Andrew McGregor

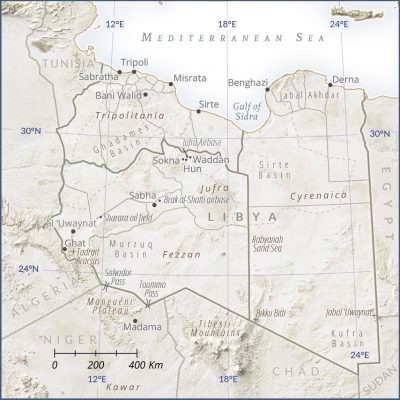

Abstract: Libya’s relentless post-revolution conflict appears to be heading for a military rather than a civil conclusion. The finale to this struggle may come with an offensive against the United Nations-recognized government in Tripoli by forces led by Libya’s ambitious strongman, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. However, the conflict will continue if Haftar is unable to consolidate control of the southern Fezzan region, the source of much of the oil and water Libya’s coastal majority needs to survive. Contesting control of this vital region is an aggressive assortment of well-armed jihadis, tribal militias, African mercenaries, and neo-Qaddafists. Most importantly, controlling Fezzan means securing 2,500 miles of Libya’s porous southern desert borders, a haven for militants, smugglers, and traffickers. The outcome of this struggle is of enormous importance to the nations of the European Union, who have come to realize Europe’s southern borders lie not at the Mediterranean coast, but in Libya’s southern frontier.

As the territory controlled by Libya’s internationally recognized government in Tripoli and its backers shrinks into a coastal enclave, the struggle for Libya appears to be entering into a decisive phase. Libyan strongman Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar claims his forces are now in control of 1,730,000 square kilometers out of Libya’s total of 1,760,000 square kilometers.1 However, to control Tripoli and achieve legitimacy, Haftar must first control its southern approaches through the Fezzan region. Europe and the United Nations recognize the Tripoli-based Presidential Council/Government of National Accord (PC/GNA) as the official government of Libya, but recognition has done nothing to limit migrant flows to Europe. Whoever can control these flows will be the beneficiary of European gratitude and diplomatic approval.

Securing Tripoli means preventing armed elements supporting the PC/GNA from fleeing into the southern desert. Haftar must control water pipelines (the “Man-Made River Project”) and oil pipelines from the south, secure the borders, and prevent Islamic State fighters, pro-Qaddafists, Islamist militias, and foreign mercenaries from turning Fezzan into a generator for continued instability in Libya.

Fezzan is a massive area of over 212,000 square miles with a mostly tribal population of less than 500,000 living in isolated oases or wadi-s (dry riverbeds, often with subsurface water). Hidden by sand seas and rocky desert are the assets that make Fezzan so strategically desirable: vital oil fields, access to massive subterranean freshwater aquifers, and a number of important Qaddafi-era military airbases. A principal concern is the ability of radical Islamists to exploit Fezzan’s lack of security to further aims such as territorial control of areas of the Sahara/Sahel region or the facilitation of potential terrorist strikes on continental Europe. Many European states are closely watching the outcome of this competition due to the political impact of the large number of sub-Saharan African migrants passing through Fezzan’s unsecured borders on their way to eventual refugee claims in Europe.

Fezzan is a massive area of over 212,000 square miles with a mostly tribal population of less than 500,000 living in isolated oases or wadi-s (dry riverbeds, often with subsurface water). Hidden by sand seas and rocky desert are the assets that make Fezzan so strategically desirable: vital oil fields, access to massive subterranean freshwater aquifers, and a number of important Qaddafi-era military airbases. A principal concern is the ability of radical Islamists to exploit Fezzan’s lack of security to further aims such as territorial control of areas of the Sahara/Sahel region or the facilitation of potential terrorist strikes on continental Europe. Many European states are closely watching the outcome of this competition due to the political impact of the large number of sub-Saharan African migrants passing through Fezzan’s unsecured borders on their way to eventual refugee claims in Europe.

Competing Governments, Competing Armies

The security situation in Fezzan and most other parts of Libya became impossibly complicated by the absence of any unifying ideology other than anti-Qaddafism during the 2011 Libyan revolution. Every attempt to create a government of national unity since has been an abject failure.

At the core of this political chaos is the United Nations-brokered Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) of December 17, 2015, which called for a tripartite government consisting of a nine-member Presidency Council (PC) to oversee the functions of head-of-state, a Government of National Accord (GNA) as the executive authority, and a House of Representatives (HoR) as the legislative authority with a High Council of State as a consultative body. In practice, most of these bodies are in conflict with each other or enduring high levels of internal dissension, leaving the nation haphazardly governed by scores of well-armed ethnic, tribal, and religious militias, often grouped into unstable coalitions. Contributing to the disorder is Khalifa Ghwell’s Government of National Salvation (GNS), which claims to be the legitimate successor of Libya’s General National Congress government (2014-2016) and makes periodic attempts to seize power in Tripoli, most recently in July 2017.2

The most powerful of the military coalitions is the ambitiously named Libyan National Army (LNA), a coalition of militias nominally under the Tobruk-based HoR and commanded by Khalifa Haftar, a Cyrenaïcan strongman who lived in Virginia after turning against Qaddafi but is now supported largely by Russia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). It is this author’s observation that Haftar has a habit of speaking for the HoR rather than taking direction from it.

The Tripoli-based PC, which has military authority under the LPA, is still trying to organize a national army. In the meantime, it is backed by various militias based in Misrata and Tripoli. Together with the GNA, it forms the internationally recognized government of Libya but still requires a majority vote from the Tobruk-based HoR to be fully legitimate under the terms of the LPA. There are even divisions within the seven-member PC, with three members now opposing PC chairman Fayez Serraj and supporting the HoR and Haftar.3

Fezzan’s Tribal Context

Fezzan’s human dimension consists of a patchwork of often-overlapping tribal and ethnic entities prone to feuds and shifting alliances. These might broadly be said to belong to one of four groups:

- Arab and Arab-Berber, consisting of the Awlad Buseif, Hasawna, Magarha, Mahamid, Awlad Sulayman, Qaddadfa, and Warfalla groups. The last three include migrants from the Sahel, descendants of tribal members who fled Ottoman or Italian rule and returned after independence. These are known collectively as Aïdoun (“returnees”);4

- Berber Tuareg, being the Ajjar Tuareg (a Libyan-Algerian cross-border confederation) and Sahelian Tuareg (typically migrants from Mali and Niger who arrived in the Qaddafi era);

- Nilo-Saharan Tubu, formed by the indigenous Teda Tubu, with smaller numbers of migrant Teda and Daza Tubu from Chad and Niger. These two main Tubu groups are distinguished by dialect;

- Arabized sub-Saharans known as Ahali, descendants of slaves brought to Libya with little political influence.

The LNA’s Campaign in Jufra District

The turning point of Haftar’s attempt to bring Libya under his control came with his takeover of the Jufra district of northern Fezzan, a region approximately 300 miles south of Tripoli with three important towns in its northern sector (Hun, Sokna, and Waddan), as well as the Jufra Airbase, possession of which brings Tripoli within easy range of LNA warplanes.

Al-Wahat Hotel in Hun after LNA airstrikes (Libya Observer)

Al-Wahat Hotel in Hun after LNA airstrikes (Libya Observer)

The campaign began with a series of airstrikes by LNA and Egyptian aircraft in May 2017 on targets in Hun and Waddan belonging to Abd al-Rahman Bashir’s 613th Tagreft Brigade (composed of Misratans who had fought the Islamic State in Sirte as part of the Bunyan al-Marsous [“Solid Structure”] coalition)5 and the Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB),a the latter allegedly supported by a group of Chadian mercenaries. In early June 2017, the LNA’s 12th Brigade swept into the Jufra airbase with the help of local tribal leaders.6 Opposition was slight after the Misratan 13th Brigade and the BDB pulled out toward Misrata.

This allowed the LNA to take the town of Bani Walid, an important center in Libya’s human trafficking network strategically located 100 kilometers southwest of Misrata and 120 kilometers southeast of Tripoli. The site offers access by road to both cities and will be home to the new 27th Light Infantry Brigade commanded by Abdullah al-Warfali (a member of the Warfala tribe) as part of the LNA’s Gulf of Sidra military zone under General Muhammad Bin Nayel.7 Possession of Bani Walid could allow the LNA to separate the GNA government in Tripoli from its strongest military supporters in Misrata.

An Opening for Islamist Extremists

North African jihadis are likely to use the political chaos in Fezzan to establish strategic depth for operations in Algeria, Niger, and Mali. Those militants loyal to al-Qa`ida united in the Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin (JNIM) on March 2, 2017, as a merger of Ansar al-Din, al-Mourabitoun, the Macina Liberation Front, and the Saharan branch of al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). The group’s Tuareg leader, Iyad ag Ghali, will look to exploit Libyan connections in Fezzan already established by al-Mourabitoun chief Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who mounted his attack on Algeria’s In Amenas gas plant in 2013 from a base near al-‘Uwaynat in Fezzan.b For now, it appears Ag Ghali can count on only minimal support from the Sahelian Tuareg community in Fezzan, which largely favors Qaddafism over jihadism.c

The rival Islamic State announced the establishment of the wilaya (province) of Fezzan as part of its “caliphate” in November 2014.d Since their expulsion from Sirte last December by al-Bunyan al-Marsous and intensive U.S. airstrikes, Islamic State fighters now range the rough terrain south of the coast, presenting an elusive menace.8 Following the interrogation of a large number of Islamic State detainees, the Attorney General’s office in Tripoli announced that Libyans were a minority in the group, with the largest number having come from Sudan, while others came from Egypt, Tunisia, Mali, Chad, and Algeria.9

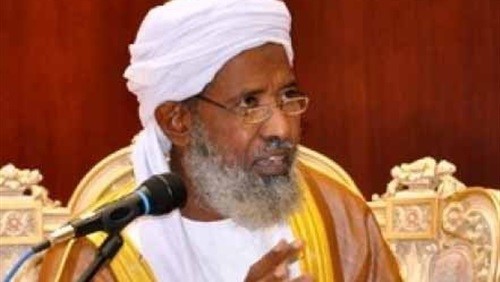

Masa’ad al-Sidairah (Sudan Tribune)

Masa’ad al-Sidairah (Sudan Tribune)

Some Sudanese Islamic State fighters are disciples of Sudanese preacher Masa’ad al-Sidairah, whose Jama’at al-I’tisam bil-Quran wa’l-Sunna (Group of Devotion to the Quran and Sunna) publicly supported the Islamic State and its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi until a wave of arrests forced it to pledge to abandon Islamic State recruitment in Sudan for the Libyan and Syrian battlefields.10 Sudanese authorities state that at least 20 Sudanese Islamic State recruits have been killed in Libya.11 Many of these entered Libya via the smugglers’ route passing Jabal ‘Uwaynat at the meeting point of Egypt, Sudan, and Libya.12

Other Islamic State fighters fleeing Sirte headed into Fezzan, where they were reported to have concentrated at the town of al-‘Uwaynat, just north of Ghat and close to the Algerian border. This group was believed responsible for the February 2017 attacks on Great Man-Made River facilities and electricity infrastructure, including the destruction of almost 100 miles of electricity pylons between Jufra and Sabha.13 e On May 6, 2017, Islamic State militants mounted an ambush on a Misratan Third Force convoy on the road between Jufra and Sirte, killing two and wounding three.14 Libyan investigators claim the Islamic State has rebuilt a “desert army” of three brigades under the command of Libyan Islamist al-Mahdi Salem Dangou (aka Abu Barakat).15

Islamic State fighters shattered any thought their Sirte defeat left the group in Libya incapable of mounting operations on August 23, 2017 with an attack on the LNA’s 121st Infantry Battalion at the Fugha oasis (Jufra District). Nine soldiers and two civilians were apparently killed after capture by close range shots to the head or by having their throats slit. Most of the soldiers were former members of Qaddafi’s elite 32nd Mechanized Brigade from Surman and may have been targeted due to the role of Surmani troops in wiping out Islamic State terrorists who had briefly occupied the town of Sabratha, in between Tripoli and the border with Tunisia, in February 2016.16

Securing the Southern Borders

Control of the trade routes entering Fezzan was based on the midi-midi (friend-friend) truce of 1893, which gave the Tuareg exclusive control of all routes entering Fezzan west of the Salvador Pass (on the western side of Niger’s Mangueni plateau), while the Tubu controlled all routes from Niger and Chad east of the Toumou Pass on the eastern side of the plateau.17 The long-standing agreement collapsed during the Tubu-Tuareg struggles of 2014, fueled by clashes over control of smuggling operations and the popular perception of the Tuareg as opponents of the Libyan revolution.

Today, both passes are monitored by American drones operating out of a base north of Niamey and by French Foreign Legion patrols operating from a revived colonial-era fort at Madama, 60 miles south of Toummo.18 Chad closed its portion of the border with Libya in early January 2017 to prevent Islamic State militants fleeing Sirte from infiltrating into north Chad, but has since opened a single crossing.19

On a September 2017 visit to Rome, Haftar insisted the international arms embargo on Libya must be lifted for the LNA, adding that he could provide the manpower to secure Libya’s southern border, but needed to be supplied with “drones, helicopters, night vision goggles, [and] vehicles.”20 Haftar said earlier that preventing illegal migrants from crossing the 2,500-mile southern border would cost $20 billion.21

Some southern militias have proven effective at ‘policing’ the border when it is in their own interest; a recent fuel shortage in southern Fezzan was remedied when the Tubu Sukour al-Shara (“Desert Eagles”) militia, which is based in Qatrun some 200 kilometers south of Sabha, closed the borders with Chad and Niger on September 7, 2017, and began intercepting scores of tanker trucks smuggling fuel and other goods across the border into Niger, where they had been fetching greater prices, but leaving Fezzan with shortages and soaring prices.22

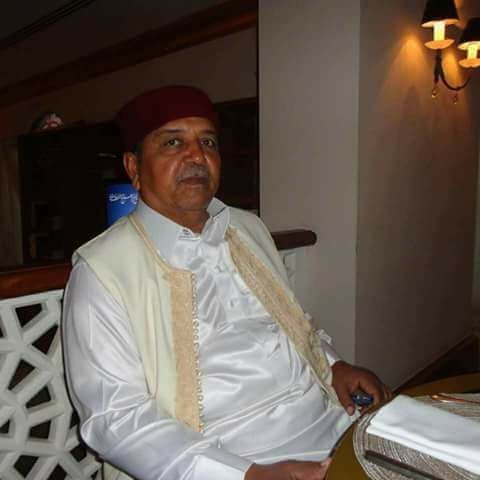

Sukour al-Sahra leader Barka Shedemi

Sukour al-Sahra leader Barka Shedemi

Sukour al-Sahra is led by a veteran Tubu warrior from Niger, Barka Shedemi, and has support from the HoR.23 Equipped with some 200 vehicles ranging over 400 miles of the southern borders, Shedemi is said to have strong animosity toward the Qaddadfa tribe after he was captured by them in the 1980s and turned over to the Qaddafi regime, which punished him as a common brigand by cutting off a hand and a leg.24 Shedemi has reportedly asked for a meeting with Frederica Mogherini, the European Union’s top diplomat, to discuss compensation for his brigade in exchange for halting migrant flows across Libya’s southern border.25

Foreign Fighters in Fezzan

Since the revolution, there has been a steady stream of reports concerning the presence of Chadian and Darfuri fighters in Libya, especially those belonging to Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). JEM leaders were once harbored by Qaddafi in their struggle against Khartoum, and took refuge in Libya after the revolution as pressure from the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) forced the rebels across the border. Khartoum backs the PC/GNA and has complained of JEM’s presence in Libya to the United Nations’ Libyan envoy.26

Haftar sees the hand of Qatar behind the influx of foreign fighters: “The Libyan army has recorded the arrival in Libya of citizens from Chad, Sudan, and other African and Arab states. They got into Libya because of the lack of border controls. They received money from Qatar, as well as other countries and terrorist groups.”27 Haftar’s statement reflects the deteriorating relations between Qatar and much of the rest of the Arab world as well as Haftar’s own indebtedness to his anti-Qatar sponsors in Egypt and the UAE. Haftar and HoR spokesmen have also claimed Qatar was supporting what it called terrorist groups (including the Muslim Brotherhood, Ansar al-Sharia, and the defunct Libyan Islamic Fighting Group) and carrying out a campaign of assassinations that included an unsuccessful attempt on Haftar’s life.28 f

Notwithstanding his complaints about JEM and other foreign fighters, Haftar is accused of employing JEM and Darfuri rebels of the Zaghawa-led Sudan Liberation Army-Minni Minnawi (SLA-MM), which arrived in Fezzan in 2015. Acting as mercenaries, these fighters participated in LNA campaigns in Benghazi and the oil crescent alongside members of SLA-Unity and the SLA-Abd al-Wahid, largely composed of members of the Fur ethnic group for which Darfur is named.29 When the SLA-MM returned to Darfur in May 2017, they were badly defeated by the RSF.30

Foreign fighters are alleged to have played a part in the June 2017 Brak al-Shatti airbase massacre of 140 LNA soldiers and civilians by the BDB and their Hasawna tribal allies, with a spokesman for the LNA’s 166th Brigade asserting the presence of “al-Qa`ida associated” Chadian and Sudanese rebels with the BDB.31 In the days after the Brak al-Shatti combat, the LNA’s 12th Brigade spokesman claimed that his unit had captured Palestinian, Chadian, and Malian al-Qa`ida members, adding that 70 percent of the fighters they had killed or taken prisoner were foreign.32 The claims cannot be verified, but many BDB commanders have ties to factions of al-Qa`ida and/or the Islamic State.

While Arab rivals of the Tubu in southern Libya often delegitimize local Tubu fighters by referring to them as “Chadian mercenaries,” there are actual Tubu fighters from Chad and Niger operating in various parts of Libya. Fezzan’s Tubu and Tuareg ethnic groups often take advantage of their ability to call upon their cross-border kinsmen when needed.33 Tubu leaders in Niger’s Kawar region complain that most of their young men have moved to Libya since 2011.34

Chadian rebels opposing the regime of President Idriss Déby Itno have established themselves near the Fezzan capital of Sabha as they build sufficient strength to operate within Chad.35 In mid-June 2017, artillery of the LNA’s 116th Infantry Battalion shelled Chadian camps outside Sabha (including those belonging to Mahamat Mahdi Ali’s Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad [FACT]) after accusing them of fighting on behalf of the PC/GNA. A U.N. report suggests that FACT fought alongside the BDB during the latter’s operations in the Libyan oil crescent in March 2017, losing a prominent commander in the process.36 A FACT splinter group, the Conseil de Commandement Militaire Pour le Salut de la Republique (CCMSR), also has a base near Sabha, which was attacked by LNA aircraft in April 2016.37

Efforts to Restore Border Security in Fezzan

Alarmed by the rising numbers of migrants trying to reach Europe from Libya and Libya’s inability to police its own borders, Italy and Germany called in May for the establishment of an E.U. mission to patrol the Libya-Niger border “as quickly as possible.”38 Ignoring its colonial reputation in Libya, Rome suggested deploying the Italian Carabinieri (a national police force under Italy’s Defense Ministry) to train southern security forces and help secure the region from Islamic State terrorists fleeing to Libya from northern Iraq.39

European intervention of this type is a non-starter for the PC/GNA government, which has made it plain it also does not see Libya as a potential holding tank for illegal migrants or have interest in any plan involving their settlement in Libya.40

In Fezzan, migrants are smuggled by traffickers across the southern border and on to towns such as Sabha and to its south Murzuq, ‘Ubari, and Qatrun in return for cash payments to the Tubu and Tuareg armed groups who control these passages. In 2017, the largest groups of migrants were from Nigeria, Bangladesh, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire.41 The main center of the trade is Sabha, where members of the Awlad Sulayman are heavily involved in human smuggling.42 The Tubu and Tuareg also run profitable but dangerous operations smuggling narcotics, tobacco, alcohol, stolen vehicles, state-subsidized products, and other materials across Libya’s borders. Street battles in Sabha are common between competing factions of traffickers.43

Italy has signed a military cooperation agreement with Niger that will allow it to deploy alongside Sahel Group of Five (SG5) forces (an anti-terrorist and economic development coalition of five Sahel nations with support from France and other nations) and French and German contingents with the objective of establishing control over the border with Libya.g On the Fezzan side of the border, Italy will support a border guard composed of Tubu, Tuareg, and Awlad Sulayman tribesmen as called for in a deal negotiated in Rome last April.44 Rome will, in turn, fund development projects in the region. Local leaders in Fezzan complain national leaders have been more interested in border security than the lack of development that fuels border insecurity, not realizing the two go hand-in-hand.45 Italian Interior Minister Marco Minniti noted his conviction that “the southern border of Libya is crucial for the southern border of Europe as a whole. So we have built a relationship with the tribes of southern Sahara. They are fundamental to the south, the guardians of the southern border.”46

A Failed Experiment

Proof that the migrant crisis cannot be solved on Libya’s coast came in September/October 2017 in the form of a 15-day battle in the port city of Sabratha (78 kilometers west of Tripoli) that killed 39 and wounded 300. The battle marked the collapse of an Italian experiment in paying militias to prevent migrants from boarding boats for Italy.47

Fighting in Sabratha, September 2017 (Libya Observer)

Fighting in Sabratha, September 2017 (Libya Observer)

The Italian decision to select the GNA-aligned Martyr Anas Dibbashi Brigade (aka 48th Infantry Brigade) to cut off migrant flows from Sabratha (which it did with some success) angered the Wadi Brigade (salafist followers of Saudi shaykh Rabi’ bin Hadi al-Madkhali who are aligned with the LNA)48 and the (anti) Islamic State-Fighting Operations Room (IFOR, consisting of pro-GNA former army officers, though some have ties to the Wadi Brigade). Like the Anas Dibbashi Brigade, both groups had made great sums of cash from human trafficking. With the southern border still unsecured, migrants continued to pour into Sabratha but could not be sent on to Europe, creating a trafficking bottleneck.49 Suddenly, only Anas Dibbashi was making money (in the form of millions of Euro from Italy),50 leading to a fratricidal struggle to restore the old order as members of Sabratha’s extensive Dibbashi clan fought on both sides of the conflict.h Both LNA and GNA forces claimed victory over the Anas Dibbashi Brigade, with Haftar claiming IFOR was aligned with his LNA.51 Following the battle, migrant flows resumed while Haftar warned his forces in Sabratha to be ready for an advance on Tripoli.52

The Fezzan Qaddafists

A challenge to Haftar’s efforts (and one he has tried to co-opt) is the strong current of Qaddafism (i.e., support of the Jamahiriya political philosophy conceived by Muammar Qaddafi) in Fezzan, the last loyalist area to be overrun in the 2011 revolution. Support for Qaddafi was especially strong in the Sahelian Tuareg, Qaddadfa, and parts of the Awlad Sulayman communities.

Fezzan’s Qaddafists were no doubt inspired by the release of Saif al-Islam al-Qaddafi in early June 2017 after six years of detention.53 Saif, however, is far from being in the clear; he remains subject to a 2015 death sentence issued in absentia in Tripoli and is still wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged war crimes committed in 2011.54 On October 17, 2017, the Qaddafi family lawyer announced Saif was already visiting tribal elders as he began his return to politics.55 The announcement followed a statement from the United Nations Special Envoy to Libya, Ghassan Salamé, that Libyan elections must be open to all, including Saif and other unreformed Qaddafists.56

General Ali Kanna Sulayman, a Tuareg Qaddafi loyalist, fled to Niger after the fall of Tripoli in 2011, but was reported to have returned to Fezzan in 2013.57 His former comrade, Qaddafi-era Air Force commander Ali Sharif al-Rifi, also returned from Niger to his Fezzan home of Waddan in June 2017.58 Thirty Qaddafi-era prisoners, mostly military officers, were released in early June 2017 by the Tripoli Revolutionaries’ Brigade (TRG) under orders from the HoR.59

General Ali Kanna took control of the massive Sharara oil field in Fezzan after the Misratan 13th Brigade pulled out in the last week of May 2017. As leader of a neo-Qaddafist militia, Ali Kanna has spent his time trying to unite local forces in a “Fezzan Army” that would acknowledge the legitimacy of the Qaddafist Jamahariya.60 In October 2016, there were reports that former Qaddafist officers had appointed Ali Kanna as the leader of the “Libyan Armed Forces in Southern Libya,” a structure apparently independent of both the GNA and Haftar’s LNA.61

The effort to promote armed Qaddafism in Fezzan has faltered under pressure from the LNA’s General Muhammad Bin Nayel.62 LNA spokesman Colonel Ahmad al-Mismari downplayed the threat posed by Ali Kanna, claiming his “pro-Qaddafi” southern army is composed mostly of foreign mercenaries with few professional military officers.63

In mid-October, an armed group of Qaddafists (allegedly including 120 members of the Darfuri JEM) attempted to take control of the major routes in and out of Tripoli before clashing with Islamist Abd al-Rauf’s Rada (Deterrence) force, a semi-autonomous police force operating nominally under the GNA’s Ministry of the Interior.64

Two alleged leaders of the Qaddafist group, Libyan Mabruk Juma Sultan Ahnish (aka Alwadi) and Sudanese Rifqa al-Sudani, were captured and detained by Rada forces.65 Ahnish is a member of the Magraha tribe from Brak al-Shatti, while Rifqa (aka Imam Daoud Muhammad al-Faki) is supposedly a Sudanese member of JEM, though other accounts claim he may be Libyan.66 According to Rada, the rest of the JEM group refused to surrender and presumably remains at large. It was claimed the Darfuri mercenaries were working on behalf of exiled Qaddafists belonging to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Libya (PFLL).67 i

The fragility of Tripoli’s water supply became apparent on October 19, 2017, when Mabruk Ahnish’s brother, Khalifa Ahnish, made good on his threat to turn off the Great Man-Made River if Mabruk was not released within 72 hours. Khalifa also threatened “kidnapping and murder,” cutting the Sabha-Tripoli road, and blowing up the southern gas pipeline leading to Italy via the Greenstream pipeline.68 Khalifa claimed to be working under the command of General Ali Kanna, though the general denied having anything to do with Khalifa or his brother.69

Conclusion

Haftar’s apparent military strategy is to secure the desert airbases south of Tripoli and insert LNA forces on the coast west of Tripoli, cornering his opponents in the capital and Misrata before mounting an air-supported offensive, similar to the tactics that enabled the capture of Jufra.j Haftar is trying to sell the conquest of Tripoli as a necessary (and desirable) step in ending illegal migration from Libyan ports to Europe.70 The strategy has political support; HoR Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thinni has consistently rejected international proposals for a mediated settlement to the Libyan crisis, insisting, as a former professional soldier, that only a military effort can unite the country.71

The LNA’s prolonged effort to take and secure Benghazi points to both the difficulty of urban warfare and the weakness of the LNA relative to its ambition to bring Libya’s largest cities under its control. The pullback of the PC/GNA-allied Misratan militias from Jufra may be preparation for a consolidated stand against Haftar, but it also weakens security in the south, offering room for new actors. Fezzan remains an attractive and long-term target for regional jihadis who may find opportunities to exploit or even hijack the direction of a protracted resistance in Fezzan to the imposition of rule by a new Libyan strongman. With no single group strong enough to resist Haftar’s LNA (whose ultimate victory is by no means certain), all kinds of anti-Haftar alliances are possible between Qaddafists, Islamists, Misratans, and even jihadis, with the added possibility of eventual foreign intervention by the West or Haftar’s assertive Middle Eastern or Russian partners.

In a study of the 2014-2016 fighting in ‘Ubari (a town in between Sabha and al-‘Uwaynat) released earlier this year, Rebecca Murray noted her Tuareg and Tubu sources “overwhelmingly dismissed the possibility that radical IS [Islamic State] ideology could take root in their communities, which they described as traditional, less religiously conservative, rooted in local culture, and loyal to strong tribal leaders.”72

The perspective of her sources might be optimistic. Unfortunately, the situation strongly resembles that which existed in northern Mali before well-armed Islamist extremists began moving in on existing smuggling networks, using the existence of “militarized, unemployed and marginalized youths” (as Murray describes their Libyan counterparts) to create new networks under their control while simultaneously undermining traditional community and religious leadership. While tribal leaders may still command a certain degree of loyalty, they are nonetheless unable to provide social services, employment, reliable security, or economic infrastructure to their communities, leaving them susceptible to those who claim they can, whether religious radicals or would-be strongmen. CTC

Dr. Andrew McGregor is the director of Aberfoyle International Security, a Toronto-based agency specializing in the analysis of security issues in Africa and the Islamic world.

Substantive Notes

[a] The BDB is a coalition of Islamists and former Qaddafi-era army officers, which includes some fighters who were in the now largely defunct Ansar al-Sharia group. See Andrew McGregor, “Libya’s Military Wild Card: The Benghazi Defense Brigades and the Massacre at Brak al-Shatti,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor 15:11 (2017).

[b] The town of al-‘Uwaynat in southwest Fezzan is not to be confused with Jabal ‘Uwaynat, a mountain in southeast Cyrenaïca. According to Malian and Mauritanian security sources, Belmokhtar was replaced in early May 2017 by his Algerian deputy, Abd al-Rahman al-Sanhaji, whose name suggests he is a Berber. Belmokhtar’s presence in southern Libya, far away from operations in Mali, was cited as a major reason for the change. Malek Bachir, “Exclusive: Notorious leader of Saharan al-Qaeda group loses power,” Middle East Eye, May 9, 2017.

[c] The ‘Ubari-based Maghawir Brigade, created from Sahelian Tuareg as a Libyan Army unit in 2004, split during the revolution with those favoring the revolution forming the new Ténéré (Tamasheq – “desert”) Brigade, while the Qaddafi loyalists were forced to flee to Mali and Niger. Many of the latter returned after the collapse of the Azawad rebellion in northern Mali (2012-2103) and regrouped around Tuareg General Ali Kanna Sulayman as the Tendé Brigade, though others rallied around Ag Ghali’s cousin, Ahmad Omar al-Ansari, in the Border Guards 315 Brigade. Mathieu Galtier, “Southern borders wide open,” Libya Herald, September 20, 2013; Rebecca Murray, “In a Southern Libya Oasis, a Proxy War Engulfs Two Tribes,” Vice News, June 7, 2015; Nicholas A. Heras, “New Salafist Commander Omar al-Ansari Emerges in Southwest Libya,” Jamestown Foundation Militant Leadership Monitor 5:12 (2014); Rebecca Murray “Southern Libya Destabilized: The Case of Ubari,” Small Arms Survey Briefing Paper, April 2017, fn. 23.

[d] The Islamic State declared the division of Libya into three provinces of its self-proclaimed caliphate on November 10, 2014, based on the pre-2007 administrative divisions of Libya: Wilayah Barqa (Cyrenaïca), Wilayah Tarabulus (Tripolitania), and Wilayah Fezzan. See Geoff D. Porter, “How Realistic Is Libya as an Islamic State ‘Fallback’?” CTC Sentinel 9:3 (2016).

[e] The Great Man-Made River is a Qaddafi-era water project that taps enormous aquifers under the Sahara to supply fresh-water to the cities of the Libyan coast. Cutting the pipelines is a relatively cheap and efficient way of applying pressure to the urban areas on the coast where most of the Libyan population lives.

[f] Military sources in the UAE claimed on October 23, 2017, that Qatar was assisting hundreds of defeated Islamic State fighters to leave Iraq and Syria for Fezzan, where they would create a new base to threaten the security of Europe, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. However, this alarming news must be tempered by recognition of the ongoing propaganda war being waged on Qatar by the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Amal Abdullah, “Hamdeen Organization moves hundreds of armed ‘Daesh’ to Libyan territory,” Al-Ittihad, October 22, 2017.

[g] The SG5 is a multilateral response to terrorism and other security issues in the Sahel region. Created in 2014 but only activated in February 2017, the SG5 consists of military and civil forces from Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad, and Burkina Faso, with logistical and financial assistance from France and other Western partners.

[h] The Italian government maintains that the estimated €5 million payment was issued only to the GNA government or Sabratha’s local council and not directly to a militia. However, the route payments took is largely irrelevant to the outcome. Patrick Wintour, “Italy’s Deal to Stem Flow of People from Libya in Danger of Collapse,” Guardian, October 3, 2017.

[i] The founding declaration of the PFLL declares its intent is to build a sovereign state and “liberate the country from the control of terrorist organizations that use religion as a cover and are funded by foreign agencies.” “Founding Declaration of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Libya,” Jamahiriya News Agency, December 25, 2016.

[j] Of concern to Tripoli are reports that Haftar forces have repeatedly struck civilian targets (especially in Hun) as displayed in the LNA’s Jufra air offensive. Abdullah Ben Ibrahim, “A night of airstrikes in Hun town,” Libya Observer, May 24, 2017.

Citations

[1] “Majority of Libya now under national army control, says Haftar,” Al Arabiya, October 14, 2017.

[2] “Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade controls Garabulli after three days of clashes,” Libyan Express, July 11, 2017; Waleed Abdullah, “Cautious calm east of Tripoli after clashes: Official,” Anadolu Agency, July 10, 2017; “Pro-Ghwell forces halt advance on Tripoli after Serraj calls for international allies to attack,” Libya Herald, July 7, 2017.

[3] “Former PC loyalist Majbri joins Gatrani and Aswad in fresh challenge to Serraj,” Libya Herald, September 3, 2017.

[4] Wolfram Lacher, “Libya’s Fractious South and Regional Instability,” Small Arms Survey Dispatch no. 3, February 2014.

[5] “Brigade 613 calls for response to Dignity Operation airstrikes in central Libya,” Libya Observer, May 23, 2017; “A night of airstrikes in Hun town,” Libya Observer, May 24, 2017; “Haftar’s warplanes conduct airstrikes on Al-Bunyan Al-Marsous locations in central Libya,” Libyan Express, May 24, 2017.

[6] “Haftar forces capture strategic Libya airbase after ‘secret deals,’” The New Arab, June 4, 2017; “Operation Dignity seizes Jufra airbase in central Libya,” Libyan Express, June 3, 2017; “Haftar’s forces seize Hun town in Jufra, a dozen killed,” Libyan Express, June 3, 2017; Jamie Prentis, “Waddan taken by LNA in fierce fighting,” Libya Herald, June 2, 2017; “Clashes in Waddan town leave a dozen killed,” Libya Observer, June 3, 2017.

[7] “LNA sets up new force in Bani Walid,” Libya Herald, October 19, 2017.

[8] Lamine Ghanmi, “ISIS regroups in Libya amid jihadist infighting,” Middle East Online, October 15, 2017.

[9] “Islamic State set up Libyan desert army after losing Sirte – prosecutor,” Reuters, September 28, 2017; “IS cameraman involved in 2015 Sirte massacre of Egyptian Christians in custody says Assour,” Libya Herald, September 28, 2017.

[10] “Sudanese Jihadist killed in eastern Libya,” Sudan Tribune, February 10, 2016; “Sudanese security releases three ISIS sympathizers,” Sudan Tribune, January 1, 2016.

[11] “Sudanese twin sisters arrested in Libya over ISIS connections,” Sudan Tribune, February 7, 2017.

[12] “9 Sudanese migrants found dead near Libyan border, 319 rescued: SAF,” Sudan Tribune, May 1, 2014; Andrew McGregor, “Jabal ‘Uwaynat: Mysterious Mountain Becomes a Three Border Security Flashpoint,” AIS Special Report, June 13, 2017.

[13] Aidan Lewis, “Islamic State shifts to Libya’s desert valleys after Sirte defeat,” Reuters, February 10, 2017; John Pearson, “Libya sees new threat from ISIL after defeat at Sirte,” National [Abu Dhabi], February 10, 2017.

[14] “IS slays two in ambush on Third Force convoy,” Libya Herald, May 8, 2017; “Libyan Rivals Rumored to Meet Again in Cairo This Week,” Geopoliticsalert.com, May 10, 2017.

[15] Ahmed Elumami, “Islamic State set up Libyan desert army after losing Sirte – prosecutor,” Reuters, September 28, 2017; “Libya Dismantles Network Involved in Beheading of Copts,” Al-Sharq al-Awsat, September 29, 2017.

[16] See Andrew McGregor, “Islamic State Announces Libyan Return with Slaughter of LNA Personnel in Jufra,” AIS Special Report, August 24, 2017.

[17] Hsain Ilahiane, Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen), 2nd ed., (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), pp. 146-147.

[18] Nick Turse, “The US Is Building a $100 Million Drone Base in Africa,” Intercept, September 29, 2016; “France: The Saharan Policeman,” BBC, March 19, 2015.

[19] “Chad shuts border with Libya, deploys troops amid security concerns,” Reuters, January 5, 2017.

[20] Lorenzo Cremonesi, “Migranti, Haftar: Vi aiutiamo a fermarli, dateci gli elicotteri,” Corriere della Sera, September 28, 2017.

[21] Lorenzo Cremonesi, “Haftar e le minacce alle navi italiane: ‘Senza il nostro accordo, è un’invasione,’” Corriere della Sera, August 11, 2017.

[22] Jamal Adel and Hadi Fornaji, “Massive rise in petrol prices in south, but convoys of tankers from Misrata expected to start rolling this weekend,” Libya Herald, September 23, 2017.

[23] Jamal Adel, “Qatrun Tebu brigade clamps down on southern border smuggling,” Libya Herald, September 11, 2017.

[24] “Southern border reported blockaded as Qatrun leader confirms ‘big’ drop in migrants coming from Niger,” Libya Herald, September 7, 2017.

[25] “Barka Shedemi crée la panique à Niamey et maitrise la frontière,” Tchad Convergence/Le Tchadanthropus-Tribune, October 23, 2017.

[26] Jamie Prentis, “Sudan reiterates support for Presidency Council but concerned about Darfuri rebels in Libya,” Libya Herald, May 1, 2017.

[27] “Hafter praises the PC and says Qatar is arming Libyan terrorists,” Libya Herald, May 30, 2017.

[28] “Libya Army Spokesman Says Qatar Involved in Number of Assassinations,” Asharq al-Awsat, June 8, 2017; “Libyan army reveals documents proving Qatar’s interference in Libya,” Al Arabiya, June 8, 2017; “Libyan diplomat reveals Qatari ‘involvement’ in attempt to kill General Haftar,” Al Arabiya, June 6, 2017; “Haftar accuses Qatar of supporting terrorism in Libya,” Al Arabiya, May 29, 2017.

[29] “Sudanese rebel group acknowledges fighting for Khalifa Haftar’s forces in Libya,” Libya Observer, October 10, 2016; “Intelligence Report: Darfur Mercenaries Pose Threat on Peace in the Region,” Sudan Media Center, May 22, 2017; “Darfur Groups Control Oilfields in Libya,” Global Media Services-Sudan, July 27, 2016.

[30] “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), S/2017/466,” June 1, 2017, p. 115; “Sudan: Rebel Commander Killed, Chief Captured in Darfur Battles,” Radio Dabanga, May 23, 2017; “Sudan, rebels resume heavy fighting in North Darfur,” Sudan Tribune, May 29, 2017.

[31] “East-based Libyan army says al-Qaeda attacked airbase,” Channel TV [Amman], May 22, 2017.

[32] Maha Elwatti, “LNA claims many Brak al-Shatti attackers were foreign, says it is fighting al-Qaeda,” Libya Herald, May 20, 2017.

[33] “Letter Dated 4 March 2016 from the Panel of Experts on Libya Established Pursuant to Resolution 1973 (2011), Addressed to the President of the Security Council,’” S/2016/209, United Nations Security Council, March 9, 2016; Rebecca Murray “Southern Libya Destabilized: The Case of Ubari,” Small Arms Survey Briefing Paper, April 2017, fn. 57.

[34] Lacher.

[35] “Libya militia to halt attack on Chadian fighters in south,” Facebook via BBC Monitoring, June 15, 2017; Célian Macé, “Mahamat Mahad Ali, la rose et le glaive,” Libération, May 29, 2017.

[36] “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), S/2017/466,” June 1, 2017, p. 18. See also Andrew McGregor, “Rebel or Mercenary? A Profile of Chad’s General Mahamat Mahdi Ali,” Jamestown Foundation Militant Leadership Monitor, September 2017.

[37] “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), S/2017/466,” June 1, 2017, p. 116.

[38] Beata Stur, “Germany, Italy propose EU patrols along Libya’s border with Niger,” New Europe, May 15, 2017; May 15, 2017; “Italy and Germany call for EU mission on Libyan border,” AFP, May 14, 2017.

[39] Paolo Mastrolilli, “A Plan for Carabinieri in Mosul After Caliph’s Militiamen Take Flight,” La Stampa [Turin], April 21, 2017.

[40] Sami Zaptia, “Libya refused international requests to strike migrant smuggling militias: GNA Foreign Minister Siala,” Libya Herald, April 29, 2017.

[41] Gabriel Harrison, “EU parliament head says Libya should be paid €6 billion to stop migrants,” Libya Herald, August 28, 2017.

[42] “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), S/2017/466,” June 1, 2017, p. 63.

[43] Jamie Prentis, “LNA airstrikes again hit Tamenhint and Jufra,” Libya Herald, April 29, 2017; “Deadly Clashes in Sebha over Car Robbery,” Libya Herald, May 5, 2017.

[44] Francesco Grignetti, “L’Italia studia una missione in Niger per controllare la frontiera con la Libia,” La Stampa [Turin], October 15, 2017.

[45] “Tebu, Tuareg and Awlad Suleiman make peace in Rome,” Libya Herald, March 30, 2017.

[46] Patrick Wintour, “Italian minister defends methods that led to 87% drop in migrants from Libya,” Guardian, September 7, 2017.

[47] “Salafists loyal to Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar control Sabratha, declare war on Tripoli,” Libyan Express, October 6, 2017; “Libya pro-GNA force drives rival out of Sabratha,” AFP, October 7, 2017.

[48] Abdullah Ben Ibrahim, “Khalifa Haftar: Libyan Army is launching legitimate war in Sabratha,” Libya Observer, October 3, 2017. See also Andrew McGregor, “Radical Loyalty and the Libyan Crisis: A Profile of Salafist Shaykh Rabi’ bin Hadi al-Madkhali,” Jamestown Foundation Militant Leadership Monitor, January 2017.

[49] “ISIS Fighting Operation Room declares victory in Sabratha,” Libya Observer, October 6, 2017.

[50] Francesca Mannocchi, “Guerra di milizie a Sabratha, ecco perché dalla città libica riparte il traffico dei migrant,” L’Espresso, September 19, 2017; Nello Scavo, “Tripoli. Accordo Italia-Libia, è giallo sui fondi per aiutare il Paese,” Avvenire, September 1, 2017.

[51] Khalid Mahmoud, “Libya: Serraj, Haftar Share the ‘Liberation’ of Sabratha,” Asharq al-Awsat, October 7, 2017.

[52] Cremonesi, “Migranti, Haftar: Vi aiutiamo a fermarli, dateci gli elicotteri;” “Salafists loyal to Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar control Sabratha, declare war on Tripoli.”

[53] “Saif al-Islam Gaddafi freed from Zintan, arrives in eastern Libya,” Libyan Express, June 10, 2017; Jamie Prentis, “ICC chief prosecutor demands handover of Saif Al-Islam,” Libya Herald, June 14, 2017.

[54] Chris Stephen, “Gaddafi son Saif al-Islam ‘freed after death sentence quashed,” Guardian, July 7, 2016; Raf Sanchez, “Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam at large in Libya after being released from death row, lawyer says,” Telegraph, July 7, 2016.

[55] AMN al-Masdar News, October 18, 2017.

[56] Marc Perelman, “Ghassan Salamé: le processus politique en Libye est ouvert ‘à tout le monde sans exception,’” France 24, September 23, 2017.

[57] Lacher. For General Kanna, see Andrew McGregor, “General Ali Kanna Sulayman and Libya’s Qaddafist Revival,” AIS Special Report, August 8, 2017.

[58] “Qaddafi’s air force chief flies home from exile: report,” Libya Herald, June 18, 2017.

[59] “Tajouri releases Qaddafi people imprisoned for six years,” Libya Herald, June 11, 2017.

[60] Mathieu Galtier, “Libya: Why the Gaddafi loyalists are back,” Middle East Eye, November 11, 2016; Vijay Prashad, “Don’t Look Now, But Gaddafi’s Political Movement could be Making a Comeback in Libya,” AlterNet.org, December 29, 2016; François de Labarre, “Libye, le general Ali Kana veut unifier les tribus du Sud,” Paris Match, May 22, 2016.

[61] Ken Hanly, “Southern army leaders try to change leaders unsuccessfully,” Digital Journal, October 9, 2016; Abdullah Ben Ibrahim, “Armed groups in southern Libya abandon Dignity Operation,” Libya Observer, October 9, 2016.

[62] Jamie Prentis, “LNA resumes airstrikes on Tamenhint as Misratans target Brak Al-Shatti: report,” Libya Herald, April 13, 2017.

[63] “’We are the LNA, we are everywhere in Libya’ says LNA spokesman,” Libya Herald, February 2017.

[64] “Tripoli-based Special Deterrent Force apprehends Gaddafi-loyal armed group,” Libya Observer, October 16, 2017.

[65] “Libya on brink of water crisis as armed group closes main source,” Libyan Express, October 23, 2017; “Water stops in Tripoli as Qaddafi militants now threaten to blow up gas pipeline,” Libya Herald, October 19, 2017.

[66] Hadi Fornaji, “Now Tripoli port as well as Mitiga airport closed as Ghararat fighting continues,” Libya Herald, October 17, 2017.

[67] “Tripoli-based Special Deterrent Force apprehends Gaddafi-loyal armed group;” “Rada says it has broken up Tripoli attack plot,” Libya Herald, October 16, 2017.

[68] “Gunmen block Tripoli-Sebha road in new bid to force release of Mabrouk Ahnish,” Libya Herald, October 23, 2017.

[69] “Armed Group Threatens to Blow Up Pipeline that Transmits Libya’s Gas to Italy,” Asharq al-Awsat, October 19, 2017; “Gaddafis threaten Tripoli residents with water cut,” Libya Observer, October 17, 2017; “Water stops in Tripoli as Qaddafi militants now threaten to blow up gas pipeline.”

[70] “Eastern forces already devised plan to control Tripoli, says spokesman,” Libyan Express, July 11, 2017.

[71] Hadi Fornaji, “Thinni spurns calls for political dialogue, says ‘military solution’ is only answer to Libya crisis,” Libya Herald, April 8, 2017.

[72] Rebecca Murray, “Southern Libya Destabilized: The Case of Ubari,” Small Arms Survey Briefing Paper, April 2017.