Eurasia Daily Monitor Vol. 22, Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC.

Andrew McGregor

May 28, 2025

Executive Summary:

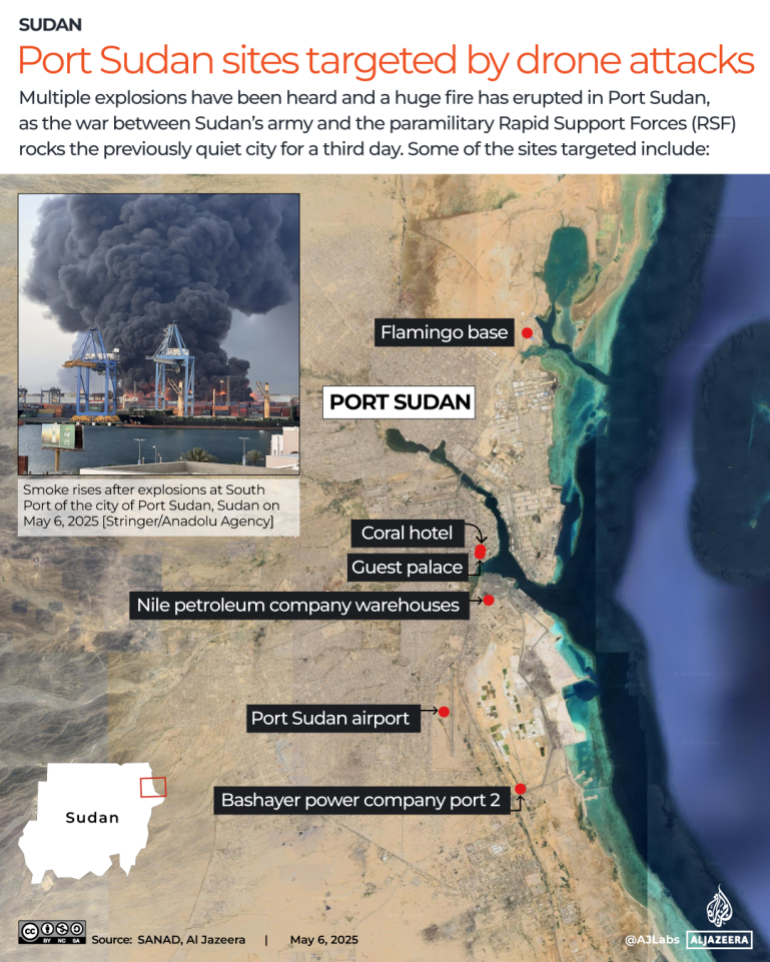

- Russia’s plans to create a naval base on the Sudanese coast of the Red Sea have been upset by drone attacks launched on Port Sudan in early May. Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces claimed responsibility for the attack.

- The destruction of Port Sudan’s infrastructure demonstrates that Sudan’s domestic instability would threaten a Russian base, potentially jeopardizing a broader arms-for-access agreement that included Sudan’s acquisition of Russian warplanes.

- Sudan accused the United Arab Emirates (UAE) of supplying the People’s Republic of China (PRC)-made drones used in the attack. The UAE and the PRC may be acting to curb Russia’s naval ambitions.

Fuel depot in Port Sudan burns after drone attack, May 5, 2025 (Xinhua).

Fuel depot in Port Sudan burns after drone attack, May 5, 2025 (Xinhua).

Russia’s hope of establishing a naval base along Sudan’s Red Sea coast took a serious blow when drones shattered infrastructure at its proposed site from May 4 to 8 (Sudan Tribune, May 7, 9). The week-long drone attack, believed to have been carried out by Sudan’s rebel paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), exposed the vulnerability of the port’s proposed site to damage related to domestic instability. The alleged involvement of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as the supplier of the RSF’s People’s Republic of China (PRC)-made drones complicates the international implications of the devastating attack.

General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, May 6, 2025 (Sudan Tribune)

General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, May 6, 2025 (Sudan Tribune)

Following the destruction of the Khartoum/Omdurman capital region and its industrial base early in Sudan’s civil war in 2023, Port Sudan has acted as the political and military headquarters of the Sudanese state. Port Sudan operates under the unelected Transitional Sovereignty Council (TSC) and its dominant partner, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), commanded by General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan. Both the RSF and the UAE reject what they refer to as “the Port Sudan Authority” as the legitimate government of Sudan (Mada Masr, May 9). The city hosts Sudan’s most important port, its last functioning civil airport, a naval base, and a military airport. Crude oil from Sudan and South Sudan is exported from Port Sudan, and refined petroleum products for domestic use are stored there. It is the only delivery point for desperately needed aid and relief supplies in the war-ravaged nation.

Smoke billowed from the Sudanese Navy’s base at Flamingo Bay, 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) north of Port Sudan’s commercial port, after being struck by drones for five successive days in early May (Sudan Tribune, May 7, 9). Satellite imagery published by Russian site Insider.ru revealed what appeared to be large-scale destruction at the base (Insider.ru, May 13). Flamingo Bay is the proposed site for the new Russian naval base (AIS, March 24, 2022; see EDM, July 8, 2024, March 6, April 30; New Arab, May 8).

Flamingo Bay naval facility, north of Port Sudan (GoogleEarth)

Flamingo Bay naval facility, north of Port Sudan (GoogleEarth)

The destruction of oil depots at Port Sudan has created immediate fuel shortages and rising prices in government-held territory. The port is suffering from shortages of food and clean water, blackouts, and looting by desperate citizens (Radio Dabanga, May 8). Thousands have fled the city as civil authorities warn of an environmental and health disaster (Sudan Tribune, May 6; Mada Masr, May 9). Drones also struck radar installations, warehouses, and munitions stores at Osman Digna Air Base in Port Sudan, causing a series of explosions (Sudan TV, May 5). The strikes halted civilian air traffic, including humanitarian aid flights, by causing heavy damage at the adjacent Port Sudan International Airport (Sudan Tribune, May 7; Radio Dabanga, May 8). Other targets included General al-Burhan’s residence and the Marina Hotel, which often houses foreign diplomats (Mada Masr, May 9). Swarms of drones struck the historic Red Sea port of Suakin, some 50 kilometers (31 miles) south of Port Sudan, and the eastern city of Kassala on May 4 to 6 (Xinhua, May 6). Qatar, the UAE’s regional rival, is redeveloping Suakin in a $4 billion project.

Osman Digna military airport in flames, May 4, 2025

Osman Digna military airport in flames, May 4, 2025

As the attacks continued, Moscow expressed “deep concern over the ongoing bloody armed confrontation” in Sudan (TASS, May 5). Despite three years of Russian attacks on civilian targets and infrastructure in Ukraine, the Kremlin statement added that “Russia believes that carrying out attacks on civilian infrastructure is unacceptable” (TASS, May 5). The Russian embassy in Sudan reported operations at its temporary embassy in Port Sudan were unaffected by the bombing, saying that “the situation is tense, naturally, but not critical” (RIA Novosti, May 6).

Other than drones, the RSF does not have aerial assets or personnel operating closer to Port Sudan than Omdurman, 670 kilometers (416 miles) away. The attack’s precise targeting suggests that the RSF obtained or was given accurate coordinates by means normally unavailable to the technologically weak paramilitary. The operational range of the PRC-made Sunflower-200 one-way attack drones, which military analysts believe the RSF used, is 1,500 to 2,000 kilometers (932 to 1,242 miles), with a 30- to 40-kilogram payload (Defense Express, May 6; Cobtec International, accessed May 21). The UAE obtained the Sunflower-200 in January 2024 (Janes, January 25, 2024).

The commander of the Red Sea military region and the Sudanese Navy, Lieutenant General Mahjub Bushra, claimed that drones were launched from UAE military facilities at Berbera in Somaliland and Bosaso in Puntland (Sudan TV, May 5). Puntland’s Minister of Information, Mahmoud Aydid Dirir, described the accusation that the UAE operated missiles from Bosaso as part of “a broader effort to undermine Puntland’s reputation and its ongoing fight against terrorism” (Mogadishu24, May 8).

SAF intelligence presented another scenario, suggesting the drones may have entered RSF-controlled regions of Sudan via the Libyan desert, past remote Jabal ‘Uwaynat (where Libya, Sudan, and Egypt meet) and into Darfur to be distributed to strategic launch points further east (AIS, June 13, 2017; France24.com, April 19; Mada Masr, May 9). Another possible route for the RSF to obtain the drones would be through the Amdjarass airstrip in Chad, close to RSF-held territory in Sudan. UAE transport aircraft make regular trips to Amdjarass. Many of the flights are believed to be delivering arms, though the UAE claims they deliver only humanitarian supplies (Reuters, December 12, 2024; Africa Defense Forum, January 7).

Sudan cut off diplomatic relations with Abu Dhabi on May 6 because of their alleged involvement in the attacks, denouncing it for “state terrorism” while threatening retaliation (Middle East Eye; Sudan Tribune, May 8; Mada Masr, May 9). RSF sources confirmed the paramilitary’s responsibility for the strikes on Port Sudan, Kassala, and oil depots in Kosti (White Nile Province) as part of a plan to take the war to Port Sudan and the relatively untouched north of Sudan (Mada Masr, May 9).

An indefinite delay in the construction of a Russian naval facility at Port Sudan due to the attacks will likely jeopardize the Sudanese state’s planned acquisition of Russian warplanes, such as the Su-30 and Su-35, in exchange for the use of the port. The potential loss of Russian interest in Sudan could work in the PRC’s interest. Even though PRC-made drones caused the damage to Port Sudan, the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF) has only blamed the intermediary supplier, the UAE. If Russia backs off from the port deal and its reciprocal arms supplies, Beijing may be able to step in to make arrangements with the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF).

An indefinite delay in the construction of a Russian naval facility at Port Sudan due to the attacks will likely jeopardize the Sudanese state’s planned acquisition of Russian warplanes, such as the Su-30 and Su-35, in exchange for the use of the port. The potential loss of Russian interest in Sudan could work in the PRC’s interest. Even though PRC-made drones caused the damage to Port Sudan, the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF) has only blamed the intermediary supplier, the UAE. If Russia backs off from the port deal and its reciprocal arms supplies, Beijing may be able to step in to make arrangements with the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF).

The PRC is obliged, as a signatory to the United Nations’ Arms Trade Treaty, to prevent the UAE from selling PRC arms to a banned entity such as the RSF. It seems improbable that the PRC is unaware of how the UAE disposes of its hi-tech military imports. This raises the question of whether the UAE is mediating the transfer of PRC drones through established supply networks to the RSF to deter the expansion of Russian influence and facilities in Africa. The PRC has its own ambitions in Africa, as well as a naval base in Djibouti at the southern entrance to the Red Sea.

It is uncertain whether Russia has supplied Sudan with advanced air defense systems. Sudanese Major General Mutasim ‘Abd al-Qadir indicated that Russia has discretely supplied defense systems, while Sudanese intelligence sources indicate that Sudan turned down a Russian offer to deploy a S-400 air defense system at Port Sudan due to fears of negative U.S. and European reactions (Mada Masr, May 9; Insider.ru, May 13). Advanced air defense systems would be essential for the existence of a Russian base at Port Sudan, but would also raise issues regarding the touchy issue of Sudanese sovereignty.

The UAE has taken advantage of Russian naval base troubles. After the post-Assad government of Syria canceled 2019’s 49-year agreement with Russia’s Stroynasgas to manage the port of Tartus, the UAE’s DP World signed a memorandum of agreement to take over management of the port on May 16 with a projected $800 million investment (TASS, January 21; SANA, May 16). The Russian facility at Port Sudan was intended in part to replace the loss of Tartus. As the feasibility of establishing a Russian base in the Red Sea begins to diminish under the weight of domestic insecurity and foreign intervention, Moscow may intensify discussions to create an alternative naval base at the Libyan port of Tobruk.