Andrew McGregor

Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(121)

August 8, 2024

Executive Summary:

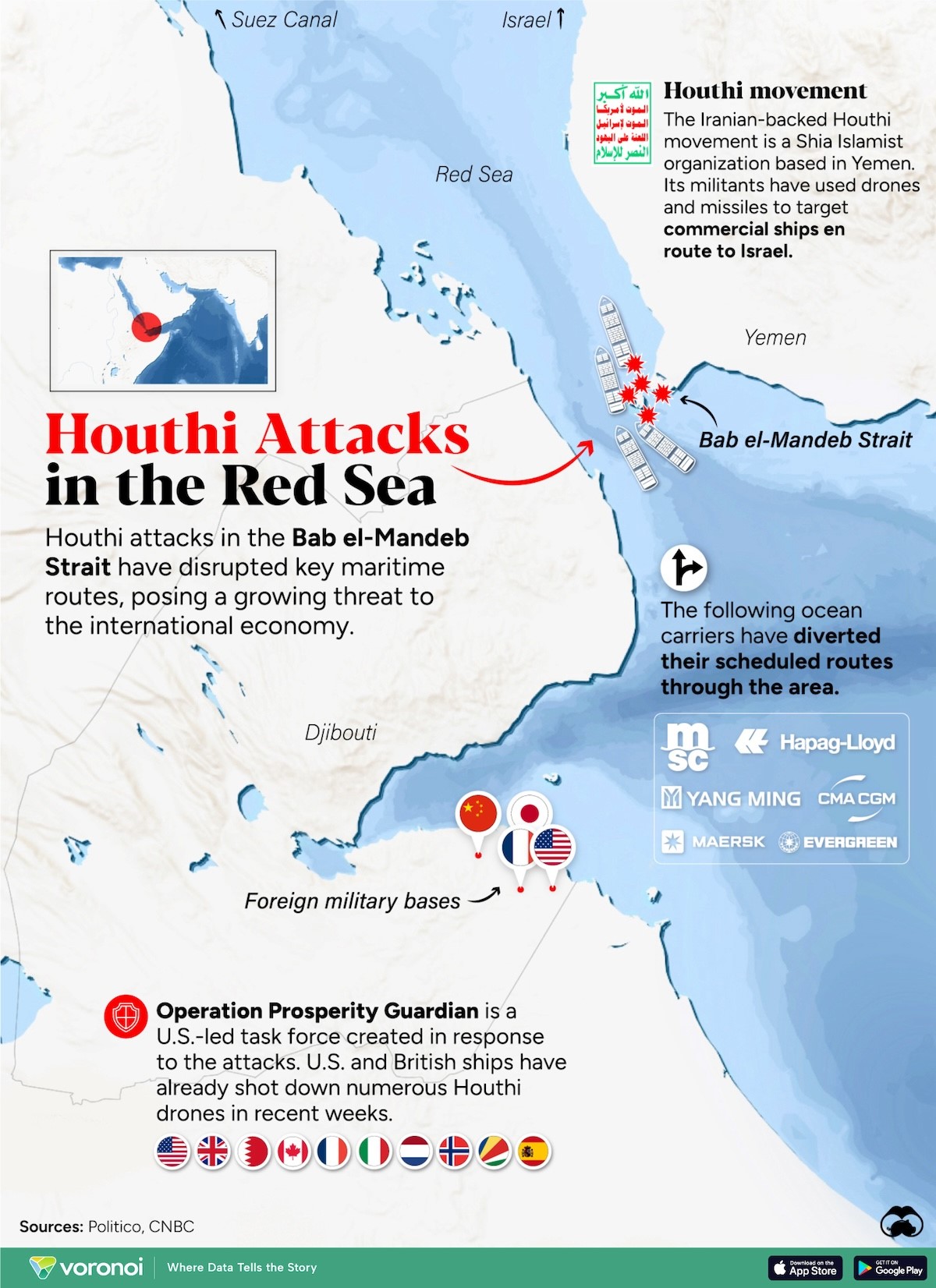

- Since the United States authorized Kyiv to use Western-provided weapons on Russian territory, Moscow has considered striking back on a new front by providing modern anti-ship missiles to Yemen’s Houthis (Ansarallah), who have been striking shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

- Aside from the apparent threat to Western interests, Moscow’s sending of missiles to Yemen could present substantial risks to Russia and its relations with traditional partners in the region, including Iran and Saudi Arabia.

- Any attempt by Moscow to turn Ansarallah into a Russian auxiliary in its war on Ukraine will only encourage heavier strikes on Yemen by US aircraft without providing tangible benefits to the movement.

On August 2, a senior US official reported that members of the Main Directorate of the Russian General Staff (GRU) are operating in the Houthi-controlled territory of Yemen in an advisory role to Yemen’s Houthi movement, Ansarallah. The report claims that GRU officers have been operating in Yemen for “several months” to assist the Houthis in targeting commercial shipping (Middle East Eye, August 2). Ansarallah has been striking shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden for over eight months in support of Gaza’s Hamas movement. Primarily using drones and missiles provided by Iran, the Houthi attacks are intended to interfere with the movement of Israeli ships or cargoes, as well as those of Israel’s main backers, the United States and the United Kingdom. The latter two powers also provide military aid and intelligence to Ukraine in its resistance to the Russian invasion. When the United States gave Kyiv permission to use new weapons provided by the US-led Western alliance to strike targets inside Russia, Moscow began to consider striking back on a new front by providing modern anti-ship missiles to Yemen’s Houthis (Middle East Eye, June 28). The provision of sophisticated arms for Houthi use against Western shipping would represent a dangerous expansion of the conflict in Ukraine that could not easily be reversed.

On August 2, a senior US official reported that members of the Main Directorate of the Russian General Staff (GRU) are operating in the Houthi-controlled territory of Yemen in an advisory role to Yemen’s Houthi movement, Ansarallah. The report claims that GRU officers have been operating in Yemen for “several months” to assist the Houthis in targeting commercial shipping (Middle East Eye, August 2). Ansarallah has been striking shipping in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden for over eight months in support of Gaza’s Hamas movement. Primarily using drones and missiles provided by Iran, the Houthi attacks are intended to interfere with the movement of Israeli ships or cargoes, as well as those of Israel’s main backers, the United States and the United Kingdom. The latter two powers also provide military aid and intelligence to Ukraine in its resistance to the Russian invasion. When the United States gave Kyiv permission to use new weapons provided by the US-led Western alliance to strike targets inside Russia, Moscow began to consider striking back on a new front by providing modern anti-ship missiles to Yemen’s Houthis (Middle East Eye, June 28). The provision of sophisticated arms for Houthi use against Western shipping would represent a dangerous expansion of the conflict in Ukraine that could not easily be reversed.

The weapons in question are believed to be P-800 Oniks supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles. These sea-skimming missiles fly 10 to 15 meters (32 to 50 feet) above the water at a top speed of 1,860 miles per hour, making them extremely difficult to evade or intercept. In the absence of a Ukrainian fleet, Moscow may calculate it can put some of its anti-ship missiles to better use against Ukraine’s supporters on another front. Previously, the Kremlin had called on Ansarallah to abandon the practice of firing on international shipping in the Red Sea while condemning the US and UK counterstrikes as an “Anglo-Saxon perversion of UN Security Council resolutions” (The Moscow Times, January 12).

The Houthis currently rely on less than precise open-source intelligence to identify maritime targets, leading to strikes on vessels with ties to both Iran and Russia (Press TV [Tehran], July 20). In March, Russian and Chinese diplomats met with Houthi representatives in Oman, receiving assurances that their ships in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden could pass unmolested in return for diplomatic support in the United Nations (Bloomberg, March 21). While Chinese and Russian shipping continue to use the Red Sea passage, other transporters face surging insurance rates or additional costs posed by rounding the Cape of Good Hope as an alternative route.

Oil tanker Chios Lion, carrying Russian oil to China, is attacked by a Houthi missile on July 15, 2024 (Yemeni Military Media).

Oil tanker Chios Lion, carrying Russian oil to China, is attacked by a Houthi missile on July 15, 2024 (Yemeni Military Media).

On July 18, Yemen’s “Leader of the Revolution” Sayyid ‘Abd al-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi claimed that the strikes on US and UK shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden were inflicting economic damage on those countries as well as Israel. He added that Yemen was seeking to spread its maritime operations to the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea (SABA [Yemen], July 18).

Aside from the apparent threat to Western interests, a Russian gift of missiles to Yemen could present unforeseen but substantial risks to Russia itself and its foreign relations:

- The possibility is growing that new Russian anti-ship missiles could be used against Saudi shipping, reigniting hostilities in an unresolved war that began in 2015. Russia maintains close relations with Saudi Arabia as partners in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries “Plus” group (OPEC+). According to US intelligence sources, Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman has requested that Moscow not go through with the delivery of cruise missiles to Yemen (Middle East Eye, June 28; Press TV [Tehran], July 20).

- Despite Russia’s alliance with Iran, Moscow has maintained cordial relations with Israel throughout the Gazan campaign. The July 19 Houthi drone strike on Tel Aviv, however, has turned the Yemeni threat on territorial Israel from potential to real. In its present combative state, frustrated by an inability to defeat a small and lightly armed militia in Gaza, Israel may seek to eliminate new threats to its territory as quickly as possible, as indicated by its retaliatory strike on Yemen’s Red Sea Port of Hudaydah. Russia’s closeness to Iran is an existing irritant in relations with Israel. Providing the Houthis with superior anti-ship missiles could mean a complete break with Israel. Washington is already pressuring Tel Aviv to ship eight older Patriot air defense systems (via the United States) to Ukraine for use against Russian missiles (Times of Israel, June 28).

- The Kremlin runs the risk of creating friction with Tehran, which exerts a strong influence over the Houthi movement that it may not care to share with Moscow.

- Moscow’s involvement at any level in attacks on Red Sea shipping will complicate Russian efforts to establish a permanent Red Sea presence in Sudan, which relies on its Red Sea port as the main commercial conduit to the outside world (see EDM, November 14, 2023).

- Russian military trainers and advisors could become targets (intentional or not) of US and Israeli strikes to prevent the deployment of Russian missiles. This could easily lead to escalation and a danger of becoming embroiled in a wider Middle Eastern conflict. Yemen has already announced plans for closer cooperation with countries of the “Resistance” axis (Al Jazeera, June 26).

For all its threats to the West and its aggression in Ukraine, Moscow does not perceive itself as a rogue state. Providing anti-ship missiles to a military force that it does not fully control would endanger not only international shipping in one of the world’s most important shipping channels but Russia’s reputation as well.

Any attempt by Moscow to turn Ansarallah into a Russian auxiliary in its war on Ukraine will only encourage heavier strikes on Yemen by US aircraft and the specific targeting of Ansarallah leaders without providing tangible benefits to the movement. The Kremlin may also discover that becoming allies with the religiously inclined Houthi movement could prove difficult in practice. Previous (Soviet) Russian experience in Yemen was with socialist southerners whose successors in the United Arab Emirates-backed Southern Transitional Council continue to insist they form Yemen’s true government.

US diplomatic efforts through a third party to persuade Russia to back off from these deliveries are ongoing. Aware of the reports that Russia was considering the transfer of anti-ship missiles to Yemen, Russia’s UN representative declared on July 23 that Moscow “stands with the security and safety of global navigation in the Red Sea” (SABA [Yemen], July 25). Those remarks may indicate the Kremlin could be having second thoughts about a policy decision made quickly and emotionally.