Andrew McGregor

AIS Commentary, July 24, 2017

Canada’s Trudeau government announced last summer that it was prepared to deploy up to 600 troops on a UN peacekeeping mission, likely in Africa. In the meantime, no movement has been made on the pledge, much to the disappointment of the UN and Canada’s allies, who were holding the leadership of the Mali peacekeeping mission open for a Canadian officer. Now, however, a non-UN alternative has emerged, one that is desperately needed and has both a military and development component – the Sahel Group of Five (SG5).

It is perhaps not surprising that no decision has been made regarding a Canadian peacekeeping force in Africa. While Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland speaks of a need for Canada to set a “clear and sovereign course” independent of the United States, both Prime Minister Trudeau and his defence minister Harjit Singh Sajjan have emphasized the importance of consulting Washington before making any decision. Given the Trump administration’s disengagement from Africa and the urgency of a military contribution in Africa, such deference seems unnecessary and counterproductive.

It is perhaps not surprising that no decision has been made regarding a Canadian peacekeeping force in Africa. While Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland speaks of a need for Canada to set a “clear and sovereign course” independent of the United States, both Prime Minister Trudeau and his defence minister Harjit Singh Sajjan have emphasized the importance of consulting Washington before making any decision. Given the Trump administration’s disengagement from Africa and the urgency of a military contribution in Africa, such deference seems unnecessary and counterproductive.

The Purpose of the SG5

In the Sahel, a broad band of arid nations just below the Sahara, political and religious extremism feed off climate change, lack of development, absence of infrastructure, competition for resources and ethnic rivalries, leaving the region in dire need of external assistance and internal reform. Meanwhile, efforts to address these issues are restricted by al-Qaeda and Islamic State terrorism paid for by trafficking in narcotics, migrants and other “commodities.” The region’s barely existent borders make a mockery of unilateral efforts by weak states to address the crime and violence.

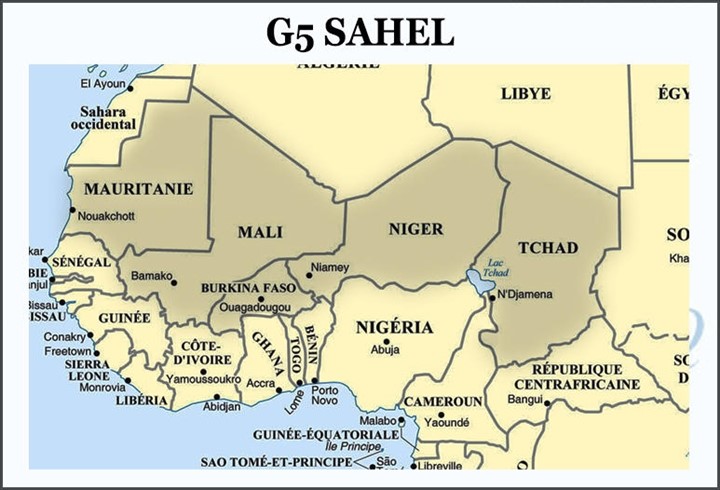

With the encouragement of France, the Sahelian nations of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad and Mauritania created the Sahel Group of Five (SG5) as a multilateral response to these issues in 2014, though the concept remained dormant until its revival last February. While the force’s mandate calls for a campaign against terrorism and trafficking, it also calls for the return of displaced persons, delivery of aid, facilitation of humanitarian operations and a role in implementing development strategies.

Each nation will initially provide a battalion of 750 men aided by French training, communications and logistical support. The military component will operate in all five countries, with the right of “hot pursuit” across international borders. The first military leader of the force will be Malian chief-of-staff General Didier Dacko, an experienced and capable veteran of counter-terrorist and counter-insurgency operations.

The UN Security Council unanimously “welcomed” a resolution calling for the formation of the force on June 21, though US pressure prevented approval for its deployment under a UN mandate, which would have involved UN financing. The Trump administration is seeking to reduce its contribution to UN peacekeeping costs but the US can still be expected to continue providing intelligence and logistical support for counter-terrorist efforts in the Sahel.

The UN Security Council unanimously “welcomed” a resolution calling for the formation of the force on June 21, though US pressure prevented approval for its deployment under a UN mandate, which would have involved UN financing. The Trump administration is seeking to reduce its contribution to UN peacekeeping costs but the US can still be expected to continue providing intelligence and logistical support for counter-terrorist efforts in the Sahel.

Putting the SG5 into action is expected to come with a budget of over €400 million. The EU has pledged €50 million, France €8 million (on top of a substantial military contribution) and each of the SG5 nations will contribute €10 million. France has additionally pledged €200 million in development assistance. Angela Merkel has also promised the support of Germany, which already has 650 troops in Mali and the United Arab Emirates have expressed interest in funding the initiative. The force will seek additional funding from “bilateral and multilateral partners” at a future donors’ conference.

Other than France and Belgium, Canada is the only Western partner with a large military and civil French language capacity, making it ideal for deployment in the francophone Sahel. Canadian contributions in terms of combat troops, logistics, intelligence, training, humanitarian assistance and development planning would greatly reduce the unfunded portion of the SG5’s annual budget while simultaneously improving the capability of all these elements.

Of the contributing Sahel nations, Chad is the most militarily effective, but existing commitments to the UN peacekeeping operation in Mali (MINUSMA) and the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a regional coalition formed to tackle Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin, have forced Chad’s President Idris Déby to warn that substantial assistance will be required for Chad to play its expected role in the SG5. Without Chad’s participation, the alliance stands little chance of battlefield success.

Mali’s government has criticized MINUSMA for its “defensive posture, which has given freedom of movement to terrorist and extremist groups.” The UN’s peacekeepers in Mali have made only glacial progress implementing the terms of the 2015 peace agreement. The force suffers inordinate casualties while doing little to combat terrorism in the region, a task largely left to French troops operating outside of UN auspices. MINUSMA is hampered by the restriction of its operations to territory within Mali’s borders, while its terrorist opponents face no such limits. The SG5 addresses this problem.

As the lone Western sponsor of the SG5 and the former colonial power in each of the participating nations, there is some anxiety that France will exploit the group for its own political and economic benefit. The presence of another less-interested sponsor could provide some balance and reassurance to those African nations already experiencing the strong influence of Paris in their affairs. It might also encourage a more favorable attitude to the force from Algeria, where the bitter legacy of the war for independence has led to great suspicion of all French security efforts in the Sahel.

Not Without Difficulties

Of course participation would not be without problems. A Canadian commitment would have to be long term – creating a capable SG5 could take three years and creating a uniform military standard will be difficult. However, it need not be open-ended; the ultimate goal must always be for the Sahel nations to assume full responsibility.

If funding is limited, security operations will almost certainly be treated as a priority over other aspects of the G5S mandate, based on the harsh reality that violent extremism undermines the effectiveness of all other programs as well as the sovereignty of regional states. At present, aid workers are regarded by the region’s militant groups as nothing more than easy prey and a source of funding through ransom.

Integration of alienated groups into security and development operations will be essential if the SG5 is to be prevented from becoming a transnational occupation force. This cannot be achieved without offering economic alternatives to rebellion and cross-border crime, emphasizing the importance of the development component.

Despite fears that France may be looking to draw down their African commitment, President Emmanuel Macron has pledged continued French support and has already visited the region twice to confirm this commitment. There is no doubt, however, that Paris is seeking to reduce its military expenditure in Africa – Operation Barkhane, its 4,000 man mission to provide security in the Sahara/Sahel region, costs €800 million per year.

Despite fears that France may be looking to draw down their African commitment, President Emmanuel Macron has pledged continued French support and has already visited the region twice to confirm this commitment. There is no doubt, however, that Paris is seeking to reduce its military expenditure in Africa – Operation Barkhane, its 4,000 man mission to provide security in the Sahara/Sahel region, costs €800 million per year.

Conclusion

A religious adherence to UN peacekeeping as the only legitimate or desirable means of contributing to international security turns a blind eye to less rigid and more adaptive structures free of UN bureaucracy and inefficiency.

For a Canadian government increasingly seen as soft on terrorism, unwilling to rescue or ransom its Canadian victims but eager to reward Canadian-born practitioners, the need for some sort of dedication to international counter-terrorism efforts might seem obvious. The SG5 provides an opportunity for Canada to stand beside its European allies, set an independent course from Washington and play a meaningful role in destroying Africa’s deadliest extremist groups while engaging in important development assistance where it is needed most.

If Ottawa’s aim in African security operations is to encounter minimal difficulties and avoid casualties, the SG5 will not be for them. If, however, Canada is ready to give its highly capable military and development sector a real challenge with the potential of providing a secure future to some of the world’s most impoverished peoples, then it should take a serious look at the SG5 alternative.

According to Foreign Minister Freeland, “it is precisely the countries that stand for values and human rights that also need to be ready to say we are prepared to use hard power where necessary.” If the world “needs more Canada,” the Sahel is in special need of a Canadian presence.

Dr. Andrew McGregor is the Director of Aberfoyle International Security, a Toronto-based agency specializing in security issues in the African and Islamic worlds.