Andrew McGregor

Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, John Hopkins University

February 26, 2003

BACKGROUND:

A native of southern Saudi Arabia, al-Walid’s real name is ‘Abd al-Aziz al-Ghamidi. In 1987, al-Walid left for Peshawar, the transit point for Arab volunteers heading into Afghanistan. There, he would have received training and support from the Mukhtab al-Khidmat, an organization run by Dr. ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam and funded by Osama bin Laden. As the Afghan war wound down, al-Walid made a short trip home before volunteering for new jihad operations in Bosnia in 1993.

Amir Abu al-Walid (al-Jazeera)

Amir Abu al-Walid (al-Jazeera)

In June of 2002, the London-based Saudi newspaper al-Majallah published an interview with al-Walid’s family in Saudi Arabia. His family revealed that he was pious but religiously moderate, one of eleven sons, and once had a taste for acting, but had little to say about his days in Afghanistan. In Bosnia, al-Walid may have served alongside some 300 veterans of the Afghanistan war. While they proved effective fighters, they were joined by hundreds of other foreign Muslims whose military skills were questionable, and whose religious Puritanism antagonized tolerant Bosnian Muslims.

Many of the ‘Afghans’ were organized as part of the regular Bosnian Army’s 7th Battalion under the command of Abu ‘Abd al-Aziz ‘Barbaros’, an Indian Muslim with experience in Afghanistan and Kashmir. When the Dayton Accords made the mujahidin presence in Bosnia politically uncomfortable, several hundred of the ‘Afghans’ began transferring to Chechnya in late 1995. Al-Walid may have served with Khattab in Chechnya as early as March 1995, planning and participating in some of the war’s most successful actions against Russian convoys. In the role of Khattab’s naib (deputy), he joined the 1999 attack on Dagestan that contributed to sparking the current war. In April 2000 he led a successful attack on the Russian 51st Paratroop regiment.

In May 2002 came reports that al-Walid was holding the captured crew of a Mi-24 helicopter hostage, threatening to kill them if the Russians did not release 20 jailed Chechens. There are allegations that al-Walid is variously an agent of Saudi intelligence, the Muslim Brotherhood, or Bin-Laden’s al-Qaeda. The FSB claims that al-Walid organized the 1999 Russian apartment-block bombings, planned bacteriological attacks on Russia, and was behind the May 2002 Kaspiysk bombing in Daghestan.

IMPLICATIONS:

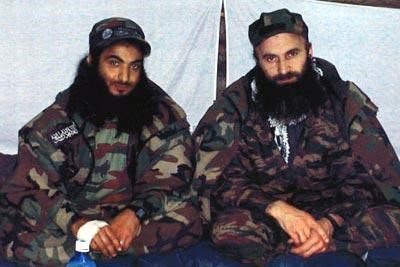

In September 2002, questions were raised as to al-Walid’s actual existence. The Director of the American Committee for Peace in Chechnya claimed that Akhmed Zakayev and other representatives of the Maskhadov government had told him there was no such person as Abu al-Walid. Russian journalist Anna Politkoyskaya (one of the few outsiders to report from behind Chechen lines) was quoted as saying none of the fighters she knew had ever seen al-Walid. Further complicating the picture were numerous reports that al-Walid had drowned in June 2002 while crossing the Khul-Kulao River by horse. The first known pictures of al-Walid appeared on Movladi Udagov’s Kavkaz (Caucasus) website. The site showed a youthful looking al-Walid posing with Basayev, Maskhadov and other leaders of the Chechen rebellion.

Abu al-Walid with Chechen Field Commander Shamyl Basayev

Abu al-Walid with Chechen Field Commander Shamyl Basayev

Al-Walid affects the long hair and beard popular with the late al-Khattab and other Arab mujahidin in Chechnya. Russia blames Abu al-Walid and Shamil Basayev for the devastating December 27 truck-bombing of the Chechen administration building in Grozny, allegedly carried out with funding from the Muslim Brotherhood. Russian officials claimed that the ‘Arab methods’ used in the suicide-bombing pointed to ‘Arab militants trained in Afghanistan’. The Muslim Brotherhood has vigorously denied any responsibility for the Grozny bombing or other violent acts, though they are likely involved in fund-raising for the Chechen mujhadin as well as their acknowledged funding of humanitarian organizations active in Chechnya.

Al-Walid appears to be serving as deputy to Basayev, the Amir of the Majlis al-Shura. Basayev has resigned his command, however, since admitting responsibility for the disastrous events in Moscow. Officially, Basayev is now nothing more than the commander of the Riyadus- Salakhin Suicide Battallion, a newly formed unit of radical Islamists. Al-Walid continues as Commander of Eastern Front operations. The mujahidin under al-Walid are multi-ethnic in origin. Besides Arabs from the Gulf region and North Africa, there have at times been volunteers from Turkey, other parts of the Russian North Caucasus, Central Asia, Western Europe and even Japan. The composition of the group is fluid but is hard pressed at present to insert new members. A group of about 80 Arabs may have entered Chechnya last Fall.

There are also claims that many Saudi-sponsored Arabs active in Chechnya have recently relocated to the Middle East due to the failure of the Salafists to gain popular support in the Caucasus. Khattab understood the importance of public relations, realizing that in order to keep funds coming, the Chechen jihad had to be visible. A videotape team always accompanied Khattab’s operations, and the Amir frequently made himself available for interviews (by satellite phone or other means) to the Muslim media. Al-Walid’s more secretive style may jeopardize the mujahidin’s financial links.

CONCLUSIONS:

Russian allegations of al-Qaeda control of al-Walid and the Arab fighters (and lately, the entire Chechen rebellion) make for useful propaganda, intended to draw American support. These charges rest on the belief that Bin Laden controls the thoughts and actions of every militant in the Islamic world. Since his death, Khattab’s military career has been compared favorably to Bin Laden’s by some of the most radical shaykhs in Saudi Arabia. While Khattab was a constant presence on the battlefield and never pretended to be a scholar of Islam, Bin Laden has pretensions of religious leadership and has brought destruction upon Muslim lands. Khattab strongly denied any al-Qaeda connections to his command.

The importance of the Arab fighters in the Chechen war may actually be diminishing at the same time as Russian authorities are trying to emphasize it. While their numbers are too small to affect the fight one way or another, they remain important in command roles and as conduits to those in the Islamic world willing to support the struggle. Unlike the Russians, the Chechens have a very limited pool of manpower to draw upon, making it nearly impossible to refuse the help of any trained volunteer. Veterans of Afghanistan were initially important in training Chechen rebels, but such training is no longer needed, as Chechens have mastered their own tactics and weaponry. Shrinking financial support from the Gulf States may further reduce the influence of the Arab mujahidin in Chechnya.