Dr. Andrew McGregor

Research Note, Royal Canadian Military Institute, January 2026.

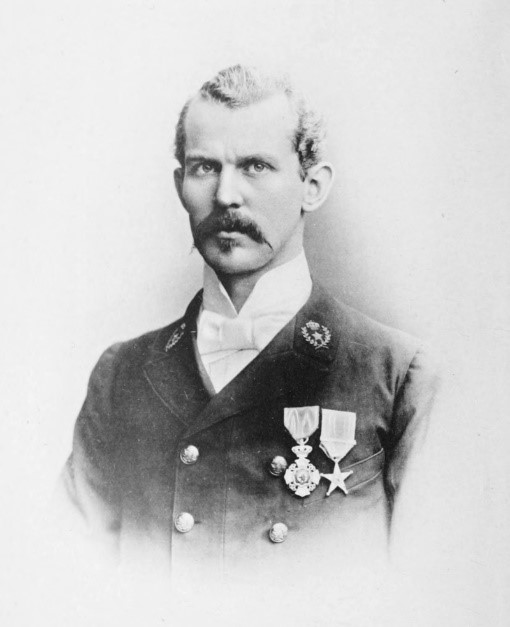

Dr. Sidney Langford Hinde wearing his Congo decorations.

Dr. Sidney Langford Hinde wearing his Congo decorations.

In the histories of the great 19th century “Scramble for Africa,” Canada is rarely, if ever, mentioned. The young nation had no colonial designs on Africa, but was still part of the British Empire, which was battling its European neighbours and African resistance movements for control of vast regions of the continent. It was inevitable, then, that some Canadians would become involved in this struggle, though not all worked in British interests.

Among those Canadians who distinguished themselves in British service in Africa were Toronto’s Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Charles Denison, who commanded the Canadian voyageurs on the Nile in 1884-1885; Montreal’s Lieutenant Raymond de Montmorency, who earned a VC at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898 before his death at the Battle of Stormberg in South Africa two years later; and RMC graduate Sir Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, of Montreal, who built a military railway across the Sudanese desert that permitted the movement of the Egyptian and British armies south to Omdurman to defeat the Mahdist forces of Khalifa ‘Abd Allahi in 1898.

Others, however, found themselves part of the international group of mercenary officers serving King Leopold II of Belgium in the king’s private African possession, the Congo Free State (1885-1908). The task of these officers, mostly Belgian, was to expand and consolidate King Leopold’s massive estate, often at the expense of British competitors. The best known of the Canadians in Leopold’s employ was Halifax’s William Grant Stairs, an RMC graduate who traveled 5000 miles across Africa in Henry Morton Stanley’s Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1887-1889). He then led his own expedition to mineral-rich Katanga (1891-1892), seizing this region for the Congo Free State by killing King Msiri, the local potentate.

A lesser known but important Canadian-born contributor to the establishment of the Congo Free State was Dr. Sidney Langford Hinde. Hinde was born somewhere in the Niagara region on July 23, 1863, the son of Irish surgeon Major-General George L. Hinde. Educated in France and Germany, Hinde followed his father’s medical career, working in London hospitals before taking service with Leopold’s Congo Free State in 1892. Fluent in French, Hinde was recommended by Irish physician and British Army officer Thomas Heazle Parke, doctor on Henry Morton Stanley’s Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1887-1889).

When Hinde joined the Free State military, Arab-led Mahdists controlled the Sudan and were pressing south into the Congo region, while Omani-origin Arabs had turned Zanzibar into a base for expansion into east and central Africa. A Spectator article of 1897 portrayed a struggle between Whites and Arabs for Africa: “The White has been fighting the Arab at Dongola, on the Congo, on the Lakes, on the East Coast, and even at Zanzibar itself.”

Britain’s Royal Navy had been active in trying to suppress the shipment of slaves from the African coast to the Middle East since 1822, with varying levels of success. Arab clove plantations in Zanzibar relied on the labor of thousands of Black slaves. In 1873 the British forced Zanzibar’s Omani rulers to abandon the slave trade, though it continued on the mainland.

The most powerful of the slavers in eastern Africa was the Arab/Swahili Tippu Tip (Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab al-Murjabi), who at one point maintained personal ownership of 10,000 slaves on his Zanzibar plantations. In the mid-1880s, Tippu Tip claimed the eastern Congo for himself and the Sultan of Zanzibar. It was Tippu’s son Sefu bin Hamad who led the Arab slavers at the time of Hinde’s service in the Congo during the Congo-Arab War (1892-1894). Sefu’s partner was Rumaliza (Muhammad bin Khalfan bin Khamis al-Barwani), a powerful Omani/Swahili trader in slaves and ivory. He was famous for inventing depraved tortures, too gruesome to be discussed here.

The conflict was touched off by a dispute between Belgians and Arabs over ivory, not slaves, but for political purposes it was quickly recast in Europe as a Christian anti-slavery crusade, though Free State columns usually included large numbers of slaves belonging to the African troops in the Force Publique (the Free State army). Force Publique regulars were mostly Zanzibaris and Hausas recruited in West Africa, and were accompanied on campaign by thousands of local “auxiliaries,” largely cannibals of fluid loyalty. Discipline was maintained through regular flogging.

Steady fighting through 1893 drove the Arabs east, resulting in the death of Sefu in October 1893. Rumaliza met defeat in the war’s final battle in January 1894, when a Belgian shell blew up his ammunition dump and set fire to his fort at Bena Kalunga. Rumaliza’s men were slaughtered as they tried to escape while 2,000 others were taken prisoner. The war shattered the power of the Arabs in eastern and central Africa, damaged the Arab trade in slaves and diverted the Congo’s trade from east African ports down the Congo River to Atlantic coast ports. Under heavy international pressure as news of the cruel nature of his rule in the Congo began to emerge, Leopold II transferred control of his personal estate in Africa to the Belgian government in 1908. Leopold never visited the land he had ruled for 23 years.

Hinde recounted his adventures in the Congo in The Fall of the Congo Arabs (London, 1897), translated into French the same year as La Chute de la domination des arabes du Congo (Brussels, 1897). Acting not only as a doctor, Hinde was personally involved in the vicious fighting that characterized the campaign. It should be noted that Hinde’s Congo service was nearly always in the field and there does not appear to be any evidence of his implication in the crimes for which the Free State became famous, only for his unwitting enablement of them.

Transferring to the British Foreign Office in 1895, Hinde became a provincial commissioner in the British East Africa Protectorate. While resident in Kenya, Hinde produced a second book, Last of the Masai (London, 1901), co-written by his wife, naturalist Hildegarde Beatrice Hinde. He died in Wales in 1930, age 67.

Hinde’s Grave in Pembrokeshire, Wales.

Hinde’s Grave in Pembrokeshire, Wales.

This note has its origins in the author’s search for confirmation that Hinde was indeed born in Canada, as many websites claim while failing to provide appropriate documentation. An 1891 census of England, however, records London resident Sidney Langford Hinde having been born in Canada, which would seem to confirm his Canadian origin through information he himself provided. Hinde’s Niagara origin is confirmed in the Biographie Coloniale Belge (Institut Royale Coloniale de Belge, T. 1, 1948 col. 509-513).

That Hinde and his Free State comrades have been consigned to historical obscurity is unsurprising. Their defeat of the Arab slavers might have been hailed as a triumph of Western civilization had Leopold and his henchmen not instituted their own savage form of forced labor and its trail of murder, torture and mutilation to meet the demands of the late 19th century rubber boom. The methods of the Free State mercenaries and foremen came to resemble those of the Arab slavers they had run out of the Congo.

1921 Brussels Monument to the Belgian Pioneers in the Congo. The references to “Arab” slavers have been chiseled out in recent times.(Sam Donvil)

1921 Brussels Monument to the Belgian Pioneers in the Congo. The references to “Arab” slavers have been chiseled out in recent times.(Sam Donvil)

Eventually, the role of Hinde and others came to be regarded as part of a shameful episode in European colonization, while well-funded campaigns by the Arab League have helped rehabilitate the image of the Arab slavers, portraying them as explorers and traders bringing Islam to the African interior. The appalling first-hand accounts of large-scale cannibalism by native fighters of both sides as described in detail by Hinde and others have also helped relegate memory of the Congo-Arab War to one of the darkest, least-examined corners of the “Scramble for Africa.”

Note: The careers of Canadian soldiers who served in British forces in 19th century West Africa are described in: Andrew B Godefroy, “Canadian Soldiers in West African Conflicts, 1885-1905,” Canadian Military History 17(1), 2008, pp. 21-36.

This Research Note appeared in the January 2026 issue of the Royal Canadian Military Institute’s Members’ News – https://files.constantcontact.com/e154b138001/cd18bb33-88e1-44c7-a729-d471cbfaa76f.pdf