Andrew McGregor

May 31, 2011

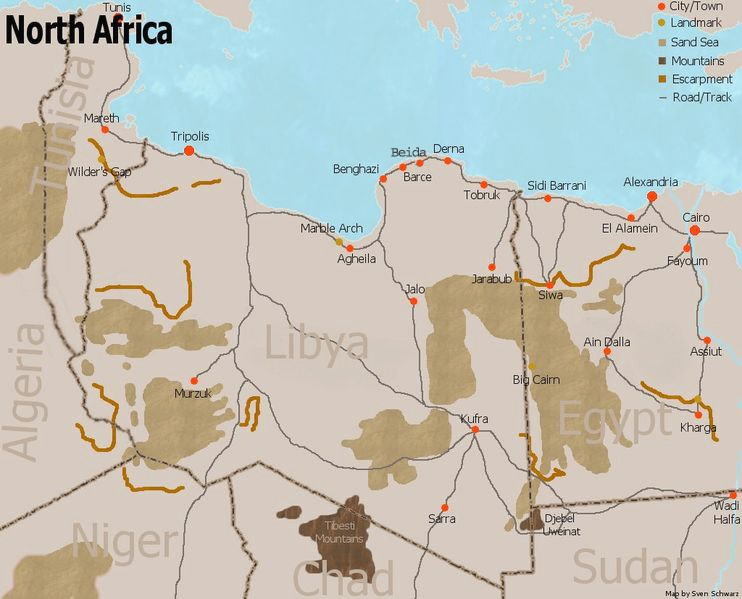

In the aftermath of the successful vote for independence, South Sudan’s government now finds itself faced with several rebel militias, tribal violence and clashes between gunmen in oil-rich Jonglei state, South Sudan’s largest. Prominent among the rebel generals threatening the unity of South Sudan as it approaches full independence in July is Major General Gabriel Tang (a.k.a. Gabriel Gatwich Chan Tanginya, i.e. “Long Pipe”), aNuer tribesman from Jonglei’s Fangak county. Though he began his career as a separatist rebel, General Tang has long been known as a Khartoum loyalist. Today General Tang is a Southern warlord of uncertain loyalties following a recent series of professions of loyalty to the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) interspersed with a series of armed revolts carried out by his followers, the Tangginyang. General Tang’s future direction will play a crucial role in the development of South Sudan’s massive oil potential, its only important source of revenue and the key to the incipient nation’s success.

Major General Gabriel Tang

Gabriel Tang Joins the Anyanya I Rebellion

Gabriel Tang began his career by taking up arms as a youth in the Anyanya separatist rebellion (1955-1972) that broke out in South Sudan after a number of Southern garrisons mutinied in the lead-up to Sudanese independence in 1956. [1] Under the terms of the 1972 Addis Ababa Peace Agreement, most of the Anyanya rebels were absorbed into the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), but many others rejected integration, some finding employment in the Ugandan Army of Idi Amin. Tang rejected integration and remained in the Upper Nile district until he joined one of a number of dissident militias operating in the South under the umbrella term “Anyanya II.”

The SPLA and Anyanya II

Tang’s differences with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) and its late leader Colonel John Garang date back to 1983-84, when the Anyanya II movement came into conflict with the newly-formed SPLA which had renewed the rebellion against Khartoum. Many in the Nuer militias of Anyanya II rejected what they viewed as a Dinka-dominated SPLA leadership.

By 1984, Khartoum began to exploit these divisions, providing arms and funds to a more formally organized “Anyanya II” under the leadership of Nuer leaders such as William Abdullah Chuol and Paulino Matip Nhial. The hope was that this militia would help secure the oil fields of Jonglei, but as the Anyanya II enjoyed only limited support amongst the Nuer, the result was a bitter conflict between Nuer militia members and Nuer forces under the SPLA banner. [2] The Anyanya II were successful in disrupting SPLA supply routes and attacking columns of SPLA recruits headed to Ethiopia for training, but by 1988 most of the movement had decided to join the SPLA. Those remaining hostile to the SPLA, including Gabriel Tang, began to be more closely integrated with Sudan’s military intelligence and regular army.

Rivalry with the SPLA during the Second Civil War

The SPLA suffered a devastating split in 1991 when three senior commanders, Riek Machar, Gordon Kong Chuol and Lam Akol, announced the overthrow of John Garang as the movement’s leader. In practice, however, Garang remained in the field with substantial forces under his command and the following decade witnessed a brutal civil war within a civil war between Garang’s SPLA-Mainstream (a.k.a. SPLA-Torit) and Riek Machar’s SPLA-Nasir faction. As Riek Machar’s pro-Khartoum tendencies became clearer (they were eventually sealed in a 1998 agreement with Khartoum), SPLA-Nasir began to splinter and once again there were numerous clashes between different Nuer factions.

Following Riek Machar’s 1998 agreement with Khartoum, his forces were renamed the United Democratic Salvation Front/South Sudan Defense Force (UDSF/SSDF). A clear Khartoum loyalist by now, Tang became a leading commander in the SSDF with a close association to the SAF. After the 1998 agreement, SSDF figures such as Riek Machar and Gabriel Tang were commonly seen in Khartoum. Even after Machar’s 2002 reconciliation with John Garang and SPLA-Mainstream, Tang remained a pro-government militia leader. The SSDF became so closely identified with Northern interests that it was not allowed to be an independent party to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) talks on the grounds the movement had become synonymous with Khartoum.

2004 Campaign against the Shilluk in Upper Nile

General Tang’s most notorious campaign took place in the Shilluk tribal lands of the Upper Nile in 2004. The origin of the violence dated back to 1991, when Shilluk leader Dr. Lam Akol broke away from the SPLA to form the ironically-named SPLA-United. Fighting between the SPLA and the breakaway group continued until the Fashoda Peace Agreement of 1997 landed Lam Akol’s movement firmly in the pro-Khartoum camp. When Akol rejoined the mainstream SPLA in August 2003, Khartoum took steps to bring the Shilluk country in Upper Nile back under government control. Pro-Khartoum Shilluk militias were joined by SAF gunboats and pro-Khartoum Nuer militias under the leadership of General Tang, General Paulino Matip and Tang’s lieutenant, Thomas Mabor Dhol in an offensive along the west banks of the Nile and Bahr al-Ghazal rivers, attacking the village of the Shilluk king, among others. Shilluk communities were devastated with large loss of civilian life and tens of thousands displaced (Sudan Vision, March 13; IRIN, March 13, 2004). Tang’s efforts were rewarded with a promotion to Major General in the SAF.

A Three Day Battle in Malakal

When many Nuer leaders of pro-Khartoum militias went over to the SPLA in 2006 after signing onto the Juba Declaration, Tang remained in the Khartoum camp, unwilling to associate with the Dinka commanders in the SPLA that he believed intended the subjugation of the Nuer.

After a dispute between the SPLA and the Tangginiya, shooting broke out in Malakal (capital of Upper Nile state) with both sides claiming the other had fired first. The SSDF accused Salva Kiir and Riek Machar of engineering an “assassination attempt” on “SSDF Chief of Operations, Major General Tang” that began with an assault on Tang’s Malakal residence (SSUDA-SSDF Press Release, March 29, 2009). The dispute turned into a pitched battle, with Tang’s force falling back on a barracks close to the Malakal airport (Reuters, December 2, 2006).

After three days of fighting and looting that had scattered bodies in the streets and left Malakal without a water supply, GoSS president Salva Kiir cut short an official visit to Uganda to return to South Sudan (New Vision [Kampala], December 1). Malakal residents began to draw water directly from the Nile, which was contaminated with dead bodies, furthering a local outbreak of cholera (Reuters, December 2, 2006). Leaving thousands of local residents displaced or in mourning, General Tang returned to the safety of Khartoum.

Collapse of the Joint Integrated Units in Malakal

Under the terms of the 2005 CPA, Tang had the option of aligning his men with either Khartoum’s SAF or the Southern SPLA. After opting for the former, Khartoum decided to send Tang’s fighters south as part of the Northern component of the newly formed Joint Integrated Units (JIU). Given Tang’s history in the region, Khartoum’s decision to deploy Tang in his regional home capital of Malakal could be described as somewhere between mischievous and provocative.