Andrew McGregor

January 26, 2006

There is little left of the Orthodox Church establishment in Chechnya. Most of Chechnya’s ethnic Russian Christian minority fled in the early 1990s during the creation of Dzhokar Dudayev’s independent Chechen state. The onset of war in 1994 found only the aged and the impoverished remaining of Grozny’s Orthodox population, most of whom suffered greatly in the Russian bombing raids. Grozny’s Church of the Archangel Mikhail, once a symbol of Orthodoxy’s triumph in the Caucasus, is slowly being restored after its destruction by the Russian military in 1995. Reduced to a shell, its congregation consists today of a few hundred aged and hungry pensioners.

Church of the Archangel Mikhail (Grozny)

Church of the Archangel Mikhail (Grozny)

Yet Chechen warlord Shamyl Basayev announced the intention of the “Majlis of the Caucasian Front” to eliminate the “extremist activities” of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Caucasus until the end of the war. In an interview conducted January 9, 2006, Basayev described the church’s leaders as ‘satanists” and accused its clergy of being eager tools of Russian intelligence services (Kavkaz Center, January 9, 2006). The Orthodox Church is finished in Chechnya, but its continuing support for military action in the republic and its efforts at converting Muslims elsewhere in the Caucasus have brought it into conflict with the leadership of the Chechen insurgency.

The Church Militant

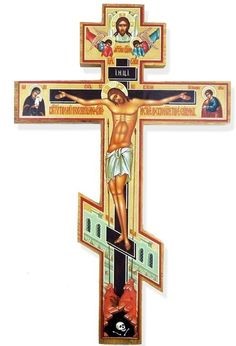

The very emblem of the Orthodox Church, a cross surmounting an Islamic crescent, is a reminder to Russian Muslims that they are a people of conquest, brought into the Russian empire by the force of a united religious and political regime. The renewal of close ties between the church and the post-Soviet Kremlin alarms many Muslims and has been a source of discontent with Muslim conscripts of the Russian army. The leader of the Orthodox Church is Patriarch Alexy II “of Moscow and All Russia,” who has been vocal in his support of the war against “international terrorism” in Chechnya. The Church’s support of the Kremlin has also come with calls for state assistance in restraining the activities of foreign missionaries and the growing threat of “un-Russian” evangelical Protestantism to the Orthodox establishment.

In scenes reminiscent of Tsarist times, long-bearded Russian chaplains hold field services for Russian soldiers, exhorting them to victory over the Muslims before entering battle. Elaborate ceremonies are held in Moscow in which the Patriarch and his bishops confer religious medals to Russian officers for their work in Chechnya. A year into the present Chechen war the Patriarch presented Russian President Vladimir Putin with an icon of Russia’s 13th century hero, Alexander Nevsky, with the hope that the Orthodox saint would become the protector of the President. Alexy speaks of the “unification of the state and the church, the unity (that was) forcibly interrupted by the tragic events of the twentieth century” (Prime-Tass, August 1, 2003).

Russia’s leading political figures can be found as speakers at Orthodox congresses, praising the growing integration of church and government. The Church is especially close to the foreign ministry of Igor Ivanov and supports the reintegration of independent Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan and their large Orthodox populations into the Russian Federation. Ethnic Chechens in Kazakhstan have angrily accused the Orthodox Church there (which is under the control of the Moscow Patriarch) of recruiting ethnic Russians to fight in Chechnya.

A certain amount of Orthodox support for the Chechen war has its origins in the chaotic inter-war period of 1996 to 1999, when Orthodox clergy were frequent victims of violence or kidnapping gangs. Orthodox priests were at the time accused of running a tax-free tobacco and alcohol racket in Chechnya. Russia claims that the Chechen representative in London, Akhmad Zakaev, was involved in the kidnapping and murder of Orthodox clergy, although a British court did not find the accusations credible (particularly after one of his alleged victims was produced alive).

Martyrs of an Orthodox Crusade?

In 2004 the Church bowed to popular pressure and outspoken members of its own clergy by canonizing a young Russian soldier killed in Chechnya. The new saint was Yevgeny Rodionov, a 19-year-old Russian foot-soldier who was captured and beheaded by Ruslan Khaikharov in May 1996. The soldier’s mother, like so many others, went to Chechnya to search for her son’s remains. According to her, she had several meetings with Khaikharov, who revealed that he had killed Rodionov because he refused to convert to Islam. With Khaikharov killed in a Chechen feud soon after, the story remained uncorroborated (and there are many details that make little sense), but this did not prevent the soldier’s grave in Russia from becoming a place of pilgrimage for Orthodox believers. When the church hierarchy declined to canonize the young “martyr,” it came under immense popular pressure from its membership, many of whom claimed that miracles were commonly worked at Rodionov’s grave or that his icons secreted myrrh. There are now several other ‘soldier-martyrs” being considered for canonization.

Basayev has warned in the past that he considered Russian Orthodox churches (with the “defeated Islamic crescent under their crosses”) as legitimate targets of his Riyadus Salihiin Brigade of Martyrs. Two years ago Basayev identified the church’s leadership as members of Russia’s two principal intelligence agencies, the FSB (former KGB) and the GRU (military intelligence), and accused them of taking an active part in “the genocide of the Chechen people” (Kavkaz Center, April, 2004). In Russia itself, accusations of Church collaboration with the KGB date back to Soviet times and are a major factor in the growth of alternative forms of Christianity within Russia.

Since the Beslan massacre the Bishop of Stavropol and Vladikavkaz has been active in encouraging the conversion of North Ossetian Muslims to the Orthodox faith. Basayev must take some responsibility for this as the orchestrator of the terrorist attack that brought repression of those who practice both official and unofficial Islam in North Ossetia (where Orthodox Christians form the majority). Fear of retaliation for the Beslan crime has led to acceptance of the Bishop’s message by Muslims whose adherence to the faith is not as strong as fear for themselves and their families.

Conclusion

Despite the threats, Basayev has not yet targeted establishments of the Orthodox Russian church and is unlikely to do so as long as he adheres to a focus on military rather than terrorist activities currently promoted by the Chechen rebel leadership. Tied to his remarks in the same interview about a renewed Imamate in the North Caucasus, Basayev’s verbal attacks on the Church seem to represent an attempt to define the Chechen struggle in religious terms quite different from the parameters used during the presidency of the late Aslan Maskhadov. The Orthodox Church has acted in a similar fashion, helping to redefine a war against “terrorists” into a war against Islam.

The new Chechen president, Abdul-Khalim Sadulayev, is committed to creating an Islamic state in Chechnya. Basayev suggests that Sadulayev is already “virtually the Imam of the whole Caucasus,” and that a congress will be held this spring to consider the proclamation of Sadulayev as Imam (political/religious leader, in this sense). With Basayev’s encouragement, Abdul-Khalim shows every sign of assuming the mantle of Shaykh Mansur and Imam Shamyl to unify the Islamic opposition to Russian rule in the Caucasus. Basayev’s remarks on the growing symbiosis of the Orthodox church, the Kremlin and Russian security services are meant to remind Russia’s Muslims that Islam presents the only alternative to permanent subservience in a Christian state.

This article first appeared in North Caucasus Analysis 7(4), January 26, 2006