Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, February 21, 2021

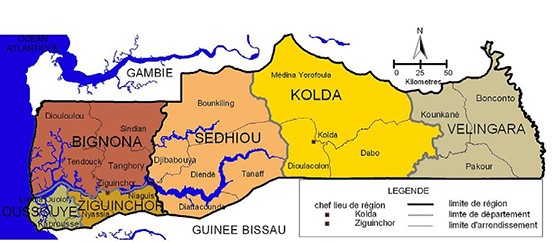

Thirty-nine years of insecurity in Senegal’s southern Casamance region may be coming to an end after a Senegalese army offensive against the most intransigent elements of a heavily factionalized armed separatist movement, the Mouvement des forces démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC – Movement of Democratic Forces in Casamance). Launched on January 26, the offensive used superior firepower to overwhelm the rebels, some of whom fled across the border to Guinea-Bissau, though they were unlikely to find a warm welcome there. For decades the MFDC took advantage of friction between Senegal and its neighbors, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau to find support and refuge when under pressure from Senegal’s army. Conditions have changed, however, with new leaders in both states friendly towards current Senegalese president Macky Sall (Pulaar [Fulani]/Serer) and less sympathetic to Casamance’s separatist movement.

The Jola (or Diola) people (4% of Senegal’s population) dominate the MFDC and its armed wing, Atika, though Jola support is far from unanimous. The Jola are also found in Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, but they are a minority among the 1.9 million people of Casamance, where they live alongside groups of Mandinka (Mandingo), Mankanya, Pulaar (Fulani), Manjak, Balanta, Papel, Baïnuk, and a small number of Wolof. The latter are the largest of Senegal’s ethnic groups, comprising roughly 43% of the population, nearly all found north of the Gambia. Resentment against the Muslim Wolof, who dominate the government, is common even among those residents of Casamance who oppose separation.

Many Jola and other Casamance groups see the prolonged existence of the MFDC as a barrier to development and the resettlement of internally displaced peoples (IDPs) in the region. Religious differences exist as well, though they do not appear to be a large irritant in relations between the Christian and animist Casamance and Senegal’s majority Muslim population (92%).

Many Jola and other Casamance groups see the prolonged existence of the MFDC as a barrier to development and the resettlement of internally displaced peoples (IDPs) in the region. Religious differences exist as well, though they do not appear to be a large irritant in relations between the Christian and animist Casamance and Senegal’s majority Muslim population (92%).

Former Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade promised to bring an end to the long-standing conflict in just 100 days in 2000; his successor, Macky Sall, promised to bring a swift end to the conflict in 2012 and repeated his pledge after re-election in 2018.

Background

A movement for regional autonomy in Casamance began under French occupation in 1947 and continued through independence in 1960. Efforts to consolidate various movements into a single body resulted in the founding of the MFDC in 1982 under the leadership of Abbé Augustin Diamacoune Senghor (Jola, 1928-2007). The armed wing of the MFDC, Atika, was formed three years later. The discovery of significant oil and gas reserves off the coast of Casamance in 1992 led to an intensification of the struggle for control over the region.

When Abbé Augustin died in Paris in 2007, the MFDC split into several factions, most of which now favor the negotiation of a final peace accord (Senego.com [Dakar], February 24, 2020). Even the movement’s hard-line factions have observed a unilateral ceasefire since 2014, though incidents of violence have occurred and the forests of Casamance remain a dangerous place.

The Changing Roles of Gambia and Guinea-Bissau in the Casamance

The MFDC used to receive substantial assistance from Gambian president Yahya Jammeh, a Jola Muslim who took power in a 1994 coup d’état and maintained it through the deployment of death squads and the systematic use of torture. Jammeh’s depraved rule ended when he lost the 2016 presidential elections to Adama Barrow, and was followed by his flight to Equatorial Guinea in January 2017. Adama Barrow, by contrast, is considered to be politically close to Macky Sall.

Revelations about Jammeh’s rule presented to Gambia’s ongoing Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) have shocked Gambians. Gambia’s strange situation as an Anglophone nation bordered on all sides (save the coast) by Francophone Senegal dates back to its former status as a British colony. Casamance was itself a Portuguese territory until 1888, when it was transferred by treaty to the French colonial administration of Senegal.

For Dakar, another promising development arrived last year when Umaro Sissoco Embaló became president of Guinea-Bissau in a disputed election. Embaló’s predecessors were generally supportive of the MFDC but the “election” of Embaló, another ally of Macky Sall, has allowed a new spirit of cooperation with Dakar.

Last November, a delegation from the Bissau-Guinean armed forces visited Ziguinchor to hammer out terms for a series of bilateral agreements designed to address security issues in the border region, including drug trafficking, illegal resource extraction, organized crime and cattle theft (SenePlus [Dakar], February 5, 2021). These meetings helped set the stage for the current offensive.

On February 4, the Maquis Casamançais warned Guinea-Bissau that if it allowed Senegalese troops to use its territory to attack the MFDC, the movement’s fighters would “grant themselves all the rights of pursuit of the Senegalese soldiers, wherever they are, into the interior of Guinea-Bissau” (Journal du Pays, February 4, 2021).

The shelling of areas close to the border with Guinea-Bissau carries some risk for bilateral relations; MFDC militants reported the shelling of the Bissau-Guinean village of Mankamounkou on January 27 by Senegalese artillery, leading them to speculate on the possibility of war between the two nations (Journal du Pays, January 29, 2021). Though this would be favorable to the militants (but ultimately devastating to Casamance), there seems little chance errant shelling will provoke such a conflict.

When President Embaló returned from a visit to Dakar on February 13, he announced the discovery of a plot to assassinate him, his Minister of the Interior and the Minister of Defense. No further details or evidence were presented or made available from the ministries involved, suggesting the announcement was part of an effort to eliminate rivals to his still-contested presidency and consolidate power (E-global notícias em Português, February 17, 2021; Journal du Pays, February 16, 2021).

The New Offensive

With no signs of a settlement in sight despite years of negotiation, Senegal’s military launched a new offensive in the Casamance on January 26 in its latest attempt to secure the region and return displaced communities. The offensive followed only days after 80-year-old MFDC leader Edmond Borra demanded new negotiations on the anniversary of the death of Abbé Diamacoune on January 20, though he acknowledged the difficulty of arranging talks while the MFDC remained divided. (Sud Quotidien [Dakar], January 21, 2021). Borra appeared to oppose the continuance of armed resistance when the offensive began, saying: “We can’t continue to shoot each other without negotiating for 40 years” (AFP, February 11, 2021).

A statement from a Senegalese army spokesman described the operation’s objectives:

- Neutralize armed elements abusing the local population

- Combat the trafficking of cannabis and timber

- Provide security support to local populations (RFI, January 30, 2021).

Over the past year, Dakar has also focussed on the resettlement of Casamance’s IDPs. Some communities have been unable to return to their homes for as long as 28 years due to the presence of landmines and gunmen who often accuse farmers of being informants for the army (SenePlus [Dakar], February 5, 2021; IRIN, August 26, 2009).

To carry out the offensive, the Senegalese Army deployed 2600 soldiers, 11 French-built Panhard AML-60-20 Serval armored reconnaissance vehicles, eight self-propelled guns, 14 Toyota 4x4s, two reconnaissance planes and two helicopters (Journal du Pays, February 10, 2021). Most of the army’s operations took place in one area of roughly 150 km² between the Bissine Forest south of the Casamance capital of Ziguinchor to the border with Guinea-Bissau.

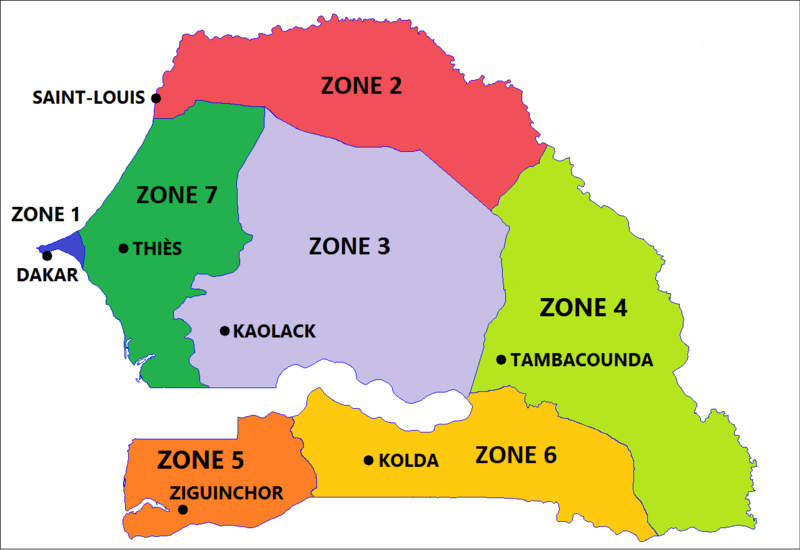

The assaults were led by Lieutenant Colonel Mathieu Diogoye Sène commanding the 3rd Infantry Battalion based at Kaolack, and Lieutenant Colonel Clément Hubert Boucaly, leading the commando battalion from Thiès. Three Atika bases roughly 12 miles from Ziguinchor were overrun on February 3 after intense shelling and aerial bombardment, with the militants fleeing into the bush with their weapons and other goods (RFI, February 3, 2021). A further base was taken on February 4.

The first base to be taken was Bouman, where the commando battalion encountered “somewhat intense” resistance before the defenders fled at the sight of a reconnaissance plane (Seneplus [Dakar], February 17, 2021). The 3rd Battalion took Boussouloum and Badiong; rebel sources claimed the death of eleven Senegalese troops in the taking of Badiong, but the army admitted only to the much more likely figure of one soldier wounded (Agence de Presse Sénégalaise, February 11, 2021). The commandos then turned their attention to Sikoun, which also fell quickly (Seneplus [Dakar], February 17, 2021).

According to Colonel Souleymane Kandé, commander of Senegal’s military zone no. 5 (Ziguinchor), the operations against the MFDC bases were carried out with assistance from Guinea-Bissau’s defense and security forces (Guardian [Lagos], February 10, 2021). The Bissau-Guinean army moved forces up to the border to prevent the conflict from spilling over, though their resources are small and the border easily infiltrated. Armed MFDC elements accused Guinea-Bissau’s President Embaló of allowing Sengalese military units to use a corridor through his country to attack the MFDC from the rear, as well as allowing small Bissau-Guinean units to join in the assault, an action legitimized by the recent defense agreements with Macky Sall’s government (Journal du Pays, February 5, 2021).

According to Colonel Souleymane Kandé, commander of Senegal’s military zone no. 5 (Ziguinchor), the operations against the MFDC bases were carried out with assistance from Guinea-Bissau’s defense and security forces (Guardian [Lagos], February 10, 2021). The Bissau-Guinean army moved forces up to the border to prevent the conflict from spilling over, though their resources are small and the border easily infiltrated. Armed MFDC elements accused Guinea-Bissau’s President Embaló of allowing Sengalese military units to use a corridor through his country to attack the MFDC from the rear, as well as allowing small Bissau-Guinean units to join in the assault, an action legitimized by the recent defense agreements with Macky Sall’s government (Journal du Pays, February 5, 2021).

The captured bases were barely worthy of the name, consisting of tin and wood shelters and a few very small underground bunkers (Guardian [Lagos], February 10, 2021). Among the weapons seized by the army were Soviet-made B-10 recoilless rifles, French-made FAMAS bullpup assault rifles and American-made M203 grenade launchers (Seneplus [Dakar], February 17, 2021). More common, however, were well-used bicycles, old mattresses and decrepit firearms of no value. Fields of cannabis were found attached to the bases. These are believed to have provided revenue for arms purchases and other MDTC expenses.

In the midst of the offensive, opposition politicians called for President Macky Sall to declare the MFDC a terrorist organization and cease all dialogue with the movement (Senego.com, February 5, 2021).

Factions:

Though veteran separatist Salif Sadio claims the leadership of the MFDC’s armed wing, his following has diminished greatly and there are several factions that do not recognize him. It is these that have been the main target of the army’s offensive. A spokesman for Salif Sadio insisted that the MFDC leader was not involved in the current fighting with government forces (VOA Portugues.com, February 5, 2021).

César Aoute Badiate (Le Quotidien)

César Aoute Badiate (Le Quotidien)

The other factions include:

- The Kassolol faction, led by César Atoute Badiate. Part of the so-called “southern front,” the faction operates near Senegal’s south-west border with Guinea-Bissau and does not appear to have been involved in the recent fighting. Badiate, a nephew of Father Diamacoune, does not support Salif Sadio. The two have been rivals for 20 years, with clashes occurring between their factions in 2006. César survived the 1998 purge and execution of some 30 of Salif Sadio’s rivals within the movement, though he suffered an eye injury when Sadio’s assassins attacked him at his refuge in Guinea-Bissau (Le Témoin [Ziguinchor], February 17, 2021; Dakaractu, February 5, 2021).

- The Sikoun faction, based in the Goudomp department of the central part of Sédhiou region. Led by Adama Sané, this faction strongly opposes the return of IDPs. Sikoun was once the base of the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC – African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) during Guinea-Bissau’s struggle for independence from Portugal in the 1960s. Government artillery fire was directed at the staff headquarters of Commander Adama Sané and his Sikoun faction on February 2 and 3, with the base falling on February 4 (RFI, February 5, 2021).

- The faction of Ibrahim Kompasse Diatta, leader of the Sikoun faction until April 2020, when he came under suspicion from other elements of the movement for contacts with Casamance politician and Macky Sall. His group ran bases 2 and 9, both of which fell on February 3.

- The Diakaye faction (northern front), commanded by Fatoma Coly. This group supports the Sikoun faction but does not appear to have been targeted in the recent offensive (Le Témoin [Ziguinchor], February 17, 2021).

The Propaganda War

Senegal’s government provided little information about the offensive once it was underway, allowing the MFDC to claim various small triumphs without official refutation. Indeed, only days before the offensive began, a senior government official, Aubin Jules Marcel Sagna, insisted in October 2020 that declared “the war is over in Casamance,” adding three months later that “there is less insecurity in Casamance than elsewhere because of the determination of the Casamance people to find peace” (Voice of Gambia, October 13, 2020; DakarActu, January 14, 2021).

Conversely, MFDC sources reported the death of three Senegalese soldiers in an ambush on January 30, with the bodies of two more soldiers discovered in the bush the next day by sniffer dogs (Journal du Pays, February 1, 2021; Journal du Pays, February 2, 2021). On February 3, the MFDC announced the death of four Senegalese soldiers after their vehicle hit an anti-tank mine (Journal du Pays, February 3, 2021). Another MFDC report claimed the deaths of 12 Senegalese soldiers at the entrance to the Bissine Forest and the destruction of three AML-60-20 Serval armored reconnaissance vehicles on January 29 (Journal du Pays, February 2, 2021; Journal du Pays, February 2, 2021). Finally, Casamance media reported the defection of 21 Senegalese soldiers of Casamance origin with their arms and important intelligence to the Atika wing of the MFDC on February 16 (Journal du Pays, February 16, 2021). Most of these claims appear to be of dubious value, especially considering the ease with which Senegal’s military overran MFDC bases.

Timber: A Motivation for Conflict

Stocks of highly valuable rosewood, teak and other hardwoods in the forests of Casamance have helped fuel the conflict. As these woods have grown scarce worldwide, prices as well as demand have soared, especially in China, where rosewood is valued for shipbuilding and use in traditional hongmu furniture, China having depleted its own stocks of the high-value wood.

Economic hardship caused by the unresolved conflict fuels the search for lucrative hardwoods by a struggling population. The deforestation has diminished crop yields and forced local farmers to trade yet more timber for rice, creating a loop of environmental devastation. Locally-stationed Senegalese troops may also be facilitating the trade; the smuggling of trailer-loads of hardwood logs to Gambia over the region’s few roads is nearly impossible to conceal from any type of vigilant authority (Mongabay.com, November 5, 2020). Despite having logged its own rosewood stocks to extinction several years ago, Gambia continues to be a main supplier of the wood to China, nearly all of it obtained illegally from Casamance (Mongabay.com, November 5, 2020). [1] Chinese agents move the illegally cut timber through the Gambian port of Banjul. Despite formal agreements between Gambia and Senegal to end the trade, rosewood exports through the Gambian port of Banjul have actually increased in recent years, with the exception of a brief pandemic-related decline last year.

Though the MFDC has been implicated in the illegal export of valuable hardwoods from Casamance, Atika units have presented themselves as protectors of the forest, reporting the seizure of loads of timber from government water and forestry agents as well as timber traffickers who underwent “tough interrogation” to discover the names of the organizers of the illegal trade (Journal du Pays, January 26, 2021). In the past, the movement has admitted to beating loggers and burning their vehicles as well as accusing the army of involvement (Jeune Afrique/AFP, January 24, 2020). It is likely that there is no common approach to the trade amongst the various MFDC factions, all of whom are in need of funding to prolong their existence. The MFDC is estimated to have earned $19.5 million from the illicit trade between 2010 and 2014 (OCCRP, March 27, 2019).

As a popular inducement to participate in the logging of local hardwoods, Chinese and Indian multinationals have offered motorcycles to young men willing to work in the forest. The motorcycles, in turn, are used for smuggling and drug trafficking between Gambia, Casamance and Guinea-Bissau (Sud Online [Dakar], January 25, 2021).

Turkish Military Involvement?

Turkey has been active in recent years in developing economic and diplomatic ties with both Senegal and Gambia (Daily Sabah, January 30, 2021).

MFDC sources claimed that Turkish troops were on the frontline of the assaults on their bases since January 31. On February 5, Atika reported that it was in a “strategic retreat” after ten days of attacks by Senegalese and Turkish troops (Journal du Pays, February 5, 2021). The movement points to the February 2 visit of Macky Sall and Umaro Sissoco Embaló to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Istanbul as proof of Turkey’s interest in regional offshore oil projects. The militants further claim to have learned from Turkish sources that new contracts were signed for the provision of arms and Syrian jihadists employed as mercenaries, similar to the pattern of Turkey’s intervention in support of the Government of National Accord (GNA) in Libya. According to these sources, the arms and fighters are due to arrive in Senegal in the last week of February (Journal du Pays, February 2, 2021).

Turkey’s economic and political overtures to Senegal have been countered by offers of assistance from Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, a rivalry that has already played out as backers of rival sides in the Libyan conflict. US Senator Lindsey Graham has encouraged greater Turkish involvement in Africa as an alternative to China’s growing influence: “Nothing would please me more than to partner with Turkey to offer to the African continent alternatives to Chinese products and Chinese influence” (Anadolu Agency [Ankara], June 25, 2020).

Senegalese troops have been active in the Middle East for some time, having been deployed in Saudi Arabia since 2015 as part of the campaign against the Shi’a Houthis in Yemen. [2] Senegalese troops arrived on Yemen’s Socotra Island in October 2020 to support the construction of a United Arab Emirates military base in the strategically-located archipelago.

The occupation of their bases, the resettlement of unsympathetic IDPs and the denial of cross-border refuges or other assistance are squeezing out the last hard-line Casamance separatists. Reduced to being friendless fugitives in the forests of Casamance, it seems unlikely the armed resistance can make any kind of come-back. Dakar’s decision to take advantage of new political realities in the region and make a demonstration of force will compel the remaining and generally more moderate factions to enter immediate and sincere negotiations or possibly meet a similar fate. After 39 years, Dakar has identified endless negotiations as the facilitator of prolonged insecurity in what should be a prosperous part of the nation. The MFDC cannot bargain from a position of strength; its military weakness has been exposed and the movement has clearly lost any broad support it might have once enjoyed. In some non-Jola quarters, tired of insecurity, economic struggle and the decades-long dislocation of various Casamance communities, the movement has earned a reputation as nothing more than a tribal-based bandit group.

Notes:

- Just 3% of Gambia is still forested; the remaining stocks are of low quality (OCCRP, March 27, 2019).

- See “Senegal’s Military Expedition to Yemen: Muslim Solidarity or Rent-an-Army”? AIS Tips and Trends: The African Security Report, July 30, 2015, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3358.