Andrew McGregor

May 15, 2008

Last weekend’s daring raid on greater Khartoum by Darfur’s rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) has shaken the regime and effectively disrupted the already morbid peace process in West Sudan. Though often referred to as a Darfur rebel group, JEM in fact has a national agenda, much like John Garang’s Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Army (SPLA), which always maintained it was a movement of national liberation rather than a southern separatist group. Until 2006, JEM was also involved militarily in the revolt of the Beja and Rashaida Arabs of Eastern Sudan against Khartoum.

(The Economist)

The Zaghawa tribe that straddles Darfur and Chad dominates the JEM leadership, marking a major challenge to traditional Arab superiority in Sudan. While some of the leaders of Darfur’s badly-divided rebel groups have fought the rebellion from the cafés of Paris, JEM leader Khalil Ibrahim has remained at the front, forging a disparate group of refugees, farmers and ex-military men into the strongest military force in Darfur and the greatest threat to the Sudanese regime.

Greater Khartoum consists of the capital, Khartoum, the city of Omdurman on the western side of the White Nile, and the industrial suburb of Khartoum North on the north side of the Blue Nile. Khartoum itself is protected by broad rivers to the west and north, making assaults from these directions extremely difficult. Despite decades of warfare in Sudan’s provinces, Khartoum has not experienced any fighting in its streets since 1976, when Libyan-trained Umma Party rebels—also from West Sudan—fought running gun-battles in a failed attempt to overthrow the military government.

The once dusty and decaying Sudanese capital has undergone an astonishing transformation in recent years due to growing oil revenues and massive investment from the Gulf, Malaysia and China. Khartoum has increasingly become an island of prosperity surrounded by a vast and impoverished hinterland that now calls for an equitable distribution of the national wealth.

Across the Desert to Khartoum

On May 8, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) reported they had learned of “preparations made by rebel Khalil Ibrahim to conduct a sabotage attempt and a publicity stunt through infiltrating the capital and other towns” as well as noting that “groups riding vehicles” were headed east from the Chadian border (Sudan Tribune, May 8). A JEM commander reported that the column consisted of 400 vehicles and took three days to reach Khartoum (AFP, May 11). Notably absent from the attack were forces from the Sudan Liberation Army – Unity (SLA-Unity), another Darfur rebel group that has operated in a military alliance with JEM for the past two years.

A government spokesman claimed that the armed forces met the rebel column in Kordofan, at a point 75 mi west of the capital, where a portion of the rebel force made a run for Omdurman after most of the column had been stopped by a government attack.

JEM claims to have hit the Nile north of Omdurman, seizing and looting the Wadi Saidna Air Force base, 10 miles north of Khartoum. This claim has not been verified, but eyewitnesses reported seeing an attack on the base (Sudan Tribune, May 11).

On Friday night, May 9, Khartoum’s embassies received calls from the government warning them of a possible rebel attack on Khartoum (AFP, May 10). Despite the incoming reports of a JEM column heading east across the desert, Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir continued performing the umrah (the minor pilgrimage) in the holy cities of Saudi Arabia. With Bashir in Saudi Arabia, the acting president was First Vice President Salva Kiir Mayadrit of the SPLA, who maintains he was in constant contact with al-Bashir until his return late on May 10.

Assault on the Suburbs

On May 10, some 150 armored pick-up trucks reached the outskirts of Omdurman. With helicopters in the air, security personnel poured into the streets, setting up checkpoints and securing potential targets. The bridges linking Omdurman to Khartoum across the White Nile were blocked.

Despite bold claims from JEM spokesmen that their forces were “everywhere in the capital,” it appears that few, if any, of the rebels managed to penetrate much farther than the suburbs of northern Omdurman, where their burning pick-up trucks could be seen after the battle. Claims by rebel commanders that their troops had seized the bridges and entered Khartoum appear to have been wishful thinking or an attempt to unnerve the regime.

Throughout the attack, media-savvy JEM field commanders were on the phone to major international media sources, giving progress reports with the sound of gunfire and explosions in the background. A commander called Abu Zumam claimed his forces had entered Omdurman and were preparing to seize the National State Radio building (Radio Omdurman). Another JEM commander named Sulayman Sandal was also in constant contact with media. As the government counter-attacks began to drive JEM fighters from the city, Commander Sulayman insisted: “This was just practice. We promise to hit Khartoum one more time unless the [Darfur] issue is resolved” (AP, May 11). The commander claimed JEM forces had initially seized all of Omdurman, but were beaten off due to the inexperience of JEM troops in urban warfare (AFP, May 11).

Sudan’s official news agency SUNA claimed that JEM’s “military commander” Jamal Hassan Jelaladdin was killed on the outskirts of Khartoum in the morning of May 11. SUNA also reported the deaths of Muhammad Saleh Garbo and Muhammad Nur al-Din, described as the leader of the attack and the JEM intelligence chief, respectively (SUNA, May 11). JEM reported that no one by these names were in the rebel ranks, but claimed Jamal Hassan had been captured and summarily executed after his vehicle broke down (Sudan Tribune, May 12).

What Were the Targets?

JEM spokesman Ahmad Hussein Adam declared that Wadi Saidna air force base was targeted because it was “the base from where all Sudanese military planes go to Darfur” (AFP, May 10). Heavy civilian losses were reported in Northern Darfur in the weeks preceding the raid on the capital. JEM recently accused Khartoum of recruiting 250 Iraqi pilots to carry out bombing missions in Darfur following combat losses and a reluctance by Sudanese pilots to continue bombing civilian targets (Sudanjem.com, May 4).

State radio facilities head the list of desirable targets on any coup-leader’s target list—in this case Radio Omdurman was no exception. JEM may have anticipated that the residents of Khartoum were only awaiting a sign to rise up against the government, but there appeared to be no verifiable instances of tri-city residents offering material support to the rebels. With residents confined indoors by a curfew, parts of the city were remarkably quiet.

When the bridges across the Nile were secured by Sudanese security forces it became impossible to complete JEM’s objectives. There does not appear to have been any backup plan for this fairly predictable circumstance. When asked by the BBC how he plans to deal with this problem in his promised return to the capital, Khalil Ibrahim responded; “I am not empty handed. I took a lot of things from Khartoum—a lot of vehicles, ammunition and money” (BBC, May 12). There are reports that a large quantity of weapons and ammunition were seized at the Wadi Saidna air base.

According to VP Salva Kiir, the rebel targets in the capital included Radio Omdurman, the military headquarters and the presidential palace beside the Blue Nile (Sudan Tribune, May 13).

Mopping Up

When the JEM attack crested in the suburbs of Omdurman many fighters found themselves without any means of escaping the city. Some surrendered while others were reported to have doffed their camouflage gear in favor of civilian clothing. Gunfire continued throughout the weekend as security forces tried to flush out hidden JEM fighters. Reports of gunfire in the center of Khartoum were apparently the result of edgy security men firing on a group of civilians hiding in a building (BBC, May 12). When the fighting had stopped, government forces stated 400 rebels and 100 security men had been killed.

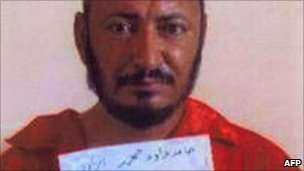

Security forces reported seizing 50 rebel pick-up trucks while battered prisoners were repeatedly displayed on state television. With continuing reports that Khalil Ibrahim had gone into hiding in Omdurman after being injured when his truck was hit by gunfire, Sudanese state television broadcast his photo for the first time, encouraging viewers to report any sightings. A reward of $125,000 for information leading to the JEM leader’s capture was later doubled to $250,000.

Despite the lack of any public support in Khartoum for the rebels, security forces quickly decided that the attack must have relied on a fifth column within the city. This prompted mass arrests of Darfuris in the capital, especially those of the Zaghawa tribe (Sudan Human Rights Organization statement, Cairo, May 13). Some Darfur groups reported the arrest and beatings of thousands of Darfuri laborers working in the capital (al-Jazeera, May 13). Other reports claim dozens of Zaghawa in the city have been executed (Sudan Tribune, May 13). A JEM spokesman described the arrests as “ethnic cleansing” (Sudan Tribune, May 10).

Sudan’s leading Islamist, Hassan al-Turabi, was detained for questioning by security forces due to his former association with JEM. Khalil Ibrahim was once described as a follower of the controversial al-Turabi, but there appear to be few, if any, ties remaining between the two. Turabi and several other members of his Popular Congress Party were quickly released after questioning.

The Role of the Army and Security Forces

The majority of the rank-and-file in Sudan’s army comes from the African tribes of Darfur and Kordofan. They are typically led by Arab officers from the Northern Province of Sudan. Most of the fighting in the capital appears to have been done by government security services and police rather than the military. VP Salva Kiir notes that the army did not intervene until it became clear the rebels had been repulsed (Sudan Tribune, May 13). Some mid-level army commanders are reported to have been arrested after the attack.

Reacting to public criticism of the military’s failure to stop the assault long before it reached Khartoum, a presidential adviser claimed that the military had intentionally drawn the rebels “into a trap” (Sudan Tribune, May 13). Sudanese Defense Minister Abdel-Rahim Muhammad Hussein was roundly condemned by members of parliament who called for an inquiry as to how JEM forces could reach the capital (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, May 14; Sudan Tribune, May 14). While some MPs called for his resignation, the Defense Minister blamed the U.S. embargo for the lack of surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft.

Destroyed JEM Vehicle in the Streets of Omdurman

Destroyed JEM Vehicle in the Streets of Omdurman

After returning to Darfur, Khalil Ibrahim thanked the neutrality of the Sudanese army, which “welcomed him” (Sudan Tribune, May 13). This statement alone will create chaos in the security structure as the government seeks out real, potential and imagined collaborators.

Reaction of the SPLA

JEM frequently states its commitment to the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed by the southern Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Army (SPLA) and the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). At the same time, it is vehemently opposed to the idea of southern separation—the CPA calls for a referendum on southern separation in 2011, a position that has interfered with JEM efforts to forge stronger ties with the SPLA. Regarding any attempt to overthrow the government as interference in implementing the CPA, the SPLA’s military commanders offered Khartoum the use of SPLA troops still under Salva Kiir’s command.

Proxy War with Chad?

Last March, N’Djamena and Khartoum signed yet another in a series of worthless peace agreements after an attack by Sudanese-supported rebels nearly deposed the Zaghawa-based government of President Idriss Déby. Khartoum has accused Chadian forces of mounting a diversionary attack on the SAF garrison at Kashkash along the Chad/Sudan border “meant to support the attempt of sabotage of the rebel Khalil Ibrahim” (Sudan Tribune, May 10). The SAF claimed to have successfully repulsed the Chadian troops, forcing them to pull back across the border.

On his return from pilgrimage, Bashir severed relations with Chad and laid the blame for the raid on the “outlaw regime” in N’Djamena: “These forces come from Chad who trained them … we hold the Chadian regime fully responsible for what happened.” Perhaps unwilling to admit the military potential of the Darfur rebels, Bashir claimed: “These forces are Chadian forces originally, they moved from there led by Khalil Ibrahim who is an agent of the Chadian regime. It is a Chadian attack” (AP, May 11). The SAF claimed that most of the prisoners were Chadian nationals. A Chadian government spokesman quickly denied any official involvement in the attack (AFP, May 10).

Chadian officials reported that uniformed Sudanese security forces broke into all the offices of the Chadian embassy in Khartoum, seizing documents and computers (Sudan Tribune, May 11). The Sudanese Foreign Ministry claimed: “We have evidence there was communication between [the rebels and] the government of Chad and the embassy of Chad in Khartoum” (AFP, May 11).

China Stays Aloof

Though China has natural concerns over the effect of a regime change in a country that is now one of its largest foreign oil suppliers, the reaction from Beijing was supportive but muted. JEM has made clear its opposition to China’s oil operations in Sudan, attacking Chinese oil facilities in Kordofan (see Terrorism Focus, September 11, 2007). JEM is also angered by the Chinese supply of arms and warplanes to the Khartoum regime. China was one of the few non-African countries approved by Khartoum for participation in UNAMID, contributing a group of military engineers to the Darfur peacekeeping efforts. In a Foreign Ministry statement, China condemned the attacks but hoped “the Darfur armed rebel group could join in the political process as soon as possible and resume negotiation with the Sudanese government, for the early signing of a comprehensive peace agreement, to realize peace, stability and development in Darfur” (Xinhua, May 11).

What Next for the Regime? For JEM?

Khartoum declared negotiations with JEM to be at an end on May 14, but this will make little difference since JEM was already not part of the ongoing negotiations with other Darfur rebel groups. Presidential adviser Mustafa Osman Ismail promised government retaliation instead: “From this day we will never deal with this movement again other than in the way they have just dealt with us” (Xinhua, May 11). President Bashir has also claimed that Israel funded the assault, calling Khalil Ibrahim “an agent… who sold himself to the devil and to Zionism” (AP, May 14). The government is demanding that JEM be declared an international terrorist organization by the United States and the UN (Radio Omdurman, May 13).

The raid on Khartoum was a reminder to the Northern Arab regime that it might all come crashing down one day and that their continued wealth and power is by no means guaranteed. After the raid, Khalil Ibrahim provided this justification for the attack: “The Sudanese government killed 600,000 people in Darfur and they are living at peace in Khartoum” (al-Jazeera, May 13). Whether the raid results in greater conciliation efforts and distribution of wealth to the provinces is yet to be seen. Past experience suggests that the government’s response will be increased violence and repression. Large-scale retaliation against Chad is virtually inevitable. In the meantime Khartoum may have to deal with a sudden reluctance on the part of international investors to put their money into an uncertain situation.

Khartoum will undoubtedly implement measures to prevent a repeat of the attack, but JEM has also learned several important lessons in this operation. It is difficult to believe that JEM intended to hold and seize the city at this time, but the operation may lay the groundwork for a larger effort in the future. More plausible is Khalil Ibrahim’s claim that he intends to exhaust and divide the Sudanese military by spreading the war far beyond Darfur (AP, May 13). According to the JEM leader, “This is just the start of a process and the end is the termination of this regime” (BBC, May 12).

This article first appeared in the May 15, 2008 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

Local Security: The Bajaur Scouts

Local Security: The Bajaur Scouts