Andrew McGregor

When Mauritania’s President Mohamed Ould Abd al-Aziz identified political Islamists as extremists and national enemies of Mauritania last August, his bluntness surprised some observers: “Proponents of political Islam are all extremists… Islamists, who practice politics and wear ties, can take up arms if they cannot achieve their goals via politics” (Saudi Gazette, August 31).

Faced with what authorities believe is religious and political interference in Mauritania by Iran and Qatar and the threat posed by jihadists lurking along the border with Mali, the president has undertaken several steps to scale back Islamist activities in Mauritania, including the closing of Islamic universities and moving towards a ban on the Muslim Brotherhood. Mauritanian troops are also now operating with the French-backed Sahel Group of Five (G5S – a regional security and development alliance that includes Mauritania, Chad, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso) to tackle Islamist terrorism throughout the Sahara-Sahel region. However, Mauritania’s poverty and an unemployment rate of 40 per cent make it an inviting target for political interference and religious agitation.

Faced with what authorities believe is religious and political interference in Mauritania by Iran and Qatar and the threat posed by jihadists lurking along the border with Mali, the president has undertaken several steps to scale back Islamist activities in Mauritania, including the closing of Islamic universities and moving towards a ban on the Muslim Brotherhood. Mauritanian troops are also now operating with the French-backed Sahel Group of Five (G5S – a regional security and development alliance that includes Mauritania, Chad, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso) to tackle Islamist terrorism throughout the Sahara-Sahel region. However, Mauritania’s poverty and an unemployment rate of 40 per cent make it an inviting target for political interference and religious agitation.

The Presidential Succession

Elections last September gave the ruling Union pour la République (UPR) party a majority in Mauritania’s National Assembly. The president has promised to step down at the end of his second term in 2019, though some suspect he may still be considering a third term. Abd al-Aziz is expected to choose his own successor and may select a military man as Mauritania’s next president with the support of the solidly loyal UPR. Abd al-Aziz is a former UPR leader, but was required to officially step away from the party when he became president. The Mauritanian opposition has warned that the nation’s stability “will suffer if the next president again comes directly from the army ranks” (Arab Weekly, November 4).

General Mohamed Ould al-Ghazouni (Taqadoum.mr)

General Mohamed Ould al-Ghazouni (Taqadoum.mr)

General Mohamed Ould al-Ghazouani is considered a favorite to succeed Abd al-Aziz, but his November 4 appointment as Minister of Defense may be a sideways move intended to derail his succession. It is suggested that Abd al-Aziz fears his post-presidency influence will evaporate under a strong president like Ould al-Ghazouani, while the more pliable Colonel Cheikh Ould Baya (currently speaker of parliament and a UPR stalwart) might be more acceptable as Abd al-Aziz’s successor (Arab Weekly, November 4).

Mauritania’s Muslim Brotherhood and Islamic Education

Leading Mauritania’s political opposition is the Rassemblement national pour la réforme et le développement (RNPRD), better known as “Tewassoul.” Mohamed Mahmoud Ould al-Sidi leads the party, which is closely associated with the Muslim Brotherhood. Abd al-Aziz claims that the Muslim Brotherhood has caused the destruction of several Arab countries,” adding that the Brothers are working inside the political opposition to divide and destroy Mauritanian society (Saudi Gazette, August 31).

The Tewassoul leader has rejected charges of religious-political extremism:

“[The authorities] are extrapolating the reality of other Islamists upon us. It is better for them to give proof and facts to back their accusations. The difference between us and the others is that we are inspired by Islamic values in our political activities while others are exploiting Islam for their political benefit” (Arab Weekly, September 30).

In late September, authorities shut down two Islamic higher education institutions in Nouakchott, the Mauritanian capital. Both the University of Abdullah ibn Yasin and the Center for Training Islamic Scholars were believed to be closely tied to the Tewassoul Party. Mauritanian Muslim Brotherhood leader and prominent preacher Mohamed al-Hassan Ould Dadou was a leading faculty member at both institutions. The action resulted in student demonstrations and the arrest of two academics (University World News, October 2).

Shaykh Mohamed al-Hassan Ould Dadou

Shaykh Mohamed al-Hassan Ould Dadou

The day after the closures, Ould Dadou did not attack the government directly, but used his Friday sermon to warn that Arab countries were being “destroyed by despotism and injustice, the main causes for the destabilization of nations” swept up in the Arab Spring (AFP, September 26).

In preference to the opposition-affiliated schools, Ould Abd al-Aziz has stated his support for establishing an Islamic education center in Mauritania that would be affiliated with al-Azhar University in Cairo, a bastion of anti-extremism closely watched by the Egyptian government (MENA, March 19).

Mauritania and the Struggle for the Middle East

Mauritanians are overwhelmingly followers of the Sunni Maliki madhab (school of Islamic jurisprudence), but there are fears among top clerics and other officials in Mauritania of an Iranian campaign to convert Mauritanians to Shi’ism. [1]

Relations between Iran and Mauritania began to warm in 2008, after the military coup led by Abd al-Aziz and the consequent severing of relations with Israel. Since then, however, Mauritania has been pulled into the Arab-Iranian dispute in the Middle East and relations with Iran have suffered as a result.

Iran’s ambassador to Mauritania was called into the Mauritanian foreign ministry on May 25, where he was informed the government would not accept any activities by the Iranian embassy intended to “change the doctrine or creed of Mauritanian society.” The ambassador was further informed that the state was appointing a new imam for the Shiite Imam ‘Ali mosque in Dar Naim (a suburb of Nouakchott), where scholarships were arranged for young Mauritanians to study at Shiite institutions in Iran and Lebanon (Sahara Media [Nouakchott], May 29). For its part, Iran denied the meeting ever took place, claiming Saudi Arabia was behind the “rumors” published in Mauritanian media (Fars News [Tehran], May 30).

In early June, Mauritania was one of several Arab nations to join the anti-Qatar “Quartet” of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in cutting diplomatic ties with Qatar over its alleged support for terrorism and religious extremism. A Mauritanian government spokesman, Mohamed Ishaq al-Kenti, claimed that Qatar was funding both Tewassoul and the Mauritanian Muslim Brotherhood (Egypt Today, September 8). UPR chief Sidi Mohamed Maham stated in October that “all Qatari attempts at intervention in [Mauritania] have failed… their bad intentions are clear towards the state of Mauritania” (al-Arabiya, October 5).

The Military Dimension

Mauritania’s military struggle with modern jihadism began in June 2005, when militants belonging to Algeria’s Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (GSPC) crossed the border and attacked the Lemgheity military camp in Mauritania’s far north, killing 17 soldiers before withdrawing with prisoners, weapons and vehicles.

Only weeks after the 2008 military coup, gunmen from al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) captured a Mauritanian patrol at Tourine. All 12 members of the patrol were decapitated and mutilated (Reuters, September 20, 2008; Tahilil [Nouakchott], March 21, 2011). The incident spurred General Ould Abd al-Aziz (then President of the High Council of State) and his old comrade, General Ould al-Ghazouani, to embark on an energetic program of reforms in the military designed to increase its efficiency, skills and operational capability. The two officers first met in 1980 at the Meknes military academy in Morocco and have operated closely ever since.

The most important step in the military reforms was to create small but highly autonomous and mobile Groupements spéciaux d’Intervention (GSI) led by energetic junior officers. The GSIs, each consisting of about 200 men, are capable of finding and destroying jihadist groups from advanced positions. Arms that were once directed to presidential security units were diverted to increase the firepower of the GSIs (Jeune Afrique, November 8, 2017; Le Point Afrique, July 18). American weapons and coordination with the Mauritanian Air Force’s Brazilian-made A-29 Super Tucano light attack aircraft gave Mauritanian counter-insurgency operations a new punch.

According to General Ould al-Ghazouni, military action in not enough: “We need development, to fight against the extreme poverty of a population that has no water, no food… There cannot be a rich army and a poor population” (Jeune Afrique, November 8, 2017). The general has identified several areas where military efficiency could be improved, including the provision of updated maps, a computerized operations room and technological training for recruits (Jeune Afrique, November 8, 2017).

General Hanena Ould Sidi (NordSudJournal)

General Hanena Ould Sidi (NordSudJournal)

General Hanena Ould Sidi, who was also heavily involved in the post-2009 military restructuring, has noted it was also necessary to simultaneously strengthen the judiciary, promote development and intervene in Islamic education to discourage extremism and “to disseminate the good teaching of Islam” (Le Point Afrique, July 18).

Improvements in military performance became visible in June 2011, when the army destroyed an AQIM base in Mali’s Wagadou Forest (70 km from the border) in an attack that left 15 militants dead. [2] AQIM followed up with a retaliatory raid on the Mauritanian military base at Bassiknou, in the southeast corner of the country in July 2011, but a decisive Mauritanian air-strike the following October on the Wagadou Forest destroyed two vehicles loaded with explosives in preparation for another attack on Mauritanian positions. Local AQIM commander Tayyib Ould Sid Ali was also killed and AQIM operations against Mauritania tapered off after that.

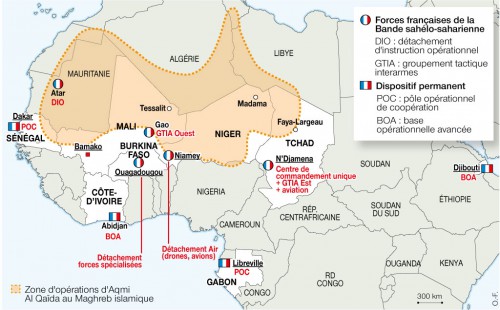

The G5 Sahel

Though Mauritania’s military is still short of funding, training and advanced arms, it is fully committed to participation in the French-backed G5S anti-terrorist alliance. The total force consists of seven battalions; two each from Niger and Mali, and one each from Mauritania, Chad and Burkina Faso. France provides intelligence and logistical assistance through its Operation Barkhane, a French counter-terrorist operation in the Sahara-Sahel region. Unlike its G5S partners, Mauritania does not allow French troops on its soil.

The GS5 has three zones of operation. The first is the Mali-Mauritania border region, the second is the triangular border region shared by Mali, Niger and Burkina Fase, while the third zone is along the Niger-Chad border. Mauritania and Mali each contribute a battalion to the G5S’s Western Zone of operations. Mauritania has a history of cross-border military operations in northern Mali, endured with varying degrees of acquiescence from the weak Malian government.

After a series of successful jihadi attacks in Mali and Burkina Faso (including a suicide bombing that destroyed the G5S headquarters), Mauritanian general Hanena Ould Sidi succeeded Mali’s General Didier Dacko as the G5S Joint Force commander in July. Ould Sidi studied at the Meknes military school in Morocco, commanded Mauritanian units in Cöte d’Ivoire and the Central African Republic (CAR) and is a former director of military intelligence in Mauritania (RFI, July 18). The new G5S second-in-command is American-educated Chadian general Oumar Bikimo, who has commanded Chadian troops in northern Chad, Mali and the CAR.

After the attack on its HQ, the G5S decided to move its headquarters from Sévaré to Bamako, but is still awaiting an exact location from the Malian government. Funds pledged to the G5S have been slow to arrive and the force is still short of vitally needed equipment (L’Indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], November 14).

Conclusion

Typical of a career military man, President Ould Abd al-Aziz is taking a direct approach to the problem of political Islam, attempting to eliminate armed Islamists beyond Mauritania’s borders while forcing domestic Islamists to the political and religious sidelines of Mauritanian society. Meanwhile, the nation’s economic weakness, high unemployment and deep Islamic traditions make it attractive to extremists. The combination of a potential state-wide ban of the Muslim Brotherhood, an aggressive military stand against jihadism and uncertainty over the presidential succession could make Mauritania a target for exploitation from regional jihadist groups such as Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin, which is highly active just across the border with Mali.

However, there are reasons why Mauritania might survive this period of uncertainty. There appears to be little internal support for armed Islamism at this time and regional jihadists do not appear to consider Mauritania a priority since their 2011 defeat in the Wagadou Forest. Much will depend on how far the president or his successor will go in attempting to root out Islamist influence in politics and education. The emergence of a significant degree of religiously-based internal dissent could act like a beacon for the region’s armed jihadists.

Notes

- United States Department of State, International Religious Freedom Report for 2017, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/281008.pdf.

- See “Mali and Mauritania Conduct Joint Operations against al-Qaeda Base,” Terrorism Monitor, July 7, 2011, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=692

This article first appeared in the December 19, 2018 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

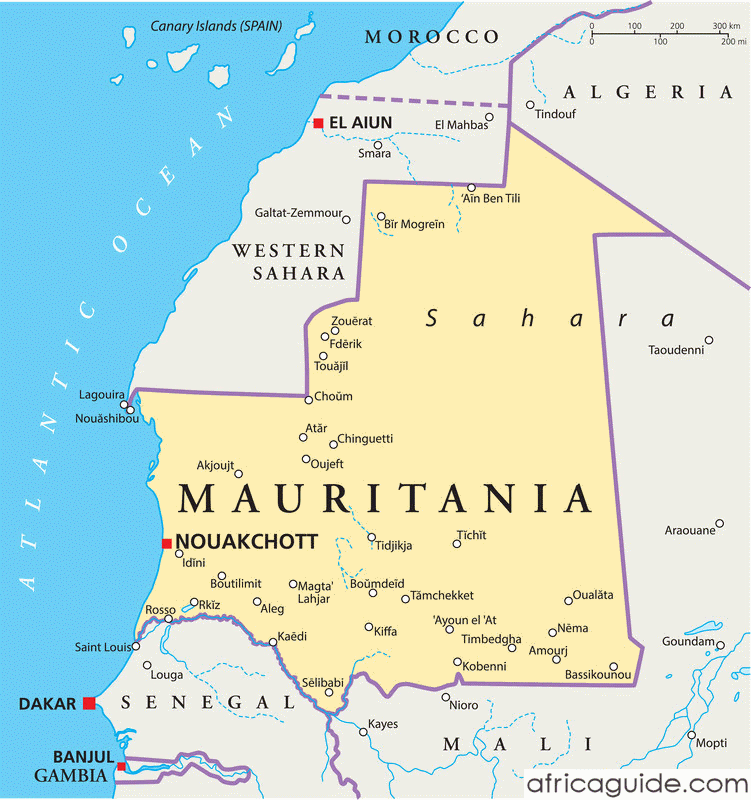

Mali-Mauritania (BBC)

Mali-Mauritania (BBC)