Civil War Roundtable

Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto

November 21, 2018

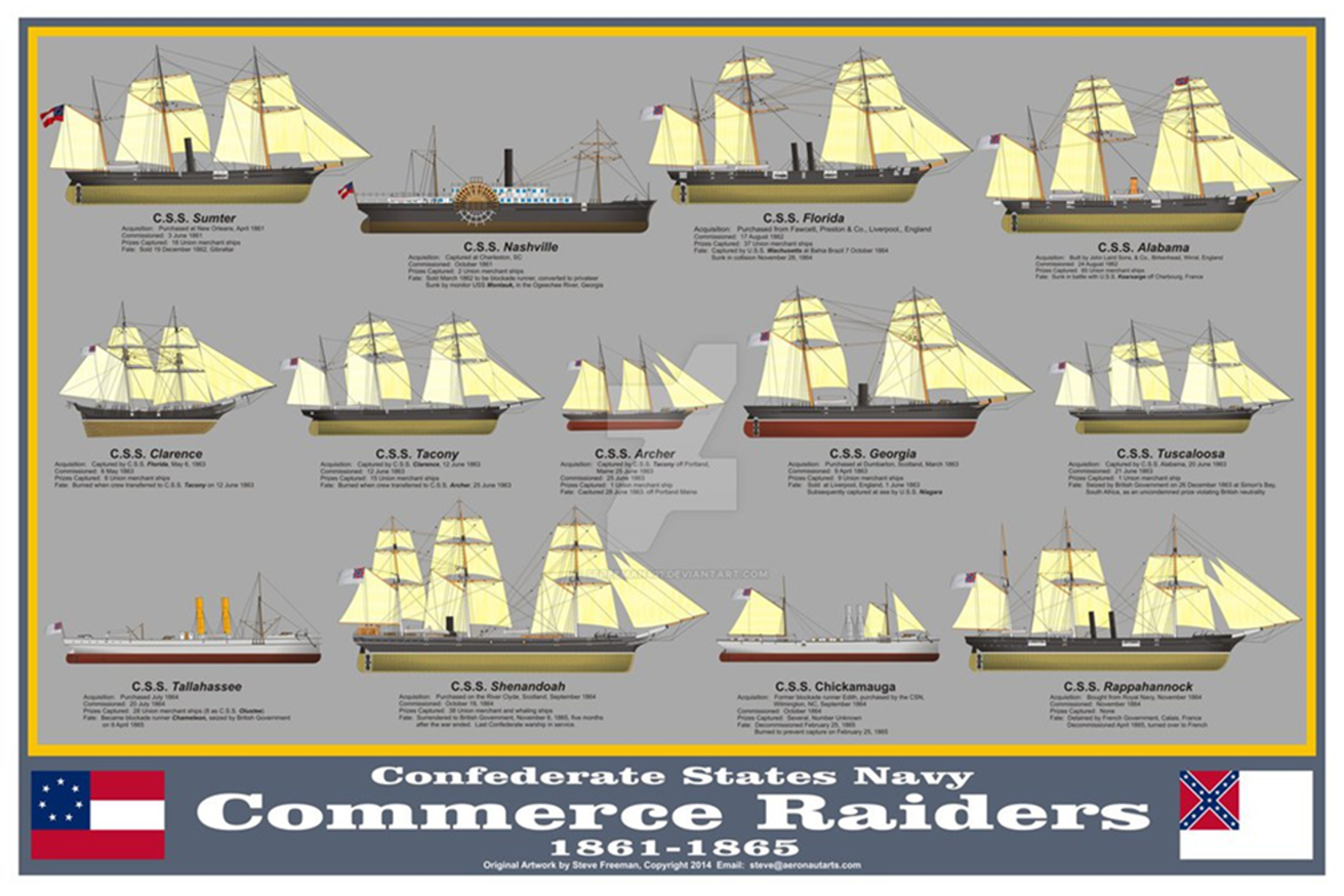

Far from the grinding slaughter of the American Civil War was another front, one where, for the most part, casualties consisted of property rather than young lives. This was the campaign undertaken by a small number of Confederate commerce-raiding ships to drive the Union’s vast merchant fleet from the Seven Seas and to draw away Union warships imposing a crippling blockade on Southern ports.

The campaign was one of both monotony and wild adventure, often fought in remote and exotic locations in both baking heat and bone-chilling cold. The most famous of these cruisers were the Alabama, the Florida and the Shenandoah, making cruises as long as two years with the illumination of burning Union ships to mark their progress.

As the war went on and it became apparent that the South had little chance of winning, commerce raiding actually intensified. The captains and officers of these ships went to sea in the knowledge that popular opinion in the North demanded they be hung as pirates.

The Privateer Model

Granting letters of marque to privateers was the usual model for states at war that wished to destroy enemy commerce at no risk or liability to themselves. Privateers worked not out of loyalty, but for the prizes they were entitled to take by their dubious authority. This was tried in the early Confederacy, but when it became clear that privateers could not easily bring their prizes back through the blockade into the southern states, privateering came to an abrupt end. There was, however, money to be made from blockade-running, and this is where financial backers went.

In Richmond, it became clear that new measures were called for. Ships flying the flag of the Confederacy, manned by commissioned Southern officers and part of an official navy would sail the seas to intercept shipments of Federal war supplies and destroy Union shipping in general.

Britain decided early in the war to bar privateers from its ports, providing another incentive for the Confederacy to bring its commerce raiders under naval command, which would allow the ships to access British ports as a belligerent power, with the various restrictions covered by international law.

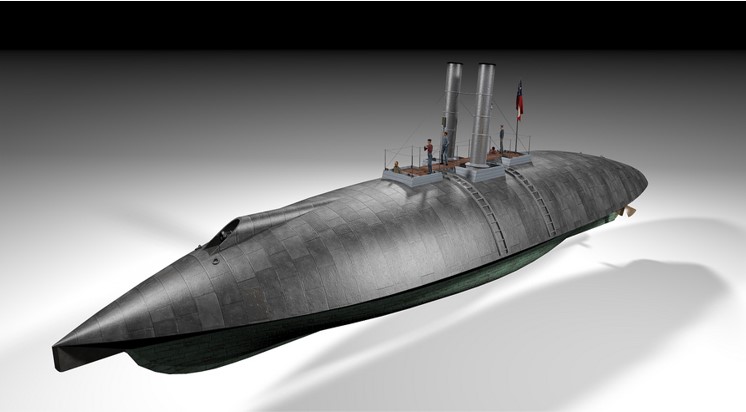

The CSS Manassas, the Confederacy’s first ironclad, began its career as a privateer. Using the engines and hull of a steam tug-boat, private investors in Louisiana commissioned an innovative design, combining a powerful ram with a 32-pounder gun in its bow. The ship was expropriated by the Confederate Navy and its original crew of thugs driven off by a single naval officer.

The Manassas participated in two major battles on the Mississippi, ramming both the USS Brooklyn and the USS Mississippi. When the ironclad attempted to prevent Admiral Farragut from running the Union fleet past Forts Jackson and St. Philip, it ran aground and was set on fire by the guns of the USS Mississippi. Eventually the Manassas drifted downstream while still on fire until its magazine exploded.

Lincoln’s proclamation of the blockade included a warning that anyone caught molesting Union shipping would be treated as a pirate and hanged. When it appeared that some captured privateers would be executed, Jefferson Davis ordered an equal number of senior Union officers held prisoner to be executed if Lincoln’s orders were carried out. They were not.

By 1863, the privateers had pretty much disappeared, replaced by the Confederate Navy’s commerce raiders.

Captain James Dunwoody Bulloch

James Dunwoody Bulloch (left) with his brother, Irvine Bulloch of the CSS Alabama

James Dunwoody Bulloch (left) with his brother, Irvine Bulloch of the CSS Alabama

The main Confederate naval agent in Britain was Captain James Dunwoody Bulloch, an extremely resourceful character who produced a mixture of triumphs and disappointments in his efforts to supply the Confederacy with modern naval ships. Most of the disappointments were due to the tireless efforts of American diplomatic officials and their agents to ferret out well disguised plans to purchase or build warships in Britain and staff them with British crews. Obtaining ships, weapons and crews for use in a conflict to which Britain was not a party was a violation of that nation’s Foreign Enlistment Act, so subterfuge was called for.

Bulloch believed that winning the naval war in home waters was more important than launching commerce raiders, saying “The destruction of unarmed and peaceful merchant vessels… is not defensible upon the principles of moral law.” Nonetheless, he continued to follow orders to assemble a European-built fleet capable of smashing the Union blockade.

In the shipyards, the more obviously warlike the ships under construction were, the more attention they drew from the formidable intelligence network presided over by the US Ambassador to Britain, Charles Francis Adams. Bulloch ran his own network of secret agents who warned Bulloch of impending seizures of ships being built for the Confederacy.

The ships built in Britain and France were paid for in cotton, the only real currency the South possessed in any quantity.

Bulloch also handled the financing of blockade-runners. Several Confederate commerce raiders became blockade-runners under new names; others had been blockade-runners before being purchased and armed by the Confederate government. Bulloch also handled financing for Confederate intelligence operations in the British Empire, including Canada. There were accusations after the war that he may have funded the conspiracy to kill Abraham Lincoln.

The Commerce Raiders

A common process was followed with most of the European-built ships. Still unarmed, they slipped out to sea to rendezvous at some remote place with tenders carrying all the guns and military gear. At this point the officers donned their Confederate naval uniforms and informed the crew of the true nature of their voyage. The sailors were given the option of staying with the ship or returning with the tender. Many sailors were veterans of Her Majesty’s Navy, and the fact that some of these were still members of the Royal Naval Reserve created yet more violations of the Foreign Enlistment Act.

Desertions, expired contracts and illness ate away at crew numbers, and the cruisers were forced to recruit from the crews of their prizes. When the CSS Florida reached Martinique after two years at sea, its crew was mostly Italian, Austrian and Greek, with smaller numbers of French, English and Americans. Nearly all had been recruited from the crews of captured vessels. When the CSS Alabama went down, there were 19 different nationalities on board. Portuguese, Spaniards, Malays, Prussians, Frenchmen and even South Seas islanders all served on the commerce raiders.

Desertions, expired contracts and illness ate away at crew numbers, and the cruisers were forced to recruit from the crews of their prizes. When the CSS Florida reached Martinique after two years at sea, its crew was mostly Italian, Austrian and Greek, with smaller numbers of French, English and Americans. Nearly all had been recruited from the crews of captured vessels. When the CSS Alabama went down, there were 19 different nationalities on board. Portuguese, Spaniards, Malays, Prussians, Frenchmen and even South Seas islanders all served on the commerce raiders.

Prisoners were another problem, with the cruisers forced to host large numbers of men from their prizes until they could be offloaded to some agreeable neutral ship or dropped at some port to find their own way home.

The commerce raiders were under strict orders not to directly engage Union warships unless there was no other alternative. The best possible result of such a fight was the destruction of a single Union warship, but remaining at large on the seas meant multiple warships would be drawn away from the blockade to pursue the raider. This, and the destruction of Northern merchantmen and their cargoes, was the real mission of the cruisers.

Stealth was central to commerce raiding – the cruisers carried a chest of international flags for use in luring trusting victims to their doom. Some ships tried to make a run for it after receiving a shot across the bow, leading to dramatic sea chases which the best Confederate cruisers usually won with their combination of steam and sail.

Most of the commerce raiders had little expectation of docking in any Confederate port, so provisions were obtained from their victims and repairs made in foreign harbors. These repairs were allowed to belligerent powers under international law so long as the military power of the ship was not enhanced or its complement of sailors increased. If a Union ship was present in the same foreign port, it was not allowed to take any action against the Confederate vessel, nor could it follow the ship when it left the port for 48 hours or to engage it within the three-mile range of national waters. Once discovered by a Union ship, it became imperative for a cruiser to leave a foreign harbor as quickly as possible before other Union ships could close in and trap it.

The Union never adopted convoys as a means of protecting their merchant fleet. The North never had enough ships to maintain both convoys and the blockade, so the latter was judged more important and the merchantmen were left to their fates. Convoys only work when there is a common destination; they cannot protect ships going to a variety of ports.

Discipline was always a problem on the cruisers, given that, other than the officers, the crews were not from the southern states and had no loyalty to the Confederate cause. Raphael Semmes, the commander of the Alabama, noted that many of the crew had the belief they were on some sort of privateer where “they would have a jolly good time and plenty of license.” He convinced these men otherwise with what he termed “a strong hand.” Confederate Marines served on all the cruisers to enforce the officers’ orders, but little is known about them as all their records were destroyed in a fire shortly after the war.

Drunkenness was a constant problem, especially when the crew discovered stores of alcohol in one of their prizes. When the Shenandoah seized a ship carrying 50 barrels of liquor and over 2100 bottles of spirits, a four-day drunken riot ensued before the officers could restore order. Fighting, insolence, theft and neglect of duty were other common offenses. Discipline could be enforced by extra duties, cancellation of grog, heavy fines, being clapped in irons, gagging or tricing. The latter was an unofficial naval punishment that gained popularity after flogging was banned and involved being hung by the wrists for hours with the feet barely touching the deck.

Ships’ officers tended to be very young. On the Shenandoah, 25-year-old Executive Officer William Whittle was expected to deal out discipline to older, hardened men with no real loyalty to the South or its cause. His commander, “Old Man Waddell,” was 41.

The captain of the Alabama came to trust his young officers; Captain James Waddell, however, never did, and often rose from his bed in the middle of the night to countermand the sailing orders of his subordinates. This drove a wedge between the captain and his young officers.

A small number of slaves were also part of the cruisers’ crews, usually employed in the galley or as stewards. The Alabama had two slaves in its complement; both died in its final battle. The Shenandoah had two free Blacks in its crew; one had eagerly volunteered after his ship was taken; the other was a veteran of the US Navy who had been aboard the USS Minnesota when it was attacked by the Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads. Impressed as a cook, he was a constant discipline problem, being triced as many as three times a week before he deserted.

Since Britain, France, Spain and their colonies all prohibited prizes from being brought into port for sale, there was little alternative for the cruisers to do anything more than burn, scuttle or bond their prizes. The latter practice spared the ship, but was actually a form of ransom in which the ships’ owners were obliged to pay a heavy fine to the Confederate government at the conclusion of the war. The practice presumed a Confederate victory or negotiated settlement would conclude the war.

The crews of the commerce-raiders were promised prize money for every ship ransomed, burned or sunk. The value of the vessels and their cargoes were carefully recorded in the ship’s log and the funds were to be paid out by the Confederate government at the end of the war. Needless to say, none of these funds appeared after the collapse of the Confederacy. Many sailors discovered there was far more money in blockade-running, which offered high wages and space within the ship to store their own speculative cargoes.

In general, the commanders of the commerce raiders did not allow looting of the ships they captured in order to avoid charges of piracy, but these rules were interpreted in different ways. One veteran of the Alabama complained: “Whenever we took a prize, the officers always made a rush for all the good eatables and drinkables, while the men were not allowed a single article, and severely punished if they touched anything.” Captain Semmes believed that relaxation of this rule could encourage boarding parties to try and take possession of the entire prize for themselves.

The most important parts of a cruiser intended to remain at sea for a long time were steam condensers to produce fresh water from salt water, and large coal bunkers that enabled the steamers to avoid entering foreign ports where they could be trapped by Union ships. Being composite vessels, they usually remained under sail, bringing their iron propellers into play only when necessary.

The crews became experts in arson, learning all the best techniques to send a ship up in flames. The sight of wooden ships blazing through the night in the midst of a vast ocean left indelible impressions on those involved. Many approached the work with enthusiasm; an officer recalled of one ship: “As she had no oil aboard, we found it a little hard to get the fire going, but when it did start, it burned beautifully.” Semmes described the sound of a burning ship as “the sound of a thousand furnaces.”

CSS Nashville

One of the earliest Confederate commerce raiders was the CSS Nashville, converted from a passenger-carrying paddle wheeler with powerful engines. The Nashville took only two prizes, but was politically important for being the first Confederate ship to arrive in a British or European port. US Ambassador Charles Adams demanded the British treat it as a pirate vessel, but Foreign Secretary Lord Russell declared it was a belligerent vessel with a regular crew, thus granting it the usual protections under international law.

CSS Nashville burns the Harvey Birch

CSS Nashville burns the Harvey Birch

With the legal status of the Confederate ships settled in Britain, the rest of Europe followed suit in what was a vital development for the survival of the small Confederate navy. Evading the USS Tuscarora, the Nashville returned to North Carolina loaded with Enfield rifles and eight batteries of artillery in February 1862.

The Nashville briefly entered service as a blockade-runner as the SS Thomas L. Wragg and then as a rare privateer under the name Rattlesnake. Before it could take any prizes, the Rattlesnake was destroyed by the monitor USS Montauk in the Ogeechee River of Georgia.

Raphael Semmes and the CSS Alabama

Captain Raphael Semmes was the most famous of the cruiser commanders. He began his raiding in the CSS Sumter, a former passenger steamer that was not especially suitable for use as a commerce-raider, but Semmes thought she had “a saucy air about her,” and undertook extensive renovations to turn her into a warship.

CSS Sumter Burns the Neapolitan off Gibraltar

CSS Sumter Burns the Neapolitan off Gibraltar

After running the blockade, Semmes and his crew learned their new trade well, taking 18 prizes and burning seven. Its last two victims were taken off the coast of Gibraltar in April 1862. Afterwards the Sumter was trapped in Gibraltar’s port by Union warships and had to be abandoned.

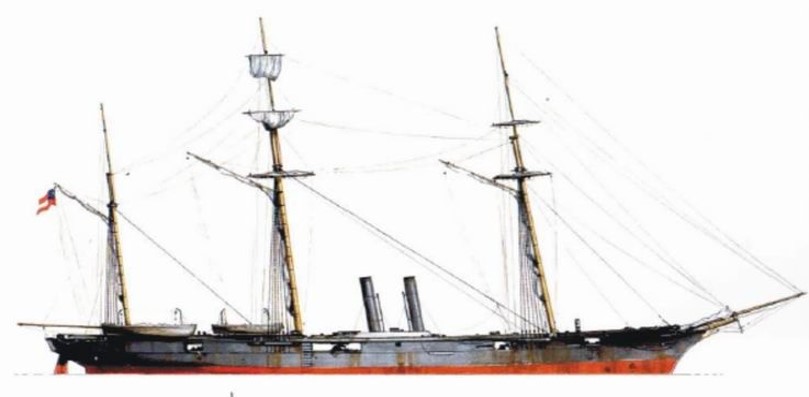

Semmes’ next command was the Alabama, a British-built composite steamer armed with six 32-pounder guns on its flanks and two pivot guns, an 8-inch smoothbore and a 100 pounder Blakely rifle.

CSS Alabama vs the USS Hatteras (foreground)

CSS Alabama vs the USS Hatteras (foreground)

In January 1863, the Alabama took on the USS Hatteras off Galveston. The guns of the Union’s paddle-wheel cruiser were no match for the Alabama’s, and the Union ship was sunk in only 13 minutes. This battle left other Union ships wary of tackling Confederate cruisers without support.

As the Alabama’s cruise went on and accusations of piracy became louder, Semmes seemed to take on a more piratical appearance, terrifying the masters of captured ships as he examined their papers in his cabin, stroking his ever-longer waxed mustache in front of a collection of chronometers taken from ships that had failed the test and been sent to the bottom.

Captain Semmes and First Mate John McIntosh Kell, CSS Alabama

Captain Semmes and First Mate John McIntosh Kell, CSS Alabama

After two years at sea, the Alabama was bottled in at the French port of Cherbourg in June 1864 by the USS Kearsage. Semmes’ choices were to offer battle to the Union ship before even more federal ships arrived, or to abandon the Alabama in port. The prestige of the Confederacy had been blemished by the defeat at Gettysburg and Semme’s own reputation tarnished by charges of piracy. In this situation, Semmes sought and received permission to engage the Kearsage. Semmes sent the captain of the Kearsage a brief note, reading: “I am undergoing a few repairs here which I hope will not take longer than the morrow. Then I will come out and fight you a fair and square fight.”

As the ships circled in the Channel, hurling shot and shell at one another, Semmes realized two things;

(1) The fire of the Alabama was having little effect on the Kearsage, due to the latter’s use of heavy chains draped over the sides of the ship, and (2) the superior speed of the Kearsage would make an Alabama victory difficult. Semmes attempted to resolve these issues by getting in close enough to board the Union whip, believing his veteran crew would make quick work of the less-experienced crew of the Kearsage. The attempt failed, and only resulted in greater damage to the Alabama from close-range fire.

Another reason for the Alabama’s inability to destroy the Kearsage was the powder in the Alabama’s shells had deteriorated at sea. The Alabama nearly ended the battle when it struck the stern of the Kearsage near its screw with a 100-pound percussion shell, which lodged in the ship’s timbers but failed to explode. The entire section was later removed and displayed as a relic of the battle.

With the Alabama steadily taking on water that threatened to put out her fires and most of her guns out of commission, Semmes struck his colors and ordered the survivors to abandon ship.

The Sinking Alabama Lowers its Flag

The Sinking Alabama Lowers its Flag

Even the sinking of the Alabama incited controversy; Semmes and a number of his officers escaped capture and probable trials for piracy when they were plucked from the water by the Deerhound, a private English yacht that took them to safety in England rather than turn them over to the victorious Americans, who claimed they had a right to take the Alabama’s crew as prisoners since the ship had surrendered to the Kearsage.

The wreck of the Alabama was discovered in 1984 by a French navy mine-sweeper. Two five-ton guns were raised in 2000, along with the ship’s bell, items of furniture, tableware and even a human jaw found under a gun.

By the time it sank, the Alabama had captured 65 Union merchantmen and burned 52 of them, with a total value of over $4.5 million. In 22 months, it had boarded 447 ships and taken over 2,000 prisoners.

After safely returning to the South via Cuba, Semmes was placed in command of the freshwater James River Squadron, using the ironclad Virginia II as his flagship.

The CSS Florida

The CSS Florida left the Liverpool shipyard where it was built in March 1862. When it arrived in Nassau it was temporarily interned and its crew of 130 dispersed. When the ship was returned to its Confederate commander, John Maffitt, he was able to recruit only 20 local men to take it back to sea to load the guns and other war materiel that had arrived separately from Scotland. Things got worse, as Yellow Fever struck Maffitt and the small crew, killing four, including Maffitt’s stepson.

Incredibly, Maffitt was able to run the Florida through the Union blockade into Mobile, Alabama, where he was able to enlist a new crew. The ship was blasted by Union warships as it made its run into Mobile, and repairs took four months. Maffitt then made a brilliant night-time escape past nine Union warships determined to catch her leaving port.

The Florida was a great success as a commerce raider. One of its victims carried 10,000 boxes of fireworks from China, creating a spectacular display as it burned through the night. After taking many prizes, Maffit’s health failed and he left the ship at Brest in August 1863.

His successor, Lieutenant Charles M. Morris, continued to have triumphs until he sailed into the harbor of Bahia in Brazil, where the USS Wachusett was also docked. Morris accepted Brazilian guarantees of his safety in the harbor under international law and decided to allow his men much-needed shore leave. After 12 hours the starboard watch returned roaring drunk and the port watch was allowed ashore. At 3 in the morning the Wachusett illegally attacked and seized the ship, towing it away before the Florida’s port watch could return.

The Brazilians were outraged and demanded the return of the Florida, but the cruiser was taken to Hampton Roads, where it sank in mysterious circumstances. The Wachusett’s captain, Napoleon Collins, was court-martialled for his violation of international law, but later pardoned by US Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles.

The CSS Rappahannock

The CSS Rappahannock in Calais

The CSS Rappahannock in Calais

An example of how desperate the Confederacy could be at times to acquire ships for commerce raiding is the sad story of the CSS Rappahannock, also known as “the White Elephant.” Originally the HMS Victor, the 500-ton dispatch steamer was judged defective by the Admiralty and sold at auction in November 1863. Its sale to a Confederate agent pretending to be interested in using her in the China trade was quickly detected and it was ordered not to leave port. An intrepid young Scotsman was hired and managed to run her out to sea so suddenly there were still workmen on the ship. However, her bearings burned out and the ship drifted to Calais, where it gained entry to port as a ship in distress. Once there, Lieutenant Fauntleroy, CSN, took command of the ship. Trapped in the harbor by two Union warships and French reluctance to allow her to go to sea, the Rappahannock remained there, rotting in its berth until the end of the war.

The Shenandoah– The World-Wide Cruise

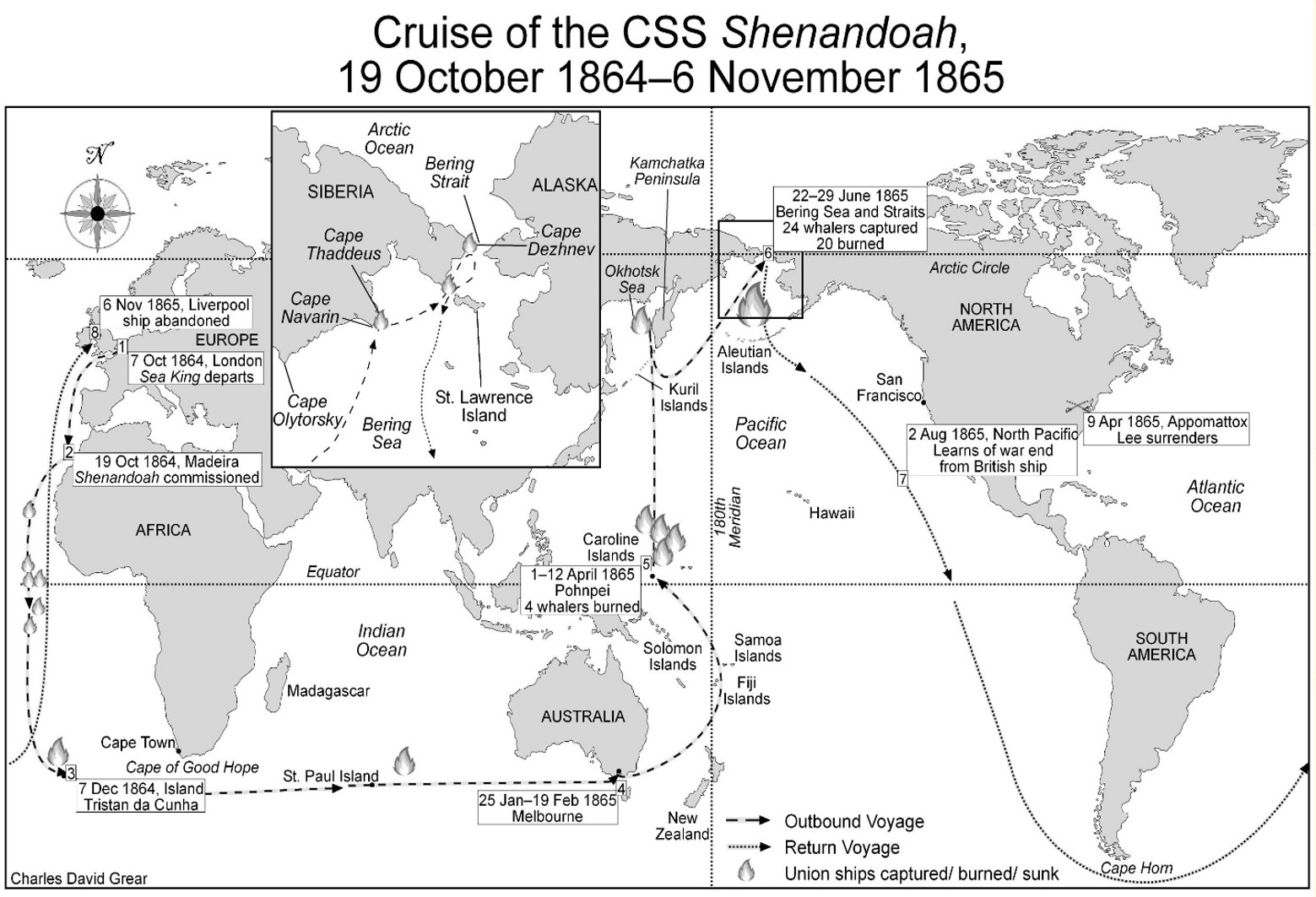

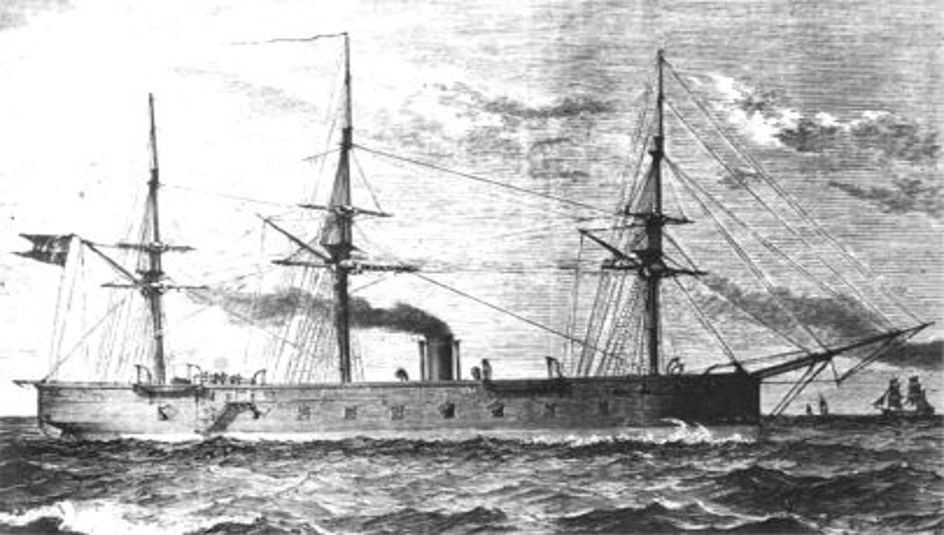

Bulloch purchased the Sea King, a much-admired composite ship in London in September 1864. The vessel slipped past two Union warships guarding the outlet of the Thames and met a tender carrying all necessary arms and war materiel. It was the beginning of a voyage that would take the ship around the globe under her new name, the CSS Shenandoah.

Some of the Rappahannock’s crew was transferred to the Shenandoah, which suffered from personnel shortages throughout its voyage. When it set off on its world-wide cruise, 9 of 23 officers were British, as were all ten petty officers and nearly all the crew. When the ship stopped in Melbourne for repairs, the US consul made repeated complaints that the Shenandoah was recruiting locally in violation of the British Foreign Enlistment Act. Waddell denied all such charges, but after his ship took to sea some 42 “stowaways” emerged, asking to join the crew. Among them were 32 British and two Canadians.

By the time the last great Confederate commerce raider set sail again, boredom and poor morale at sea were becoming major problems due to the lack of prizes since its departure from London. The Shenandoah would literally have to go to the ends of the earth to find them.

Service on the cruisers did allow their crews to see remote places that few other men had seen, such as the visit of the Shenandoah’s officers to the ancient and mysterious stone city of Nan-Matal in the South Pacific. Nearly all the officers received native tattoos in the South Pacific.

Captain James I. Waddell of the CSS Shenandoah

Captain James I. Waddell of the CSS Shenandoah

The Shenandoah was not a happy ship, however; it was continually plagued by bitter rivalries and disputes in its officer corps as well as a general dissatisfaction with its skilled but sullen master. In a sign of declining discipline, the Shenandoah’s officers began to pilfer personal items from their prizes in the South Pacific, blurring the lines between piracy and commerce raiding.

Communicating with a ship deliberately trying to avoid detection was nearly impossible, and the Shenandoah steamed on ignorant that the war at home was quickly drawing to a close.

Bulloch had issued specific orders to Waddell to strike the American whaling fleet in the Pacific, which he described as “a source of abundant wealth to our enemies and a nursery for their seamen.”

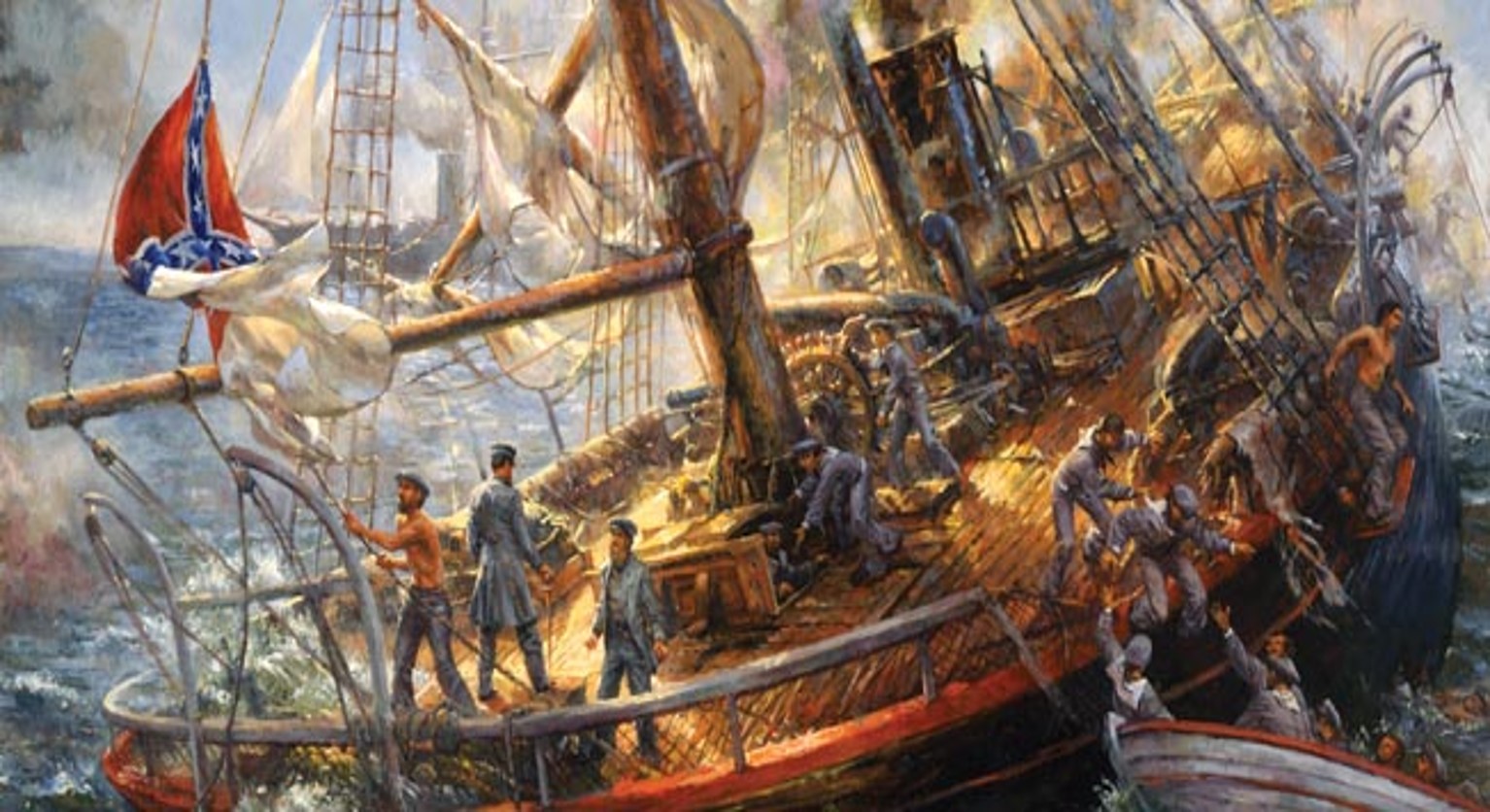

The CSS Shenandoah Burns the New England Whaling Fleet in the Bering Sea

The CSS Shenandoah Burns the New England Whaling Fleet in the Bering Sea

The Shenandoah burned its first New England whaler in the Bering Sea the day after Lee surrendered the Army of North Virginia on April 9, 1865. It was the first of many. One whaler’s captain had lost his first ship to the Alabama, and then another to the Shenandoah; a crewman pledged never to ship with that master again, saying that he was better at finding Confederate cruisers than whales! The Shenandoah fired the last shot of the Civil War on June 28, long after all the other Confederate commands had surrendered. The cruise continued, however, as Waddell was still unaware of the Confederate collapse.

Having destroyed the American whaling fleet, Waddell headed for San Francisco, intending to steam past the formidable harbor defenses at night. Once through, the Shenandoah would ram the Union monitor stationed there, board her, and then turn the guns of both ships against the city to demand its surrender. Before this audacious plan could be put into motion, Waddell finally received definitive proof of the war’s end.

Waddell ordered all the ship’s weapons stowed below. His orders in this case were to sail into Valparaiso, Chile, sell the ship, and pay off the crew. Many of the officers insisted on surrendering the ship to British authorities at Capetown or Sydney, but Waddell instead made the strange decision to take the ship 17,000 miles around the Horn and through Atlantic waters infested with Federal ships.

Newspapers intercepted by the Shenandoah revealed that President Andrew Johnson (Lincoln’s successor) had outlawed the cruiser and that Waddell and his crew were to be summarily hanged as pirates after their expected capture. Despite a near mutiny, Waddell persuaded the bulk of the crew to follow his plan, and, on November 6, 1865, seven months after Lee’s surrender, he sailed the Shenandoah into Liverpool and surrendered her to the city’s astonished mayor. The Shenandoah had captured 38 Union vessels, burning 32 and bonding six on a remarkable cruise of 58,000 miles with stops on every continent save Antarctica.

Newspapers intercepted by the Shenandoah revealed that President Andrew Johnson (Lincoln’s successor) had outlawed the cruiser and that Waddell and his crew were to be summarily hanged as pirates after their expected capture. Despite a near mutiny, Waddell persuaded the bulk of the crew to follow his plan, and, on November 6, 1865, seven months after Lee’s surrender, he sailed the Shenandoah into Liverpool and surrendered her to the city’s astonished mayor. The Shenandoah had captured 38 Union vessels, burning 32 and bonding six on a remarkable cruise of 58,000 miles with stops on every continent save Antarctica.

The Navy that Never Was

By 1863 it had become apparent that the South’s home-made ironclads were capable of individual successes, but were not capable of shattering the Union’s blockade. Mallory decided that ironclads built in Europe would provide the necessary force to drive the blockaders from Southern shores. However, the shallow waters of the Southern coast and ports required shallow-draft ironclads still capable of taking on the Union’s Monitor-class ironclads. The problem was how to get such ships safely from Europe across 3,000 miles of Atlantic Ocean to the Southern states. Bulloch’s plan, never realized, was to ship pre-fabricated shallow-draft warships to the Confederacy for final assembly there.

Instead, Bulloch and other Confederate agents initiated the construction of a powerful, modern war-fleet. This consisted of:

- Two “Laird Rams,” so-called after their builder

- Two French-built rams, Cheops and Sphinx

- Frigate no. 61, “the Scottish Sea Monster”

- Four French-built corvettes.

Two blockade runners under construction in England were to also be equipped with incendiary shells and rockets to launch surprise attacks on New England towns and cities.

The Laird Rams

With 9-inch rifled guns in two revolving turrets, 5.5-inch-thick armor and powerful rams, Bulloch was convinced the Laird Rams would make quick work of the Union’s wooden warships. To deceive Federal spies, it was announced that the two ships were destined for the Egyptian Navy.

Under American threats of war, the British finally agreed to prevent the Laird Rams from sailing out of Liverpool to hoist a Confederate flag. Despite schemes to conceal their ownership, Union spies watching the shipyards had discovered the truth and the rams were eventually purchased by the Royal Navy for use as coastal defense vessels.

“The Scottish Sea Monster” – Frigate no. 61 after its sale to Denmark

“The Scottish Sea Monster” – Frigate no. 61 after its sale to Denmark

At the same time a more advanced and partially armored version of the Alabama under construction on the Clyde was seized. This was followed by the confiscation of “Frigate no. 61,” a powerful ironclad ram built in Glasgow that became known as “the Scottish Sea Monster.” By late 1863, Mallory’s dream of superior European-built ironclads sweeping away a mostly wooden Union war-fleet was beginning to evaporate. Confederate defeats at Vicksburg and Gettysburg had greatly diminished French and British support for the South.

The Stonewall

Two ironclads were built for the Confederates in France in 1864. Also ostensibly destined for the Egyptian Navy, they were named Cheops and Sphinx. Emperor Napoleon III ordered that the still-unarmed ships be sold to neutral powers rather than the Confederacy. The Cheops went to Prussia, where it became the SMS Prinz Adalbert. The poorly-built ship’s short career ended in 1871, when it was discovered that its internal wooden construction had rotted beyond repair.

The Sphinx was sold to Denmark, which rejected her, then sold back to a French firm that in turn sold it to the Confederacy, as originally intended.

Renamed the Stonewall, this ironclad was fitted with a massive ram and a formidable 300 pounder Armstrong rifle mounted in the bow. Many of the crew were veterans of the Florida.

The ship, designed for coastal use, sailed badly in anything other than smooth waters and its junior officers came close to mutiny rather than try to take it across the Atlantic. Storms held it up in European waters long enough for the USS Niagara and the USS Oneida to try and seal it into port. Captain Thomas Jefferson Page, the Stonewall’s commander, took the ironclad out to sea and spent an entire day challenging the pair of Union ships, but they refused to fight. With no apparent opposition, Page took the Stonewall out the next day to cross the Atlantic.

Bulloch was aware of the Stonewall’s weaknesses and its captain was increasingly of the opinion that the ship was being sent on a suicide mission, but Bulloch also knew that the Stonewall’s strength was much exaggerated in the North, and its mere appearance off the North Carolina coast could cause panic in the mostly wooden Union fleet.

The Stonewall as the Japanese Azuma, 1871

The Stonewall as the Japanese Azuma, 1871

In the event, the Stonewall arrived in Nassau just as the Civil War was drawing to a close. Captain Page took the ship to Cuba where he sold it to the Spanish government for just enough money to pay off the crew. The Spanish turned it over to the US for the same amount, which sold it in turn to Japan, where it participated in several battles and gained a reputation as a powerful and unsinkable warship before it was scrapped in 1889.

Post-War Litigation

At war’s end the United States demanded compensation from Britain for the destruction of its merchant fleet. Some US demands, such as receiving Canada in compensation, were viewed in London as excessive. The matter went to arbitration in Geneva in 1872, resulting in a British payment of $15.5 million in gold.

In agreeing to the compensation, Britain made what might have amounted to an admission of culpability when it announced, in diplomatic legalese: “The government of Her Britannic Majesty cannot justify itself for a failure in due diligence on a plea of the insufficiency of the legal means of actions which it possessed.”

It has been argued that Britain actually came out ahead, with most of the remaining American merchant fleet having been re-flagged during the war under the Union Jack. Other unintentional beneficiaries of the commerce raiding campaign were the whales, as the destruction of the New England whaling fleet in the North Atlantic and North Pacific helped hasten the end of whaling as an occupation.

After the war, Confederate naval officers, agents and diplomats involved in commerce raiding were excluded from the general amnesty. Most waited for a second, more inclusive amnesty in 1868 to return to America, though some, like Captain John Maffit, found their property had been confiscated. Bulloch avoided imprisonment by remaining in Liverpool, where he died in near-poverty in 1901. Other naval officers moved to Mexico or Argentina to avoid retribution.

Semmes was arrested and charged with treason, though he was released after four months in prison. His political enemies did not forget him, and succeeded in chasing him from several jobs and appointments. He eventually practiced law in Mobile, where he died in 1877 after eating contaminated shrimp. With time, his reputation improved; Semmes was featured on a 1995 US stamp and portrayed in a full-size statue erected in Mobile in 1900. The statue was suddenly taken down in 2020 in an attempt to appease Marxist Black Lives Matter militants.

Semmes was arrested and charged with treason, though he was released after four months in prison. His political enemies did not forget him, and succeeded in chasing him from several jobs and appointments. He eventually practiced law in Mobile, where he died in 1877 after eating contaminated shrimp. With time, his reputation improved; Semmes was featured on a 1995 US stamp and portrayed in a full-size statue erected in Mobile in 1900. The statue was suddenly taken down in 2020 in an attempt to appease Marxist Black Lives Matter militants.

Conclusion

In the latter days of the war prizes became few and far between, a frustrating development that was actually a tribute to the cruisers’ effectiveness in driving American merchant shipping from the seas. When the Alabama entered Singapore harbor in December 1863, Semmes discovered 20 Union merchantmen lying at anchor, afraid of taking to sea. There were similar scenes in ports across Asia, as insurance rates for American ships sky-rocketed. Union ships that attempted to avoid destruction by changing flags or carrying fake bills of sale to neutral parties rarely fooled the cruiser commanders, who knew every trick.

From the time of the launch of the CSS Sumter, Mallory and Bulloch had made sure that there was always at least one major commerce raider wreaking havoc on Northern shipping somewhere in the world. To cope with this, some 80 Federal warships were diverted from their blockade duties over the course of the war.

Bulloch realized the diplomatic cost of commerce raiding early on, but followed his orders to obtain and equip such ships with enormous energy. The brief reign of the commerce raiders and the litigation that followed spurred greater work on international law that helped reduce many points of friction between the United States and the European powers.

The Confederate commerce raiders could destroy Union shipping or drive it under new flags, but the North, unlike the South, was not deficient in raw materials or the manufacturing base needed to turn these into munitions, weapons, ships and every other type of war materiel. In this sense, it was impossible for the raiders to affect the resource-rich Northern war effort in any significant way. Bulloch was correct in suggesting powerful European-made ironclads capable of smashing the Union blockade were the way to go, if they could be delivered, but he and others eventually learned that no nation, especially one unrecognized, can rely on foreign construction of warships during a conflict to achieve victory.