Andrew McGregor

November 23, 2011

After decades of carrying out unspeakable atrocities and thousands of kidnappings in Central Africa, the elusive commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), Joseph Kony, appears to have narrowly escaped capture by the Uganda People’s Defense Force (UPDF) twice in recent weeks, with the UPDF emerging from the bush with only some of his clothing and his wash basin to show for their efforts (Daily Monitor [Kampala], October 16).

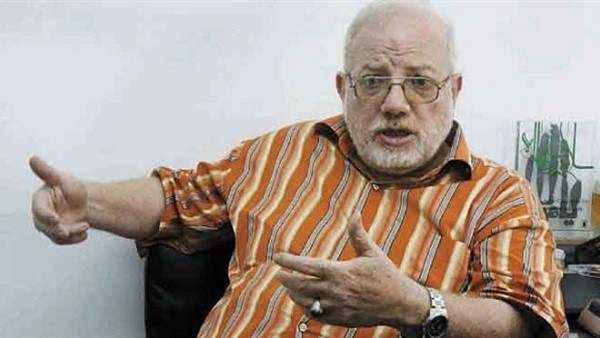

LRA Commander Joseph Kony

Following in the footsteps of the George Bush administration (which once announced elimination of the LRA as an administration priority), President Barack Obama has turned the attention of his administration towards eliminating the LRA by sending roughly 100 Special Forces and other military specialists to aid Ugandan/South Sudanese/Congolese efforts to destroy the dispersed LRA groups still living in the bush of the Central African Republic (CAR) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The deployment has been described as a short term effort that is expected to use lessons learned in the U.S. aided 2009 Operation Lightning Thunder fiasco to protect isolated communities from the LRA while military forces hunt down the group’s estimated 200 remaining fighters. The new weapons to be used against the LRA and its erratic commander, Joseph Kony, are improved communications and military coordination. Villagers will be provided with high-frequency radios to report LRA movements and military commanders from the DRC, South Sudan and Uganda will be given U.S. intelligence gleaned from communications intercepts and satellite imagery (Los Angeles Times, October 25). In addition, both military and civilians will be able to follow the militia’s movements through the “LRA Crisis Tracker” website, funded by U.S. charities (BBC, October 4). [1]

The Acholi Alienation

Kony’s LRA has its roots in the conflict between the Acholi tribe of northern Uganda and other tribes in Uganda’s south that began during the regime of Idi Amin Dada (1971-1979). The Acholi are a sub-group of the Luo people of South Sudan’s Bahr al-Ghazal region who migrated to northern Uganda several centuries ago.

The troubles in Acholiland may be traced back to 1971, when Ugandan president Idi Amin conducted a ruthless purge of Acholi troops in the Ugandan Army. Many of the survivors went into exile, returning to Uganda in 1979 as part of the Tanzanian forces that expelled Idi Amin. A young Ugandan rebel from western Uganda’s Banyankole tribe named Yoweri Museveni was also part of the invading force. A year later Milton Obote returned to power in Kampala, only to preside over atrocities that surpassed anything committed by Idi Amin. Obote unleashed the Acholi troops in the Luwero Triangle region north of Kampala, where they quickly gained a reputation for looting, rape and murder.

By 1985 Uganda was on the verge of collapse, and Obote was overthrown by an Acholi commander, General Tito Okello with the help of fellow Acholi, Brigadier Bazilio Olara-Okello. The general’s rule was short-lived, however, as Museveni broke a pact with his government and seized power, leaving the Acholi troops to flee north to their homeland. Southern troops happily took retribution in Acholiland for the atrocities committed in the Luwero Triangle. By the late 1980s, most Acholi military formations had folded or joined the new religiously inspired Holy Spirit movement led by Alice Lakwena (a.k.a. “The Messenger,” a.k.a. Alice Auma). The young Joseph Kony, who had dropped out of school to become a traditional healer, was also attracted to the movement.

With a mix of pagan and Christian beliefs, Alice Lakwena promised redemption to the Acholi soldiers while organizing them into local defense forces. Ritual observances were intended to make the men bullet-proof, while Lakwena arranged to have them assisted in battle by snakes, bees and legions of spirits while they attacked their enemies in a cross formation. Strategic decisions were often taken while Lakwena was possessed by spirits, including that of an Italian soldier who had been dead for 95 years. On her way to take Kampala, Lakwena was defeated near Jinja. She escaped and died at a refugee camp in Kenya in 2007, aged 50. [2]In the meantime the Acholi and other northern tribes were forced into IDP camps which have helped neutralize the armed opposition to the Museveni regime, but also maintain a high degree of hostility among displace northerners living in miserable conditions towards the government.

With little of coherence emerging from the LRA in terms of political aims and beliefs, it has been left to Acholi living in the international diaspora (especially London) to provide an intellectual/political framework for the LRA’s activities. These exiled supporters of the movement maintain, like Kony, that atrocities are the work of UPDF troops in disguise with the intention of discrediting the LRA. While their statements contain criticism of Museveni’s “one-party rule” and call for Ugandan federalism, free elections and political reform, the Ugandan government has been more successful in providing a counter-narrative that characterizes the LRA leadership as erratic, purposeless and obsessed with bizarre religious beliefs. [3]

The LRA and the Bush Kingdom of Joseph Kony

Kony is known for rapid and continual changes of mood. It is clear that he regards most peace negotiations as a trap or a cover for attack. The barely literate LRA commander is known for delivering a steady stream of convincing sermons with creative interpretations of bible verses that justify his violence. Like his Acholi predecessor, Alice Lakwena, Kony is frequently possessed by spirits.

Kony turns to the Bible for precedents to vindicate his preference for polygamy, abductions and amputations. In particular he cites Matthew 5, 29-30 to defend the common LRA practices of severing limbs, lips and noses: “If your right eye is your trouble, gouge it out and throw it away! Better to lose part of your body than to have it all cast into Gehenna [i.e. hell]. Again, if your right hand is your trouble, cut it off and throw it away! Better to lose party of your body than to have it all cast into Gehenna.” LRA massacres are intended to show that government security forces are incapable of defending the populace. Kony’s three main stated objectives may be described in the following way:

- Impose the Ten Commandments on Ugandan society

- Overthrow the Museveni regime.

Kony’s dreadlocked warriors are forbidden to smoke or drink alcohol. The consumption of mutton, pork (Kony considers pigs to be ghosts) and pigeon are all prohibited. There are also a number of standing orders concerning water, such as a prohibition on shouting while crossing rivers. Total obedience to Kony is mandatory for his fighters but excellent performance in carrying out his wishes is rewarded by the presentation of kidnapped girls. Pre-pubescent girls are a favorite target for abduction due to the belief they are less likely to be infected with AIDS. Male children are abducted to replace fallen fighters, their youth providing a clean slate for Kony to impose his own vision of morality. In the fashion of most religious cults, the LRA now provides these youth with family and purpose. Adults are used for forced labor and may be released or killed when no longer needed – some in the region have been subject to multiple abductions. Due to battlefield losses, desertion and the movement’s extended absence from north Uganda, it is probably safe to say that most members of the LRA now have no connection to the Acholi people.

The local Acholi often support the LRA to earn cash by selling the group marked-up goods or out of concern for abducted relatives. Others support the LRA’s opposition to Museveni, who has very little support in northern Uganda. Supplies of food, arms and other materiel from Khartoum as part of a proxy war with Uganda allowed the LRA to grow in the bush to a force of over 10,000. From their bases in South Sudan the LRA were encouraged to make local attacks against South Sudanese civilians and even to cross the Ugandan border to attack South Sudanese refugee camps there. Thanks to the patronage of Khartoum, the LRA found itself well-armed with a variety of Soviet/Russian made equipment, including recoilless rifles, anti-tank weapons, rocket-propelled grenades, landmines and the ubiquitous AK-47 assault rifle. At the height of the struggle between Khartoum and the Ugandan-backed SPLA, Kony’s group was even allowed to open offices in Juba and Khartoum. [4]

Life is precarious in the LRA, dependent entirely upon Kony’s moods and the current state of his paranoia. The LRA commander killed one of his chief lieutenants, Alex Otti Lagony, in 1999, opening the door to a series of murders of top LRA commanders who no longer had Kony’s full trust. According to Ugandan journalist Billie O’Kadameri, “When you are with him, it’s like he cannot kill a fly, yet he has a reputation as the deadliest of all commanders. He would give orders to kill as if he was giving orders to serve food.” [5] At the same time, however, many ex-members of the movement, including abductees, have spoken of the sense of purpose they found through a movement that gave them ranks and rewards they could never achieve otherwise.

Operation Iron Fist

In 1999, Sudan and Uganda reached an agreement to stop supplying each other’s rebel factions in their long-standing proxy war. However, Sudan’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) continued to supply Kony as Khartoum sought to keep its options alive.

With serious negotiations finally underway in Sudan in 2002 to bring an end to the two-decade old Sudanese civil war, Khartoum gave the Ugandan military permission to pursue the LRA across the border and attack their bases in South Sudan. The operation was not a success, however, with Kony fleeing to the remote Imatong Mountains where his forces massacred 400 people. LRA activities in northern Uganda actually intensified during Operation Iron Fist.

Unable to defeat the LRA in the field, Kampala referred Kony’s case to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in December, 2003. The ICC eventually charged Kony and four others (Okot Odhiambo, Vincent Otti, Dominic Ongwen and Raska Lukwiya) with war crimes and crimes against humanity. The move was opposed by many in northern Uganda who preferred traditional methods of conflict resolution and Kony has repeatedly cited the ICC’s charges of war crimes as the main issue preventing him from coming in from the bush. Once the ICC becomes involved, however, it is nearly impossible to ask it to abandon its prosecution efforts. Under ICC rules, Kampala cannot request the suspension of arrest warrants once issued, even if Uganda were to reverse the ratification of its agreement to sign on to the ICC. In the meantime, attrition seems to be taking care of at least some of the problem; Odhiambo and eight other commanders were massacred by Kony in April 2008, Otti and a number of his followers were killed in a gunfight with Kony loyalists in October, 2007, and Lukwiya was killed by the UPDF in August, 2006. Despite committing a series of horrific crimes, Ongwen (a.k.a. “The White Ant”) has received support from various academics in the West as a “victim” who is not responsible for his actions since he was abducted and integrated into the LRA while only ten-years-old. [6]

Riek Machar meets with LRA Commanders

Operation Lighting Thunder

After the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) took effective control of South Sudan in 2005, it became a priority for the acting government in the southern capital of Juba to drive the LRA out of South Sudan. Kony’s surrender seemed tantalizingly close in April 2008 following several years of efforts by South Sudanese vice president Riek Machar to bring an end to LRA rampages. Kony, however, failed to show up for the signing of the Final Peace Agreement (FPA) after keeping Machar and a number of dignitaries and observers waiting for days in a bush clearing in Western Equatoria (see Terrorism Monitor, April 16, 2008).

In February 2009, Kony led some 200 followers into the southeastern Central African Republic (CAR). With this area effectively out of the control of the weak central CAR authorities the UPDF was invited in to eliminate Kony’s group, which had begun using a base at Gbassiguri for raids into South Sudan’s Western Equatoria province (New Vision [Kampala], February 27, 2009; September 7, 2009). The LRA was also quick to attack its new neighbors, abducting over 100 children and adolescents from the CAR village of Obo in March, 2009 (Daily Monitor [Kampala], March 12, 2009; April 10, 2009). Fighting in Western Equatoria between the LRA and the local “Arrow Boys” self-defense groups became increasing brutal. With the LRA short on ammunition, Kony’s fighters used amputations and mutilations to terrorize the local population while the Arrow Boys began treating LRA captives in kind (Sudan Tribune, March 6, 2009).

Like the earlier Operation Iron Fist, Operation Lightning Thunder only succeeded in making things worse. Backed by American advisers working out of Uganda, the operation was a major undertaking by the armed forces of Uganda, South Sudan and the DRC. As the shattered LRA scattered into the thick bush the pursuing militaries lost most of the tactical advantages provided by better arms and equipment, finding themselves reduced to splitting up into platoon-sized groups hunting even smaller groups of LRA through the DRC’s Garamba Forest. Groups of LRA fugitives expressed their displeasure at being chased by their usual methods of massacre, mutilation and abduction in the isolated communities of the eastern DRC. As the operation ground to a close in mid-2009, it was generally recognized as a setback in the elimination of the LRA rather than a triumph, despite the elimination of most of the LRA’s bases and several of its leaders.

The SPLA, however, had not given up on the hunt for Kony, and decided to deploy its Special Forces in the hunt for Kony. In Juba it was widely believed that the ruling Islamist National Congress Party (NCP) was continuing to provide covert aid and assistance to the LRA (Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 4, 2009; see also Terrorism Monitor Brief, September 10, 2009). In December, 2009 LRA forces under the command of Dominic Ongwen are believed to have been responsible for the massacre of roughly 300 civilians in the DRC village of Makombo after locals objected to acts of rape, murder and hundreds of abductions carried out by the group (New Vision, March 28, 2010; Daily Monitor, March 29, 2010). [7]

Conclusion

Kony’s forces no longer fight on behalf of the Acholi, nor do they fight in their interests. Forced from Uganda and their bases in Sudan, the sole remaining cause of the LRA is the preservation of the LRA. The vague ideology of the movement has always served as little more than a mask for the personality cult surrounding Joseph Kony despite the efforts of some to cloak the movement in the guise of Acholi liberation. To fight, to murder, to mutilate – these are ways to satisfy Kony and live to kill another day. The rewards for loyalty and success are tangible, while the penalty for failure and disloyalty is an ever real threat.

Despite being one of the world’s most incommunicative rebel leaders and never having shown particular indications of ideological brilliance, Kony has nevertheless survived by masterfully manipulating those who would seek to use him, whether as a pawn in Sudan’s civil war or as a means of maintaining just the right amount of insecurity in the expanding military state of Uganda. American military cooperation for the Ugandan effort against the LRA will further cement ties between the two militaries, which already cooperate closely in Somalia.

Both the war in Uganda and the aid programs that sustain it have become a kind of industry. The Ugandan Army is very much a profit-making institution, whether through diverting public funds to provide for thousands of “ghost soldiers” (in which arms, food, clothing and salaries for non-existent troops are collected by corrupt officers for resale, sometimes to the LRA), or through the exploitation of natural resources in areas where the Ugandan Army operates, such as the teak wood of South Sudan or the minerals of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Efforts have even been made to tie the LRA to the wider global “War on Terrorism” in an attempt to tap U.S. funding for counterterrorism campaigns; according to Robert Masolo, the Directorf-General of Uganda’s External Security Organization (ESO), Osama bin Laden trained “the LRA into killer squads in Sudan, along with other al-Qaeda terrorists…” (New Vision, June 12, 2007).

The continuing threat posed by Kony’s LRA helps preserve the Museveni regime and the Ugandan military budget. Northern victims of the LRA now gathered in IDP camps have never supported Museveni or his party, so there is little political cost inside Uganda for a prolonged counter-insurgency. Peace talks have often been interrupted by government attacks or offensives, often on the grounds that Kony was using the talks to regroup or re-arm. Kony has also walked out of many negotiations, some of which seemed frustratingly close to bringing an end to the LRA’s depredations. However, the introduction of new tracking technology and military assistance from U.S. Special Forces may soon spell the end of Joseph Kony unless the “spirits” that possess him can once more save the LRA leader from imminent destruction.

Notes

1. http://www.lracrisistracker.com/.

2. Heike, Behrend, Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirits, War in Northern Uganda, 1985-97, Ohio University Press, 2000.

3. Mareike Schomerus, “The Lord’s Resistance Army in Sudan: A History and Overview,” Small Arms Survey, Geneva, 2007.

4. Matthew Green, The Wizard of the Nile: The Hunt for Africa’s Most Wanted,: London, 2008, p. 175.

5. Quoted in Green, 2008, p.186

6/ See the statement of University of British Columbia professor Erin Baines, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56XadQ32lkw, and “Complicating victims and perpetrators in Uganda: On Dominic Ongwen,” Justice and Reconciliation Project Northern Uganda/ Liu Institute for Global Issues Field Note, 7 October 2008, http://www.humansecuritygateway.com/documents/JRP_dominicongwen.pdf.

7. See http://lracrisistracker.theresolve.org/media/video/makombo-massacres.

This article first appeared in the November 23, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Militant Leadership Monitor.