 17, 2002.

- “The strange case of the dangerous detergent” New Statesman, April 14, 2003, By Justin Webster, “Ricin scare in Paris is false alarm,” AP, April 11, 2003.

- Russian Public TV (ORT), Interview with Nicolai Patrushev and Aleksandr Zdanovich, April 18, 2001 (BBC Monitoring, April 19, 2001).

- Translation from “‘Zarqawi tape’ says non-chemical attack planned on Jordanian intelligence”, AFP, April 30, 2004.

- “Al-Zarqawi denies the Jordanian version over the chemical attack”, Arab News, May 1, 2004.

- Baku-Tbilisi-Supsa and Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan.

- Not to be confused with the late Abu Hafs al-Misri or Abu Hafs ‘the Mauritanian’.

This article was first published in the December 15, 2004 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.