Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report

September 25, 2020

Agents of Egypt’s National Security Agency (NSA) working with Cairo police arrested acting general guide of the Muslim Brotherhood Mahmud Ezzat on August 28, 2020. The arrest was carried out during a raid on an apartment in New Cairo’s Fifth Settlement, southeast of the capital. Encrypted computers and telephones were seized, as well as documents alleged to relate to sabotage plans (Egypt Independent, August 28, 2020). Ezzat has been a fugitive for seven years; while he and his supporters spread rumors he was hiding in a foreign country to throw off his pursuers, Ezzat appears to have remained in Egypt the whole time, as is required for the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) according to the movement’s by-laws. It is also possible that Ezzat had difficulty escaping through Egypt’s tightened border controls. The regime of President ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi regards the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization and is determined to eliminate its influence and presence in Egypt. In the meantime, the groups suffers from organizational upheaval and internal divisions.

The Brothers (Ikhwan) are struggling to maintain a foothold in Egypt’s political process four years after its members were slaughtered in the streets of Cairo by security forces following the 2013 overthrow of Egyptian president and Brotherhood member Muhammad al-Mursi by General ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi and the Egyptian military. With most of the movement’s leadership serving long prison sentences or awaiting execution, the work of keeping the Brotherhood alive fell into the hands of fugitive leaders such as Mahmud Ezzat.

At the time of his arrest, Egypt’s Interior Ministry accused Ezzat of overseeing the car bomb assassination of Public Prosecutor Hisham Barakat (2015), the assassination at his home of Brigadier General Wael Tahoun (2015), the attempted assassination by car bomb of Assistant Public Prosecutor Zakaria ‘Abd al-Aziz (2016) and the car bombing outside the National Cancer Institute that killed 20 people and injured 47 (2019) (Egypt Independent, August 28, 2020).

With Ezzat’s arrest, only two members of the Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau remain at large. Of these, Ibrahim Munir became the Brotherhood’s new Acting General Guide, while Mahmud Hussein remains the movement’s secretary-general. Both, however, are currently in Turkey and unable to exert much influence within Egypt, especially among the movement’s younger members, most of whom have a strong dislike for the new Acting General Guide (Al-Ahram Weekly [Cairo], September 7, 2020). A number of imprisoned young members of the Brotherhood have now made a break from the movement’s Old Guard, issuing important ideological revisions designed to create conditions conducive to a reconciliation with the al-Sisi regime, which has succeeded in consolidating its control over most of the country. Munir has roundly denounced the revisions and remains unapologetic for any actions of the Old Guard that may have contributed to the existential crisis faced by the movement today.

Ezzat was wanted by Egyptian authorities in connection with the death of anti-MB protesters outside the movement’s headquarters in the Muquttam district of Cairo on June 30, 2013 (Al-Monitor, August 21, 2013). His current location is unknown, though speculation has placed him in Gaza, Turkey or even inside Egypt.

Ezzat was among five Egyptians added in November 2017 to the terrorist list of the Arab Quartet (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates) (Egypt Today, November 26, 2017). Known as a “hardliner,” Ezzat’s long membership at senior levels of the MB has given him an insider’s knowledge of the movement’s organization and finances, much of which is directed by him. Narrow, sharp features and a reputation for organizational skills have led Ezzat to be known as “the Brotherhood Fox” (Al-Monitor, August 21, 2013).

In various trials carried out since 2013, Ezzat has already received, in absentia, two life sentences and two death sentences on other charges. Ezzat will face retrial in these cases, as well as a case of alleged espionage to begin in December.

Ezzat’s arrest came only days after the death in prison of leading Muslim Brother Essam al-Erian, former secretary-general of the Brotherhood’s political wing, the Freedom and Justice Party, at the age of 66. Al-Erian was reported to have died from a heart attack in the maximum-security wing of Liman al-Turra Prison south of Cairo. The Islamist complained a number of times of “medical negligence” during his stay in al-Turra, including a refusal to treat the Hepatitis C he contracted while in detention (al-Jazeera, August 13, 2020).

Perhaps in light of this, as well as Muhammad al-Mursi’s death in al-Turra Prison in 2019, allegedly as a result of lack of medical care, the Brotherhood’s general office declared that the Egyptian military bore responsibility for Ezzat’s life, warning that he suffered from chronic illnesses and that illegal detention and torture would represent an “attempt at murder” (Middle East Monitor, August 29, 2020).

Background

Formed in Isma’iliya by Hassan al-Banna in 1928, the MB is a religious organization intended to advance political Islamism through social work and political agitation. Much disrupted by events since the 2013 coup, the MB’s leadership structure includes a majlis al-shura (consultative council) below a powerful 15-member Guidance Bureau (maktab al-irshad) with a Supreme Guide (murshid al-‘amm) and his deputies at its head.

The movement has had a difficult relationship with the state since a young MB member tried to assassinate the Egyptian prime minister in 1948. Thousands were jailed and al-Banna himself assassinated by unknown assailants shortly afterward. The movement was banned by President Gamal ‘Abd al-Nasser in 1954. When another Brother tried to kill Nasser in October 1954, a massive crackdown followed that put thousands of Ikhwan behind bars, including revolutionary ideologue Sayyid Qutb, whose works deeply influenced the young Ezzat.

Imprisonment

Ezzzat was arrested in 1965 and imprisoned alongside Sayyid Qutb and Dr. Muhammed Badi’e, who later became the movement’s Supreme Guide (2010 to present – Ezzat and now Munir are only Acting Supreme Guides during 77-year-old Badi’e’s incarceration). Qutb had already endured torture during nine years in prison; his re-arrest would lead to his execution the next year on charges of conspiring to assassinate the president and overthrow the government. Qutb believed that an Islamic administration could only be imposed by a vanguard of believers (tali’a mu’mina) who would lead the masses to Islam through revolutionary activity.

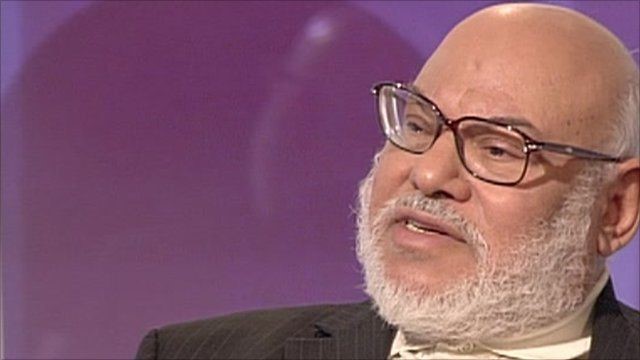

Dr. Muhammad Badi’e (Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters)

Dr. Muhammad Badi’e (Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters)

Ezzat became a pupil of fellow prisoner Shukri Mustafa, who took Qutbism to extremes after his release in 1971 with the formation of Jama’at al-Muslimin, better known as Takfir wa’l-Hijra (Excommunication and Flight) (Al-Monitor, August 21, 2013). Mustafa was also an adherent of the works of extremist icon Shaykh ibn Taymiya (1263-1328), but rejected most other Islamic scholarship, pulling his followers out of Egyptian society to live in caves (after the Prophet’s model, the concept of withdrawal from non-Islamic communities is known as hijra). Mustafa’s jihad ended with his capture and execution in 1978.

Qutbist ideology was influential among the movement’s leaders serving long prison terms, a group that included Ezzat and Badi’e. Nonetheless, the efficiency of President Hosni Mubarak’s security machine forced Ezzat and other Qutbists to acknowledge the temporary futility of a direct challenge to the state, and the movement shifted back to emphasizing religious education and social assistance as the means of expanding the MB’s influence. Ezzat explained the movement’s outreach efforts by saying Islam provided “a religion for Muslims and a civilization for non-Muslims.” [2]

After nine years in notorious prisons like Liman al-Turra and Abu Za’bal, Ezzat was released in 1974. Ezzat has noted that the cycle of arrests, torture and imprisonment of MB leaders in pre-revolution Egypt always increased membership and public support: “Regime repression is the glue that binds us together and reflects that we are on the right path.” [3]

After his release, Ezzat became a member of the all-important MB Guidance Bureau in 1981 before fleeing President Anwar Sadat’s crackdown on the MB in 1981. Ezzat traveled to Yemen, where he taught at the University of Sana’a, before moving on to England for several years of post-graduate studies (Egypt Today, November 26, 2017; al-Arabiya, November 23, 2017). [4]

By the mid-1980s, a conservative trend within the movement led by Ezzat and other figures who had emerged from prison or returned from exile drove many leading reformers from roles of influence. The ascendancy of the conservatives continued until the early 2000s, by which time Ezzat and conservative businessman Khayrat al-Shater dominated the ideological direction of the movement. [5] Ezzat was responsible for student recruitment and organizing movement cells across Egypt while working as a professor at the University of Zaqaziq’s faculty of medicine.

In 1992 Ezzat was arrested in connection with the “Salsabil Case,” in which security services claimed to have discovered documents detailing plans to overthrow the Mubarak regime in the offices of the Salsabil software company established by Khayrat al-Shater with Ezzat’s assistance. Two years later Ezzat was detained again alongside 153 other Ikhwan charged with plotting to depose the regime.

The Revolution

Ezzat served as MB secretary general from 2001 to 2010. During that time, he became a prominent supporter of Khayrat al-Shater. Ezzat and other conservatives skilfully squeezed out or tamed the movement’s leading reformers in 2009-2010 and elected Muhammad Badi’e as the new supreme guide, replacing Mahdi ‘Akif, who was persuaded to step down. [6] Also forced out was ‘Akif’s first deputy, Muhammad Habib, who accused Ezzat of mounting a coup against him. [7]

By the time of the 2011 revolution, the movement was firmly in the hands of a conservative trend embodied by Ezzzat, al-Shater and MB spokesman Mahmud Ghuzlan. Reformers began to flow out of the movement, a process accelerated by the events of the revolution and the uncertain response of the Brotherhood’s leadership.

Khayrat al-Shater (al-Arabiya)

Khayrat al-Shater (al-Arabiya)

Mubarak’s overthrow allowed the MB to form a political party for the first time in June 2011, the Ḥizb al-Ḥurriya wa’l-’Adala (Freedom and Justice Party – FJP). Ezzat’s ally Khayrat al-Shater became the FJP’s post-revolution candidate for president until his disqualification and replacement by Muhammad al-Mursi, who won the presidential election.

As al-Mursi was not the head of the Brotherhood, it remained unclear whether the Egyptian president was still answerable to the movement’s supreme guide. Despite efforts to portray the FJP as an autonomous political party, the Guidance Bureau’s importance became clear when Mursi and two other FJP leaders began to meet weekly with MB deputy supreme guides Ezzat, al-Shater, Ghuzlan and secretary general Mahmud al-Hussein to “coordinate” political activities. [8]

One consequence of the 2011 revolution was that the MB’s shura council was able to meet for the first time since 1995 without fear of arrest. During that time the Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau (including Ezzat) made all the movement’s major decisions without input from the broader leadership. Yet even as the Brotherhood’s new political wing tried to convince Egyptians of their commitment to democracy and tolerance of different perspectives, Ezzat shocked many Egyptians by making remarks endorsing the implementation of hudud punishments such as stoning, amputation and crucifixion for certain offenses under Shari’a. [9]

The Military Targets the Brotherhood

Following days of public protest, the July 3, 2013 military coup d’état brought an end to Mursi’s administration and yet another wave of anti-Ikhwan repression. The Brothers’ insistence that the FJP was the legitimate and democratically elected government of Egypt was largely ignored by the international community.

Attempts by the Brotherhood to apply pressure on the military through public protests and sit-ins were met with a savage response by government security forces who killed hundreds and arrested thousands to make it clear to the movement and its supporters that the Brotherhood was no longer part of Egypt’s political process.

With supreme guide Muhammad Badi’e and deputy guides al-Shater and Rashad al-Bayumi in prison, Ezzat became the movement’s acting supreme guide in August 2013 (al-Arabiya, August 20, 2013). Kamal Helbawy, a former MB guidance bureau member who resigned in 2012 over the movement’s decision to run a presidential candidate, noted Ezzat’s affinity for “radical Qutbism” and questioned Ezzat’s appointment as the movement’s supreme guide: “Ezzat is a well-mannered, decent man; he is not a great public speaker and prefers to work in secret more than in public. … Given these characteristics, I don’t think that he is a suitable leader for the Muslim Brotherhood at this stage” (Al-Monitor, August 21, 2013).

Leadership in Exile

Ezzat evaded arrest, unlike his comrades Badi’e, Mursi and al-Shater, all of whom were sentenced to serve a variety of life sentences based on convictions for terrorism, armed opposition to the state and espionage on behalf of foreign countries (Arab News, November 15, 2017; Daily News Egypt, September 16, 2017; Ahram Online, December 30, 2017).

Egyptian media reports in August 2015 maintained that Ezzat had been replaced as acting supreme guide by his UK-based 80-year-old Guidance Bureau colleague, Ibrahim Munir Mustafa. Munir denied the report and insisted “Dr. Mahmud Ezzat is still the deputy supreme guide and acting supreme guide” (Middle East Monitor, August 10, 2015). After rumors regarding Ezzat’s alleged ill health, the claim resurfaced a year later (Youm7 [Cairo], September 22, 2016). However, there was no formal announcement, and Ezzat remained the acting supreme guide. [10]

Still insisting on the legitimacy of Mursi’s FJP government, Ezzat released a public letter from his place of concealment in August 2017 urging an escalation of violence against the al-Sisi regime. Admitting that the organization was “in pain,” Ezzat called for “victory and sovereignty or death and joy” (Egypt Today, August 14, 2017). The letter may have been designed to undercut the appeal to Ikhwan youth of the more militant Kamal faction of the Brotherhood that emerged after the military coup.

Muhammad Kamal (Middle East Monitor)

Muhammad Kamal (Middle East Monitor)

Muhammad Kamal, a member of the Guidance Bureau, led “special operations committees” engaged in violence intended to force out the new Egyptian regime. Kamal and another MB leader were both killed by shots to the head during a police raid in northern Cairo in October 2016 (Reuters, October 3, 2016). Nonetheless, Kamal’s followers (sometimes termed “the new guard”) attempted to take over the movement in December 2016 when they “dismissed” the existing guidance bureau and established their own “revolutionary” version, creating competing administrations within the movement (Mada Masr, March 22, 2017).

In early 2017 the Kamal faction announced that it would begin publishing internal assessments of the mistakes made by the movement’s leadership. Though this initiative of the MB’s youth wing was supported by Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the movement’s Qatari-based spiritual leader, the Brotherhood’s old guard was alarmed by the announcement. Ibrahim Munir reminded members that documents lacking the approval of Mahmud Ezzat did not represent the movement’s opinion (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], March 27, 2017).

The Kamal faction followed up with a report in March 2017 that was highly critical of the reaction of Ezzat and the movement’s old guard to the 2011 revolution, accusing the Brotherhood’s senior leaders of adopting a cautious and conservative stance rather than adhering to the revolutionary principles of MB founder Hassan al-Banna (Mada Masr, March 22, 2017).

In May 2017, the Kamal faction published a document they claimed would reveal that the Munir/Ezzat faction of the Brotherhood was recommending a pragmatic and conciliatory approach to the movement’s political isolation, both in Egypt and internationally. It was an apparent recognition that continued insistence on the legitimacy of the FJP government and the return of Mursi as president was preventing political re-integration. The Munir/Ezzat faction was urging ideological flexibility at a time of weakness in order to allow the movement to survive and avoid international condemnation as a terrorist organization (al-Arabiya, May 8, 2017).

The Egyptian government has rejected all Ikhwan attempts to restore the group, even in a diminished fashion. In August 2017, a Cairo court placed 296 Ikhwan on the national terrorist list and claimed Ezzat was forming a military wing for the movement that would focus on toppling the state and working alongside other extremists to target Coptic Christians (al-Arabiya, November 23, 2017). The charges were at odds with Ezzat’s protestations of MB peacefulness, in which Ezzat quoted Dr. Badi’e: “Our motto remains ‘Our non-violence is more powerful than bullets’” (Ikhwanweb.com, September 13, 2016).

Conclusion

Up until the time of his arrest, Ezzat insisted that there was still a future for the MB, which has now survived 90 years of confrontation with Egypt’s governments, though its fortunes have rarely been lower.

The disaster ushered in by the Brotherhood’s full-scale entry into national politics was met with confusion and dissension within the movement. The detention or dispersal of many Ikhwan prevents the movement from gathering to develop strategies to move forward. In the meantime, an aging and fugitive leadership has spent much of its time fending off internal challenges from younger members urging defiance rather than the gradualism of the old guard leadership, which still cherishes values like discipline and obedience.

After replacing Ezzat, Munir quickly announced that sweeping changes to the Brotherhood’s organization were imminent, though he added these changes had already been planned before Ezzat’s detention and they were only being announced now to galvanize the membership and “to let the regime know that the movement has not died” (Middle East Monitor, September 21, 2020).

In a TV appearance shortly after Ezzat’s arrest, Munir claimed that President al-Sisi had extended an offer of reconciliation through Field Marshal Muhammad Hussein Tantawi three or four years ago that would permit the release of imprisoned Muslim Brothers and allow fugitive Brothers to return to Egypt in exchange for recognition of the Sisi regime’s legitimacy. Munir said such recognition would be “a betrayal of the country” (Middle East Monitor, September 21, 2020).

Munir also has experience with Egypt’s notorious prison system, serving 10 years after a 1965 death sentence was commuted, followed by a five-year sentence issued in absentia in 2009, though the sentence was lifted in 2012 under an amnesty issued by former President Muhammad al-Mursi (Al-Ahram Weekly [Cairo], September 10, 2020). Munir was granted asylum in England in the early 1980s and has directed the International wing of the Brotherhood from an office in London since then, a position that gave him control of a significant part of the movement’s financing. With the Brotherhood at a crossroads, the 83-year-old Munir seems an unlikely candidate to electrify the movement’s remaining membership in a way that would enable the Brotherhood to resist and overcome opposition from the Egyptian regime, the international community, and even within the movement itself. Without further changes to the leadership, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood appears ready to enter a period of significant and inevitable decline.

Notes

- Hesham al-Adawi, “Islamists in Power: The Case of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt,” in Khair El-Din Haseeb (ed.): State and Religion in the Arab World, Routledge, 2017, pp. 193-94.

- Eric Trager, Arab Fall: How the Muslim Brotherhood Won and Lost Egypt in 891 Days, Georgetown University Press, 2016, p. 94.

- Khalil al-Anani, Inside the Muslim Brotherhood: Religion, Identity, and Politics, Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 142-43.

- Ibid, p. 151.

- Ezzat knew al-Shater from his days in al-Sana’a and London.

- Hazem Kandil: Inside the Brotherhood, Cambridge, 2015, pp. 136-37; Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement, Princeton University Press, 2013, pp. 139-40.

- Khalil al-Anani, op cit, pp. 153-54.

- Eric Trager, op cit, p. 111.

- Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement, Princeton University Press, 2013, p.186.

- Nearly a year after this last alleged transfer of authority, Munir signed a statement regarding the Manchester terrorist attack as “Deputy Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood” (Middle East Monitor, May 23, 2017).