Andrew McGregor

June 26, 2014

In some ways, the recent triumphs of the radical Sunni Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) inside Iraq have alarmed Riyadh as much as Tehran. While the Saudis are still willing to support less radical Islamist movements in Syria and Iraq as part of a proxy war against Shiite Iran, there are fears in Riyadh that ISIS extremists, many of whom were recruited in Saudi Arabia, may eventually turn their attention to the Kingdom itself, threatening its hereditary rulers and the stability of the Gulf region. Iraq and Iran, meanwhile, accuse the Saudis of sponsoring terrorism and religious extremism throughout the Middle East.

Iraqi president Nuri al-Maliki first accused Saudi Arabia of financing Iraqi terrorists in March. Echoing al-Maliki, the Shiite-dominated Iraqi cabinet issued a statement on June 17 in which they held the Saudis “responsible for supporting these [militant] groups financially and morally… [and for] crimes that may qualify as genocide: the spilling of Iraqi blood and the destruction of Iraqi state institutions and religious sites” (Arabianbusiness.com, June 17). Saudi Arabia reacted to the allegations by releasing a statement condemning ISIS as well as the Iraqi government:

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia wishes to see the defeat and destruction of all al-Qaeda networks and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) operating in Iraq. Saudi Arabia does not provide either moral or financial support to ISIS or any terrorist networks. Any suggestion to the contrary, is a malicious falsehood. Despite the false allegations of the Iraqi Ministerial Cabinet, whose exclusionary policies have fomented this current crisis, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia supports the preservation of Iraq’s sovereignty, its unity and territorial integrity (Arab News [Jeddah], June 19).

The Iranian press has clearly stated the Kingdom is the largest sponsor of terrorism in the region (Javan [Tehran], June 14). Tehran considers Riyadh to be in complete support of efforts to drive Iraq’s Shi’a majority from the central government in Baghdad. After Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani announced Iran’s readiness to defend Shi’a holy sites in Iraq, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, Prince Sa’ud al-Faisal, warned against foreign interference in Iraq. While also pledging fighters to defend the Shi’a shrines of Iraq, Hezbollah secretary general Hassan Nasrallah was less eager to accuse the Saudis of directly sponsoring the radical Salafist ISIS movement, saying only: “It is uncertain that Saudi Arabia had a role” (Ra’y al-Yawm, June 17).

Prince Sa’ud al-Faisal (Reuters)

Syria has also pointed to Saudi Arabian responsibility for arming and funding ISIS operations in that country at the behest of Israel and the United States and in cooperation with Qatar and Turkey. According to Syrian state media: “No Western country is unaware of the role Saudi Arabia is playing in supporting terrorism and funding and arming different fronts and battles, both inside and outside Iraq and Syria” (al-Thawra [Damascus], June 12).

Saudi Grand Mufti Shaykh Abd al-Aziz Al al-Shaykh denounced ISIS on May 27, condemning their recruitment of Saudi youth for the war in Syria (al-Riyadh, May 27). The Kingdom has also stepped up its terrorist prosecutions, diving into a backlog of hundreds of cases mainly related to the 2003-2006 Islamist insurgency. Sentences of up to 30 years in prison are being issued in cases where there once seemed little inclination to prosecute (Saudi Press Agency, June 10). Earlier this year, King Abdullah issued decrees prohibiting Saudi citizens from joining the jihad in Syria or providing financial support to extremists.

Saudi foreign minister Prince Sa’ud al-Faisal recently told an Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) gathering in Jeddah that Iraqi claims of Saudi support for terrorism were “baseless,” but warned there were signs of an impending civil war in Iraq, a war whose implications for the region “cannot be fathomed” (Arabianbusiness.com, June 18; al-Arabiya, June 19). The Saudi government has blamed “the sectarian and exclusionary policies implemented in Iraq over the past years that threatened its stability and sovereignty” (al-Akhbar [Beirut], June 10). Officially, Saudi Arabia disavows sectarianism in Iraq and calls for a unified Iraqi nation with all citizens on an equal basis without distinction or discrimination (al-Riyadh, June 18).

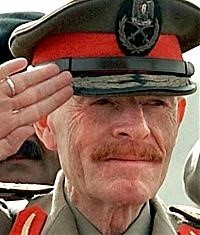

Prince Turki al-Faisal

Saudi authorities hold the Maliki government responsible for the present crisis and its sometimes bewildering implications, a stance summed up by former Saudi intelligence chief Prince Turki al-Faisal:

Baghdad has failed to stop the closing of ranks of extremists and Ba’thists from the era of Saddam Hussein… The situation in al-Anbar in Iraq has been boiling for some time. It seemed that the Iraqi government not only failed to do enough to calm this situation, but that it pushed things towards an explosion in some cases… One of the possible ironies is to see the Iranian Revolutionary Guard fighting alongside U.S. drones to kill Iraqis. This is something that makes a person lose his mind and makes one wonder: Where are we headed? (al-Quds al-Arabi, June 15; Arab News, June 14).

When Prince Bandar bin Sultan was removed from his post in April and replaced by Prince Muhammad bin Nayef it was interpreted as a sign Riyadh was prepared to vary from the hardline approach to Iran taken by the ex-intelligence chief (Gulf News [Dubai], May 21). The change reflects the Saudi government’s appreciation of the strategic situation it finds itself in as Washington shows greater reluctance to intervene directly in the affairs of the region. The lack of American consultation with the Kingdom during initial U.S.-Iranian discussions has convinced many in Riyadh that their nation must forge its own relationship with Iran to avoid a wave of conflict that could threaten the traditional Arab kingdoms of the Gulf region. The election of new Iranian president Hassan Rouhani has presented new possibilities in the Saudi-Iranian relationship, including a common approach to Turkey, whose Islamist government has supported the Muslim Brotherhood, now defined as a destabilizing threat in both Iran and Saudi Arabia. However, this remains conjecture at this point, as Riyadh follows a cautious approach to an Iranian rapprochement. While improved relations might prove beneficial, the Kingdom cannot afford to risk its self-adopted role as the guardian of Sunni Islam.

The rapprochement with Iran began tentatively earlier this year, with a series of secret meetings in Muscat and Kuwait followed by more official encounters between the Saudi and Iranian foreign ministers (National [Abu Dhabi], May 19). Diplomacy between the two nations appears to have been spurred by American urgings and the Kingdom’s realization that a reactive rather than pro-active foreign policy could leave the Saudis outside of a recalibrated power structure in the Middle East. There are fears in Riyadh that ISIS offensive may result in Iranian troops joining the fight against Sunni extremists in Iraq, followed by the breakup of the country (al-Quds al-Arabi, June 15).

While Saudi Arabia appears to have backed off from its covert financial support of ISIS, private donations likely continue to flow from donors in the Kingdom and other Gulf states, though the recent looting of bank vaults and consolidation of oil-producing regions in Syria and Iraq mean that ISIS will be largely self-supporting from this point. Saudi anxieties over political change in the Middle East are reflected in the Kingdom’s growing defense budget, which now makes the nation of under 30 million people one of the world’s top six military spenders (Arabianbusiness.com, June 14).

This article was first published in the June 26, 2014 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.