Andrew McGregor

Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(6)

Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC

June 25, 2024

Executive Summary:

- Mahamat Idriss Déby, Chad’s new president, has voiced interest in increasing cooperation with Moscow amid creeping Russian influence throughout the Sahel.

- Any move by the young president toward replacing French influence with a Russian presence will likely be met with strong resistance from Chad’s military leaders, who have not expressed a preference for Russia.

- Suspicions that Russian troops have already entered the country may have been misplaced, as the troops arriving in April were an official Hungarian contingent with no clear connections to the Kremlin.

Mahamat Idriss Déby and Vladimir Putin (Kremlin.ru)

Mahamat Idriss Déby and Vladimir Putin (Kremlin.ru)

Surrounded by countries with a growing Russian presence, Chad’s new president, Mahamat Idriss Déby, appears to be entertaining Moscow’s overtures at the expense of long-established ties to former colonial power, France. The question is whether Chad is merely diversifying its partners or moving directly into the Kremlin’s orbit. Much has changed since 2021, when then-Foreign Minister Chérif Mahamat Zene said the presence of Russian mercenaries in Africa posed “a very serious problem for the stability and security of my country” (France24/AFP, September 24, 2021). More recently, during a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in January in Moscow, Déby remarked, “This is a history-making visit. Chad and Russia maintain long-time relations. … We hope that this visit will allow us to enhance our bilateral relations and to strengthen our relations” (Kremlin.ru, January 24).

Chad’s Military: In the French Tradition (NYT)

Chad’s Military: In the French Tradition (NYT)

The French military helped drive the Soviet-supported Libyans out of Chad during the Toyota War in 1987. French forces then intervened to preserve the rule of Mahamat’s father, Idriss Déby Itno, in 2006, 2008, and 2019. Even the 2021 rebel offensive, in which Idriss was killed after ruling Chad for 30 years, was repulsed with the help of French aerial and satellite intelligence (AFP, March 15).

Chad’s relations with France deteriorated quickly after Mahamat became the country’s transitional ruler on April 20, 2021, heading a junta of 15 generals. France sought quick elections, while Mahamat insisted on an 18-month transition that eventually stretched out to three years before he was elected president in May. The Russian Foreign Ministry expressed satisfaction with the “final stage of the transition process” and a desire to strengthen relations with Chad (TASS, May 11).

General Ahmet Kogri (TchadOne)

General Ahmet Kogri (TchadOne)

Franco-Chadian General Ahmet Kogri (aka Serge Pinault), director of Chad’s internal security agency, l’Agence Nationale de Sécurité de l’Etat (ANSE), was accused of playing a leading role in repression of the 2022 demonstrations. The protests opposed the extension of the transitional period through a special unit tasked with the interrogation, torture, and eventual murder of demonstrators in N’Djamena, Chad’s capital (TchadOne, January 3). Kogri was replaced in February, a move that has been interpreted as part of a separation from French influence and a means of bringing the ANSE under tight presidential control (TchadInfos, February 21; Jeune Afrique, February 22). The French military still has three bases in Chad, with roughly 1,000 troops.

General Amine Idriss (al-Wihda)

General Amine Idriss (al-Wihda)

The US presence in Chad has also been compromised in recent months. In April, French-trained General Amine Idriss, Chadian Air Force chief of staff, ordered the immediate suspension of US activities at the Adji Kosseï air base, citing Washington’s inability to justify its continued presence there (Al-Wihda, April 25). On May 1, 75 members of the US 20th Special Forces Group withdrew from Chad to Germany.

Initially, the order was thought to be related to pre-election tensions between the United States and Mahamat over alleged US support for the leading opposition candidate. Some sources suggested, however, that the move was intended to force a new, more profitable deal involving Washington’s rental of the air base (TchadOne, April 20). Others argued that France was behind the Chadian demand based on worries that US troops withdrawing from neighboring Niger might end up in N’Djamena (Al-Wihda, April 25). On June 10, some 1,100 US troops in Niger began their withdrawal (see EDM, April 11).

Chadian President Mahamat Idriss Déby (Sputnik)

Chadian President Mahamat Idriss Déby (Sputnik)

Only days before the presidential elections, a report described the arrival of 130 Russian troops at the N’Djamena airport. The soldiers were reportedly processed by Chadian intelligence agents and escorted into the city (X.com/TchadOne, April 28). The troops themselves were Hungarian, however, part of a mission approved on November 7, 2023.

The Hungarian mission has three stated aims: deterring illegal migration to Europe, aiding counter-terrorism efforts, and providing a secure base for economic and humanitarian assistance (Defence.hu, October 30, 2023). While the Hungarian government under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has adopted a stance sympathetic to Moscow, there has been no indication that the Hungarian deployment has any connection to Russian activities in Chad. Budapest’s objectives in Chad may actually clash with those of the Kremlin, which is believed to be intent on increasing the flow of migrants to Europe through Libya (Libya Observer, March 7).

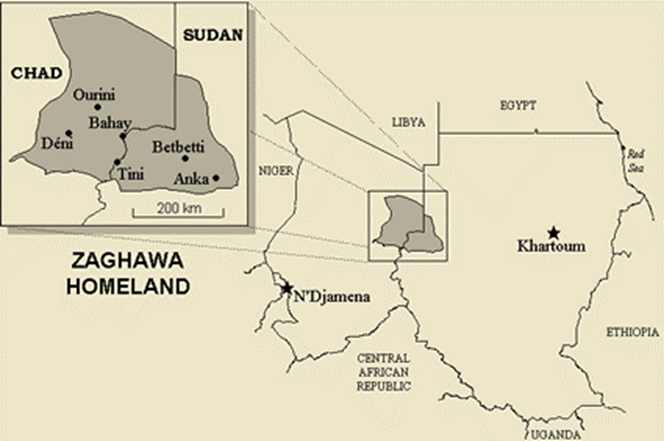

Chad is unlikely to make a sudden leap into the Russian camp. The late Idriss Déby Itno routinely played off one potential partner after another, always returning to the French after they had been reminded Chad’s allegiance was neither automatic nor unconditional. Moreover, Chad has not undergone a drastic change of regime seen in other Sahel states. It remains in the hands of the late president’s son and a cabal of Zaghawa relatives that occupy senior posts in the army and the administration. The Zaghawa ethnic group represents less than 3 percent of the population (Al Jazeera, December 26, 2023, February 29). Asked whether he intended to switch Chad’s military alliance from France to Russia, Mahamat replied, “Chad is an independent, free, and sovereign country. We are not like a slave who wants to change masters” (RFI, April 15). He added that economic cooperation was more important to the country than defense cooperation. France is a major trade partner for Chad, while trade with Russia is nearly nonexistent (Russia Today, January 28).

Chad remains desperately poor, other than the oil revenues that never seem to trickle down to the masses. The country needs the trade that France offers but Russia cannot. The regime, composed of a tiny ethnic minority, needs little instruction on Russian techniques of political repression. The sudden dalliance with Moscow, so closely aligned with an election intended to restore permanent Déby clan rule, was a reminder to the West that calls for democracy are not the key to a military alliance. As proof of this approach’s effectiveness, on March 7, the French president’s personal envoy to Africa stated that the French army would remain in Chad to support its “independence,” apparently without preconditions (AFP, March 15).

Mahamat himself has created divisions within the ruling Zaghawa elite by retiring many Zaghawa generals close to his father while promoting members of the Arab and Gura’an (Tubu) minorities (Mahamat’s mother is from the Gura’an) (Al-Masry al-Youm, May 18). The Zaghawa of Chad have close ties to the Zaghawa of Darfur in Sudan who have suffered from the rampages of the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Mahamat’s decision to allow the United Arab Emirates to supply the RSF with arms and other supplies through Chadian territory has created further rifts within the country’s Zaghawa community.

Mahamat himself has created divisions within the ruling Zaghawa elite by retiring many Zaghawa generals close to his father while promoting members of the Arab and Gura’an (Tubu) minorities (Mahamat’s mother is from the Gura’an) (Al-Masry al-Youm, May 18). The Zaghawa of Chad have close ties to the Zaghawa of Darfur in Sudan who have suffered from the rampages of the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Mahamat’s decision to allow the United Arab Emirates to supply the RSF with arms and other supplies through Chadian territory has created further rifts within the country’s Zaghawa community.

Any move by Chad’s young president toward replacing the steady French partnership with an unpredictable Russian presence would likely be met with strong resistance from the armed forces. Unlike their counterparts in other countries of the Sahel, Chadian military leaders have not shown a public preference for Russia.