By Andrew McGregor

Behind the Headlines (Canadian Institute of International Affairs), 55(4), Summer 1998, pp.18-23

In the wake of misadventures in Rwanda and Somalia, and a near fiasco in eastern Zaire, Canada is back with a UN peacekeeping mission in Central Africa. What are the prospects for success?

Outside the tight circle of relations between France and the francophone countries of Africa, the words Central African Republic (CAR) usually evoke only hazy, if disturbing, memories of the brutal and farcical reign of `Emperor’ Jean-Bedel Bokassa (1966-79). Though long absent from the sensational headlines that accompanied the Bokassa regime, the CAR is today worse off than it ever was under Bokassa – a financial outcast, ruined by years of government corruption and political instability, and on the brink of sliding into the kind of violent turmoil that engulfs its neighbours.

Following the public relations disasters of Somalia and Rwanda, and a still-born attempt at leading a mission to eastern Zaire, the Canadian government has chosen the CAR as the area for Canadian peacekeepers to return to Africa as part of a francophone peacekeeping mission that may provide the prototype for a much debated Organization of African Unity/United Nations permanent peacekeeping force.

Following the public relations disasters of Somalia and Rwanda, and a still-born attempt at leading a mission to eastern Zaire, the Canadian government has chosen the CAR as the area for Canadian peacekeepers to return to Africa as part of a francophone peacekeeping mission that may provide the prototype for a much debated Organization of African Unity/United Nations permanent peacekeeping force.

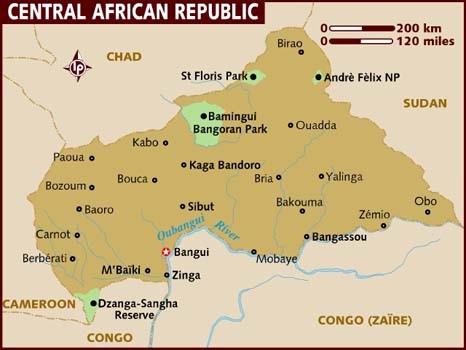

The Central African Republic has known little of independence, democracy, or economic prosperity since it gained statehood in 1960. A land-locked country with few effective trade-links with its neighbours, Ubangi-Chari (modern CAR, Chad, Gabon, and Congo/Brazzaville) was intended by its first leader, Barthelemy Boganda, to be part of a larger post-independence nation comprising all of the former French Equatorial Africa. Boganda believed that a state of this size was necessary for economic viability and envisioned an eventual larger United States of Latin Africa, in which the former colonies of Belgium, France, Portugal, and Spain would be united in Central Africa. Boganda’s dream died with him when his plane exploded in 1959. Since then, the CAR has struggled through the financial dependency and gross mismanagement of David Dacko (twice), Bokassa, General André Kolingba, and the current president, Ange-Felix Patassé.

Effectively managed, the CAR has the potential to be self-supporting, even prosperous. The land is fertile, food plentiful (if poorly distributed), and the population of three million well within reasonable numbers for a country larger than France and the Benelux countries combined. A rich forest and abundant mineral and ore deposits (including diamonds and uranium) await exploitation, but for the moment the nation remains highly dependent upon foreign aid, mainly from France. Government corruption and incompetence placed the CAR on the International Monetary Fund blacklist, but the Fund has agreed to give the nation one last chance to mend its ways in conjunction with the UN peacekeeping mission. The long-neglected development of human resources and the continent’s lowest rate of literacy are two of the greatest impediments to developing a viable economy. Foreign debt is approaching the billion dollar mark, literacy remains rare, 65% of adults make less than US$100 per year, and 75% of children suffer from malnutrition.[1] Life expectancy is a meagre 47 years.[2]

The ethnic composition of the CAR is highly complex and constantly evolving, with some 30 groups displaying a high degree of social and cultural interaction. When describing the population of the Republic, observers often find it convenient to speak of groupings based on environmental adaptation in the three main geographic divisions of the CAR – the savaniers, the riverains, and the forestiers.[3] The last two dominated political life for 33 years, but Patassé’s presidency marked the ascendance of the savaniers. Lately, however, the savaniers are believed to have lost confidence in Patasse, who favours his own Sara group (15% of the savaniers). Patassé is protected by three private militias composed mostly of men from his home district of Ouham-Pendé, supported by Sara rebels from southern Chad who take refuge in Ouham-Pendé, including 1,000 mercenaries called Codos-Mbakaras (`Invulnerable Commandos’). He has also been able to call upon the French-trained Presidential Guard battalion, also recruited from Ouham-Pendé.

Patassé, the leader of the Mouvement pour la Libération du Peuple Centraficain (MLPC), was a prime minister in the Bokassa government. Following two abortive attempts in 1981 and 1982 to seize power from General André Kolingba (who himself took power through a coup in 1981), Patassé was eventually elected president in 1993. Allegations of corruption and tribalism against his government led, in part, to four successive mutinies by the army, which Patassé survived only by invoking a secret assistance pact with France. Nonetheless, he relies upon a platform of anti-French populism and is almost certain to run in the forthcoming presidential elections.

Kolingba remains among some groups a powerful political force with access to funding from wealthy ex-Mobutists who have taken refuge in the CAR. His 12-year rule was notable for corruption and tribalism. Kolingba, a former ambassador to Canada, may contest the elections, but his just as likely to pursue a more direct approach to the presidency. At present, French diplomacy and the UN presence serve to constrain him.

Kolingba is supported by several hundred Zaireans, ex-members of Mobutu’s Division Spéciale Presidentielle (DSP), and may be negotiating for further assistance from mercenaries. French internal security (Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire) has reported a meeting between representatives of Kolingba and Christian Tavernier, a Belgian mercenary who led the ill-fated 1996-97 Serbian mercenary force in Zaire. The 3 April 1998 issue of Africa Confidential claims that Tavernier is eager to sell a mercenary force of Cambodian Khmer Rouge soldiers for use in the CAR. The new corporate-style mercenary firms that were so prominent in the recent Sierra Leone conflict have yet to take an interest in the CAR, aside from making enquiries about former French airbases at Bouar and Bangui for operations elsewhere in Africa.

Most notable among the other possible candidates for the presidency is Abel Goumba, one of the few CAR political leaders who was not compromised by collaboration with the Bokassa regime. Now in his mid-seventies, Goumba leads both the Front Patriotique pour le Progrès and the ‘G-11’ radical opposition alliance. But his democratic credentials are questionable, and there is some feeling in Bangui that his support for the mutinies was opportunistic.

One objective of the UN mission is to remove the CAR army from the political process. Unpaid and under-equipped elements of the army have participated in four abortive mutinies against Patassé that left hundreds of civilians, as well as many mutineers and French Foreign Legionnaires dead. Most of the mutineers are from Kolingba’s Yakoma tribe and are veterans of his Presidential Guard. Patassé’s repeated claim that France armed the mutineers cannot be reconciled with the rapid response France provided to his pleas for help. Most of the balance of the army are Gbaka forestiers (the tribe of Dacko and Bokassa); the almost total absence of savaniers in the ranks explains Patassé’s construction of an alternate security apparatus. At present the army has no command structure, vehicles, or communications equipment, and the security of the country has been left to a gendarmerie of 1500 men and an extremely limited operational capacity. The current demobilization and re-insertion project should retire at least a third of the army, the rest of which Patassé has resolved to build into a multi-ethnic force.

In the face of domestic pressure over intervention on behalf of the unpopular Patassé, the French government created and funded the Misson Internationale de Surveillance des Accords de Bangui (MISAB), a peacekeeping force formed of francophone troops from Chad, Burkina Faso, Gabon, Mali, Senegal and Togo. Authorized by the UN Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter,[4] the force was charged with monitoring implementation of the 25 January 1997 Bangui Agreements. This includes supervising the surrender of arms by former mutineers, militias, and all other persons unlawfully bearing arms. Though MISAB disarmed about 85% of the mutineers, it failed to disarm Patassé’s militias, which led to a widespread belief in Bangui that MISAB were Patassé partisans.

The performance of the multinational force was uneven; some contingents displayed a general indiscipline. Another violent mutiny followed in which 50 people were killed in the crossfire between mutineers, MISAB troops and French helicopter gunships. The 19 June to 9 July mutiny (which had a measure of public support in Bangui) was ended by the mediation of General Amadou Toumani Touré of Mali, who pushed MISAB to be more even-handed in the disarmament process.

Despite its rocky performance, MISAB was seen by the French as a model for inter-African peacekeeping co-operation. France field-tested a prototype eight-nation African peacekeeping force in Exercise Guidimakha between 20 February and 3 March 1998.[5] Unfortunately the exercise served primarily to remind the participants how vital European operational assistance would be to any OAU/UN permanent peacekeeping force. France has shipped a significant amount of military equipment to Senegal for use by such a force and is willing to provide advisors from among officers currently attached to the Senegalese army.

Britain is involved in extensive training of Ghanian peacekeepers, who have substantial UN and Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) experience already. The United States, whose efforts at taking a leadership role in creating an African peacekeeping force were politely rebuffed by several nations (most notably South Africa), has become involved in training and equipping Malian peacekeepers. Nigeria’s former foreign minister, Tom Ikimi (a driving force behind Nigeria’s ECOMOG peacekeeping adventure in Sierra Leone), has denounced the peacekeeping scheme as a neo-colonialist plot to repartition Africa.[6] Nigeria was pointedly left out of plans for creating the force, but the Togolese president, General Gnassingbé Eyadéma, and the OAU secretary-general, Salim Ahmed Salim, have provided enthusiastic support. South Africa’s Nelson Mandela appears to have come on side. He questions the OAU’s strict principles of non-intervention and respect for state sovereignty and suggests that responsible governments have a duty to protect the rights of citizens in neighbouring countries.[7] Amadou Touré, a leader in African conflict resolution, cites le devoir d’ingérence (the duty of interference) in the context of an African village, where a neighbour has the right to step into a dispute between husband and wife, and believes the African tradition needs to be translated into diplomatic action.[8]

A main impetus for the pan-African peacekeeping force is the desire of France to limit its African obligations and roll back the number of troops and bases it maintains in Africa. France has made approximately 35 interventions in the post-independence period, often on behalf of leaders with little international credibility. The recently revealed “secret assistance pacts” with African francophone leaders have been annulled, and a new policy of rescuing only democratically elected governments has been implemented.

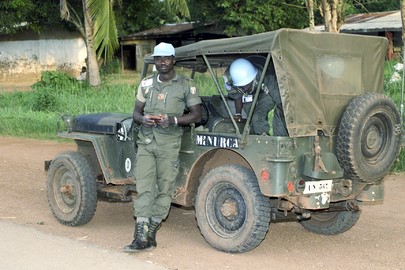

Malian Peacekeepers in Bangui (UN Photo/Evan Schneider)

Malian Peacekeepers in Bangui (UN Photo/Evan Schneider)

The transfer of peacekeeping duties in the CAR from MISAB to the UN’s Mission des Nations unies en République centrafricaine (MINURCA) relieves France of the burden of financial responsibility for MISAB and gives the force added international credibility. Wit Anglophone Ghana dropping out of the original line-up of participants, the new force is essentially MISAB with the addition of small contingents from Canada and Côte d’Ivoire. The leadership of MINURCA was initially offered to Amadou Touré, who turned it down, some think because he wants to be available when a commander for the proposed OAU/UN force is chosen. Field command of MINURCA has been assumed by General Ratanga of Gabon.

The MINURCA mandate is quite specific:[9]

- To assist in maintaining and enhancing security and stability in Bangui and the immediate vicinity;

- To assist national security forces in maintaining law and order in Bangui;

- To supervise and control the disarmament exercise (in practice this has meant arms disposal only);

- To ensure the freedom and security of UN personnel;

- To provide police training; and

- To provide advice and support for legislative elections scheduled for August-September 1998 (since postponed to December and now to be combined with presidential elections).

MINURCA is scheduled to leave 90 days after the results of the elections. Canadian involvement came about as a result of a direct request from th secretary-general of the UN, Kofi Annan, and consists of 45 communications personnel from Canadian Forces Base Valcartier. The Canadians are operating out of the French M’Poko Airbase in Bangui, which will be turned over to CAR authorities when the mission ends. The other French airbase at Bouar was stripped clean by looters after its transfer earlier this year.

Several of the CAR’s neighbours are watching MINURCA’s activities closely. The Rwandans claim that elements of the old Hutu-based Forces Armées Rwandaises and remnants of Mobutu’s DSP are active in the CAR and have launched attacks across the north-eastern Congo against the Rwandans. Chad’s Idriss Déby has recently taken steps to obtain a settlement with the Sara rebels in south Chad to facilitate the early pumping of vast reservoirs of high-grade oil recently discovered in south Chad. Déby would undoubtedly like to see a regenerated CAR army capable of denying CAR territory to Chadian rebels and bandits.

While the Canadian government hopes for a short and successful mission to assert Canadian peacekeeping credentials in Africa, there are few signs to encourage such hopes. With the CAR army largely disarmed and confined to barracks, the countryside has deteriorated into armed chaos. The continued dominance of CAR politics by and old guard of discredited leaders offers only the prolonged use of tribalism and regionalism as the guiding forces of government policy. Just as important as who wins the elections is the question of whether French external intelligence (Direction Générale de la Surveillance Extérieure), a powerful force in CAR politics for many years, abandons it manipulations and leaves Bangui to its own devices.

Regardless of the success of the democratization process, the CAR’s future prosperity will require stable relations with stable neighbours. Unfortunately the CAR remains in the centre of one of the world’s most volatile and faction-ridden areas.. A peacekeeping success in the CAR will be only the first step on a long rad of regional conflict resolution and structural adjustment. To succeed, African leaders must see MINURCA as the start of such a process and not just an attempt by France to pass off responsibility for an unprofitable territory to the UN.

[1] Figures provided in supporting documents for UN Resolution 1159 (1998).

[2] Brian Hunter, ed, Statesman’s Yearbook 1996-97 (London, Macmillan 1996), 333, 1992 figure.

[3] Pierre Kalck, Central African Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1993), xx-xxi.

[4] UN Security Council Resolution 1125 (6 August 1997) authorized a three-month mission to ensure security. On 6 November 1997, a three-month extension was granted by Resolution 1136 (1997).

[5] Exercise Guidimakha was held on the borders of Senegal, Mali and Mauritania. The participating nations were Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, Gambia, Cape Verde Islands, Senegal, Mali and Mauritania. There were also small units from the US Marines and the British Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. Logistics were provided by the French.

[6] Tom Ikimi, speech at an ECOWAS meeting, Lomé, December 1997, quoted in Foreign Report 2485, 26 February 1998, 6.

[7] Nelson Mandela, speech at the 34th OAU Summit, Oaugadougou, 8-10 June 1998.

[8] Kay Whiteman; “A Conversatiion with ATT [Amadour Touman Touré],” West Africa no. 4119, 30 September-13 October 1996, 15611.

[9] UN Security Council Resolution 1159 (27 March 1998).