Andrew McGregor

From Tips and Trends: The AIS African Security Report, March 2015

Chadian Troops in the Field in Mali

Chadian Troops in the Field in Mali

In a six-week campaign, Chad’s military has mounted an air-supported ground offensive against Nigeria’s Boko Haram militants that has crossed into both Nigeria and Cameroon. In the process, Chad has shattered Boko Haram strength in the Lake Chad border region but now finds further progress stalled as Abuja denies permission to pursue the fleeing gunmen further into Nigeria. With Chadian operations having scored major successes against Boko Haram, there is now a danger the still inefficient Nigerian military will attempt to take over operations on its own territory to bolster the electoral chances of Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan, who faces an election on March 28.

Chad’s Military Intervention in Nigeria

A brigade size group (1500 to 2000 men) was sent with some 400 military vehicles to the Lake Chad border region on January 16, 2015. The legal framework for Chadian intervention in the region was already established by the 1998 agreement between Chad, Nigeria and Niger to form a Multinational Joint Task Force (MJTF) to combat cross-border crime and militancy. Since their arrival in January, Chad’s military has reported a series of spectacular, if numerically unverifiable victories, including a battle at Gambaru in which the army reported the death of 207 Boko Haram militants to a loss of one Chadian soldier killed and nine wounded (Reuters, February 25, 2015) [1]. Nonetheless, the poorly coordinated offensive is still taking a toll on Boko Haram, reducing its strength and expelling it from towns (and economic support bases) taken in recent months. Boko Haram counter-attacks persist, but most are driven back without great loss.

- On January 29-30, Chadian forces crossed into Nigeria for the first time, using jet fighters and ground forces to drive Boko Haram fighters from the village of Malam Fatori in Borno State after a two-day battle (ThisDay [Lagos], February 1, 2015; Daily Trust [Lagos], January 30, 2015; al-Jazeera, January 30, 2015).

- On January 31, 2015, Chadian forces reported killing 120 Boko Haram fighters in a battle in northern Cameroon centered around the town of Fatakol and used two fighter jets (most likely Sukhoi Su-25 recently obtained from Ukraine) to bomb the Nigerian town of Gambaru (Reuters, January 31, 2015; AFP, January 31, 2015).

- On February 3, Chadian troops backed by armored vehicles took Gambaru after a fight of several hours (Independent, February 4, 2015). One Chadian battalion commander who took part in the attack on Gambaru had little praise for the Boko Haram fighters that had resisted months of Nigerian operations in the area, saying “yesterday’s offensive made us realize that the fighters of the sect, mainly composed of minors, are only cowards” (Alwhihda [N’Djamena], January 30).

The rapid success of Chadian forces against Boko Haram fighters in the border region revealed the sham war that Nigeria’s military has mounted against the Islamists – Malum Fatori, for example, had been held by the militants since October, even though it fell to the Chadians in one day. Chad has succeeded by using aerial bombardments on Boko Haram targets prior to massive assaults with ground troops and armor. These tactics stand in contrast to those of the Nigerian military, which has become notorious for poor ground-air coordination and failing to press attacks, often citing inferior arms or ammunition shortages. Nigerian warplanes were blamed for the death of 36 civilians when two fighter-jets attacked a funeral party in the Niger border town of Abadam on February 17 (Reuters, February 18). [2]

Nigeria – No Longer a Regional Military Power

Nigeria’s foreign minister, Aminu Wali, has tried to explain why Nigeria requires international assistance in combatting Boko Haram:

It is not that the Nigeria army isn’t fighting, it actually is. But in the context of an unconventional war, that is something else. The same thing applies to the war on terror. So the conventional armed forces aren’t adapted to this kind of conflict. We have to retrain them so that they will be capable to fight this particular conflict that they’ve never known before (RFI, January 30, 2015).

In October 2014, Chad, Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon agreed to coordinate their military efforts against Boko Haram, though follow-up was slow. Nigerian relations with Cameron have been historically strained by rival claims to the Bakassi Peninsula in the resource-rich Gulf of Guinea, which was eventually awarded to Cameroon through international arbitration in 2009. Since then, Cameroonian oil infrastructure in the region has been subject to attacks by a hybrid criminal/separatist movement seeking unification with Nigeria.[3]

Since the joint offensive began, Nigerian military performance has improved, which the government chalks up to newly purchased arms and Special Forces reinforcements being sent to help the ill-equipped, poorly-led and occasionally mutinous Nigerian 7th Division, which took over responsibility for the sector from the Nigerian Joint Task Force (JTF) in August 2013 (at one point troops of the 7th Division’s 101st Battalion fired at former division commander Major-General Ahmadu Mohammed, who only narrowly survived – see ThisDay [Lagos], May 16, 2014). The retaking of Baga by Nigerian troops on February 21 deprived Boko Haram of a major base and gave a boost to the political fortunes of President Goodluck Jonathan, but the town could have been taken weeks earlier if the Nigerian Army had not rebuffed Chad’s offer of a joint offensive, according to Chadian Army spokesman Colonel Azem Bermandoa (Reuters, March 3, 2015). Baga was the scene of a firefight in April 2013 in which the JTF and Boko Haram displayed a callous disregard for the lives of civilians in the town, killing over 185 people. The town was taken by Boko Haram in January 2015 when fleeing Nigerian troops allowed the militants to massacre hundreds of civilians (BBC, February 2, 2015).

Northeast Nigeria – Zone of Chadian Operations

Northeast Nigeria – Zone of Chadian Operations

Colonel Bermandoa has likewise complained that Chadian forces took the ancient Nigerian town of Dikwa in mid-February but were ordered by the Nigerians to evacuate it so the Nigerians could launch an airstrike on the community. Chadian forces were compelled to retake the town on March 2 at a cost of one dead and 34 wounded (AFP, February 19, 2015; Reuters, March 2, March 3, 2015; Premium Times [Lagos], March 2, 2015; RFI, February 3, 2015).

Cameroon and Niger have played secondary but important roles in the offensive, pouring their forces into their border regions where they have repulsed attacks, cut supply routes and prevented Boko Haram fighters from slipping away across the borders.

Why Chad is Fighting in Nigeria

Landlocked Chad’s main trade routes cross through areas of Nigeria and northern Cameroon that have been blocked by Boko Haram occupation and operations, leading to shortages of goods (including food from Nigeria), interruption in the important export trade in Chadian cattle and rapidly rising prices for most goods (Wall Street Journal, February 26, 2015).

Economic effects have also been felt in northeastern Nigeria, where the important supply of smoked fish from Lake Chad has been disturbed as a consequence of trade routes being cut by the militants and the fear of fishermen on the Nigerian side of the lake that they will be conscripted into Boko Haram, resulting in shortages and soaring prices for fish in Nigeria (AFP, February 25, 2015).

Boko Haram leader Abubakr Shekau threatened to launch a war against Chad, Cameroon and Niger in a January 2015 video in retaliation for their alleged pro-French sympathies. The Boko Haram leader also took the opportunity to mock the Nigerian military, which has long complained a lack of equipment and arms is preventing them from properly engaging Boko Haram:

All this war equipment that you see being displayed in the screen are gotten from [the captured Nigerian towns of] Baga and Doro. Your army kept deceiving the world that you can’t fight us because you have no arms. Liars! You have all that it takes; you are just coward soldiers (Premium Times [Abuja], January 21, 2015).

In late January, Boko Haram spokesman Abu Musab al-Barnawi used a video to issue new threats to Chad and its MJTF partners:

We say to Niger and Chad that if they stop their assault on us and we will stop our assault on them; otherwise, just as you fight us we will fight you. We will inflame a war of which you have not before tasted its bitterness. Withdraw your soldiers before you regret what will come soon and you have no time to regret. (Premium Times [Lagos], January 28, 2015).

Boko Haram made its first attack on Chadian soil on February 13, using motorized canoes to set a fishing village on fire before being repulsed by Chadian soldiers in what the local Chadian governor described as a “publicity stunt” (Reuters, February 13, 2015).

Most Boko Haram members, including its leaders, belong to the once powerful Kanuri community whose former Bornu Empire straddled the modern borderland between Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon and Niger. Though most of Boko Haram, including its leadership, are Kanuris, most of the militant group’s victims have also been Kanuri, dispelling any notion that the Islamist movement somehow represents the Kanuri community. Nonetheless, it is clear that Boko Haram members have been able to utilize family ties and other types of kinship to facilitate the cross-border movement of arms, supplies and personnel across local borders. Given this cross-border movement, it seems likely that Chadian security forces will have a close look at the local Kanuri community in southern Chad during their deployment in the region.

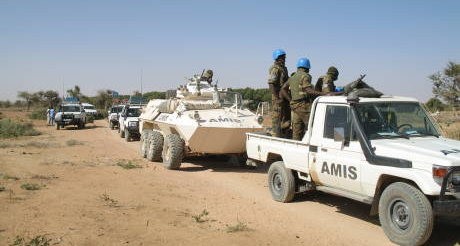

Keeping the military busy in the south may also appeal to the Déby regime; the last attempt by factions of the military to mount a coup was less than two years ago, while Déby himself came to power in a 1990 coup. However, continuous deployment to various theatres runs the risk of internal military breakdown and Chad is already committed to maintaining 1,000 men of its small army in Mali as part of UN peacekeeping operations.

Aware of the danger of reciprocal attacks from Boko Haram, Chad’s security forces have stepped up security, mounting roadblocks, securing the entrances to the capital, N’Djamena, guarding assembly points such as schools, markets and places of worship and rounding up suspected Boko Haram sympathizers in N’Djamena. Many of those arrested belong to the Kanuri community, though Interior Minister Abderahim Bireme Hamid insists that “The arrests are not targeted at a particular social group or community, but those suspected of being close to Boko Haram” (Xinhua, January 28, 2015).

Prior Performance in Military Interventions

Chad’s expeditionary force in Mali performed well in 2013 and did much of the fighting to expel the various armed Islamist groups that had seized northern Mali. However, heavy losses from ambushes and suicide bombings compelled President Déby to announce he was withdrawing the Chadian contingent because “The Chadian army does not have the skills to fight a shadowy, guerrilla-style war that is taking place in northern Mali” (Reuters, April 14, 2013).

Some observers have contrasted the Chadian military’s performance in Mali with their more controversial intervention in the Central African Republic from 2013-2014, where they were accused of political manipulation, arming the Séléka [4] rebels and brutality towards the non-Muslim population that culminated in the massacre of 30 unarmed civilians and the wounding of 300 others when they opened fire on a crowded Bangui market without apparent provocation. [5]

While there was much that was questionable and even indefensible in the performance of Chad’s army in the CAR, it must be recognized that the troops were carrying out N’Djamena’s own agenda in the country, which both modern Chad and pre-colonial sultanates in that region have always regarded as a political and economic hinterland (and prime source of slaves for Chad’s pre-colonial Islamic sultanates) whose rulers were determined by their northern neighbors. In this case, Déby pursued an agenda that involved installing a pliant, Muslim-dominated government in the CAR that would secure the oilfields of southern Chad and prevent opposition forces from using the CAR as a staging-post. Ultimately, pursuit of this policy led to large-scale protests against the Chadians in Bangui and the withdrawal of the Chadian mission.

Chad – A Growing Military Favorite of France and the United States

Chad’s more serious approach to military development and reform has attracted the support of the United States, which now finds serious flaws in its former Nigerian security partner. U.S. training programs and arms sales have broken down in recent years as a result of American concerns with human rights abuses, corruption in the officer corps, infiltration of the Nigerian security forces by Boko Haram and the failure of Nigerian forces to act on U.S.-supplied intelligence (New York Times, January 24, 2015). American concerns with infiltration are not unjustified; a number of senior Nigerian officers have been charged with divulging intelligence to Boko Haram.

Chad is currently host to Flintlock 2015, this year’s version of Flintock, a U.S.-led multinational military exercise conducted by Special Operations Command Forward – West Africa in the interests of improving cooperation and capacity in Saharan counter-terrorism operations. The three-week exercise, which began on February 16, involves more than 100 soldiers from the U.S. 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) as well as trainers from a number of Western nations.

Though President Déby was publicly musing about expelling all French troops from Chad only a few years ago, there has since been an about face on this policy, with Chad welcoming a boost in French forces as part of France’s major redeployment of its military forces in Africa, a shift in focus to mobile counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency units and bases known as Operation Barkhane. As part of this redeployment, French forces in Chad were boosted from 950 to 1250 men, with N’Djamena providing the overall command center at Kossei airbase, with two smaller bases in northern Chad at Faya Largeau and Abéché, both close to the Libyan border. Chadian opposition parties and human rights organizations were dismayed by the new agreement, which appears to legitimize and even guarantee the continued rule of President Idris Déby, who has held power since 1990 (RFI, July 19).

France is currently mounting reconnaissance missions in the Lake Chad border area and is supplying intelligence, fuel and munitions to the military coalition as well as providing ten military specialists to help coordinate military operations from Diffa in Niger (Reuters, February 5, 2015).

Despite the presence of roughly 200 ethnic groups in Chad, the military continues to be dominated by members of President Déby’s northern Zaghawa group despite being only somewhere between 2 to 4% of the population. This situation, however, seems to trouble President Déby more than it does his French and American allies.

The MJTF is slated to be replaced by an expanded and African Union-mandated version of 8750 men that will include troops from Benin as well as Chad, Nigeria, Niger and Cameroon. Logistical and intelligence support will be supplied by France and the United States. Command of the new force will rotate amongst member nations, beginning with Nigeria. The force is proposed to include the following contributions of troops: Nigeria 3500; Chad 3500; Cameroon 750; Niger 750; Benin 250 (BBC, February 25, 2015). A mandate for the mission from the UN Security Council is being sought with French support; this would provide greater funding and access to equipment and training.

Conclusion

If Chad succeeds where Nigeria failed, the result might be a collapse in confidence in Nigeria’s federal government leading to a further break-up of the country as various regions and ethnic groups seek to provide for their own security. The trick will be how to integrate Nigerian forces into the multinational group’s operations despite a well-deserved lack of confidence in the Nigerian military’s ability to mount operations or safeguard intelligence, especially in the midst of a Nigerian presidential campaign pitting a northern Muslim against the southern Christian incumbent. At the moment, there is little cooperation between the various militaries in the Lake Chad region as each continues to operate largely independently – a state of affairs Abuja appears to favor. This appears to be a Nigerian vote in favor of continuing the regional status quo, in which multilateral cooperation is lacking, trade minimal and effective transportation networks so absent that it is impeding the struggle against Boko Haram. As one recent report noted, “it is still easier to fly to Europe from Nigeria than to any of Chad, Niger and Cameroon.” [6]

Given the resilient nature of Boko Haram, its appeal to local religious extremists and its growing connections to the international jihadi community, it is worth asking whether the Chadian deployment will have to be open-ended in order to prevent a Boko Haram revival even in the event current operations destroy existing militant formations. Nigeria’s military will not become reliable or capable overnight regardless of what types of weapons the government obtains during its current buying campaign from international illegal arms markets. An extended stay will be expensive for N’Djamena, which is suffering from a sharp decline in oil prices, but if the costs are covered by the West and compensation is offered in terms of French and American advanced training and arms for the elite corps of the Chadian military, the prospect might take on a greater appeal for Déby and his Zaghawa-dominated regime. However, Chad’s army remains small, and the current tempo of operations cannot be maintained for long. There is a window of opportunity now for the destruction of Boko Haram, but it is slowly being shut by political considerations in the Nigerian capital.

Notes

1. Boko Haram spokesman Abu Musab al-Barnawi recently described the Hausa-language term “Boko Haram” (loosely translated as “Western education is forbidden”) as a media invention designed to denigrate the Islamist movement, which he insisted be described in future using its full and official name: “We say that we did not name ourselves “Boko Haram. “Our call is not limited to prohibiting foreign schools and democracy. We are Jama’at Ahl al-Sunnah Lil Dawa wal Jihad. Therefore, this name [Boko Haram] is an attempt to bury the truth. We carry out the support for the Sunnah and establish governance of Allah in the land” (Premium Times [Abuja], January 21, 2015).

2. An amateur video purporting to show a hot firefight between Chadian troops and Boko Haram fighters can be seen at a pro-Chadian government news-site: http://www.alwihdainfo.com/L-armee-tchadienne-enchaine-d-ecrasantes-victoires-le-Nigeria-predit-la-fin-de-Boko-Haram_a15031.html Though there is the continual sound of gunfire it is difficult to tell whether any of the rounds are actually incoming. There are no apparent Chadian casualties despite the failure of many of the soldiers to seek any kind of cover; at one point a soldier crosses in front of the Chadian firing line without suffering harm. More credible video of Chadian operations in Nigeria can be seen at: http://www.france24.com/en/20150219-video-chadian-army-clashes-with-boko-haram-nigeria/

3. For the Bakassi dispute, see: Andrew McGregor, “Cameroon Rebels Threaten Security in Oil-Rich Gulf of Guinea,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor 8(43), November 24, 2013, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=37208&no_cache=1#.VPDWei5cvfY

4. Séléka was a coalition led by the now-exiled Michel Djotodia and composed of the following groups: Front démocratique du peuple centrafricain (FDPC – led by General Abdoulaye Miskine [real name Martin Koumtamadji], a career rebel/freebooter in the Chad/CAR border region); Convention des patriotes pour la justice et la paix (CPJP); Union des Forces Démocratiques pour le Rassemblement, UFDR; Convention Patriotique pour le Salut du Kodro (CPSK); and the Alliance pour la renaissance et la refondation (A2R).

5. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, Press briefing notes on Central African Republic and Somalia, Geneva, April 4, 2014, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14471&LangID=E

6. Onyedimmakachukwu, “It’s Time for Lake Chad Countries to Move from War Comrades to Business Partners,” February 24, 2015, http://www.ventures-africa.com/2015/02/its-time-for-lake-chad-countries-to-move-from-war-comrades-to-business-partners/