Andrew McGregor

Military History, March 1, 2018

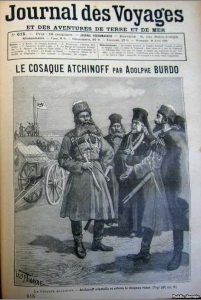

Freebooter Nikolai Ashinov sought a foothold for Mother Russia in the Red Sea – but his African misadventure only caused embarrassment.

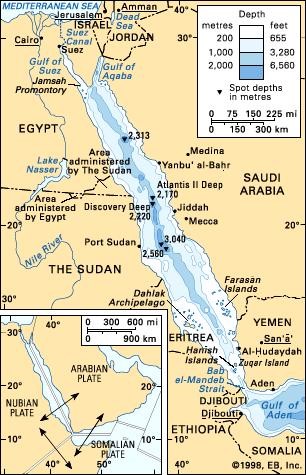

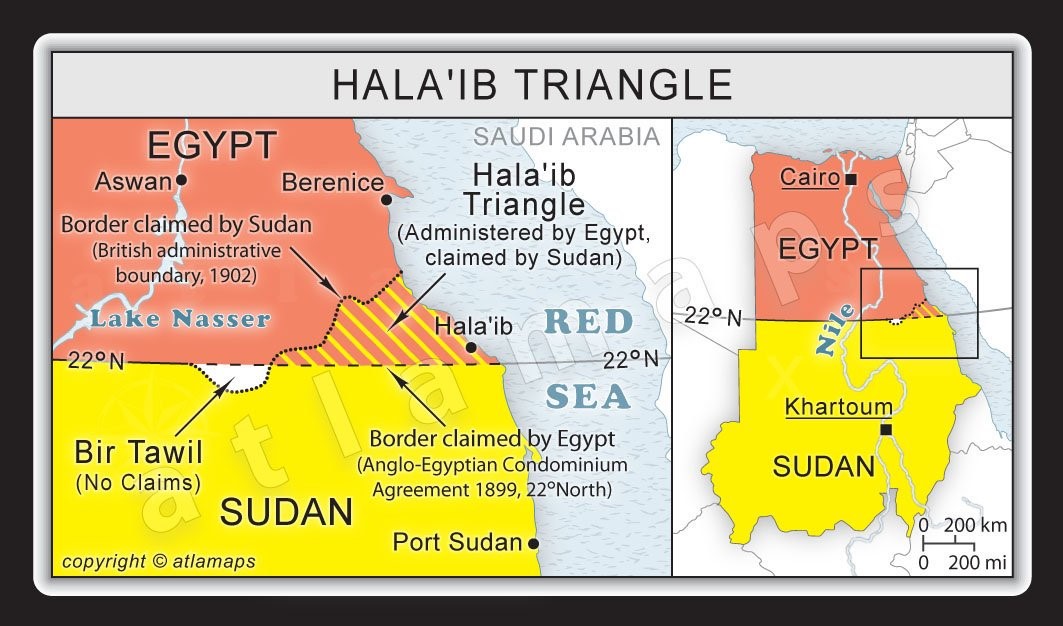

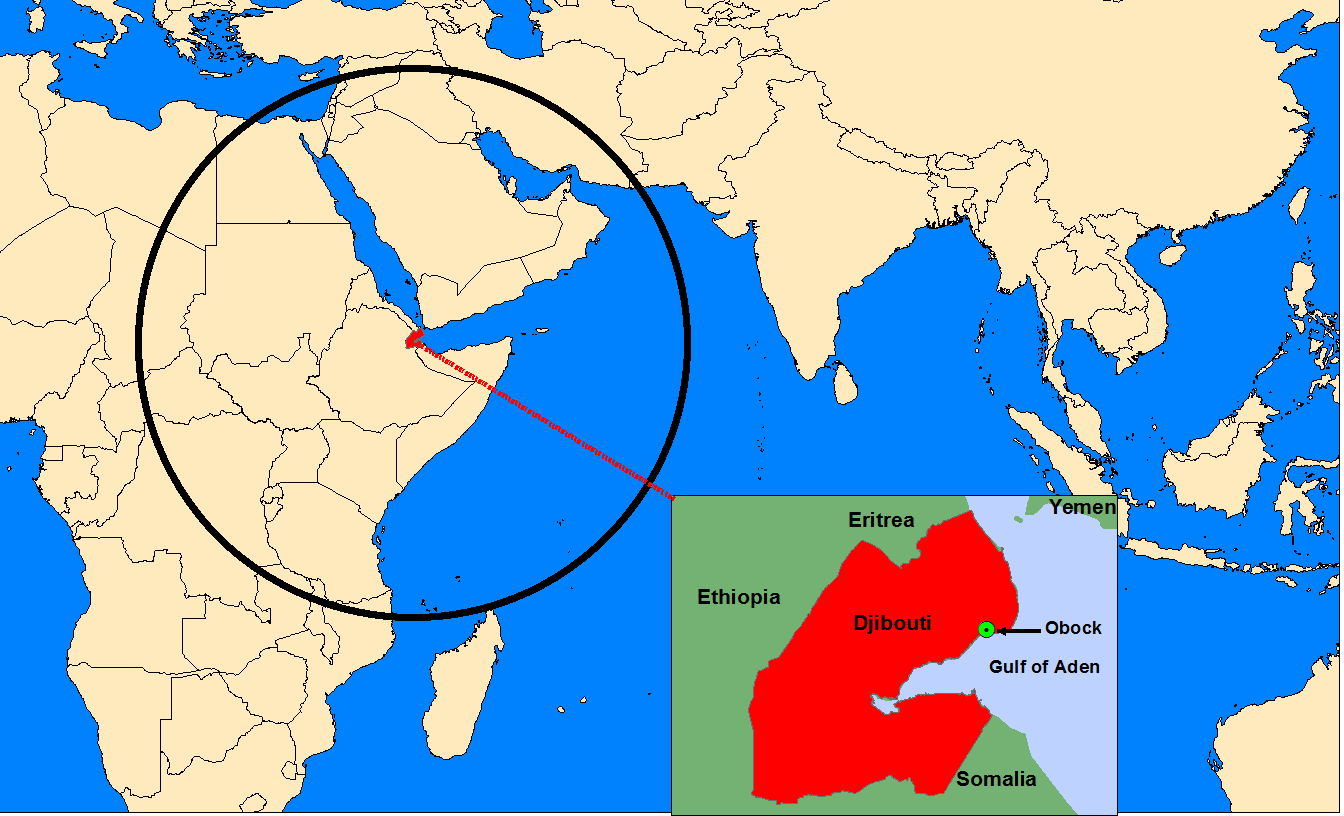

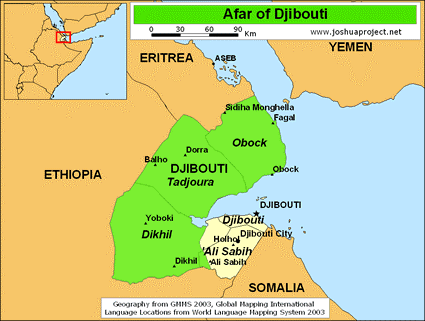

Imperial Russia’s 19th century struggle with the British Empire for control of Central Asia left it out of the division of Africa and its resources by the other European powers. However, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 focused the attention of some Russians on establishing a warm water port that would control access to the Red Sea’s southern entrance in the region now known as Djibouti. However, Russia’s Foreign Ministry had little interest in a Russian expansion to Africa, leaving its execution to an unlikely and roguish adventurer, Nikolai Ivanovich Ashinov (1856 – 1902), a member of the Terek Cossack Host of the Chechen lowlands.

Though poorly educated, the determined Ashinov possessed enough energy to attract support for the establishment of a Russian base that would offer an entry point to Christian Ethiopia while overseeing the shipping lanes that transported India’s wealth to Britain. Ashinov, however, had failed to notice one vital detail – his projected base in Tadjura (northern Djibouti) was already claimed by France. Joined by an unlikely force of Cossack warriors and Russian Orthodox priests, Ashinov’s attempted occupation of an abandoned fort there in 1889 led to what Tsar Alexander III described as “a sad and stupid comedy” that ignited an international crisis.

Ethiopia barely registered on the Russian consciousness until 1847, when Lt. Colonel Igor Petrovich Kovalevsky led a two-year Russian expedition from Cairo up the Blue Nile into eastern Gojam (north-west Ethiopia) in search for gold deposits. A year later, Russian monk Porfiry Ouspenski claimed (incorrectly) that the rites of the Russian and Ethiopian Orthodox churches were nearly identical after meeting Ethiopian monks in Jerusalem. He suggested sending a religious mission to the Ethiopian emperor in order to unite the churches with the ultimate goal of sending Orthodox missionaries (and Russian influence) to Sudan, Darfur and Somalia. Nothing came of the plan, but in 1855, Ethiopian emperor Tewodros II sent a letter to the Tsar suggesting a joint effort to wrest Jerusalem from Ottoman control. The timing was bad, with Russia just having suffered defeat in the Crimean War.

Meanwhile, the French were taking interest in the physically challenging Gulf of Tadjura region. In 1856, Henri Lambert, the French Consul in Aden, became the first European to visit the Gulf port of Obock and negotiated trading rights with the local Sultan. Lambert was murdered three years later after inserting himself into a local political dispute, but a treaty of alliance was signed by the Sultan of the Danakil in 1862 and Obock purchased for French use. The French found little use for Obock at first and even considered selling it to the Egyptians, who were expanding their African Empire with a modernized military heavily reliant on Western mercenaries, including many veterans of the American Civil War. In 1874 Egyptian troops began occupying the coast southwards from Tadjura. By 1882 French ships observed Egyptian forces moving into the French holdings in the Gulf region. French interest in the area grew the next year after French naval ships were refused re-coaling in the British-held port of Aden for the second time in 13 years. By now the Egyptian military presence was pervasive in Obock, which France had still made no effort to occupy.

The Ethiopian destruction of the Egyptian Army at the Battle of Gura in March 1876 was the beginning of the end of Egypt’s efforts to expand its influence in the Horn of Africa. By 1884 they agreed to abandon their bases along the Ethiopian and Somali coasts, a withdrawal several European powers were ready to exploit. France despatched the energetic Léonce Lagarde, Count of Rouffeyroux, to take care of its interests in the region. Fresh from colonial service in Cochin-China and Senegal, Lagarde established himself on the south side of the Tadjura Gulf before expanding French rule into the rest of the region, building the basis for an eventual French colony. Though the Italians and British were successful in occupying some of the abandoned Egyptian garrisons, Lagarde beat Royal Navy warships to Tadjura by only a few hours, adding the area to the newly established French protectorate by agreement with the local Sultan. The territory included the old fort of Sagallo. Evacuated by the Egyptian garrison, the decaying fort was temporarily occupied by French troops from the cruiser Seignelay.

The Bay at Sagallo by German landscape artist Johann Martin Bernatz (1802-78)

The Bay at Sagallo by German landscape artist Johann Martin Bernatz (1802-78)

Ashinov began his career in the caravan trade to Persia and Turkey before volunteering for service in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, in which large numbers of the Terek Host fought on the Balkan and Caucasus fronts. Ashinov claimed to be an ataman, or Cossack leader, but others denounced him as an imposter. During a visit to Constantinople, Ashinov encountered two Circassian Muslims returning to the North Caucasus from Egypt who told him of a fertile land to the south of Egypt whose inhabitants practiced an ancient form of Christianity.

The Gulf of Tadjura

Ashinov’s first trip to Africa was in 1885, landing at the Red Sea port of Massawa, which Italy had only just occupied as Egypt’s rule in the region collapsed. The Cossack quarrelled with the Italians (who were also attempting to assert control over Ethiopia) before heading inland. Though accounts differ on whether Ethiopian emperor Yohannes IV met with Ashinov or not, the Cossack claimed to have obtained a geographically vague permit to create a Cossack settlement on the Gulf of Tadjura. He met Ras Alula, an Ethiopian general and one of the most important figures on the Red Sea coast, and made a reconnaissance of Tadjura, where French poet turned gunrunner Arthur Rimbaud ran arms to local warlords.

To a large degree Ashinov was a product of Russian Slavophilism, an intellectual movement grounded in traditional Russian culture. It emphasized the role of the Orthodox Church, rejected Westernism and sought further expansion of the Russian Empire into new territories. Ethiopia and the Red Sea coast caught the eye of the expansionists, attracted by the region’s strategic value and Ethiopia’s Orthodox Church, which seemed to offer some common ground between the two nations. The preferred base for such efforts, the Gulf of Tadjura, was claimed but not yet fully consolidated by the French. Nonetheless, leading merchants and administrators (including the Tsar’s brother) began to line up behind Ashinov in the hope that when the Cossack colony became a reality, the Tsar would step in and make it an official Russian overseas territory. Despite concerns about Ashinov’s character, Alexander III appears to have toyed with the idea in the face of protests from the Russian Foreign Ministry, which was attempting to cultivate France as an ally. In the end, the Tsar neither supported nor prevented the African initiative, preferring to see how events unfolded.

Ashinov failed to raise support in Paris in 1887 by selling his idea as a joint Russo-French venture, but a lack of overt opposition may have convinced him that he had the tacit support of both France and Russia. Ashinov returned to Tadjura in 1888, where he collected two Ethiopian priests sent by Yohannes to attend the 900th anniversary of the Russian Orthodox Church. Ashinov brought the priests to celebrations in Kiev and then St. Petersburg. They met the Tsar at the insistence of Alexander’s leading advisor, who informed Alexander, “In such enterprises the most convenient tools are cutthroats of the likes of Ashinov.”

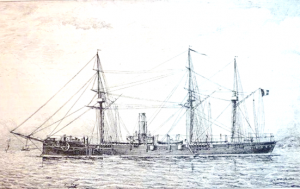

Russian Gunboat Mandjur

Depending upon whose backing was being sought, Ashinov represented a Russian mission to Tadjura as strategic, commercial or religious in intent. Russian scholars began to produce detailed analyses of the Tadjura region, but Ashinov’s project was vigorously opposed by the Foreign Ministry, which did not care to put Russia’s international relations in the hands of a rogue Cossack. Nonetheless, support was found, including that of Russian naval commander Admiral Ivan Shestakov, who sent the Russian gunboat Mandjur to Aden to support the Cossacks. Unfortunately for Ashinov, the ship was recalled after the admiral’s sudden death in December 1888.

As part of its religious cover, the mission was joined by Father Païsi, an Archimandrite of the Orthodox Church. Païsi, formerly a monk at Mount Athos in Greece, was also an Orenburg Cossack with military experience in Central Asia. A popular figure in Russia, Païsi, as official head of the mission, gave it credibility and popularity at home.

With roughly 150 armed men of the Terek Cossack Host and a number of monks, women and children, the mission left Odessa on December 10, 1888 and landed at Tadjura on January 18, 1889 after taking a circuitous route on three different ships to avoid observation. The last ship, the Austrian Amphitrite, was followed through the Suez Canal by the Italian gunboat Agostino Barbarigo before slipping the Cossacks past a patrolling French sloop, the Météore.

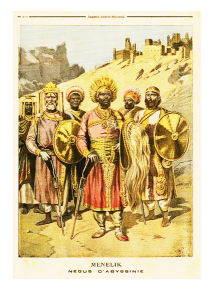

Emperor Menelik II of Abyssinia

Once ashore, the pretense of a religious mission to Ethiopia was quickly abandoned as Ashinov revealed his intention to settle permanently in the Gulf of Tadjura. Italian protests that it had sovereignty over Ethiopia were largely ignored by Russia, which had never recognized the Italian claims. Emperor Menelik II, who had succeeded Yohannes after the latter was killed by Mahdists at the Battle of Gallabat, was surprised to learn of the Italian claim to his realm, but believed an Italian envoy’s assertions that Italy had no designs on Ethiopia. The Italian press began describing the Cossacks in the worst light possible – Ashinov was uneducated, a pirate and a rapist, while his wife Sofia Ivanovna, a highly educated woman who had accompanied Ashinov, was a hysterical individual and the real leader of the expedition.

Meanwhile, Commandant Lagarde dispatched an officer from the Météore to warn Ashinov and his men that any abuse of the local Danakil population would be met with a harsh response. Ashinov’s group settled into the abandoned Egyptian fort at Sagallo on January 28. Renaming the position “New Moscow,” the Cossacks fashioned a makeshift chapel (“The Church of St. Nicholas”) and raised a specially designed flag in which the Russian white, blue and red tricolor was overlaid with a yellow Saltire cross. Four of the Russian monks were former Russian military engineers who had joined the clergy to escape some type of scandal; these individuals were responsible for building any necessary fortifications. Ashinov, Païsi, and the handful of Cossack families took refuge in the fort’s blockhouse while the rest used temporary shelters outdoors. Even though it was “winter,” a daily average high temperature of 84˚ F under a relentless sun made the work of rebuilding the fort a taxing effort for the northern intruders. Discipline dissolved quickly and Ashinov was forced to distribute cash to his followers to dissuade them from raiding passing caravans.

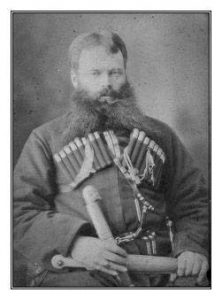

Ashinov, Father Paiisi and others at Fort Sagallo

Ashinov, Father Paiisi and others at Fort Sagallo

The colonial ambitions of Italy and Britain were threatened by the possibility of Russian arms being delivered directly to indigenous groups in Africa. France was thus urged to assert its claims in the Tadjura region and bring a quick end to the Cossack occupation. The problem was that France was not necessarily hostile to the Russian incursion and was ready to consider the usefulness of cooperative efforts in the Horn region to interrupt Britain’s dominance of the approaches to the Suez Canal, purchased by Britain in 1875.

The French and Cossacks engaged in a brief propaganda war, with Ashinov trying to convince the Danakil that the French were but a minor power while Lagarde gave the tribesmen the impression that the Russians were only there with French permission. Lagarde sent emissaries to Ashinov to demand he turn over his group’s “excess weapons,” lower his flag and raise the French flag. None of this was done, Ashinov claiming he could do nothing without the permission of the local ruler, Muhammad Leita, who was conveniently away fighting the Somalis. Never a diplomat, Ashinov failed to recognize he was being offered an opportunity to remain so long as he observed certain formalities.

Eventually the Cossacks began raiding the Danakil, stealing their animals and raping their young women. All the noble religious rhetoric surrounding the purpose of the expedition came crashing down. Not all the Cossacks were pleased with the chaotic conditions and lack of leadership. Some deserters were caught by the Danakil and turned over to the French in Obock, where they were able to give a true picture of the disorder prevailing in “New Moscow.” Angered that Ashinov was discrediting Russia abroad, Tsar Alexander publicly disavowed any involvement with Ashinov’s mission.

Once the French government was satisfied that Ashinov’s expedition had no official backing in Russia, orders were delivered to Admiral Orly, commander of the French Levant squadron, to expel the intruders. The cruisers Primauguet and Seignelay steamed for Tadjura, picking up Governor Lagarde at Obock, where they were joined by the gunboats Météore and Pingouin.

By now, the Tsar was heeding the counsel of the Foreign Ministry and demanded that “this beast Ashinov” be removed from Tadjura as soon as possible. After Paris learned that the Russians had decided to send the gunboat Manchuria from Aden to deal with Ashinov themselves, orders were sent to Orly’s squadron to stand down. Due to the poor communications of the day the new orders were not received in time.

On February 5, 1889 the French cruisers arrived offshore. An officer was sent to bring Ashinov to his senses, if the sight of the warships lining up in battle formation had not already done so. Some 20 Cossacks understood the implications and swam out to the French ships to surrender. The French lieutenant informed Ashinov that Lagarde wished to see him on board immediately. Ashinov replied that he didn’t especially feel like going anywhere at the moment, but helpfully suggested that if Lagarde really wanted to speak to him, he could come to the fort.

Panic gripped the Russians when the French naval guns opened a fifteen-minute barrage. Ashinov ordered some of the Cossacks to create a line of defense on the beach, but this suicidal command was ignored. Though eleven larger shells were fired, most of the French fire came from the newly introduced 47 mm rapid-firing Hotchkiss cannon. Cossack skill in arms and horsemanship provided no defense for naval guns, and the group had little alternative but to run for the nearby woods or hide behind the fort’s ruined walls and pray.

By the time the shelling was over, two women, three children and one Cossack were dead, with 22 more wounded. The women and children had taken refuge in the fort’s main building, a useful target for the French guns. The fight had been pounded out of the Russians, who were now more than ready to surrender. The survivors began to carry the wounded down to the beach. The Ataman’s arrogance had taken a shocking beating, and it was left to Father Païsi to deal with the French, Ashinov’s wife serving as interpreter. Païsi angrily protested the French action but found little sympathy; French opinion was that the Cossacks had brought it on themselves after passing up numerous opportunities to stand down.

French troops collected all the Russian weapons and oversaw the embarkation of the Russians to Obock. To prevent any re-occupation of the site, Admiral Orly ordered the remaining fortifications to be destroyed with explosives. After transport to Suez, the surviving Cossacks were put aboard the Russian cruiser Zabiyaka on March 4 for a depressing trip back to the naval base at Sebastopol, though some sources indicate that four monks were allowed to proceed on a “religious mission” to the Ethiopian court.

Ashinov found himself treated like a bad odor back in Russia. Given the Tsar’s anger with him, Ashinov was perhaps lucky to be punished with only three years exile in the Volga River region; the Foreign Ministry had recommended five years in Siberia. The Cossack tried to flee to Paris and London, but eventually obeyed an order from the Tsar to return home in 1891. His new sentence was ten years’ exile to his wife’s estates in Chertigov in the northern Ukraine. After this, his trail grows cold, though one account claims Ashinov flourished in Chertigov as late as 1906. Ashinov’s antagonist, Commandant Lagarde, went on to become French ambassador to Ethiopia and was made Duke of Entotto by Menelik in 1897.

Even as Ashinov was engaged in his failed effort to create an African “New Moscow,” the Russian Minister of War was busy developing his own mission to the Ethiopian court using a trusted and far less erratic officer, Lieutenant Vasiliev Federovich Mashkov, an Anglophobe and strategic thinker. In October 1889, Mashkov arrived in the court of Menilek II with the apparent support of Lagarde. French and Russian interests were converging so far as challenging British control of the sea routes passing the Horn of Africa. Mashkov’s second visit in 1891 led to the eventual formation of a Russian military advisory mission and the delivery of Russian arms that helped Menelik defeat the Italian Army at Adowa in 1896. France and Russia viewed Italy as an ally of Britain in the contest for the Horn.

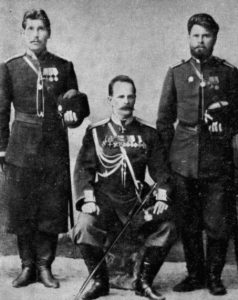

Nikolai Leontiev

Captain A.V. Eliseev visited Tadjura and the nearby Sultanate of Rahayta in 1895 with an eye to establishing relations. Eliseev was accompanied by a representative of the Russian Orthodox Church as the idea of uniting the Russian and Ethiopian churches persisted to the end of the 19th century. The Cossack connection continued as Eliseev’s visit was followed up by Kuban Cossack Captain N.V. Leontiev (who alarmed the British with his plans to contact the Mahdist regime in Omdurman) and a mission led by Colonel Leonid Artamonov, who became military advisor to Menelik II.

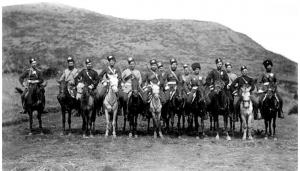

Artamanov with Cossacks Shedrov and Archipov

Artamanov with Cossacks Shedrov and Archipov

Artamanov and two Cossack soldiers accompanied the military expedition of Ethiopian commander Tessema Nadew to the White Nile in 1898 in advance of both Kitchener’s British forces and the French Marchand expedition, but the diseased and exhausted Ethiopians were compelled to withdraw after raising the Ethiopian flag near Fashoda. In the same year, Russia established formal relations with Ethiopia and built an impressive embassy in Addis Ababa, guarded by forty Cossacks. France meanwhile consolidated its territories and protectorates in the Tadjura Gulf region in 1896 as the Côte française des Somalis.

In the end, the Ashinov adventure failed to cause a breach in the warming Franco-Russian relations. In the face of growing British might, no mere Cossack could significantly influence geo-political imperatives. Russia had suffered an embarrassment, but France had suffered little – if anything, its local prestige in the Horn had been raised by the firmness with which it had dealt with the Russian challenge.

Despite Russian attempts to become a player in the Horn, its inability to establish a permanent presence on the coast was to have devastating consequences in 1905, when Japan’s devastation of Russia’s Pacific Squadron at Port Arthur forced Russia to send its outdated Baltic Fleet to tackle Admiral Tojo’s British-built battleships. London denied use of the Suez Canal after the Russians fired on British fishing boats in the North Sea, mistaking the trawlers for Japanese torpedo boats. After an 18,000-mile journey round the Cape of Good Hope, the exhausted Russian fleet was destroyed by the Japanese at the Battle of Tsushima. Ashinov and his backers had grasped the strategic importance of a Russian base in the Horn of Africa, but the Cossack’s erratic behavior unwittingly contributed instead to Imperial Russia’s military decline.

Dr. Andrew McGregor is director of Aberfoyle International Security and writes on military, security and terrorism issues. For further reading he recommends The Russians in Ethiopia: An Essay in Futility, by Czeslaw Jesman, and Russia and Black Africa before World War II by Edward Thomas Wilson.

This article first appeared as “The Half-Cocked Cossack: Nikolai Ivanovich Ashinov and the Russian Occupation of Djibouti, 1889,” Military History 34(6), March 2018, pp. 32-39.