Andrew McGregor

July 14, 2017

The Middle East diplomatic crisis that has set a coalition of Arab states against Qatar has inevitably spilled over into Libya. A number of those states party to the dispute have been involved in a proxy war, with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt backing the eastern-based House of Representatives (HoR) and Khalifa Haftar’s anti-Islamist Libyan National Army (LNA), while Qatar and (to a lesser extent) Turkey support the Tripoli-based and UN-recognized Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (GNA).

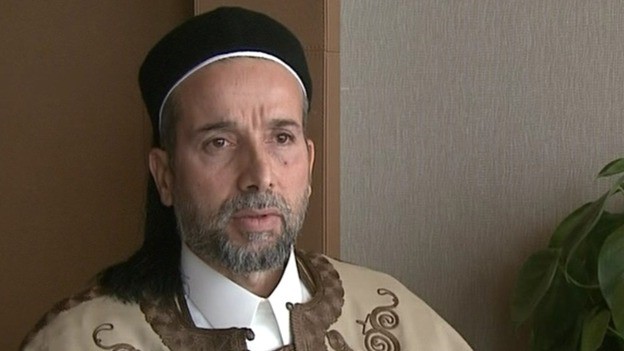

Al-Sadiq Abd al-Rahman Ali al-Ghariani

Al-Sadiq Abd al-Rahman Ali al-Ghariani

The main issues in the Gulf dispute are Qatar’s sponsorship of al-Jazeera and the channel’s willingness to criticize regional leaders (save Qatar’s al-Thani royal family), Qatar’s provision of a refuge for members of the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, its support for Islamist movements and its cooperative relations with Iran, with which it shares one of the world’s largest natural gas fields.

Amid the dispute Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the UAE produced a “terrorist list” of 59 Qatari or Qatari-allied individuals from nine Arab countries, including five individuals from Libya (The National [Abu Dhabi], June 9). [1] The list-makers seek to coerce Qatar to assist in Iran’s isolation and to end its support for the Muslim Brotherhood. This Arab states’ list was followed by a second list of 76 Libyan “terrorists” issued by the HoR’s Defense and National Security Committee on June 12, seven days after the HoR and its interim government severed relations with Qatar (Libya Herald, June 12).

What follows examines the most notable Libyans named on those lists, their contacts with Qatar and the reasons behind their inclusion.

Qatar’s Involvement in Libya

During Libya’s 2011 revolution, Qatar deployed its air force against then Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi’s loyalists and installations. It also provided substantial arms and supplies to revolutionary forces in Libya, earning it a significant degree of good will within the country.

Since then, however, Qatar has focused its support on Islamist forces operating in Libya, a policy that has aggrieved nations such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, all of which seek to stifle the growth of Islamist movements that could challenge the legitimacy of their regimes. Qatar’s continued insistence on playing a role in Libya’s domestic politics since then has also brought on resentment and even anger in many quarters of Libyan society. Both Egypt and the UAE, meanwhile, mount regular air operations against Islamist targets inside Libya. [2]

On June 8, LNA spokesman Colonel Ahmad al-Mismari presented audio, video and documentary evidence of massive political and military interference by Qatar in Libya since the 2011 revolution, comprising a wave of assassinations (including an attempt on Haftar’s life), recruitment and transport of Libyan jihadists to Syria, funding of extremist groups and training in bombing techniques via Hamas operatives from the Khan Yunis Brigade. Much of this activity was allegedly orchestrated by Muhammad Hamad al-Hajri, chargé d’affaires at the Qatari embassy in Libya, and intelligence official General Salim Ali al-Jarboui, the military attaché (al-Arabiya, June 9; The National [Abu Dhabi], June 8).

Mismari also claimed on June 22 to have records of “secret meetings” held by the Sudan Armed Forces and attended by Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir that confirmed a conspiracy to support terrorism in Libya, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, and alleged that Qatar and Iran were operating arms factories in Sudan to supply Libyan terrorists (Libya Herald, June 22).

On June 29, al-Mismari declared that the LNA was fighting “not with Libyan terrorists, but with transnational terrorism” supported by “the triad of terrorism in Libya,” Qatar, Sudan and Turkey. The colonel also claimed that the LNA’s intelligence department had obtained recordings of an al-Jazeera correspondent coordinating covert flights by Qatari aircraft to Libya to “support terrorist groups” (al-Arabiya, June 29).

Egypt also views Libya as a battleground for its efforts to eliminate the Muslim Brotherhood. On June 28, Egypt’s foreign ministry claimed Qatar was supporting terrorist groups in Libya operating under the leadership of the Brotherhood, resulting in terrorist attacks in Egypt (Asharq al-Awsat, June 29; al-Arabiya, June 28)

Qatar provides a home and refuge for members of the Muslim Brotherhood, but it does so on the condition that they do not involve themselves in Qatari politics. The local chapter of the Brotherhood shut itself down in 1999 after expressing approval of the emirate’s political and social direction (The National [Abu Dhabi], May 18, 2012).

The Muslim Brotherhood’s political misadventures in Egypt led to distrust of the Brothers’ agenda in Libya, especially as the movement still struggles to establish grass-roots support after decades of existence in the Gaddafi era as a movement for Libyan professionals living in European exile.

List One: The Arab States’ List

The “terrorist” list issued by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the UAE included the following Libyan individuals:

Ali Muhammad al-Salabi – Al-Salabi, a second-generation Muslim Brother, was sentenced to eight years in prison at 18-years-of-age for his alleged connection to a plot to kill Gaddafi.

The intellectual and spiritual leader of the Libyan Brotherhood, al-Salabi consistently presents himself as a proponent of democracy and cooperation with international efforts to combat terrorism (Libya Herald, March 1, 2016). Al-Salabi developed ties with Qatar in 2009, when Qatar funded an al-Salabi headed de-radicalization initiative for imprisoned members of the al-Qaeda associated Jamaa al-Islamiya al-Muqatila bi-Libya (Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, or LIFG). When the 2011 revolution erupted, al-Salabi returned to Libya to act as a local conduit for Qatari arms, intelligence and military training. He now holds Qatari citizenship and has a close relationship to Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the Muslim Brotherhood’s 91-year-old Qatar-based spiritual leader (also named on the list) (Libya Herald, October 5, 2015). Al-Salabi has close ties with Abd al-Hakim Belhaj (see below), with whom he founded the Islamist Hizb al-Watan (Homeland Party) in 2011.

Abd al-Hakim Belhaj– An allegedly reformed militant, Belhaj is chairman of Hizb al-Watan, believed to be financed by Qatar. Belhaj was amir of the LIFG and the leader of the post-revolutionary Tripoli Military Council. He is believed to have received substantial support from Qatar during the 2011 revolution and routinely defends Qatari activities in Libya against their critics.

Mahdi al-Harati – A Libyan-born Irish citizen with military experience in Kosovo and Iraq, al-Harati returned from Ireland during the 2011 revolution and took command of the Tripoli Brigade. Briefly mayor of Tripoli before being ousted in 2015, al-Harati later led Libyan and Syrian fighters in Syria as part of the anti-government Liwa al-Ummah, a unit alleged to have included London Bridge attacker Rachid Redouane, a resident of Ireland (al-Arabiya, June 9; Libya Herald, June 9; Telegraph, June 6). The LNA alleges al-Harati is supported by Qatari intelligence (al-Arabiya, June 9).

Ismail Muhammad al-Salabi – Brother of Ali Muhammad al-Salabi, Ismail was imprisoned by Gaddafi in 1997 and released in 2004. He became a principal recipient of Qatari arms shipments during the revolution as commander of the Raffalah Sahati militia, part of a coalition of Islamist militias known as the February 17 Brigade (al-Hayat, May 19, 2014). Clashes with Hatar’s LNA began in 2014 and continue to this day, with Ismail serving a prominent member of the Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB) coalition. He is reputed to have a close relationship with Qatari intelligence chief Ghanim bin Khalifa al-Kubaisi (al-Arabiya, June 9).

Al-Sadiq Abd al-Rahman Ali al-Gharaini – The 75-year-old al-Ghariani was, until recently, the controversial Grand Mufti of Libya and the head of the Dar al-Ifta, the office responsible for issuing fatwa-s (religious rulings). The Mufti considers Haftar and those under him to be “infidels” and has called for the destruction of the HoR, which voted to sack him in November 2014. The Dar al-Ifta office in Tripoli was shut down by the GNA on June 1, 2017, and all its contents were confiscated (al-Arabiya, June 1). A strong supporter of Qatar’s involvement in Libya who commands the allegiance of several Islamist militias, the Mufti is perceived by some Libyans as a supporter of religious extremism. Nonetheless, the League of Libyan Ulama (religious scholars) issued a strong condemnation of the Mufti’s inclusion in the terrorist list, warning against “accusing the righteous” (Libya Herald, May 10).

Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB) – The BDB was one of 12 organizations to appear on the “terrorist” list. A coalition of soldiers, Islamists and revolutionaries, the BDB has pledged allegiance to Mufti al-Ghariani. The BDB offered to demobilize and disband on June 23 following an intense backlash after their brutal attack on the Brak al-Shatti airbase on May 18 and their subsequent failure to hold Jufra against an LNA offensive. [3] The coalition claimed it had been disparaged as a terrorist group only after it exposed a plot by France, Turkey and the UAE to invade Libya (Libya Herald, June 23; Libya Observer, June 23). On June 6, Misratan officials ordered the BDB (which it called “the Mufti’s forces”) to disband and surrender their weapons, threatening force if their demand was not complied with (Libya Herald, June 6). Instead, the group relocated to Sabratha, where it remained under arms. By July 10, the still-undissolved BDB was reported to be leading an offensive by pro-Khalifa Ghwell forces against pro-GNA militias in Garabulli, east of Tripoli (Libya Herald, July 10; Libya Express, July 9). [4]

The BDB, noting the UAE’s active military role in the Libyan conflict and its support for the “war criminal” Haftar, described the list as a fabrication designed with the intent of imposing “political restrictions on anyone who poses a threat to the UAE’s attempt at supremacy over the entire region” (Libya Observer, June 10).

List Two: The HoR’s List

The majority of those on the HoR list are based in Tripolitania. Most of those listed share an opposition to Haftar, the LNA and/or the HoR, though the role of many is inflated. Many are described as members of the “Muqatila,” a shorthand reference to the now defunct LIFG. The inference is that they are former members or remain sympathetic to the goals of the group, which was once closely associated with al-Qaeda.

While there is no apparent order to the HoR list, it makes more sense when those on it are gathered into focused groups, along with more detailed (and occasionally corrected) descriptions. There is, however, often some overlap in these unofficial categories.

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB)

Twenty-nine members of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood made the list. The MB described the inclusion of its members on a “terrorist list” as “defamation” (Libya Herald, June 11). Many are resident in Doha, the Qatari capital, and receive Qatari funding. The most prominent of those included are:

Muhammad Sawan – Chairman of the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Hizb al-Adala wal-Tamiyya (Justice & Construction Party, or JCP), since its founding in 2012. He is a Misratan who was imprisoned during the Gaddafi era.

Ahmad al-Suqi – The head of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood, elected in October 2015.

Nizar Kawan – An Amazigh (Berber) member of the Libyan State Council and an official in the JCP. [5] Kawan was the victim of a failed assassination attempt and RPG attack on his home in June 2014. The attack was allegedly instigated by the pro-Haftar Libyan ambassador to the UAE, Aref al-Nayed, who was recorded urging a similar attempt on the life of Khalid al-Sharif (see below) (Libya Observer, September 3, 2015).

Fawzi Bukatif – A Misratan, Bukatif is the current Libyan ambassador to Uganda. A reputed financial coordinator for the MB with Qatar, he was the commander of the February 17 Brigade during the revolution and has close ties to Ismail al-Salabi. Bukatif accused the HoR of inciting violence with the list and threatened legal action: “I’m not against Hafter or the HoR, but I don’t agree with what they are doing. It seems they want to fight and kill anyone who disagrees with them” (Libya Herald, June 12).

Dar al-Ifta and Associates of Sadiq al-Ghariani

The most prominent of these are:

Abd al-Basit Ghwaila (Daily Mail)

Abd al-Basit Ghwaila (Daily Mail)

Abd al-Basit Ghwaila – Director of the Tripoli office of the Ministry of Awqaf (religious endowments), Ghwaila is a Libyan-born Canadian citizen. He became the focus of attention when it was revealed that he was a close friend of the father of Manchester bomber Salman Abedi as well as the founder of an Islamic youth group to which Salman belonged. In 2016, his own son Awais was killed fighting alongside extremists in Benghazi. Ghwaila is an important official in al-Ghariani’s Tanasuh Foundation and a regular preacher on the Mufti’s Tanasuh TV station (Libya Herald, June 6).

Salem Jaber – A leader in the now dissolved Dar al-Ifta, Shaykh Salem advocates jihad and is a Salafist proponent of Saudi-style Islamic education. He demands beards for men and has called for drinkers and fornicators to be whipped. The list suggests he is a spiritual leader in the BDB.

Hamza Abu Faris – A leading Libyan religious scholar and former Islamic affairs minister, he is described on the list as an associate of the BDB and “instigator of jihad.”

The Manchester/Birmingham Connection

Tahir Nasuf – A Manchester-based LIFG fundraiser and former director of the group’s main fundraising organization, the now banned UK-based al-Sanabel Relief Agency. Funds flowed from Sanabel to Abu Anas al-Libi in Afghanistan, wanted for alleged involvement in the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar al-Salaam (The Guardian, May 28). Nasuf was on the UN sanctions list from 2006 to 2011.

Khalid Tawfik Nasrat – A former LIFG leader and the father of Zuhair Nasrat, one of the detainees in the investigations of the Manchester attack. Zuhair was arrested at the south Manchester Nasrat family home where Manchester bomber Salman Abedi frequently stayed. Nasrat and his two eldest sons returned to Libya to fight in the 2011 revolution (Daily Mail, May 29).

Abd al-Basit Azzouz – After fighting in Afghanistan, LIFG member Azzouz arrived in Manchester in 1994, where he settled alongside other LIFG members. In 2006, he was arrested by British police for alleged ties to al-Qaeda and detained for over nine months before being released on bail. Azzouz left for Pakistan and was appointed head of Libyan al-Qaeda operations by al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawihiri in May 2011. An expert bomb-maker, Azzouz had some 200 recruits under his command in Libya. Suspected of involvement in the 2012 attack on the American consulate in Benghazi, he was named in 2014 by the U.S. State Department as one of ten “specially designated global terrorists” (Telegraph, September 27, 2014; Express [London], May 24). He was arrested in Turkey in 2014 in a joint Turkish/CIA operation and sent to Jordan before his expected deportation to the United States to face charges. His public trail goes cold after that (Hurriyet [Istanbul], December 4, 2014). In February 2016, the UN added him to its al-Qaeda sanctions list, implying he was again at large. [6]

Bashir Muhammad al-Faqih – He is described in the list as “the spiritual leader of al-Qaeda and the LIFG in Libya.” As a resident of Birmingham and former member of the LIFG, al-Faqih was convicted and sentenced to four years in prison in 2007 after admitting to charges under the UK’s Terrorism Act. In 2014, his appeal to the European Court of Justice resulted in an EU order to overturn his conviction and return his passport (BBC, July 17, 2007; Manchester Evening News, October 8, 2010). He was involved in al-Qaeda financing via the Sanabel Relief Agency, which put him on the UN sanctions list from 2006 to 2011.

Politicians

The most prominent of these are:

Abd al-Rahman al-Shaibani al-Suwehli

Abd al-Rahman al-Shaibani al-Suwehli

Abd al-Rahman al-Shaibani al-Suwehli – As chairman of the Libyan State Council since April 6, 2016, Suwehli has challenged the legitimacy of the HoR. A bulletin from the State Council said that the HoR was using the term “terrorism” to vilify and denigrate their opponents through the list and threatened legal action (Libya Herald, June 12). Suwehli and Presidency Council chief Fayez Serraj were targeted for assassination when their motorcade came under heavy fire on February 20. Suwehli later accused GNS head Khalifa Ghwell of being behind the attack (Libya Herald, February 20).

Omar al-Hassi – After the formation of the elected HoR in 2014, the Islamist al-Hassi became “prime minister” of an alternative parliament formed from GNC members who had failed to be re-elected. He was dismissed in 2015 after unspecified accusations by an auditor. The list provides the unlikely description “field commander and political official in BDB.”

Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB)

The most prominent commanders on the list are:

Brigadier General Mustafa al-Sharkasi – A professional soldier and former air force colonel in the Gaddafi-era, al-Sharkasi has emerged as the dominant commander in the BDB. Turning against the regime, he acted as a militia commander in Misrata during the revolution. Once part of Haftar’s LNA, he is now bitterly opposed to him (Libya Herald, November 13, 2016).

Al-Saadi al-Nawfali – The leader of the Operations Room for the Liberation of the Cities of Ajdabiya and Support for the Revolutionaries of Benghazi. This group cooperates closely with the BDB, in which he also holds a leadership position. Al-Nawfali has been variously described as an al-Qaeda operative, a former Ansar al-Sharia commander in Ajdabiya and a supporter of Islamic State (IS) forces.

Anwar Sawan – A Misratan supporter of the BDB and the Benghazi Shura Council, Sawan is a major arms dealer to Misratan Islamist militias. He supported the fight against IS in Sirte and opposes both Haftar and Serraj.

Ziyad Belam – A commander in the BDB and former leader of Benghazi’s Omar al-Mukhtar Brigade and the Benghazi Revolutionaries Shura Council (BRSC), an alliance of Benghazi-based Islamist militias that once included local IS fighters. He was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt in October 2014.

The BDB responded to the HoR’s “terrorist” list by providing their own “top 11” terrorist list focused on eastern-based civilian supporters of Haftar and the HoR. The most prominent individuals on the list were HoR President Ageela al-Salah and HoR Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thinni. (Libya Herald, June 16).

Islamic State (IS)

Ali al-Safrani and Abd al-Hadi Zarqun (a.k.a. Abd al-Hadi al-Warfali) – Both were accused of being financiers for IS in Libya. Sanctions were imposed on the two by the U.S. Treasury Department in April.

Mahmoud al-Barasi – A former Ansar al-Sharia commander in Benghazi, now purported by the list to be an IS amir in that city. He once said Ansar’s fight was against “democracy, secularism and the French,” and labeled government members “apostates” who could be killed (Libya Herald, November 25, 2013).

Al-Qaeda Operatives

The most notable of these are:

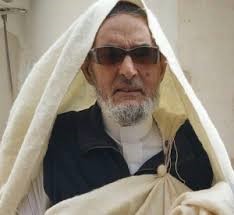

Muhammad al-Darsi (al-Jazeera)

Muhammad al-Darsi (al-Jazeera)

Muhammad al-Darsi – A leading al-Qaeda figure in Libya, Darsi was given a life sentence in Jordan in 2007 for planning to blow up that nation’s main airport. He was released in 2014 in exchange for the kidnapped Jordanian ambassador to Libya, who was seized by gunmen in Tripoli (al-Jazeera, May 14, 2014).

Abd al-Moneim al-Hasnawi – Allegedly a high-ranking member of Katibat al-Muhajirin in Syria, Abd al-Moneim was recently spotted back in Sabah (Fezzan), where he was allegedly working with the Misratan Third Brigade, the BDB and the remnants of Ibrahim Jadhran’s Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG) (Menastream.com, November 15, 2016). The list describes him as a representative for al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in southern Libya.

Militia Commanders

Salah Badi – A Misratan, Badi was an officer in Gaddafi’s army but was later imprisoned. A former GNC parliamentarian, he resigned in 2014. Badi formed the Jabhat al-Samud (Steadfastness Front) in Tripoli in June 2015. Badi supports Khalifa Ghwell’s GNS and opposes both the GNA and Haftar. He was recently seen leading the Samud Front in a pro-GNS offensive against Tripoli in early July (Libya Herald, July 7).

Tariq Durman – Leads the Ihsan Brigade in Tripoli, which is made up of supporters of Mufti al-Ghariani. He supports the GNS.

Khalid al-Sharif – A deputy amir in the LIFG, Khalid was captured in 2003 and held prisoner in a secret CIA detention center in Afghanistan for two years. He was then returned to Libya and imprisonment under Gaddafi (Christian Science Monitor, May 7, 2015). Khalid controlled Tripoli’s Hadba prison until May 26, when it was seized by Haitham Tajouri’s Tripoli Revolutionaries’ Brigade, which then destroyed al-Sharif’s home (Libya Herald, May 27). A search revealed the prison to have contained a bomb-making factory (Libya Herald, June 4). In June, the Libyan National Committee for Human Rights tied Manchester bomber Salman Abedi to Khalid al-Sharif and other former LIFG members and demanded the International Criminal Court and the UN investigate “Qatar’s role as a financier of this group” (Arab News, June 3).

Sami al-Sa’adi – Al-Saadi left Libya for Afghanistan in 1988, where he became a deputy amir of the LIFG. He was arrested in a joint UK/US operation in 2004 and returned to Libya, where he was tortured and spent six years in prison. The UK paid £2.2 million in compensation in 2012 but did not accept responsibility for the rendition. After the revolution, he became close to Mufti al-Ghariani, founded the Umma al-Wasat Party and was a commander in the Islamist Libya Dawn coalition. In late May, Saadi’s Tripoli home was destroyed by the Tripoli Revolutionaries’ Brigade (Libya Herald, May 27).

Ahmad Abd al-Jalil al-Hasnawi – A Libyan Shield southern district commander, the LNA claimed al-Hasnawi planned and led the BDB’s Brak al-Shatti attack (Libya Herald, May 19; Channel TV [Amman], May 22, via BBC Monitoring). A GNA loyalist, al-Hasnawi commands wide support within his Fezzani Hasawna tribe.

Outlook

The Libyan component of these two “terrorist” lists have a common purpose — to lessen foreign resistance to the takeover of Libya by the HoR-backed LNA while simultaneously discrediting the counter-efforts of Qatar.

Egypt’s military regime in particular is determined to eliminate Muslim Brotherhood influence in the region. Another common theme of the lists is the insistence that the arms embargo on Libya be lifted in order to supply Haftar with the weapons needed to defeat “terrorism” and control the flow of “foreign fighters” (despite their being used by both Haftar’s LNA and pro-GNA forces).

Clearly designed for an international audience, the HoR’s list is light on IS militants (already despised by the West) and heavy on political, military and religious opponents to Haftar and his Egyptian and UAE backers. The BDB, as one of the strongest military challengers to Haftar’s LNA, is particularly singled out.

While some of the individuals mentioned above have long histories of supporting terrorist activity, many of the lists’ lesser individuals not included here can only be regarded as having the most tenuous of links, if any, to terrorism.

In this sense, the list may be viewed as political preparation for an expected Haftar assault on Tripoli later this year, branding all possible opposition in advance as “terrorists” for international consumption.

Notes

- A Qatari official insisted that at least six of the individuals on the list were already dead (Foreign Policy, June 15).

- The UAE uses al-Khadim airbase in Marj province for operations by AT-802 light attack aircraft and surveillance drones (Jane’s 360, October 28, 2016). The UAE also controls an estimated 70% of Libyan media, according to an Emirati investigative website (Libya Observer, June 13).

- See “Libya’s Military Wild Card: The Benghazi Defense Brigades and the Massacre at Brak al-Shatti,” Terrorism Monitor 15(11), June 2, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/libyas-military-wild-card-benghazi-defense-brigades-massacre-brak-al-shatti/

- Khalifa Ghwell is leader of a third rival government, the Government of National Salvation, which has some support from Mufti al-Ghariani. The offensive is the latest in a series of attempts by Ghwell to overthrow the GNA administration in Tripoli.

- The State Council was formed by the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement as an advisory body to the GNA/Presidency Council and HoR as a third element of the unified government.

- https://www.un.org/sc/suborg/en/sanctions/1267/aq_sanctions_list/summaries/individual/abd-al-baset-azzouz

This article first appeared in the July 14, 2017 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor