Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, January 28, 2018

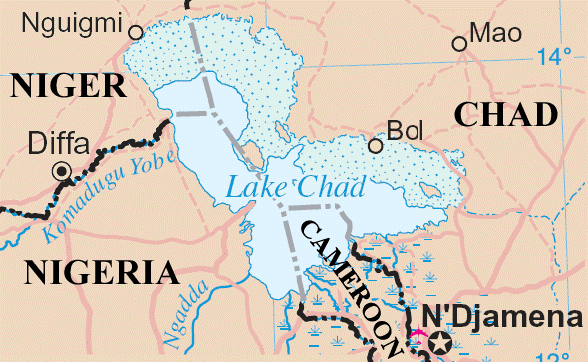

In recent weeks, the Nigerian military has liberated thousands of civilians from the rule of the Islamic State-allied Boko Haram movement, a divided insurgent group now in its eighth year of a callous and merciless effort to impose an extreme form of Islamic rule on northern Nigeria and the Lake Chad region. Hundreds of former Boko Haram militants were released this month after passing through a controversial de-radicalization and rehabilitation program, but both factions of the movement continue assaults on civilians and security personnel in northeast Nigeria and the neighboring states of Niger and Cameroon. Some of the alleged success of the Nigerian military campaign in recent weeks has been attributed to a change in command of Operation Lafiya Dole (Hausa – “Peace by all means”), the codename for Nigerian military efforts to destroy the insurgents.

A Change of Command

The AIS Special Report of July 29, 2017 reported how Major General Ibrahim Attahiru, the commander of Operation Lafiya Dole, had been given a 40-day deadline to take Boko Haram leader Abu Bakr Shekau, dead or alive. [1]

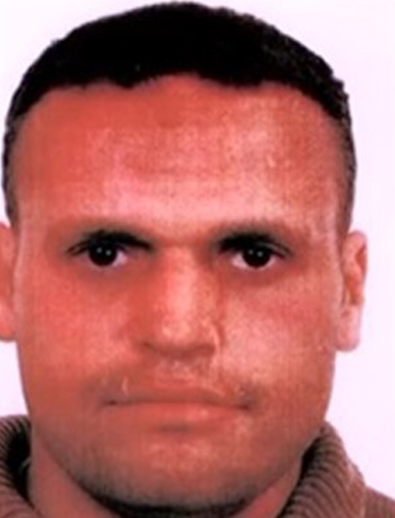

Major General Ibrahim Attahiru (BBC)

Major General Ibrahim Attahiru (BBC)

On December 3, 2017, General Attahiru was relieved of command of Operation Lafiya Dole and redeployed to Nigerian Army HQ as deputy chief of policy and plans. The Nigerian press cited Defense Ministry sources that the change in command was related to poor performance in the field and the inability to catch Shekau (Daily Post [Lagos], December 6, 2017; Punch [Lagos], December 7, 2017).

In the two weeks prior to Attahiru’s transfer, Boko Haram killed 13 people and injured 50 in twin suicide bombings in Biu (Borno State), killed 50 people in a suicide bombing on a mosque in Mubi (Adamawa State) and attacked a forward operating base (FOB) in Magumeri (Borno State), killing three members of the 5th Brigade garrison (8th Division) (Vanguard [Lagos], December 7, 2017; Daily Post [Lagos], November 21, 2017).

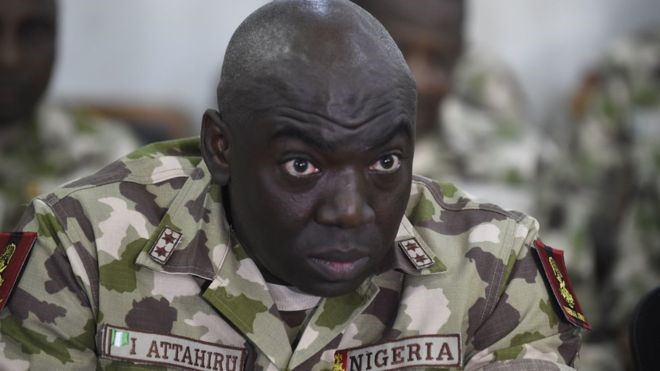

Major General Rogers Ibe Nicholas (Daily Nigerian)

Major General Rogers Ibe Nicholas (Daily Nigerian)

Replacing Attahiru as commander of theater operations was Major General Rogers Ibe Nicholas, the former chief of logistics at Army HQ. Major General Leo Lucky Irabor, who commanded Operation Lafiya Dole prior to General Attahiru, continues as Force Commander of the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) combating Boko Haram. The MNJTF, with headquarters in N’Djamena, includes troops from Benin and the four nations bordering Lake Chad, Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon and Chad.

MNJTF Commander Major General Leo Lucky Irabor

MNJTF Commander Major General Leo Lucky Irabor

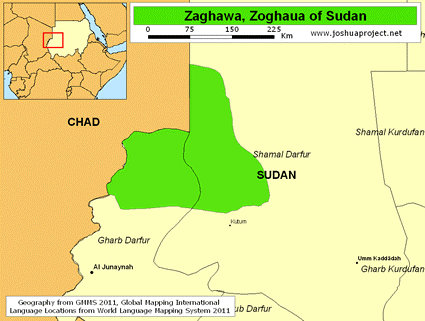

Born in 1962, General Nicholas is an Igbo Christian from southeastern Imo State. Nicholas has experience in the Lake Chad Basin, where he was stationed as a young officer. He has also served in the Nigerian contribution to the joint UN/African Union peacekeeping mission to Darfur (UNAMID) and is the former commander of Operation Safe Haven in Plateau State. Well educated, Nicholas speaks Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa, English and French, has two Master’s degrees, a post-graduate degree in public administration (all obtained in Nigeria) and is a chartered public accountant (Daily Nigerian, December 11, 2017).

Two weeks after his appointment, General Nicholas warned his officers that they would be punished if they did not take their tasks seriously, adding: “We have been losing our equipment and men to Boko Haram. I cannot tolerate this. We must go out to this people once and for all and show them the might of the Nigerian military. We must make sure we defend this nation with the last drop of our blood. We must not lose anything to these insurgents again. We have no other country but Nigeria and we must fight for it” (Punch [Lagos], December 17, 2017).

General Nicholas also emphasized that Operation Lafiya Dole could not succeed if it was solely a military operation, noting that success required cooperation with police, immigration and customs authorities as well as the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF, a local vigilante militia) in order to restore civil authority in liberated regions (This Day [Lagos], January 4, 2018).

Nigerian Army operations in the northeast have been complicated by the split in Boko Haram that occurred in August 2016 when the Islamic State leadership moved to replace the erratic Abu Bakr Shekau with the young Abu Mus’ab al-Barnawi. Boko Haram had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in April 2015. Shekau ignored the order to step down and the movement split into two groups; one commanded by Shekau in the Sambisi Forest and the other under al-Barnawi and his lieutenant Mamman Nur in the Lake Chad area. [2]

A Defeated Insurgency?

The New Year ushered in a wave of optimism to Nigeria’s military and political leaders. On January 6, the Nigerian military announced Boko Haram operational commander Mamman Nur had been “fatally injured” by a Nigerian bombardment in the Lake Chad region, though it did not explain the term “fatally injured” nor how it had identified Nur as a casualty. One of Nur’s wives was said to have been killed in the action while hundreds of militants surrendered to take advantage of Operation Safe Corridor, a de-radicalization and reintegration programme. Others were said to be fleeing to Niger to accept a government amnesty offered there (Premium Times [Abuja], January 6, 2018; Punch [Lagos], January 6, 2018; This Day [Lagos], January 7, 2018).

Following the bombardment, chief of army staff Lieutenant General Tukur Yusuf Buratai declared: “I want to assure you without mincing words that the Boko Haram terrorists have been defeated, all we are fighting for now is the peace in the northeast” (The Nation [Lagos], January 8, 2018). Buratai told troops of the Nigerian 8th Task Force Division based in Borno State that the division would soon be redeployed to Sokoto State in northwest Nigeria (Guardian [Lagos], January 8, 2018). The movement to Sokoto was first announced in November 2016, conditional on the completion of 8th Division anti-Boko Haram operations in Borno (Premium Times [Abuja], November 27, 2016).

Following the bombardment, chief of army staff Lieutenant General Tukur Yusuf Buratai declared: “I want to assure you without mincing words that the Boko Haram terrorists have been defeated, all we are fighting for now is the peace in the northeast” (The Nation [Lagos], January 8, 2018). Buratai told troops of the Nigerian 8th Task Force Division based in Borno State that the division would soon be redeployed to Sokoto State in northwest Nigeria (Guardian [Lagos], January 8, 2018). The movement to Sokoto was first announced in November 2016, conditional on the completion of 8th Division anti-Boko Haram operations in Borno (Premium Times [Abuja], November 27, 2016).

On the same day Buratai addressed the 8th Division, Nigerian Army spokesman Brigadier Sami Usman suggested the Boko Haram leadership was in a rapid state of decline: “There is no doubt that the main Boko Haram terrorists’ group factional leader, Abu Bakr Shekau, is in a terrible state of health and not much a threat as he is now a spent horse, waiting for his Waterloo. However, Abu Mus’ab al-Barnawi… will soon be captured” (Premium Times [Abuja], January 8, 2018).

Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari declared as early as December 2015 that Boko Haram had been “technically defeated.” The president used his 2018 New Year’s Day address to again declare Boko Haram “defeated,” though he acknowledged “isolated attacks still occur” (Premium Times [Abuja], January 1, 2018). On the same day, al-Barnawi’s faction of Boko Haram claimed to have killed nine Nigeria soldiers in an assault on the Kanama barracks in Borno State (Telegram Messaging via BBC Monitoring, January 1, 2018).

Lake Chad (WFP/Giulio D’Adamo)

Lake Chad (WFP/Giulio D’Adamo)

As if to mock the president, Abu Bakr Shekau appeared in a 31-minute Hausa language video the following day to report “We are in good health and nothing has happened to us.” Shekau went on to claim credit for a series of grisly attacks on villagers and loggers in northeastern Borno State (The Guardian [Lagos], January 2, 2018; Vanguard [Lagos], January 2, 2018). Another video released on January 15 showed Shekau firing weapons as well as school girls kidnapped from Chibok in 2014 and weeping female police officers who were abducted in June 2017 to be the insurgents’ “slaves” (Sahara Reporters, January 15, 2018).

The AIS report of July 29, 2017 noted that members of the al-Barnawi faction of Boko Haram were relocating from the Sambisi Forest to the Nigerian city of Kano (capital of Kano State in northwest Nigeria). This was confirmed by a January 6, 2018 Nigerian Army statement reporting that junior and senior al-Barnawi faction commanders were fleeing to Kano after the latest Nigerian government offensive (PR Nigeria, January 6, 2018). Shekau’s faction is still operating in the Sambisi Forest region but is under pressure from the Nigerian Army.

Nigeria’s federal government announced in December that it intended to withdraw $1 billion from the controversial Excess Crude Account (ECA, currently standing at $2.32 billion) to combat Boko Haram. Media and opposition parties questioned why such an enormous sum was needed to fight a movement that, according to government leaders, was already vanquished. Amidst opposition fears the funds would be used for political purposes, the government has since suggested the money will not be used solely against Boko Haram and would in any case not be released without the approval of the National Assembly (Vanguard [Lagos], December 30, 2017; January 18, 2018).

Operation Deep Punch II

Nigerian Troops in Operation Deep Punch II (Saynaija)

Nigerian Troops in Operation Deep Punch II (Saynaija)

Nigerian authorities claimed success in mid-December 2017 with coordinated ground-air attacks on Boko Haram hideouts in the Lake Chad islands as part of “Operation Deep Punch II,” [3] arresting 407 suspected militants and their family members (Premium Times [Abuja], December 16, 2017). Large stocks of food, fuel, ammunition, explosives and motorcycles were seized and destroyed, but not without resistance; Boko Haram suicide bombers struck an 8th Division MRAP (Mine Resistant Ambush Protected) armored personnel vehicle with a car filled with explosives, killing three soldiers and a member of the CJTF as well as wounding nine others (The Nigerian Voice, December 9, 2017; Nigerian Army official website, December 20, 2017). Saying the deployment of the 8th Division in Borno was a “major strategic decision,” General Buratai declared the unit had “lived up to expectations” (The Nation [Lagos], January 8, 2018).

One tactical innovation used by Operation Safe Haven is the deployment of counter-terrorist troops on motorcycles in remote areas (Vanguard [Lagos], December 1, 2017). Boko Haram has long used motorcycles to carry out terrorist attacks.

On a more technologically advanced level, Nigeria will soon take possession of 12 Embraer Super Tucano A-29 turboprop aircraft and munitions from Brazilian Embraer’s US partner, the Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC). The nearly $600 million sale was initially blocked by the Obama administration over human rights concerns but has since been approved by the Trump administration. The highly maneuverable counterinsurgency warplanes were designed in Brazil for work in the Amazon Basin and are specially adapted for conditions of high temperatures, humidity and precipitation, conditions more likely to be encountered in the restive Nigerian south rather than arid Borno province. Nonetheless, the aircraft will be useful, particularly if military ground-air coordination can be improved.

Conclusion

Boko Haram is still far from a spent force and remains a regional threat, with recent attacks on troops and civilians in Niger (seven soldiers killed on January 20), Cameroon (four civilians killed on January 11) and Nigeria’s Adamawa State (five civilians killed on January 19) (News24, January 20, 2018; AFP, January 11, 2018). The Nigerians have made significant progress in the Lake Chad region, though clearing the Sambisi Forest of Boko Haram militants has proved frustratingly elusive despite all the claims of victory.

The recent arrest of a suspected Boko Haram terrorist in Germany raises concerns that the successful elimination of Boko Haram as a regional threat might be the beginning of Boko Haram as an international phenomenon as surviving members disperse and take advantage of easy entry into Europe and North America. At the moment, the greatest impediment to Boko Haram’s out-migration from the region is the relative impoverishment of many of its members, though leading figures will certainly have the means and resources to escape Nigeria’s security forces and initiate new operations in Africa and possibly abroad.

Notes

- “General with a Deadline: Ibrahim Attahiru’s 40 Days to Seize Boko Haram Leader Abu Bakr Shekau Dead or Alive,” AIS Special Report, July 29, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3984

- See “Choosing a Figurehead over a Fanatic: A Profile of Abu Musab al-Barnawi, the New Leader of the Islamic State in West Africa,” Militant Leadership Monitor, August 31, 2016, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3712

- Deep Punch I was a mid-2017 operation to clear Boko Haram bases in the Sambisi Forest.