Andrew McGregor

March 21, 2013

Though it lacks the compelling and convenient images produced in Cairo’s Tahrir Square during Egypt’s dramatic January, 2011 revolution, Egypt has been plunged into what has been variously described as a counter-revolution, a continuation of the 2011 revolution or an attempt by Islamist forces to consolidate power by taking advantage of Egypt’s internal security crisis. With police walking away from their duties across the country, Egyptians are seeking solutions to a security collapse that has given free rein to criminals, vandals and political extremists. Solutions such as massive reforms in the Interior Ministry or even privatization of the police have been floated, but Egypt’s Islamist movements have come up with their own solution – the creation and deployment of Islamist militias known as “popular committees.” The inability of the government to deal with the ongoing security crisis and the growing divide between Egypt’s religious and secular communities has many Egyptian politicians and commentators raising the possibility of a civil war.

Public protests have been fueled by economic turmoil, fuel shortages and controversial court decisions such as the acquittal of seven police officers tried for their role in the soccer-related violence that claimed 74 lives in Port Said in February, 2012 (21 civilians have been sentenced to death for their involvement in the violence) (al-Arabiya, March 11). Ongoing strikes in the industrial sector have paralyzed economic development.

Public protests have been fueled by economic turmoil, fuel shortages and controversial court decisions such as the acquittal of seven police officers tried for their role in the soccer-related violence that claimed 74 lives in Port Said in February, 2012 (21 civilians have been sentenced to death for their involvement in the violence) (al-Arabiya, March 11). Ongoing strikes in the industrial sector have paralyzed economic development.

Some demonstrations have involved shutting down public transportation and assaulting railway passengers, behavior that was unthinkable in pre-revolution Egypt (Ahram Online, February 11). Even the Mugamma building, Egypt’s monument to labyrinthine bureaucracy in Tahrir Square, has been subject to assault by demonstrators as security forces stood by (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], February 24). Cairo’s “Ultra” soccer hooligans have also engaged in vandalism and public violence in their deadly feud with Egypt’s security forces. A Muslim Brotherhood website has claimed that former leading officials of the now dissolved National Democratic Party (NDP – the ruling party of the former regime) are instigating the Ultras to attack the Muslim Brothers (Egyptwindow.net, March 15). Several days later, the same website claimed that former NDP members were alternately bribing citizens to go on strike or forcing them to strike at gunpoint (Egyptwindow.net, March 18).

In a troubling development, weapons appear to be pouring into the traditionally unarmed civilian population of Egypt since the revolution and the collapse of the Qaddafi regime in neighboring Libya. A recent sweep by Egyptian police seized 423 weapons, including machine guns and rifles (Middle Eastern News Agency [MENA – Cairo], March 17).

In what could be an embarrassing challenge to Egypt’s pretensions of leading the Arab world, reports have emerged that the Arab League is considering moving its headquarters out of Cairo due to continued violence that has forced the group to relocate many of its meetings (Ma’an News Agency [Bethlehem], March 18). Foreign investment is in steep decline and Egypt’s tourist industry, a vital source of hard currency, is floundering as Western tourists look for more secure places to vacation. For Egypt’s Islamists, however, this is not necessarily a bad thing, as they seek to replace Western tourists with Muslim tourists from the Gulf States, though the latter seem to be avoiding Egypt as well.

Citizen’s Arrests or Privatization?

Egypt’s prosecutor-general Talat Abdullah (an appointee of Egyptian president Muhammad Mursi) created a storm of controversy by urging “all citizens” to combat the destruction of private and public property and the creation of roadblocks by exercising “the right afforded to them by Article 37 of Egypt’s criminal procedure law to arrest anyone found committing a crime and refer them to official personnel” (Ahram Online [Cairo], March 10; al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 12). A later statement from Abdullah’s office tried to back away from advocating citizen arrests, but had little impact.

Article 37 is an existing but little-used piece of legislation that allows citizens to arrest defendants for offenses that can be punished by no less than one year in prison – making an arrest on lesser offences could result in a charge of illegal arrest. These provisions are clearly designed to limit the use of Article 37, but these details are likely to be overlooked in the current heated environment. According to a military source cited by a major Cairo daily, “The statements of the prosecutor-general regarding granting citizens arrest powers are a clear attempt to legalize the militias of the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists on the streets and to give them the right to arrest citizens, which puts Egypt on the verge of a civil war and ends the state of law” (Ahram Online, March 11).

While secular opposition parties denounced the prosecutor-general’s statement as an attempt to legitimize Islamist militias and a violation of the constitution, the secretary general of the Islamist Hizb al-Bena’a wa’l-Tanmia (Building and Development Party) Ala’a Abu al-Nasr, hailed the announcement, saying “The decision of the prosecutor-general to grant citizens the right to arrest vandals is a correct decision based on the law… The decision comes as a first step to confront systematic violence in Egypt” (Ahram Online, March 11).

The dismissal of prosecutor-general Abdullah and the resignation of the government of Prime Minister Hisham Qandil are among the demands an opposition coalition, the National Salvation Front, has said must be met before they will participate in forthcoming parliamentary elections (Ahram Online, March 14). Talat Abdullah has submitted his resignation once already since his November 2012 appointment after hundreds of public prosecutors staged a sit-in outside his office (al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 12). The largest of Egypt’s Salafist parties, the Nur Party, is also backing calls for the replacement of the Qandil government.

On March 9, Sabir Abu al-Futuh, a senior member of the Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing, Ḥizb al-Ḥurriya wa’l-Adala (FJP – Freedom and Justice Party), announced that the party was considering legislation that would give private security firms the right to bear arms, make arrests and be engaged by the state to provide domestic policing functions. Abu al-Futuh also recommended the establishment of armed “popular committees “in the event that police continue their strike action.” Ahmad Fawzi of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party called Abu al-Futuh’s proposal “a continuation of the Islamist group’s ongoing endeavors to monopolize power in all of its forms, whether it be police, army or judiciary” (Ahram Online, March 10). Some Egyptians warn that privatization of the domestic security services would open the way for U.S. security firms to set up shop in Egypt with the approval of their “friends” in the Muslim Brotherhood (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], March 16).

The Interior Ministry

Striking police oppose what they describe as the “Brotherhoodization” of the Interior Ministry and call for the dismissal of another Mursi appointee, Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim (Ahram Online, March 15). Scores of police stations and Central Security Force (CSF) camps across Egypt (including those in the main cities of Cairo and Alexandria) have joined the strike that began March 7 when security forces in the Suez town of Ismailiya refused to deploy to Port Said, where several police officers have been killed in ongoing unrest. Egypt’s security services are still reeling from the public contempt that followed their brutal response to the anti-Mubarak revolution and fear that association with the ruling party will only further alienate the security forces from the public. According to one striking policeman, “We don’t want to be hated and feared by the people; we don’t want to be treated as the enemies of the people and the servants of the regime” (Daily News Egypt, March 9). The striking policemen are also calling for better arms to tackle the wave of lawlessness sweeping Egypt.

Many policemen have been suspended after growing beards to express their affiliation with Islamist movements. Though an Administrative Court ruled in favor of the “bearded policemen” on the grounds of religious freedom, the Interior Ministry has refused to follow the court’s ruling, leading to further demonstrations and the creation of an official Facebook page: “I am a bearded policeman” (Ahram Online [Cairo], March 14). There are now also demands from some members of the army that they be allowed to grow beards, demands that have been interpreted in some quarters as an attempt to turn the army into an armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood (al-Watan [Cairo], March 17).

Many policemen have been suspended after growing beards to express their affiliation with Islamist movements. Though an Administrative Court ruled in favor of the “bearded policemen” on the grounds of religious freedom, the Interior Ministry has refused to follow the court’s ruling, leading to further demonstrations and the creation of an official Facebook page: “I am a bearded policeman” (Ahram Online [Cairo], March 14). There are now also demands from some members of the army that they be allowed to grow beards, demands that have been interpreted in some quarters as an attempt to turn the army into an armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood (al-Watan [Cairo], March 17).

One of the early victims of the police strikes was the CSF commander, Magid Nouh, who was replaced on March 8 by CSF veteran Ashraf Abdullah after he failed to persuade the security services to allow him to return to work (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], March 8; al-Jazeera, March 8). The Egyptian president followed this move by making a personal visit to the Cairo headquarters of the CSF where he returned to the familiar language of “external threats” by warning the officers: “Beware, our outside enemy is seeking to create division among us, and we must not allow it” (Ahram Online [Cairo], March 15).

Al-Gama’a al-Islamiya

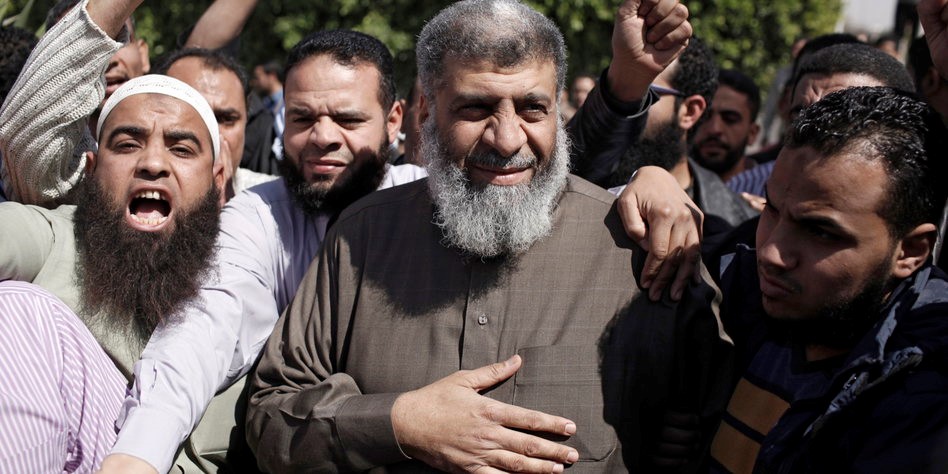

Leading the effort to form “popular committees” is al-Gama’a al-Islamiya (GI), a Salafist group that turned to non-violence after a long record of terrorist attacks through the 1980s and 1990s. Many leading members of the GI and BDP are former militants released from prison during the 2011 revolution.

According to a spokesman for the BDP, the GI’s political wing, “community police groups would step in under the supervision of the Interior Ministry,” while claiming that “this system is applied in other countries” (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], March 12). Another BDP spokesman has complained the police are forcing the people to choose between torture or a lack of security: “We call on the police to meet their duty in protecting state institutions and not to give up the country’s security and stability in such critical times” (Ahram Online, March 9).

Asim Abd al-Magid, a senior GI member, has been given the job of organizing the GI’s “popular committees.” Besides calling on Egyptians to gather at mosques to form militias, Abd al-Magid has shown only slight respect for the security services: “Any policeman who wants to leave his position can do so, but he will not be allowed to come back… We want to purge the ministry of such elements anyway” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 12).

Satellite television has carried footage of the “Gama’a al-Islamiya police” parading in the streets of Asyut in cars and motorcycles despite warnings from the police that their activities are illegal (al-Hayat TV, March 12). In the city of Minya, the BDP has joined with the Salafist Nur Party to form “popular committees” to restore order in the streets (Ahram Online, March 9).

The Muslim Brotherhood

The vice-president of the FJP (the Brothers’ political wing), Dr. Rafiq Habib (a Coptic Christian), believes that the chaos in Egypt’s streets is the work of secular forces and representatives of the old regime who see the violence as a means of preventing the Islamists from governing the country effectively, thus opening an opportunity for the restoration of the old regime (sans Mubarak) (Egyptwindow.net, March 15).

The Brotherhood has been unnerved by a series of arson attacks on its offices throughout Egypt that began last December. At times, these attacks have resulted in pitched street battles between anti-Brotherhood protestors and Brotherhood self-defense groups (Amal al-Ummah [Alexandria], March 19). In an effort to come to grips with the spiraling violence, the leader of the Muslim Brothers, Dr. Muhammad Badi, launched an initiative on March 16 that calls for all the various political factions to remove their supporters from the streets for a specific period of time so that maximum efforts can be made to re-build the country (Egyptwindow.net, March 17).

The possibility of Islamist militias taking to the streets reminded many Egyptians of the shocking photos published in 2006 that showed a military display at Cairo’s Islamic al-Azhar University put on by a Muslim Brotherhood student group known as “the Hawks,” though the event was later dismissed by the Brotherhood as nothing more than “a theatrical display” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, December 13, 2006). More recently, Cairo’s al-Dustur daily reported on March 20 that Muslim Brotherhood members had received military training at CSF camps in preparation for fielding militias, though the Interior Ministry has denied these claims.

The Army

Demonstrations in Alexandria have called for the resignation of President Mursi, the trial of Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim on charges of killing demonstrators in the Suez region and the return of the army to run the country until new elections can be held (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], March 8). A recent poll by Cairo’s Ibn Khaldun Center for Development Studies showed a surprising 82 percent of Egyptians want the army to take control of the country on a temporary basis (al-Masri al-Youm [Cairo], March 18). The poll results were released days after residents of al-Nasr City took to the streets on March 15 to demand a return to military rule (MENA, March 15). Calls for the return of the army are also beginning to appear with frequency in the non-Islamist Egyptian press.

Defense Minister General Abd al-Fatah al-Sisi maintains that the “Brotherhoodization” of the military is a near impossibility, but has warned recruits to abandon sectarian or political allegiances when they enter the military (al-Ahram [Cairo], March 15). Whether they form the government or not, the Muslim Brotherhood cannot easily transform the leadership of an institution that has spent decades purging all officers suspected of being sympathetic to the Brothers. While the situation could be changed very gradually through loosening restrictions on officer-candidates, command of the military cannot be simply handed over to a group of inexperienced Islamist subalterns. The Islamization of the military could more realistically take one or two decades – any sudden attempt to transform the military would inevitably result in yet another coup d’état and a return to military rule. The military’s surprising cooperation with the Brotherhood so far has raised the possibility that the command has simply given the Islamists enough rope to hang themselves in trying to transform a deeply entrenched social and political system. When popular opinion cries out for a return to the stability of military rule and foreign governments begin to give indications they are ready to look the other way, the military will be in a prime position to return to government or install a more pliant regime. The Army still controls a large but undefined section of the national economy, making it a necessary partner in any shift in political direction.

Conclusion

Before his death last year, former Egyptian intelligence chief General Omar Sulayman warned of the creation of Islamist militias in Egypt and the consequent threat of a civil war: “The Muslim Brotherhood group is not foolish, and hence it is preparing itself militarily, and within two to three years it will have a revolutionary guard to fight the army, and Egypt will face a civil war, like Iraq (al-Hayat, May 22, 2012; see also Terrorism Monitor Brief, June 1, 2012).

The Egyptian Army has indicated that the creation of private militias is a “red-line” for the military that could bring on military intervention to restore state control (Ahram Online, March 11). Interior Minister Ibrahim has insisted there is no role for vigilantes or militias in Egypt: “From the minister to the youngest recruit in the force, we will not accept having militias in Egypt. That will be only when we are totally dead, finished” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, March 12). For Egypt, however, the greatest challenges to internal security may be yet to come, as Egyptian jihadists return from the battlefields of Syria and exiled Egyptian members of core al-Qaeda take advantage of the security collapse to re-infiltrate the country and resume the type of bloody operations that marked the struggle between Islamist terrorists and security forces in the 1990s.

This article first appeared in the March 21, 2013 issue of the Terrorism Monitor’s Terrorism Monitor