Andrew McGregor

Eurasia Daily Monitor, 22(129), Washington DC

September 30, 2025

Executive Summary:

- The presence of Russian military personnel in Mali has failed to prevent the expansion of the jihadist insurgency into the once-safe central and western regions of the country.

- Fissures have erupted in Mali’s ruling military junta over issues related to operational cooperation with Russian military personnel who tend to operate independently of Mali’s command structure and are accused of human-rights abuses.

- Russian forces are unhappy with difficulties related to their entry into Mali’s lucrative minerals sector and the arrival of Turkish military contractors assigned to train the president’s security staff.

Four years into the Russian military deployment that began with the arrival of Wagner personnel, Mali has become less secure and the jihadists have grown stronger, more numerous, wider ranging, and more daring attacks on urban centers and military bases (see EDM, September 6, 2023, March 12, 2024; see Terrorism Monitor, June 26, 2020, December 11, 2024). Three months after Wagner withdrew in June and Russia’s Africa Corps began its Malian deployment, the Russian military presence is not only failing to quell Mali’s 13-year-old Islamist and separatist insurgency, but is now adding to Mali’s political turmoil (see EDM, July 9). Russian forces have both failed to retake the jihadist homeland in northern Mali and to prevent a large-scale infiltration of Islamist gunmen into the once-safe central and western regions of the country. The inability of foreign forces, such as the recently expelled French military, to repress the insurgency is beginning to create fissures in Mali’s five-year-old military junta.

JNIM celebrate after the ambush of a Russian convoy near Ténenkou, August 1, 2025

JNIM celebrate after the ambush of a Russian convoy near Ténenkou, August 1, 2025

Recently, the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin (JNIM) movement scored a victory over Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMa) and the allied Russian Africa Corps when it ambushed a Russian convoy near Ténenkou in the central Malian region of Mopti on August 1. An estimated 14 Russians and over 35 Malian soldiers died (France24, August 13). The bodies of three white combatants were shown in the video, including one wounded soldier who was executed with a shot to the head. A second video showed JNIM fighters rummaging through a damaged Russian Ural-4320 truck (X/@Permafr95699535, August 1). The scene was reminiscent of the Wagner/FAMa defeat at Tinzawatène at the hands of JNIM and Tuareg separatists of the Cadre stratégique pour la défense du peuple de l’Azawad (CSP-DPA) on July 25, 2024 (see EDM, September 11, 2024).

JNIM fighters inspect damaged Russian truck at Ténenkou

JNIM fighters inspect damaged Russian truck at Ténenkou

The region around Ténenkou is dominated by the Fulani, cattle-herding Muslims whose regular clashes with farming communities have led to reprisals by government forces and local militias. This leads to recruitment by Fulani-dominated jihadist groups such as the al-Qaeda-aligned Katiba Macina (MLF) (CTC, February 2017). Fulani fighters from the Katiba Macina were at the forefront of a September 17, 2024, raid on Russian and Malian military personnel in Mali’s capital, Bamako (see EDM, October 9, 2024). MLF leader Amadou Koufa stated that the raid was a response to civilian massacres by FAMa and their Russian allies (X/SaladinAlDronni, September 17, 2024).

The Russian military presence has failed to prevent the expansion of jihadist operations into parts of Mali that were previously unaffected by such. JNIM’s June to September offensive in western Mali climaxed with the September 3 announcement of a JNIM blockade of imports from neighboring Senegal and Mauritania (Africa Report, September 7). The blockade of the Kayes and Nioro regions is intended to prevent the import of fuel and other goods to landlocked Mali and Bamako, where fuel is already in short supply, affecting both military and commercial flights (Anadolu Ajansı, July 10). Mali’s regime responded with airstrikes in Kayes on September 8 after jihadists stopped and emptied fuel tankers from Senegal (TRT Global, September 8).

The regime’s inability to restore security to Mali, even with the aid of Russian troops, has created an atmosphere of distrust in the highest levels of the military. An unauthorized early August meeting of senior officers to discuss issues related to cooperation with the Russian Africa Corps led to a wave of arrests of front-line officers and other ranks that began on August 10 and continued for days. At least 55 soldiers were arrested, including two popular generals, on charges they were preparing a coup against the junta with the help of “foreign states” (Africa News, August 11; Al-Jazeera, August 15; L’Essor, August 19).

General Sadio Camara meets with Russian defense officials in Moscow, including Yunus-Bek Yevkurov (left) (Russian Defense Ministry)

One junta leader who escaped arrest was Minister of Defense and Veterans Affairs Lieutenant General Sadio Camara, the individual responsible for arranging the arrival of Russian contractors in Mali. Camara has acted as the point man for the junta’s dealings with both the Wagner Group and its successor, the Africa Corps, which operates under the direction of Russia’s Ministry of Defense. Camara, however, has come under suspicion after the mass arrests of suspect officers, most of whom belong to Mali’s Garde Nationale, known as the “Brown Berets” (RFI, August 10). The Garde and its leaders are closely tied to Camara, who founded the force. Disagreements between junta leader General Assimi Goïta and Camara over the allocation of Malian mines to Russian interests may have contributed to the growing rivalry between the two men (The Sentry, August 2025). Camara is seeing much of his network of supporters dismantled, leaving him in a precarious position regarding his former ally, Goïta. While Goïta still approves of the Russian presence and has even authorized its expansion through recent talks in Moscow, he is wary of allowing a transfer of resources and national authority to the Russians, as has occurred in the Central African Republic.

Mali’s Garde Nationale – The “Brown Berets” (Bamada.net)

Mali’s Garde Nationale – The “Brown Berets” (Bamada.net)

Only days after the purge of many of his followers, Camara represented Mali in Moscow during a meeting of defense ministers of the Alliance des États du Sahel (AES – Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso) and their Russian counterpart, Andrei Belousov, as well as Africa Corps leader Yunus Bek Yevkurov (see MLM, April 18, 2024; The Moscow Times, August 14; Bamada.net, August 15). During the proceedings, Camara declared his support for Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine (APA, August 14). In Mali, Camara has the support of Modibo Koné, the powerful pro-Russian leader of the Agence Nationale de Sécurité de l’État (ANSE) and a product of Camara’s Garde Nationale (Bamada.net, March 24).

SADAT mercenaries with President Erdoğan of Turkiye (North Africa Post)

Complicating the Russian relationship with the regime is the arrival in Bamako of SADAT, a self-proclaimed Turkish private military company providing “military training and defense consulting” (Sadat.com.tr, accessed September 28). SADAT’s main role in Mali appears to be the provision of training to Goïta’s security detail, though there are reports of Syrian SADAT members finding themselves on the front lines of the war against the Islamists (Le Monde, June 7, 2024). SADAT relies heavily on recruitment from Syrian fighters of the Syrian National Army (SNA, a coalition of Turkish-aligned Syrian rebels) and Turkmen from Syria’s Sultan Murad Division (NATO Defense Foundation, April 9). The organization was founded in 2012 by Erdoğan’s former military advisor, Brigadier General Adnan Tanrıverdi, and is believed to still enjoy Erdoğan’s patronage (Medya News, June 25, 2023; Le Monde, June 7, 2024; Gazete Duvar, December 27, 2024). Türkiye’s main opposition leader, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (leader of the Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi – CHP), stated in June that “Russia’s Wagner is Türkiye’s SADAT Inc” (Duvar, June 24). SADAT’s role in protecting the junta leader suggests Goïta has some degree of suspicion regarding the ultimate intentions of the Russians or their supporters in Mali.

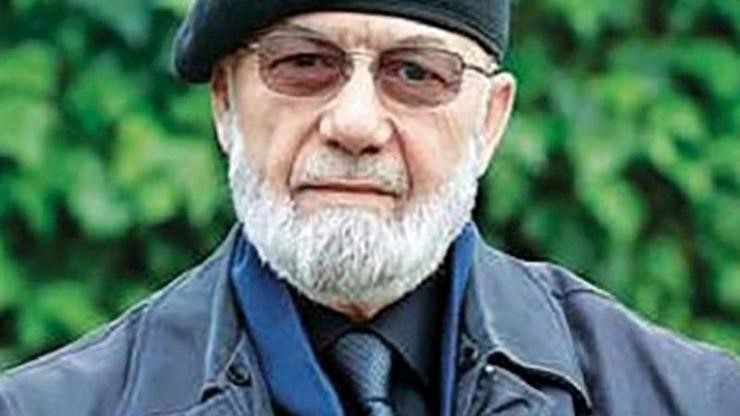

SADAT founder Adnan Tanriverdi (CNN Türk)

SADAT founder Adnan Tanriverdi (CNN Türk)

The junta appears to have been under the impression that Russian forces might enable it to escape the neo-colonialism inherent in the French and UN military presence in Mali. Instead, they have found a new partner set on accessing Mali’s natural resources, and that is even more selective in choosing which operations or actions it should carry out than the French.

The Russians so far appear to be disappointed by the lack of access to Mali’s lucrative mining sector, with the expected lucrative mining licenses failing to materialize for the most part (The Sentry, August 2025). One-half of Mali’s tax revenues derive from its gold mining industry (Reuters, July 19, 2023). Russia looks toward gold revenues from its activities in Africa to help fund its ongoing and costly war against Ukraine (see EDM, July 16).

The replacement of Wagner with the Africa Corps has not meant a wholesale replacement of Russian troops. Some 80 percent of Mali’s Africa Corps consists of Wagner personnel who chose to transfer into the new Russian Ministry of Defense unit rather than return to Russia, where they would likely find themselves on the front lines of the war against Ukraine (Africa Business Insider, August 28). There is growing friction between FAMa and the Russian troops, who tend to operate outside the Malian chain of command, appropriating resources, weapons, and transport for their operations. The Russian contractors are disliked for selectively intervening in support of FAMa.

As Mali endures economic, political, and military crises, the country’s ruling junta is seeking scapegoats. As ruptures appear in the ruling junta, it may only be a matter of time before the largely unproductive experiment with Russian security assistance offers Mali’s inept military rulers a new target for blame.